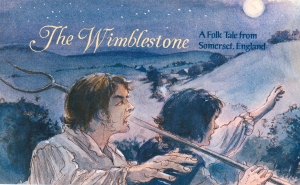

THE WIMBLESTONE

A retold folktale from Somerset, England

by

Claudia Riiff Finseth

Illustrated in Cricket Magazine by Gavin Rowe

The full, white orb of a moon hung like a lantern, lighting the lane for Gabriel and Zebedee Fry as the twin brothers walked home from the haymaking late on Midsummer’s Eve. They could see the Shipham farms around them, and smell the sweet fragrance of dewy hay and wild roses. The chorus of a thousand frogs shrilled along the streambeds that ribboned between the surrounding Somerset hills.

“Did ye hear those travelers at the inn talkin’ about Salisbury t’other night?” Zebedee, the bigger of the twins, sighed and shifted his hay fork to the other shoulder. “Great markets and a church steeple that touches the clouds. Such a town I’m dyin’ to see. Don’t ye never grow restless for excitement, Gabe?”

Gabriel, a slender youth, shook his head. “Nay. Too many people for my way o’ thinkin’. I’m content in Shipham.”

Zeb sighed again. “I’m tired o’ farmin’. If I only had tuppence, I’d be off to travel the world!”

They rounded a bend in the lane and came in view of Wimblestone Hill, a sweeping, grassy mound that was all hayfield but for one huge stone. For as long as anyone could remember, the field had been crowned with the gigantic stone, round and gray and smooth. Locals called it the Wimblestone.

The Fry twins passed Wimblestone Hill often, and always with the same ritual: they looked for the stone, as if to check on it and make sure it stood its place.

This night, it didn’t.

Gabriel grabbed Zeb, and they stared, jaws gaping and hearts throbbing, at the apparition before them.

Shining in the moonlight, the Wimblestone danced. Softly and slowly, as if to an unheard fiddler or piper, it leapt back and forth, rocking from side to side as if on two great stumped invisible legs. And each time it leapt, a heap of gleaming gold shone beneath it.

“Gold!” Zeb exclaimed.

Gabriel could only mumble, “What bewitchment—”

Yet how nimbly the Wimblestone danced, like a great, jolly fat man kicking up his heels. Great, indeed! The stone was bigger than a hay cart. Yet for all its bulk, the Wimblestone danced as if weight were no matter. It danced with nary a thud nor a bump. No quaking of the ground could be felt. And no matter where the stone leapt as it danced over the field, there beneath it was the gold, twinkling like a heap of yellow stars. Gabriel saw Zeb eyeing it.

About that time, the Wimblestone rustled along the far hedge and danced right down out of its field, into the old oak forest beyond.

A Derreenataggart Stone

A Derreenataggart Stone

“We can’t let that gold get away!” Zeb tore through the lane hedge and followed the stone.

“That’s madness!” Gabriel cried. But Zeb was gone, charging across Wimblestone field. Gabriel ran after him. Frogs and all were silent now. “At least there’s light—” Gabriel looked up. There was indeed plenty of light. The moon was full, which made for strong magic. And a full moon on Midsummer Night, well, Gabriel knew his lore well: that was the one night when magic powers were bound by no limits.

Zeb disappeared into the oaks. Gabriel, a noted footracer with three Shipham Fair blue ribbons to his credit, had nearly caught up when SMACK! BANG! There were claps like thunder. Gabriel dove behind a tree and peered out.

In the center of a clearing just ahead sat the Wimblestone, and on a mossy bed in front of it lay Zeb, snoring as if in a deep sleep. Round about him circled tall, pale folk, and they were chanting. Gabriel felt drawn to their dangerous beauty the same way one feels the wild urge to jump when standing on a cliff. He shuddered. These were People of the Hills: the faeries. Elven folk.

Midsummer Night was the night of the People of the Hills.

Images of the enchanted Rollright Stones of Oxfordshire flashed into Gabriel’s mind. Folk said the spirits of an ancient king and his knights were imprisoned long ago in these stones, and that they rolled down to the river some nights to drink. Did the People of the Hills mean to imprison his brother in stone, too?

From his memory welled the words of a boyhood game. He rose, cupped his hands to his mouth, and—slightly altering the verse in keeping with the situation—called out:

Elf or faerie, bonny sprite,

Leave him – chase me if ye might!

And if I’ve won come morning light,

You’ll set him free and show no spite.

Because I challenge in plain sight,

As mortals ye must race tonight!

Then he turned and ran.

It was only a game, of course, but it was all he could think to do. He hoped it would at least prevent the People of the Hills from using magic on him—that it would bind them in honor to an honest competition in an age-old dare, a challenge. A footrace. But if they won . . . if they won, they might get two souls to imprison in stone—his own and his brother’s.

Legend had it faeries were light footed and quick, able to run for miles and never leave a footprint. Gabriel did not look back until he had cleared the wood and was into the field. The People of the Hills were coming like shadows. He could see the glint of their green eyes and pale faces in the moonlight. They sprang like cats, their feet barely touching the ground. And they called to him in fell voices to come back to them.

