Practice Essentials

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world. Most surgeons now prefer to perform a tension-free mesh repair. The Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty is currently one of the most popular techniques for repair of inguinal hernias.

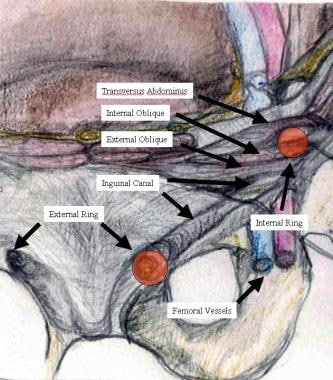

The image below depicts the anatomy of the inguinal canal.

Indications and contraindications

The existence of an inguinal hernia has traditionally been considered sufficient reason for operative intervention. However, the following considerations should be taken into account:

-

Some studies have shown that the presence of a reducible hernia is not, in itself, an indication for surgery and that the risk of incarceration is less than 1%

-

Symptomatic patients should undergo repair

-

Even asymptomatic patients who are medically fit should be offered surgical repair

-

Because of the higher frequency of femoral hernias in women, procedures that provide coverage of the femoral space (eg, laparoscopic repair) at the time of initial operation may be better suited for women as primary repairs

Inguinal hernia repair has no absolute contraindications. However, the following considerations should be taken into account:

-

Any medical issues should be fully addressed beforehand and the operation delayed accordingly

-

Patients with elevated American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores and high operative risk should undergo a full preoperative workup and determination of the risk-to-benefit ratio

-

Recurrences after a primary posterior technique may be treated with Lichtenstein hernioplasty; recurrences after a primary anterior technique should be treated with TEP, TAPP, or open posterior repair

-

Asymptomatic reducible direct inguinal hernia in an elderly patient with multiple uncontrollable comorbidities and an elevated ASA score does not require repair and may be left alone for close observation and follow-up

See Overview for more detail.

Preparation

No special equipment is required for inguinal hernia repair. Instruments and materials on hand may include the following:

-

Syringe

-

25-Gauge needle

-

Surgical knife with blade

-

Mosquito forceps

-

Dissecting scissors

-

Polypropylene or polyester mesh

-

Langenbeck retractors

-

Adson thumb forceps

-

Needle holder

-

Sutures (absorbable or nonabsorbable)

-

Penrose drain or umbilical tape

Inguinal hernia repair can be performed with the following types of anesthesia:

-

General

-

Regional (spinal epidural)

-

Local (infiltration field block)

For Lichtenstein hernioplasty, local anesthesia is safe and generally preferable. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely indicated in low-risk cases but may be considered when risk factors are present.

See Periprocedural Care for more detail.

Procedure

Inguinal hernia repairs are of the following three general types:

-

Herniotomy (removal of the hernial sac only)

-

Herniorrhaphy (herniotomy plus repair of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal)

-

Hernioplasty (herniotomy plus reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal with a synthetic mesh)

The Lichtenstein tension-free mesh repair, which is an example of hernioplasty and is currently one of the most popular open inguinal hernia repair techniques, includes the following components:

-

Opening of the subcutaneous fat along the line of the incision

-

Opening of the Scarpa fascia down to the external oblique aponeurosis and visualization of the external inguinal ring and the lower border of the inguinal ligament

-

Opening of the deep fascia of the thigh and exposure of the femoral canal to check for a femoral hernia

-

Division of the external oblique aponeurosis from the external ring laterally for up to 5 cm, safeguarding the ilioinguinal nerve

-

Mobilization of the superior (safeguarding the iliohypogastric nerve) and inferior flaps of the external oblique aponeurosis to expose the underlying structures

-

Mobilization of the spermatic cord, along with the cremaster, including the ilioinguinal nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, and the spermatic vessels; all of these structures may then be encircled in a Penrose drain or tape

-

Opening of the coverings of the spermatic cord and identification and isolation of the hernia sac

-

Inversion, division, resection, or ligation of the sac, as indicated

-

Placement and fixation of mesh to the edges of the defect or weakness in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal to create a new artificial internal ring, with care taken to allow some laxity to compensate for increased intra-abdominal pressure when the patient stands

