Lamium album, the white dead-nettle, is a perennial flowering plant in the fragrant family Lamiaceae or Labiatae that includes many of our best known of culinary herbs, such as mints (Mentha), lavender (Lavandula), basil (Ocimum), sage (Salvia), rosemary (Rosmarinum) and thyme (Thymus) (but sadly not parsley) . It’s not really a nettle – they are members of another family entirely – but dead-nettles have some features that can be mistaken for them. They have white flowers, are softly hairy and they don’t sting.

Apart from white dead-nettle, other common names in use for this plant include archangel, white archangel (Blamey, Fitter & Fitter, 2013), helmet flower, Adam and Eve (Plantlife), bee nettle (RHS), blind nettle (RHS), and dumb nettle.

Lamium is the type genus of the Lamiaceae , the name derived from Greek laimos, meaning throat, alluding to the shape of the flowers. Lamium album is a Linnean species, first published by Carl Linnaeus in Sp. Pl.: 579 (1753).

The Lamiaceae are characterized by having square stems with opposite and decussate leaves without stipules, usually hairy with simple and glandular hairs that secrete fragrant oils. The family even includes some tree species, notably the tropical Asian genus Tectona, commonly known as teaks, now cultivated in tropical plantations world-wide. Recently the Valerianaceae have been merged with the Lamiaceae by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group on the basis of new molecular evidence.

Description

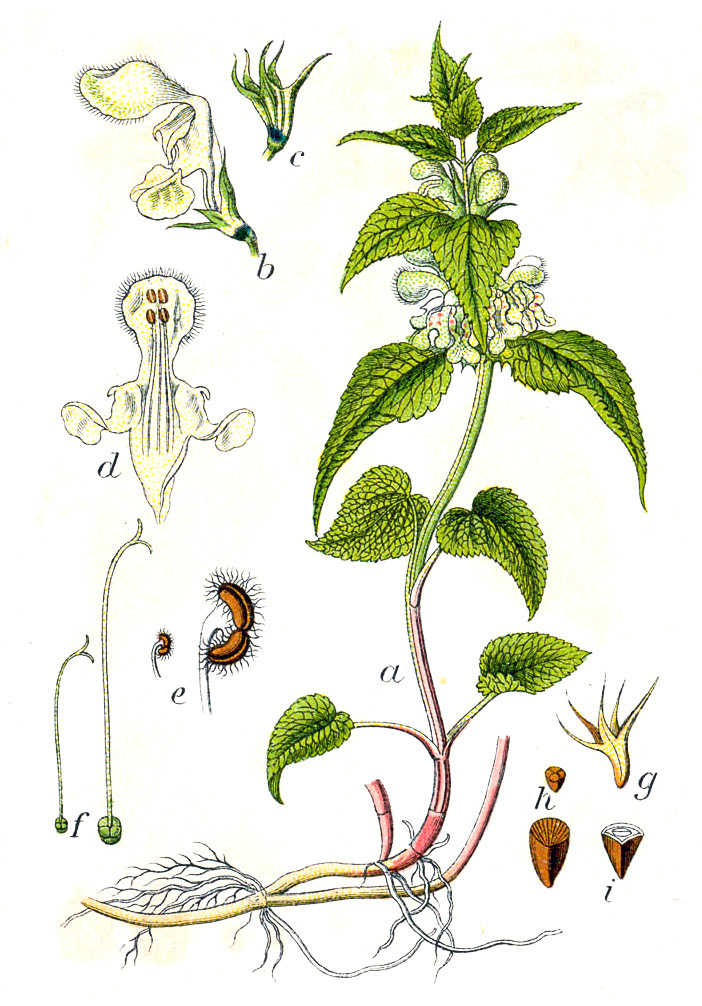

The white dead-nettle is a herbaceous perennial, unlike its common annual relative, the red dead-nettle, L. purpureum. It reproduces both sexually by seed and vegetatively by rhizomes and stolons, giving rise to clonal patches. The flowering stems arise from prostrate rhizomes or stolons, from which upright foliage and flowering shoots arise, rarely standing taller than 30-50cm. They are sharply square in cross section (see image below) The leaves are long-stalked, (petiolate), approximately heart-shaped (cordate), coarsely-toothed, hairy all over and can look very like nettle leaves (see https://botsocscot.wordpress.com/2020/07/05/plant-family-of-the-week-6th-july-2020-urticaceae-the-nettles/ ), but they have no stinging hairs, hence the common names dead-nettle, deaf nettle or dumb-nettle.

Despite the common name, dead-nettles are not closely related to stinging nettles and are most easily distinguished from them by their flowers, which are large, conspicuous and bisexual, by contrast with the tiny greenish, unisexual flowers of nettles. Dead-nettle flowers are bilaterally symmetrical or zygomorphic, well adapted for insect-pollination because they have evolved to fit the bilateral symmetry and general shape of insect visitors (Proctor & Yeo, 1973).

