ArtSeen

Marking Resilience: Indigenous North American Prints

On View

Museum of Fine Arts BostonNovember 4, 2023–March 17, 2024

Marking Resilience: Indigenous North American Prints is the first of two temporary exhibitions planned by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston to showcase recent acquisitions of prints by Indigenous artists of the United States and Canada. Organized by Marina Tyquiengco, Ellyn McColgan Assistant Curator of Native American Art and Edward Saywell, Chair, Prints and Drawings, with consulting co-curator, artist, and Rhode Island School of Design professor Duane Slick (Meskwaki/Ho-Chunk Nation), the show spotlights Indigenous resistance and “survivance” through printmaking. Though the exhibition itself is modest in scale—a single gallery containing some thirty works by thirteen artists—the objects’ collection and display represent a growing phenomenon in the contemporary art world: at institutions in the United States and beyond, works by Indigenous North American artists are finding greater visibility on gallery walls and exhibition schedules. Over the last year, audiences have had the opportunity to view major exhibitions of contemporary Indigenous North American art at such institutions as the National Gallery of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Bard College’s Hessel Museum of Art. In April, the Baltimore Museum of Art will embark upon a ten-month series of exhibitions and events devoted to Indigenous artists, while a sprawling sale show of contemporary Native American art opened at the storied Phillips Auction House in early January. As a writer for Penta put it in the headline of her coverage of that exhibition, “Contemporary Native American Art is Hot.”

Within the field of contemporary Indigenous North American art, certain names are appearing with particular frequency. Several of these figure in the MFA show: Marie Watt (Seneca Nation and German-Scottish ancestry), whose exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh opens in April; Jaune-Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes), the subject of a 2023 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art and curator of the exhibition The Land Carries Our Ancestors at the National Gallery of Art; Dyani White Hawk (Sičangu Lakota), a member of the 2023 class of MacArthur “Genius” Fellows; and Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw/Cherokee), who will represent the United States at the 2024 Venice Biennale (and who was a member of the 2019 class of MacArthur Fellows). These artists’ works often appear side-by-side in group shows, suggesting the emergence of a kind of “movement” or “school.” Following remarks by art historian Robert Bailey, I will refer to this tendency as “Indigenous Conceptualism.”