-

Resection of any nerves that are injured or of doubtful integrity

-

In males, gentle pulling of the testes back down to their normal scrotal position

-

Closure of spermatic cord layers, the external oblique aponeurosis, subcutaneous tissue, and the skin

Other approaches to open inguinal hernia repair include the following:

-

Plug-and-patch repair - This adds a polypropylene plug shaped as a cone, which can be deployed into the internal ring after reduction of an indirect sac

-

Prolene Hernia System (PHS) - This consists of an anterior oval polypropylene mesh connected to a posterior circular component

-

McVay repair - In this approach, the conjoined (transversus abdominis and internal oblique) tendon is sutured to the Cooper ligament with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures

-

Bassini repair - This approach involves suturing the transversalis fascia and the conjoined tendon to the inguinal ligament behind the spermatic cord, as well as placing a vertical relaxing incision in the anterior rectus sheath

-

Shouldice repair - This is a four-layer procedure in which transversalis fascia is incised from the internal ring laterally to the pubic tubercle medially, upper and lower flaps are created and then overlapped with two layers of sutures, and the conjoined tendon is sutured to the inguinal ligament (again in two overlapping layers)

-

Darn repair - This is a pure-tissue tensionless technique that is performed by placing a continuous suture between the conjoined tendon and the inguinal ligament without approximating the two structures

See Technique for more detail.

Background

Hernias are abnormal protrusions of a viscus (or part of it) through a normal or abnormal opening in a cavity (usually the abdomen). They are most commonly seen in the groin; a minority are paraumbilical or incisional. In the groin, inguinal hernias are more common than femoral hernias.

Inguinal hernias occur in about 15% of the adult population, and inguinal hernia repair is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world. [1] Approximately 800,000 mesh hernioplasties are performed each year in the United States, [2] 100,000 in France, and 80,000 in the United Kingdom.

There is morphologic and biochemical evidence that adult male inguinal hernias are associated with an altered ratio of type I to type III collagen. [3] These changes lead to weakening of the fibroconnective tissue of the groin and development of inguinal hernias. Recognition of this process led to acknowledgment of the need for prosthetic reinforcement of weakened abdominal wall tissue.

Given the evidence that the use of mesh lowers the recurrence rate, [4, 5] as well as the availability of various prosthetic meshes for the reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, most surgeons now prefer to perform a tension-free mesh repair. Accordingly, this article focuses primarily on the Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty, which is one of the most popular techniques used for inguinal hernia repair. [6, 7]

Types of hernia

An indirect hernia is defined as a defect protruding through the internal or deep inguinal ring, whereas a direct hernia is a defect protruding through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. To put it in a more anatomic way, an indirect hernia is lateral to the inferior epigastric artery and vein, whereas a direct hernia is medial to these vessels. The Hesselbach triangle is the zone of the inguinal floor through which direct hernias protrude, and its boundaries are the epigastric vessels laterally, the rectus sheath medially, and the inguinal ligament inferiorly. [8]

An incomplete hernia is confined to the inguinal canal, whereas a complete hernia comes out of the inguinal canal through the external or superficial ring into the scrotum. Direct hernias are always incomplete, whereas indirect hernias can also be complete.

A sliding inguinal hernia is one in which a portion of the wall of the hernia sac is made up of an intra-abdominal organ. As the peritoneum is stretched and pushed through the hernia defect and becomes the hernia sac, retroperitoneal structures such as the colon or bladder are dragged along with it and thus come to make up one of its walls.

Bilateral pediatric hernias are most commonly indirect hernias and arise because of the patency of the processus vaginalis. Simple ligation of the hernia sac (herniotomy) alone is enough. Surgical treatment of indirect hernias in adults, unlike that in children, requires more than simple ligation of the hernia sac. This is because the patent processus is only part of the story. With time, the internal ring dilates, leaving an adult with what can be a sizable defect in the floor of the inguinal canal; this must be closed in addition to division or reduction of the indirect hernia sac.