The white or faintly greenish flowers of Lamium album have a long, straight corolla tube, leading to a reward of nectar with about 40% sugar, but there is a constriction near the base covered with stiff hairs that prevents small insects from reaching the nectar. Medium- sized bees with short tongues, and even bumblebees, may rob the nectar by biting through the tube to reach the nectar directly from the outside (Willmer 1980).

Unlike the pea family, which has flowers of a similar general shape in which pollen is transferred to the underside of the insect, dead-nettles, in common with orchids, transfer pollen to the upper parts of the head or thorax of a pollinating insect. A hooded upper lip arches high over the style with its bifurcated stigma and the four stamens, two long and two short, that are shaped to follow its curve. The style and the staminal filaments lie closely parallel in a flat bundle.

The lower lip of the corolla forms an insect landing strip, divided into two lobes with 1-3 shallow teeth on each, although these are not always conspicuous. A feature that usually goes unremarked and is rarely illustrated is that when the flower is viewed face-on there is a dull, ochre-coloured Y-shaped marking at the top of the lower lip as it enters the mouth of the flower, and two ochre spots on each side of the mouth. On closer inspection, the Y is more nearly an M, the arms recurving out of sight within the throat of the flower to re-appear each side as the lower lateral spot. Although the marks are inconspicuous, to the uv/blue vision of bees they would appear dark, nearly black, and provide effective marking of the entrance to the flower.

All photographs ©Chris Jeffree

The flowers are arranged in whorls of approximately 6 to 15 at each of the upper nodes, just above the insertion of the leaves, in an arrangement known as a verticillaster.

Lamium album is hairy on almost all surfaces, including the calyx, the outer parts of the corolla, the staminal filaments and the anthers, but although it does have some glandular hairs, these produce little or no conspicuous scent that can be detected by humans. The majority of the hairs are simple tapering trichomes.

The four stamens and the style lie side by side in one plane in the hood of the flower. The black and gold anthers are fancifully likened to two human figures, Adam and Eve, hence one of the common names of the plant. An alternative interpretation attributed to Enid Blyton (I wonder if there is an even earlier history), is they look like tiny fairy dancing shoes. In a ‘A Fairy Secret’ from her Good Morning Book, she tells that fairies hide their dancing shoes in the flowers of the white dead-nettle. And here is the proof:

