Keywords: werewolves, Thirty Years’ War, soldiers, greed, human-animal hybrids

Times of war had been shown to increase the rate of wolf attacks as wolves became attracted to the corpses left on the battlefield. This would have led to wolves becoming habituated with humans, becoming less fearful and more likely to attack as episodes in recent history have shown (Fritts, Stephenson, Hayes, 2010, p. 303). The Thirty Years’ War was one of the deadliest wars in human history. German territories suffered the greatest losses with an estimate of over seven million, with some regions losing as much as 50 per cent of its population through battle, disease, and famine (Ruff, 2001, p. 60). This large death toll would have no doubt attracted carnivorous animals, as there would have been a struggle to swiftly bury the dead after huge losses.

During the midst of the war through the 1630s, there was a large cluster of werewolf reports and a new wave of witch-persecutions that correlate with the Catholic reconquests (http://www.elmar-lorey.de/Prozesse.htm). Rolf Schulte has claimed that slander cases accusing people of werewolves also paralleled with the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War (Schulte, 2015, p. 191). Schulte showed that slander cases involving accusations of being a werewolf were relatively common with it consisting of 17 per cent of all slander cases during the early seventeenth century. While the mounting bodies of dead soldiers and civilians could have attracted hungry wolves, accusations of people being a werewolf also occurred in areas that were not particularly populated by wolves (Schulte, 2015, p. 196).

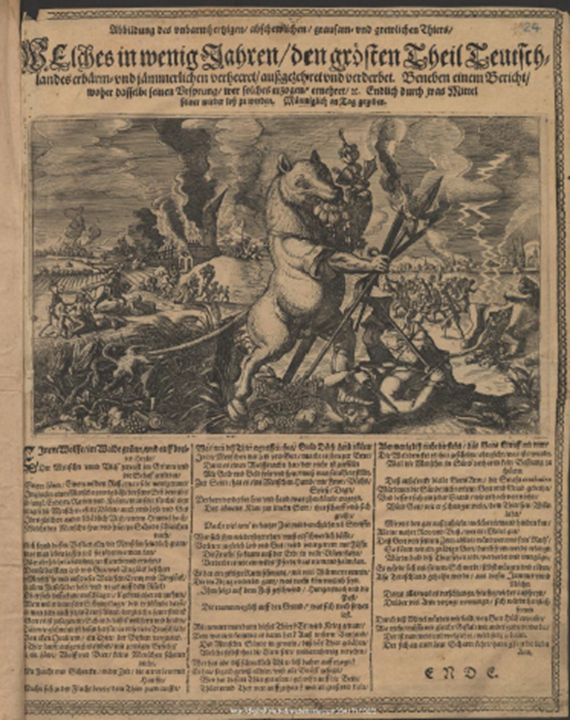

Engraving, Sheet: 34.6 x 27.7cm; Illustration: 16.1 x 25.9cm,

State and University Library Dresden

The wolf-headed soldier recalls the ancient Germanic ‘warrior wolf tradition,’ where the wearing of wolf skins and adopting the animalistic ferocity of the wolf was used in battle (Cheilik, 1987, p. 269). These ancient Germans were believed to have gained their power from the Germanic god, Wodan, or Wotan, who was also the god of war and the wolf (Speidel, 2004, p. 30). The wolf, therefore, served as the perfect metaphor for the tyranny of war, with its ancient roots. It acted as a motif for the murderous brutality and destruction caused by the greedy military during the years of the early-seventeenth century as evidenced by an anonymous broadsheet printed in c.1630. Instead of the military framed for its heroism and as protectors, they were stigmatised for their bloody work in a similar way that executioners were (Mellinkoff, 1993, p. LI-LII). The armies of early modern Europe were despised for the havoc they caused to villagers who suffered the most during times of war. As armies were insufficiently paid and therefore unfed, they resorted to plundering peasants that often turned violent. As stated in the anonymous broadsheet: ‘Whoever stands up to it, has to suffer greatly, loses his life and goods at the same time, is being trampled with feet.’