A hydrocele is a commonly encountered pathology related to hernias. A communicating hydrocele is, by definition, a form of indirect hernia, albeit with an extremely small defect through which only peritoneal fluid enters the sac but no viscus (eg, omentum or bowel) comes out.

Types of hernia repair

Inguinal hernia repairs may be divided into the following three general types:

-

Herniotomy (removal of the hernial sac only) - This, by itself, is adequate for an indirect inguinal hernia in children in whom the abdominal wall muscles are normal; formal repair of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal is not required

-

Herniorrhaphy (herniotomy plus repair of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal) - This may be suitable for a small hernia in a young adult with good abdominal wall musculature; the Bassini and Shouldice repairs are examples of herniorrhaphy

-

Hernioplasty (herniotomy plus reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal with a synthetic mesh) - This is required for large hernias and hernias in middle-aged and elderly patients with poor abdominal wall musculature; the Lichtenstein tension-free mesh repair is an example of hernioplasty

Open vs laparoscopic repair

Although numerous surgical approaches have been developed to treat inguinal hernias, the Lichtenstein tension-free mesh-based repair remains the criterion standard. [1] In a Cochrane review comparing mesh with nonmesh open repair, the evidence was sufficient to conclude that the use of mesh was associated with a reduced rate of recurrence. [2]

Laparoscopic approaches are feasible in expert hands, but the learning curve for laparoscopic hernia repair is long (200-250 cases), the severity of complications is greater, detailed analyses of cost-effectiveness are lacking, and long-term recurrence rates have not been determined. [9] The role of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in the treatment of an uncomplicated, unilateral hernia is yet to be resolved.

Nevertheless, transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty may offer specific benefits for some patients, such as those with recurrent hernia after conventional anterior open hernioplasty, those with bilateral hernias, and those undergoing laparoscopy for other clean operative procedures.

A 2014 meta-analysis of seven studies comparing laparoscopic repair with the Lichtenstein technique for treatment of recurrent inguinal hernia concluded that despite the advantages to be expected with the former (eg, reduced pain and earlier return to normal activities), operating time was significantly longer with the minimally invasive technique, and the choice between the two approaches depended largely on the availability of local expertise. [10]

For further details on the debate over laparoscopic versus open repair, see Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair. For information on manual reduction of hernias, see Hernia Reduction.

Indications

Classically, the existence of an inguinal hernia, in and of itself, has been considered reason enough for operative intervention. However, some studies have shown that the presence of a reducible hernia is not, in itself, an indication for surgery and that the risk of incarceration is less than 1%. [11]

Patients experiencing symptoms (eg, pain or discomfort) should undergo repair; however, as many as one third of patients with inguinal hernias are asymptomatic. [11] The question of observation versus surgical intervention in this asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic population was addressed in two randomized clinical trials. [6, 7] The two trials yielded similar results: After long-term follow-up, no significant difference in hernia-related symptoms was noted, and watchful waiting did not increase the complication rate.

In one study, the substantial patient crossover from the observation group to the surgery arm led the authors to conclude that observation may delay but not prevent surgery. [11] This reasoning holds particularly true in the younger patient population. Thus, even an asymptomatic patient, if medically fit, should be offered surgical repair. A long-term follow-up study determined that most patients with a painless inguinal hernia will develop symptoms over time and concluded that surgery is recommended for medically fit patients. [12]

Koch et al found that recurrence rates were higher in women and that recurrence was 10 times more likely to be of the femoral variety in women than it was in men. [13] Such findings have led some to the conclusion that procedures providing coverage of the femoral space (eg, laparoscopic repair) at the time of initial operation are better suited for women as primary repairs. [14]

Contraindications

Inguinal hernia repair has no absolute contraindications. Just as in any other elective surgical procedure, the patient's medical status must be optimized. Any medical issues (eg, upper respiratory tract or skin infection, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, chronic constipation, urinary obstruction, persisting cough, obstruction or strangulation, or allergy to local anesthesia or prosthetic devices) should be fully addressed and the operation delayed accordingly.

Patients with elevated American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores and high operative risk should undergo a full preoperative workup and determination of the risk-to-benefit ratio.