Up over the crest of Wimblestone Hill Gabriel pressed, plunged down into the lane, across it, and on into the next field. He knew what he had to do: he had to run all night, without stopping, fast enough to keep the People of the Hills from catching him, for they would never tire. They could go on forever. And always they called to him, urging him to give in.

Gabriel broke through a hedgerow and into another field. He ran up the lane into Shipham, and then beyond it, past little hamlets and farms. By now he had been running for nearly an hour, yet the stars had turned but a little, and the moon still had a long journey before it sank on the other side of the sky. Hours, still, to go, and Gabriel was tiring. Something brushed his shoulder. A chill ran down his spine. Out of the corner of his eye he saw a graceful white hand reach out for him.

That’s when Gabriel got mad, and when Gabriel got mad, he got determined. So he called on his will to hold like iron and sped up, running into the night, and before he knew it, he had run all the way to the Stone Circles of Stanton Drew. The faeries were just behind, but as his lungs heaved and his heart knocked at his ribs, he thought of his brother lying spellbound in the forest. A new wave of determination pumped his legs on.

The lay of the land turned him southerly, and eventually he skirted the old hill fort of Bratton Castle, made ages ago by forgotten peoples. Soon he’d passed into Wiltshire and come out onto Salisbury Plain with its many barrows. And as Gabriel passed these lonely places, he noticed that the crowd that followed him was growing. Whether alive or dead, men or elves, he did not know, but the taunting had stopped, and now he was surprised to hear laughter as if in the merry meeting of old friends.

By the time he reached the great ring of Stonehenge on the high, treeless plain, it was the deepest hour of the night. The towering lintel arches shown white in the moonlight, like doorways to a distant past. The crowd behind him seemed to be hundreds, maybe thousands, strong. They broke out in song when they saw the great stones. More curious by the minute, Gabriel decided to run right round the ring to better see the numbers that now followed him. Knowing his lore, he went widdershins, keeping the stones to his left side.

And as he did, a girl’s voice cried out from amongst the throng across the wide circle. “They say if you’ll run ’em all the way to the Rollright Stones up north, they’ll do your brother no harm, and, what’s more, they’ll give you the gold as a thankee. They ain’t had such a merry time in three thousand years!”

Gabriel looked, and there in the midst of all the pale, ghostly faces was one of mortal color, a pretty lass, bright-eyed and raven-haired.

“I’m Gabriel!” he called to her.

“I’m Jenny. They took me from the cradle and left a changeling in my stead. But they say, if you’ll do as they asks, they’ll set me free.”

So Gabriel turned north. He ran between Silbury Hill and the Kennet Barrows, to Avesbury Circle where he went widdershins round the Devil’s Chair Stone a hundred times so its magic would aid him. Then, feeling strong as a stag, he ran past old Barbury hill fort and the Long Barrow of Liddington; beyond Dragon Hill and the White Horse of Uffington, carved out of the chalk and shining silver in the moonlight. Nearly six hundred miles, Gabriel reckoned, since he’d begun, all the way to the Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire.

The rosy glow of dawn was just blushing up the eastern sky.

No longer afraid, Gabriel pulled Jenny into the middle of the ring of rough-hewn stones that stood like jagged teeth. The People of the Hills cheered. Then they gave way, bowing, to let Gabriel and Jenny pass free. Gabriel and Jenny walked the long road back to Shipham, where they stopped to slake their parched throats at the inn, and found his brother Zeb enjoying a pint with a friend.

“Gabriel! Where have ye been? Why, ye look all spent, brother! Sit down! Yon lassie, too. Come take a bite with Dick and me.”

Gabriel’s face broke into a grin of delight. “Why, Zeb, you’re here!”

“Why, of course I’m here,” replied he. “Where else would I be? Gabe, I had the most amazin’ dream last night, and what do you think it was? I dreamt the old Wimblestone has a heap o’ gold under it, now what do ye think o’ that?”

“We was just sayin’ we should haul pick and shovel up there sometime,” added Dick earnestly. “Take a peek.”

“Think of it! We’d be rich!” Zeb exclaimed, turning to his brother. But Gabriel had fallen asleep at the table. Jenny had, too, her head against his shoulder.

Zeb turned to Dick. “Sometimes I wish Gabe were a wee bit more adventurous,” he said wistfully.

After that, Zebedee Fry was more restless than ever. He eventually set off in search of adventure and fortune. But Gabriel and Jenny settled down in Shipham and raised a family. They never did take the gold. Gabriel said what would he want with gold, since he had everything he needed right there in his own home already. He and Jenny never told anyone of the Wimblestone’s dance nor of the footrace with the People of the Hills. But on Midsummer nights they always kept their children warm and safe inside their home with stories by the fire.

All his long and happy life Gabriel Fry walked the lanes of Shipham. Whenever he could, he took the way past the great, gray Wimblestone. There it sat for the rest of his days, seemingly forever still. All the same, Gabriel never failed to give it a nod and a tip of his hat.

THE END

Kenmare Stone Circle, Ireland

Kenmare Stone Circle, Ireland

Leave a comment