Distribution

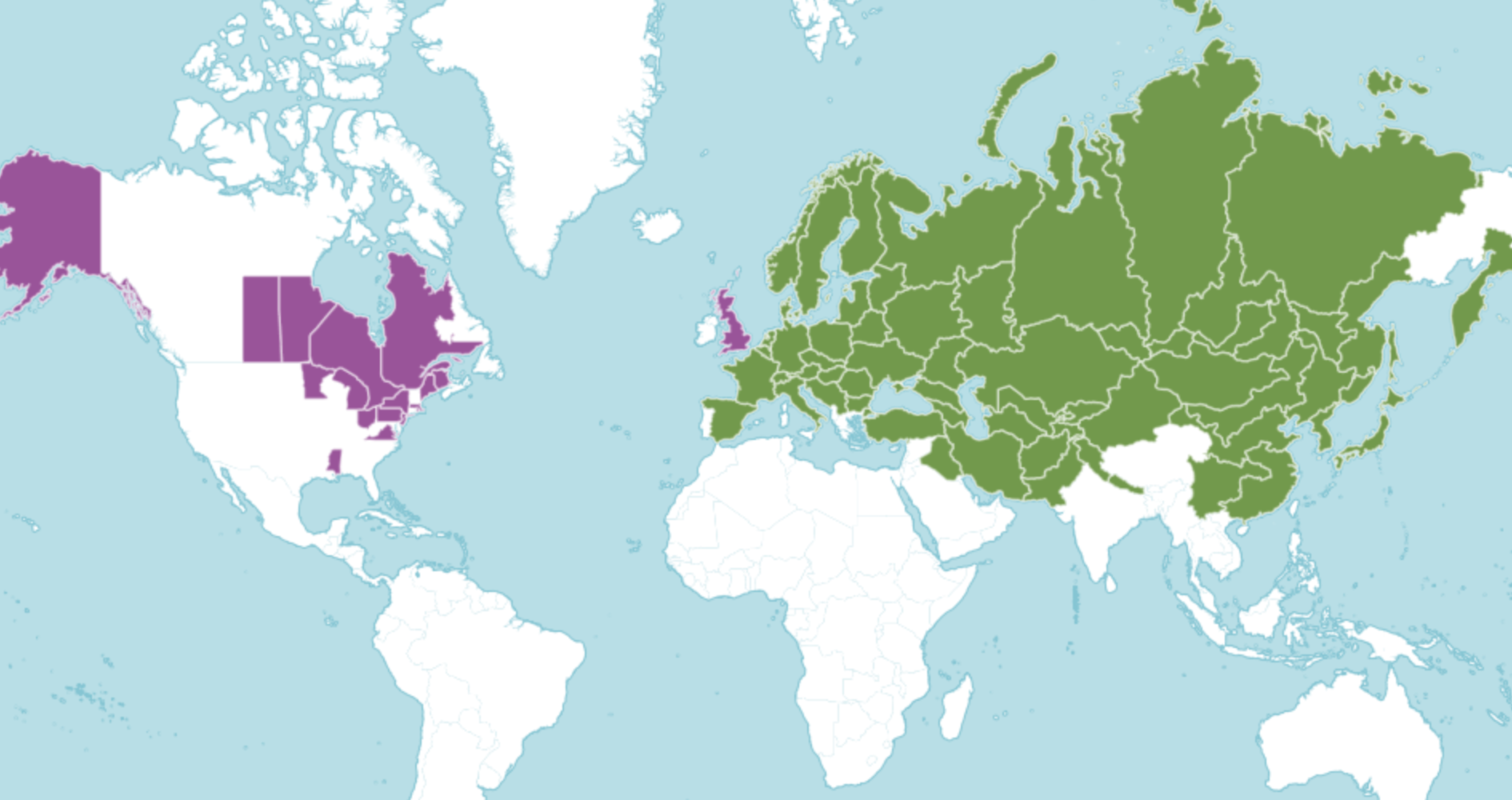

Lamiums, the dead-nettles, are native to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa, but many of the species have been distributed in the course of trade to other parts of the world where climates are temperate. Britain is one of those regions, originally outside its native range, into which the species was introduced so long ago that the precise date and manner of its introduction are lost in the mists of time. Lamium album is therefore described as an archaeophyte, but also by Stace (2019) as archaeophyte-denizen, meaning that it is very successfully naturalized, and can compete with established vegetation, behaving more or less as if it were native.

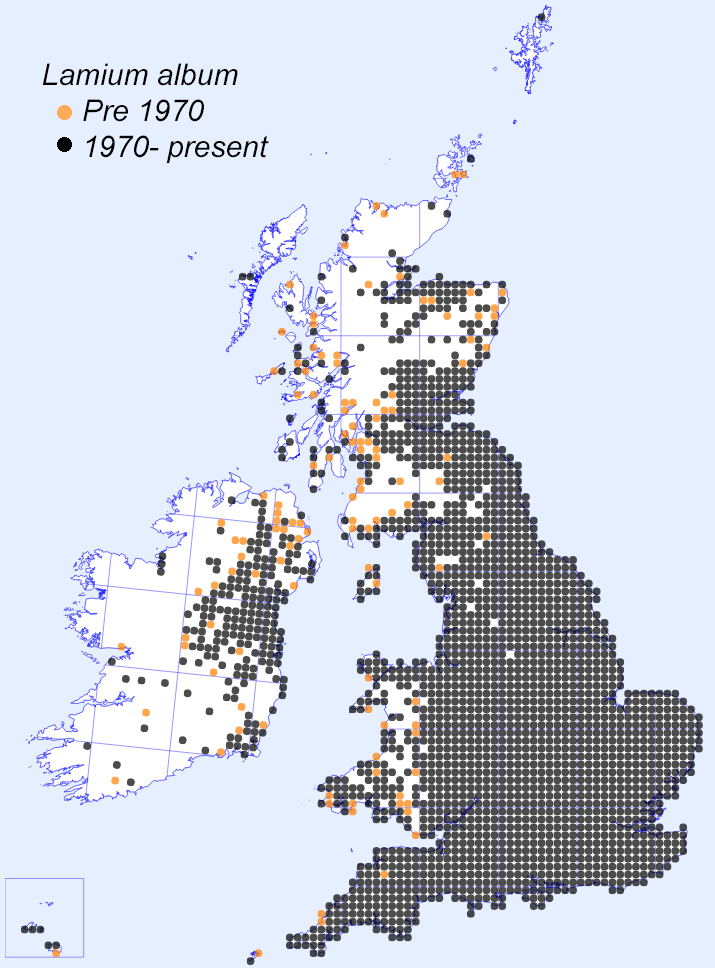

Its distribution in Britain is southern and eastern, common in most parts of England but avoiding the extreme west and north of Scotland and less common in Wales. In Ireland it occurs mainly in the east, and is rare in the south and west. Although its range is little changed since the BSBI Plant Atlas of 1962 (Perring and Walters, 1962), it appears to have retracted a little from earlier stations in the north and west of Great Britain (orange spots on the map below). It occurs as a weed in gardens, in agricultural field margins, stream and river banks, roadsides and in association with walls and old buildings.