Recurrences after a primary posterior technique (eg, TEP, TAPP, or open posterior repair) may be treated with Lichtenstein hernioplasty. [5] Recurrence after a primary anterior technique should preferably be dealt with by means of TEP, TAPP, or open posterior repair.

Technical Considerations

Anatomy

A useful learning tool for gaining a working knowledge of the inguinal region is to visualize the region as it is surgically approached in the open technique of hernia repair. The inguinal region is part of the anterolateral abdominal wall, which is made up of the following nine layers, from superficial to deep:

-

Skin

-

Camper fascia

-

Scarpa fascia

-

External oblique aponeurosis

-

Internal oblique muscle

-

Transversus abdominis

-

Transversalis fascia

-

Preperitoneal fat

-

Peritoneum

The first layers encountered upon dissection through the subcutaneous tissues are the Camper and Scarpa fasciae. Contained in this space are the superficial branches of the femoral vessels—namely, the superficial circumflex and the epigastric and external pudendal arteries, which can be safely ligated and divided when encountered.

The inguinal canal can be visualized as a tunnel traveling from lateral to medial in an oblique fashion (see the image below). It has a roof facing anteriorly, a floor facing posteriorly, a superior (cranial) wall, and an inferior (caudal) wall. The canal contents (in men, cord structures; in women, the round ligament) are the traffic that traverses the tunnel.

The external oblique aponeurosis serves as the roof of the inguinal canal and opens just lateral to and above the pubic tubercle. This is the external or superficial inguinal ring, which allows the cord structures egress from the inguinal canal to the scrotum. [15]

The floor of the canal is composed of the transversus abdominis and the transversalis fascia. The entrance to the inguinal canal is through these layers, and this entrance constitutes the internal or deep inguinal ring.

The inferior wall is the inguinal (Poupart) ligament. This ligament is formed by the lower edge of the external oblique aponeurosis and extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to its attachments at the pubic tubercle and fans out to form the lacunar (Gimbernat) ligament. [16, 17] The inguinal ligament folds over itself to form the shelving edge. This folded-over sling of external oblique aponeurosis is the true lower wall of the inguinal canal.

The superior wall consists of a union of the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, which arches from its attachment at the lateral segment of the inguinal ligament over the internal inguinal ring, ending medially at the rectus sheath and coming together inferomedially to insert on the pubic tubercle, thus forming the conjoined tendon. [17, 8]

In males, the contents of the inguinal canal include the obliterated processus vaginalis (which, when patent, forms the sac of the indirect inguinal hernia), the spermatic cord, and the ilioinguinal nerve (which comes out of the superficial inguinal ring along with the spermatic cord). In females, the inguinal canal contains the ilioinguinal nerve and the round ligament of the uterus.

The coverings of the spermatic cord include the following:

-

Internal spermatic fascia, derived from the transversalis fascia at the deep inguinal ring

-

Cremaster muscle, derived from the internal oblique muscle at the deep inguinal ring

-

External spermatic fascia, derived from the external oblique aponeurosis at the superficial inguinal ring (present only in the scrotum and not in the inguinal canal)

The contents of the spermatic cord include the following:

-

Vas deferens

-

Testicular artery

-

Artery of the ductus deferens

-

Cremasteric artery

-

Pampiniform plexus

-

Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve

-

Parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves

-

Lymphatic vessels

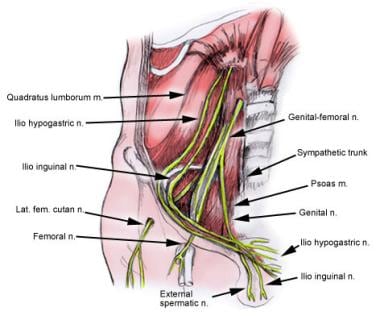

The key nerves in the inguinal region are as follows (see the image below):

-

Iliohypogastric nerve

-

Ilioinguinal nerve

-

Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve

The ilioinguinal nerve runs medially through the inguinal canal along with the cord structures traveling from the internal ring to the external ring. It innervates the upper and medial parts of the thigh, the anterior scrotum, and the base of the penis.