The wolf-hybrid represents the destruction soldiers had on villagers. The wolf-headed beast depicted on the broadsheet has the body and hoof of a horse, a long rat’s tail, a lion’s paw, and an arm and left leg of a human. The body of the horse likely symbolised the horses the soldier’s rode, trampling people underfoot. This is illustrated by the soldier in the background on the left, trampling a woman who has been knocked to the ground ‘like a wild horse which nobody can stop.’ The horses’ hoof further served to symbolise the destruction to crops causing famine. As with the climatic shift of the late 1590s, famine during the Thirty Year’s War also correlates with the resurgence of witch persecutions and werewolf accusations (Hsia, 1989, p. 160). The destruction of crops was often deliberate by foreign military attacking the civilian population as well as crippling the defences of the local armies (Ruff, 2001, p. 56). The poisonous rat’s tail symbolised the diseased animal that spread pestilence. It represents the disease the army spread throughout civilian populations including dysentery, influenza, typhus, and the bubonic plague (Ruff, 2001, p. 61). Besides the tail of the wolf-hybrid, frogs, serpents, and locus are depicted destroying crops. These creatures were further representative of swarms of the apocalypse, thus associating the soldier with an apocalyptic beast (e.g. Revelation 16.13).

The ruffles around the human elbow resembling a shirt pushed back gives the appearance that underneath the animal body is a human in disguise of the beast. This image portrays the human as the real monster that was to be feared. The human hand holds onto weapons and a torch that has likely lit the fires destroying the villages in the distance, highlighting his violent nature. His human leg is dressed as a knight (sabaton) and is crushing a soldier’s head underneath. On the one hand, the soldier has been marginalised as they were often poor and unfed requiring local villages to survive. On the other hand, as the depiction of the wolf-hybrid soldier illustrates, he was also symbolic of murderous tyrants who ‘spares no human being.’ The blurring line between human and beast was described in the text by stating: ‘one does not trust a lion, a wild horse very much, the same for a person who is angry, mean, who lost his senses.’

Although the place of publication for the broadsheets are unknown, they would have been printed in one of the major printing centres in the larger fortified cities. Therefore, the broadsheets were published by and for an audience significantly less affected by the worst ravages of the war. The text provides a moralistic framework in which to view the engraving. The broadsheet ends with laying the blame for the beast of war on the collective sins of the German people who had fed the war in one way or another. Although the countryside was the battleground, it was from the cities that war was waged. The beast was punishment from God, and only repentance will destroy the beast. Therefore, the broadsheet appears to serve as a call to action to end its atrocity.

Although the Thirty Years’ War originated as a religious conflict, it ceased to be its central focus after 1630 (Monter, 2006, p. 274). The wolf’s head was symbolic of the soldiers’ greed as well as murderous rampage who ‘tears apart people and livestock.’ Underneath the beast’s feet and among the apocalyptic animals are vines and grapes referencing Matthew 20.1-16, comparing the Kingdom of Heaven to a vineyard. Christ called himself ‘the true vine’ in John 15.1, therefore the soldier was representative of the rejection of Christ. Instead of fighting for religion, he was fighting to fulfil his insatiable greed.

The greedy wolf motif is evident as the wolf holds onto treasures in his lion’s claw and jaws, symbolic of a ravenous wolf whose ‘mouth which cannot be filled.’ In the distance to the right, another wolf hybrid’s stomach has been torn open from a bolt of lightning. The contents of its stomach reveals that it has consumed all the treasures that had been stolen from the multiple burning villages in the background. The lightning strike symbolises that God will eventually punish the wicked. Therefore, the wolf-hybrid ‘others’ soldiers by representing their selfish, greedy pillaging and murderous rampaging of villages during the war.

Broadsheet Translation

Depiction of the merciless, abominable, and gruesome animal, which within a few years ravaged, starved, and wasted the greatest part of Germany. Below here is a report from where this creature originated, who raised and fed it, and finally by what means one can rid of it again. Here [bravely] described.

A wolf in the green forest and on wide heath, which tears apart people and livestock, and who scatters sheep with fierceness, one does not trust a lion, a wild horse very much, the same for a person who is angry, mean, who lost his senses; many a person is very afraid of snakes, vipers, rats, and toads, so the people often wrestle in distress also to save themselves and their goods, the same with other harmful creatures under the high heavens, which day in and day out sneak to harm people. It seems to me that all people bear ill will toward these beasts, one should not let any of them live, shall kill them when one can. But whoever loves such creatures, raises and feeds them, is provided with a lot of misfortune for his body and goods. The person who diligently fetches for himself in this way his cross and misfortune and carries it on his back, if he could get rid of it, but does not desire to do so, to whom will he then complain about his adversity, which he is getting because of it. Can one find [many] such people now also in Germany? […] God, it is a shame that one has to say that from here and there then quickly has come forth into our dear Germany from all quarters an animal, the aforementioned beast. That animal runs around upright, with a furious face, [like] a lion, wolf, and bear, it spares no human being. With fear and terror now the poor people in groups are preparing to flee, to run away from the animal.