Left, the distribution of Lamium album in the British Isles pre-1970 (orange) and post-1970 (black) (© BSBI) and world distribution (Right, © Plants of the World Online. Native range green, introduced range purple)

Phenology

When is it in flower? Easier to say when it is not. The flowering period is usually quoted as May to December, the flowering peak in midsummer, but this behaviour may be increasingly out of date as climate warms. Fitter and Fitter (2002) noted that plants can be found in flower throughout the winter. However, that can hardly be described as a modern trend since Bentham and Hooker (1930) state “Fl. The whole season”. At all events, today it is often among the top ten most frequent flowering plants recorded by the BSBI New Year Plant Hunt (https://nyph.bsbi.org/results.php) as shown below in the image below, taken two days before New Year 2022 in East Lothian and nationally this year it ranks at number 5, just ahead of red dead-nettle and shepherd’s purse.

Lamium album establishes well in fertile ground that is occasionally disturbed, providing scope for the establishment of seedlings. It is a perennial, so once established in gardens it will persist, gradually spreading by rhizomes (non photosynthetic underground stems) or stolons (lax photosythesising above-ground stems that root at the nodes) to form large clonal patches.

Uses and biodiversity services

Lamium album has a variety of culinary and medicinal uses. Since it continues to produce fresh green shoots throughout the winter, it has been cultivated as a winter-green vegetable. Both the flowers and young leaves are edible, and may be eaten either fresh in salads or cooked. It has clearly been of value to man for millennia. Connolly (1994) notes that it appears in association with castles and abbeys in Wales together with other medicinal plants such as greater celandine (Chelidonium majus) more often than would be expected by chance, and that it may have been imported into Britain deliberately, perhaps even by the Romans. According to Wren (1907), medicinal uses have been as an astringent, antihaemorrhagic or haemostatic, for menorrhagia and for other purposes, in many ways as for stinging nettles, but presumably without the associated discomfort.

The flowers are pollinated by heavy, long tongued bees such as bumble bees and mason bees that can open the flower and reach down the long corolla tube to the nectar. If the corolla is removed, a small drop of nectar can be sucked from its base that has a just-detectable scent that may be more valuable as an insect attractant than it is to us. The nectar and pollen are valuable resources of sugars and protein to bumblebees during the early season months when the brood is developing (Fussell & Corbet, 1991). However, whether the same can be said for honeybees is not clear.

In common with the stinging nettles, it is said to be the food plant of the garden tiger and angle shades (Phlogophora meticulosa) and burnished brass (Diachrysia chrysitis) moths, and either they (or possibly the observers) have a hard time distinguishing the two.

References

Bentham G. and Hooker J.D. (1930) Handbook of the British Flora. A description of the flowering plants and ferns indigenous to, or naturalised in the British Isles. L. Reeve and Co. Ltd., Ashford Kent.

Blamey, M., Fitter, R. & Fitter, A (2003). Wild flowers of Britain and Ireland: The complete guide to the British and Irish flora. A & C Black, London. ISBN 978-1408179505.

Connolly, A. (1994) Castles and abbeys in Wales: refugia for ‘mediaeval’ medicinal plants, Botanical Journal of Scotland, 46:4, 628-636, doi: 10.1080/13594869409441774

Fitter, H. & Fitter, R. S. R. (2002) Rapid changes in flowering time in British plants. Science 296, 1689-1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1071617

Fussell, M. & Corbet, S. A. (1991) Forage for bumble bees and honey bees in farmland: a case study, Journal of Apicultural Research, 30:2, 87-97, doi: 10.1080/00218839.1991.11101239

Stace, C. A. (2019). New flora of the British Isles (Fourth edition). C & M Floristics, Middlewood Green, Suffolk, U.K. ISBN 978-1-5272-2630-2.

Perring, F.H. and Walters, S.M. (1962) Atlas of the British Flora. Botanical Society of the British Isles. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd.

Proctor, M.C.F. and Yeo, P.F. (1973) The pollination of flowers. New Naturalist Series No 54, Collins & Co., London. ISBN 0 00 219504 6.

Willmer, P.G. (1980) The effects of insect visitors on nectar constituents in temperate plants. Oecologia 47, 270–277 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00346832

Wren, R.C. (1907) Potter’s new cyclopedia of botanical drugs and preparations. Daniel, Saffron Walden. ISBN 0 85297 197 3

© Chris Jeffree, January 2022

Stunning photographs. Despite having seen plant this almost every day of my life I never noticed the nectar guides.

LikeLike

Excellent description and superb pictures

LikeLike