The iliohypogastric nerve runs below the external oblique aponeurosis but cranial to the spermatic cord, then perforates the external oblique aponeurosis cranial to the superficial ring. It innervates the skin above the pubis.

The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve lies within the spermatic cord and travels with the cremasteric vessels through the inguinal canal. It innervates the cremaster muscle and provides sensory innervation to the scrotum.

Some variations in the anatomic distribution of these nerves may be observed—for instance, the occasional absence of an ilioinguinal nerve. [18]

The Hesselbach triangle is bounded by the inguinal ligament below, the lateral border of the rectus abdominis medially, and the inferior epigastric vessels laterally (see the image below). The sac of a direct hernia lies in this triangle, whereas the neck of an indirect hernia sac lies outside the triangle (lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels).

Best practices

Lichtenstein open tension-free mesh hernioplasty is suitable for all adult patients, irrespective of age, weight, general health, and the presence of concomitant medical problems. For patients with large scrotal (irreducible) inguinal hernias, those who have undergone major lower abdominal surgery, and those in whom no general anesthesia is possible, the Lichtenstein repair is the preferred surgical technique.

This operation, performed under local anesthesia, is not difficult to learn (learning curve, 5 cases), and trained surgical residents are able to perform it without compromising the patient’s care and long-term outcome. [19, 20] The procedure is time-tested, safe, and economical, and it does not involve the long operating time characteristic of laparoscopic repairs. [5] In addition, it has a low complication rate and has become the gold standard in open tension-free hernioplasties. [21, 22]

Lichtenstein hernioplasty is well suited for smaller community-based, regional, and teaching hospitals, and it offers good immediate and long-term results. Moreover, the excellent results achieved with this repair appear to be unrelated to the surgeons’ level of experience. The technique has been evaluated in large series and has become popular among surgeons all around the world.

In a comparative study of open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair, Lichtenstein’s operation was similar to mesh-plug or Prolene Hernia System (PHS; Ethicon, West Somerville, NJ) repair in terms of time to return to work, complications, chronic pain, and hernia recurrence in the short-to-middle term. [23] Indeed, postoperative pain after a Lichtenstein hernioplasty is minimal; according to a meta-analysis of all reported randomized studies, the pain is comparable to that occurring after laparoscopic repair. [24]

Use of mesh for repair

Emphasizing the Halsted principle of no tension, the Lichtenstein group advocated routine use of mesh in 1984. The prosthesis used to reinforce the weakened posterior wall of the inguinal canal is placed between the transversalis fascia and the external oblique aponeurosis and extends well beyond the Hesselbach triangle. Mesh implants do not actively shrink, but they are passively compressed by the natural process of wound healing. Mesh shrinkage occurs only to the extent to which the tissue contracts.

A mesh with a small pore size is likely to shrink more. Shrinkage of the different types of mesh in vivo is in the range of 20-40%; thus, it is important for the surgeon to ensure that the mesh adequately overlaps the defect on all sides. It is advisable to use a large (eg, 7.5 × 15 cm) sheet of mesh extending approximately 2 cm medial to the pubic tubercle, 3-4 cm above the Hesselbach triangle, and 5-6 cm lateral to the internal ring so as to allow for mesh shrinkage.

Although the use of traditional microporous or heavyweight polypropylene meshes over the past two decades has reduced the recurrence rate after hernia surgery to less than 1%, a major concern has been the formation of a rigid scar plate that causes patient discomfort and chronic pain, impairing quality of life. More than 50% of patients with a large mesh prosthesis in the abdominal wall complain of paresthesia, palpable stiff edges of the mesh, or physical restriction of abdominal wall mobility. [4]

It was assumed that the flexibility of the abdominal wall is restricted by implantation of excessive foreign material and by excessive scar tissue formation. A better knowledge of the biomechanics of the abdominal wall and the influence of mesh on those mechanics has led to the current understanding that “less is more.”