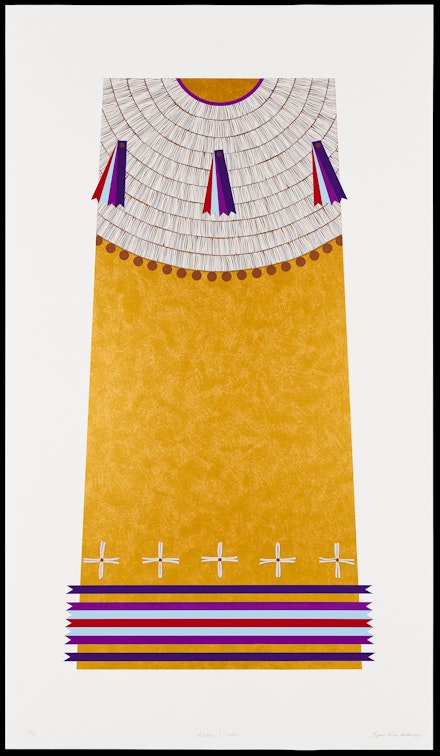

Among the shared concerns of the Indigenous Conceptualists—and this is one of the reasons why I think the moniker has merit—is a deep preoccupation with language. Like the structuralism-infused conceptualism of the 1960s and 1970s, works by the above artists and others in Marking Resilience are committed to a larger inquiry into systems of signification: the ways in which the spoken and written word, the drawing and the photograph, shape and fall short of our reality. Smith’s accordion-fold lithographed artist’s book All of My Relations Book I (2022), spread in a vitrine, juxtaposes written English text with images based on pictographs and petroglyphs used by Indigenous peoples of New Mexico. Watt’s print (photogravure, direct gravure, soft-ground etching, chine collé) A Spoon Is (2022) centers a silver spoon from the Buffalo History Museum purportedly made from melted silver coins given to a Seneca family in exchange for land at the time of one of the Treaties of Buffalo Creek. Maze-like text encircling the object declares it by turns “a method of conveyance,” “a witness,” “a shovel,” and “a complicated object,” eventually informing viewers of the Seneca terms for “big spoon” and “spoon, ladle” (“adógwa’ šowanëh” and “adógwa’ shä’,” respectively). White Hawk’s four showstopping screenprints, whose simulated dentalium shell collars and vast expanses of blue, yellow, green, and red reference the dresses of Plains women, also foreground Indigenous language; the artist gives each of the monumental prints both a Lakota and an English name. We are told in the label that the red print (Wačháŋtognaka⎥ Nurture, 2019) pays tribute to her mother, who was removed from her community as a child under policies of forced assimilation. Language is among the most enduring casualties of such policies, and one of the areas in which Indigenous activists are working hardest to reverse their effects.

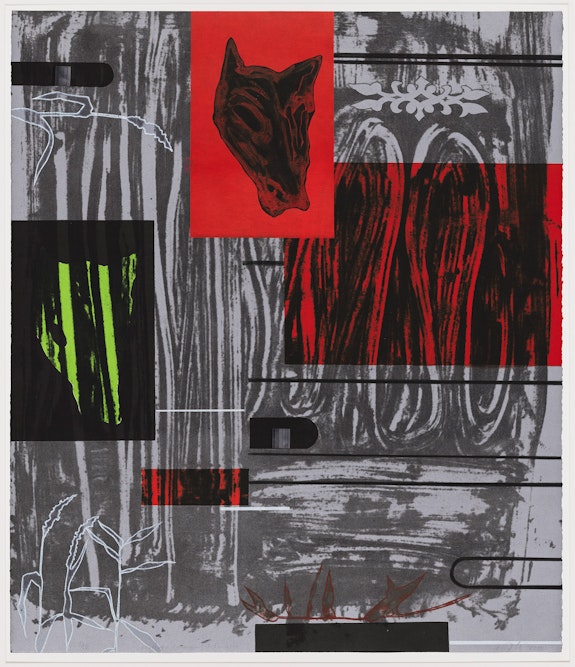

Gibson’s lithograph evokes another front in the long-waged war on Indigenous cultures. The words “hallelujah,” “SAY A PRAYER,” and “FIRE,” appearing against geometric patterns based on Native American parfleche rawhide boxes, suggest the Christian religion imposed on Indigenous peoples through boarding schools and the criminalization of Native American religious ritual. We are told that Gibson created Say a Prayer (2021) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and George Floyd protests of 2020. Gibson’s print joins others by Julie Buffalohead (Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma) and co-curator Slick in taking on a pandemic that, in early 2021, was in the process of killing almost twice as many Native Americans as other demographics. The devastation of Native American communities since 2020 echoes that visited on their ancestors through malaria and smallpox—by both accident and design—in the wake of colonization.

It is in relation to such historical injustices that the prints gathered at the MFA embody the notion of resilience. Working on paper, as the organizers point out, reclaims a material that previously served as a vehicle for the written laws and treaties (and maps, as Tatiana Reinoza has argued) that subjugated Indigenous peoples. For an exhibition of prints, the show offers precious little information to visitors about the mechanics of this paper-based work. We are not told much about specific printmaking techniques, presses where individual prints were executed, and so on. And although such details would be welcome to those of us who like to obsess over technique, I mention their absence less as a criticism than as evidence of the layered complexity of the work. Technically impressive as the prints may be, their true value lies in the conversations about narrative and culture and death that their creators are forcing to the center of the art world. We should get comfortable—the Indigenous Conceptualists aren’t going anywhere.