Whatever this animal now grasps, towns, villages, land, and people, yes the people, body and goods, it makes it its prey. For it has a wolf’s mouth which cannot be filled. With gold and money all day long one has to feed its meanness. At its side it has the hand of a human being, with fire, rifle, spear, rapier, and destroys people and land, whatever comes toward it. The lion’s claw at its left side reaches sharply around, makes many a one poor in a short time with pulling through of stripes [translator note: This means that the claws scraped through everything, making scratch marks.]. Whoever stands up to it, has to suffer greatly, loses his life and goods at the same time, is being trampled with feet. The fruit, which has barely sprouted from the earth, was blooming fully, the beast destroys it like a wild horse which nobody can stop. It has a poisonous rat’s tail with a lot of unclean worms on it, which, when the beast retreats, destroys entirely what could still be useful. It is followed quickly by famine and pestilence, which clear away whatever can still be found. What is the name of this animal? It is called war. From where then does it come? From our fatherland. The people’s sin in general has given birth to this evil animal, which even eats up its own parents mercilessly. Who has raised this horrible animal so far? I say, surely here, it had sucked on all of our breasts. Who has cruelly helped this animal up on its feet, opened wide door and gate? All of us, big and small.

But few people understand this correctly, that God’s punishment acts with this. The world thinks it happens just so, it is no [wonder]. Because the people persist in sin, no improvement can be felt. That God’s arm stays extended, the punishments continue. If the sin now would not be recognized and God not be asked for grace, and if every social class would not improve, as is much needed, God would, as he did often, let the animal have its will and let it play to the end that which nobody can prevent. True remorse and repentance alone would be a good means that God would let go of his wrath, would move away from us His “rood”, thus we could attain a merciful God; by becoming pious we would soon see this animal dead, destroyed and perished. It would strangle and kill itself with its own sword. This way Germany could be helped from this vale of tears and destitution, in addition, everything that had been gobbled up would often be spit out again. In addition, many poor people who had been chased away, driven out, would be wonderfully glad, if they didn’t have to perish entirely like so many others. He is wise now and well educated, will be blessed, who cares about other people’s adversity, this is what the old ones have said.

E n d.

Translation by Gerda Dinwiddie

Bibliography:

Michael Cheilik, ‘The Werewolf,’ in Malcolm South (ed.), Mythical and Fabulous Creatures: A Source Book and Research Guide, New York: Greenwood Press, 1987, pp. 265-93.

Steven H. Fritts, Robert O. Stephenson, Robert D. Hayes, and Luigi Boitani, ‘Wolves and Humans,’ in L. David Mech and Luigi Boitani (eds.), Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 289-317.

R. Po-chia Hsia, Social Discipline in the Reformation Central Europe 1550-1750, London: Routledge, 1989.

David Lederer, ‘Fear of the Thirty Years War,’ in Michael Laffan and Max Weiss (eds.), Facing Fear: The History of an Emotion in Global Perspective, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012, pp. 10-30.

Elmar Lorey http://www.elmar-lorey.de/Prozesse.htm

Ruth Mellinkoff, Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages, Volume One: Text, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993.

William Monter, ‘Religious Persecution and Warfare,’ in Alec Ryrie (ed.), Palgrave Advances in European Reformations, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2006.

Julius R. Ruff, Violence in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Rolf Schulte, ‘The Werewolf in Popular Culture of Early Modern Germany,’ in Willem de Blécourt (ed.), Werewolf Histories, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 185-205.

Michael Speidel, Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan’s Column to Icelandic Sagas, London: Routledge, 2004.

H. R. Trevor-Roper, The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, the Reformation and Social Change, New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

Gary K. Waite, ‘Sixteenth-Century Reform and Witch-Hunts’, in Brian P. Levack (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 485-507.