In other words, a less-dense, lighter-weight mesh with larger pores, though still stronger than the abdominal wall and thus usable for the purposes of repair, will result in less inflammation, better incorporation, better abdominal wall compliance, greater abdominal wall flexibility, less pain, and possibly less scar contraction; therefore, its use will lead to a better clinical outcome. [5, 25]

Lightweight composite mesh was developed in the conviction that the ideal mesh should be just strong enough to handle the pressure of the abdominal wall while remaining as low in mass and as thin as possible. The advantage of increasing the mesh pore size is that it makes it easier for tissue to grow through the pores and thereby create a thinner, better-integrated scar.

The newer lightweight composite meshes offer a combination of thinner filament size, larger pore size, reduced mass, and increased percentage of absorbable material. Thus, less foreign material is implanted, the scar tissue has greater flexibility (with almost physiologic abdominal wall mobility), there are fewer patient complaints, and the patient’s quality of life is better.

The use of lightweight mesh for Lichtenstein hernia repair has not been shown to affect recurrence rates, but it has been found to improve some aspects of pain and discomfort 3 years after surgery. [26] According to data from randomized, controlled trials and retrospective studies, light meshes seem to have some advantages with respect to postoperative pain and foreign body sensation. [5, 27]

Complication prevention

Since the widespread acceptance of mesh-based repairs and the significant reduction of inguinal hernia recurrence, the most vexing complication of herniorrhaphy has been chronic groin pain. Causalgia syndromes of each of the three nerves of the groin (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) are well described. [17, 8] There remains some controversy as to whether the nerves should be sectioned or preserved. [28, 29] Current recommendations favor nerve identification and preservation. [14, 30, 31]

The ilioinguinal nerve, which runs anterior to the spermatic cord, can be protected by employing gentle dissection and by isolating the nerve behind a leaf of the incised external oblique aponeurosis with a straight hemostat clamp.

The iliohypogastric nerve can be injured when creating the superior flap of the external oblique aponeurosis and by a bite taken when fixing the mesh to the conjoint tendon.

Another cause of significant postherniorrhaphy pain is the placement of a stitch into the periosteum. This is often the point of maximal postoperative tenderness; accordingly, the surgeon must maneuver with care when anchoring the pubic tubercle bite. [32, 33]

Toward the deep inguinal ring, the hernia sac becomes thin and fragile and adheres more closely to the spermatic cord. Caution should be exercised in dissecting the hernia sac to avoid injury to the cord structures and splitting of the neck of the sac. In adults, the rate of vas deferens injury is estimated at 0.3%. To protect against such injury, the surgeon must always remain aware of the posterior location of the vas deferens when dissecting the hernia sac.

If reduction of the hernial sac proves difficult at operation, a sliding hernia should be suspected. The cecum (on the right side), the sigmoid colon (on the left side), and the urinary bladder (on either side) form the wall of the sac of a sliding hernia; they are not the contents of the hernial sac and are not inside the sac. In a sliding hernia, it is difficult to separate the hernial sac from the structures that form its wall; thus, the hernial sac should be reduced en masse along with these structures, without any attempt to separate them from the hernial sac.

In a complete indirect inguinal hernia, which descends into the scrotum, it is not necessary to remove the entire hernial sac; the sac may be transected in the distal inguinal canal, and the distal part of the sac in the scrotum can be left behind. Hemostasis, however, should be ensured at the cut edge of the distal part of the hernial sac to prevent bleeding and scrotal hematoma. In addition, to prevent the formation of a hydrocele, the distal sac should not be closed.

If it is not possible to return the contents of the hernial sac to the peritoneal cavity even after the sac has been opened, a sliding hernia is likely. Because the viscus is not inside the sac but makes up part of the wall of the sac, any attempt to excise the complete sac is likely to injure the viscus. Only that part of the sac that is distal to the sliding viscus should be excised; the sac is then closed, and the remaining sac, along with the viscus, is reduced into the extraperitoneal space.

Inguinal hernia in a child (even a neonate) should be repaired as early as possible; because the neck of the hernia sac is very narrow, the risk of complications is very high. In children, the superficial and deep inguinal rings almost overlap each other, with the result that that the inguinal canal is very short. A very small incision is made over the superficial inguinal ring; there is no need to open the inguinal canal. Herniotomy alone is performed, with the hernia sac divided at the superficial ring.

Vascular injury is a less common but reported and potentially disastrous pitfall. It can be avoided by respecting the proximity of the femoral vessels, particularly when the mesh is being sutured to the inguinal ligament. [33] Hematoma formation can be due either to injury of the inferior epigastric vessels or to failure to ligate the superficial subcutaneous veins.

Any aggravating factors (eg, chronic cough, chronic constipation, or urinary straining) should be looked into and controlled, if possible, before any hernia is repaired so as to prevent or reduce postoperative stress on the hernia repair, which may increase the risk of recurrence.

The use of an amply sized (eg, 7.5 × 15 cm) piece of mesh is crucial for minimizing recurrence. It must be large enough to extend 2 cm medial to the pubic tubercle, 3-4 cm above the Hesselbach triangle, and 5-6 cm lateral to the internal ring. It should not be laid under tension, so that its center can achieve a slightly domed configuration, which compensates for the forward protrusion of the transversalis fascia upon standing and for the shrinkage of the mesh over time.

In male patients, a testis may be pulled out of the scrotum while the spermatic cord is being manipulated; accordingly, it is important always to remember to pull the testes gently back down to their normal scrotal position after the procedure is completed.

As in all operations, infection is a concern, but in clinical settings where the rate of wound infection is low (< 5%), there is no indication for the routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis in low-risk patients. However, if any risk factors for wound infection (eg, recurrent hernia, advanced age, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive conditions, or expected prolonged operating times) are present, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. Such prophylaxis should also be used at centers where high wound infection rates are observed in elective settings. [34, 35]

Anticoagulation prophylaxis is generally unnecessary; the duration of the operation is not long, and the patient can be mobilized the same evening.

Outcomes

Since the widespread acceptance of mesh-based repair, the rate of hernia recurrence has fallen substantially, to 1% or less. Consequently, more attention is being paid to other complications, such as postherniorrhaphy chronic pain. [36]

Large studies examining mortality risk from various groin operations found that elective inguinal herniorrhaphy was safe and had a low mortality risk that was similar to or even lower than the standardized mortality in the studied population. [1, 37]

Although pain is more common in the acute postoperative period, it remains chronically severe in 3% of patients, having significant effects on their work and social activities. [38] A large Swedish study found that 30% of postherniorrhaphy patients reported long-term pain or discomfort, 6% of whom experienced pain intense enough to alter their activities of daily living. [39]

Another phenomenon that can be experienced after hernia repair is groin numbness. In a large Scottish study that included more than 5500 patients, this was reported to various degrees in as many as 9%. [39]

Other complications include seroma formation, bruising and hematoma (7% of cases), and wound infection (1-7% of cases). [1, 40]

Ischemic orchitis leading to testicular atrophy or even necrosis is a catastrophic but well-known complication of inguinal hernia repair. Symptoms include painful testicular swelling and fever commencing 2-3 days after surgery. [41] The exact cause of this rare complication is unclear, but it is thought to be secondary to venous thrombosis rather than arterial injury. A high index of suspicion for postoperative ischemic orchitis, in conjunction with emergency testicular ultrasonography, may help avoid orchiectomy.

-

Anatomy of inguinal canal.

-

Anatomy of nerves of groin.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Skin incision.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Division of external oblique aponeurosis.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Cord structures and hernia sac encircled by Penrose drain.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Hernia sac separated from cord structures.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Development of preperitoneal space.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Deployment of Prolene Hernia System (PHS).

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Final position of Prolene Hernia System (PHS) mesh.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Closure of external oblique aponeurosis.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Skin closure.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Draping and incision.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. External oblique aponeurosis with external inguinal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. External oblique aponeurosis with external inguinal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Reflected part of inguinal ligament exposed for fixing inferior edge of mesh.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Inferior flap of external oblique aponeurosis developed to expose inguinal ligament from pubic tubercle to midinguinal point.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Superior flap of external oblique aponeurosis is developed as high as possible to provide ample space for mesh placement.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Lifting up cord with hernia sac medial to external inguinal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Avascular plane between posterior inguinal wall and cord structures.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Cord structures and hernia sac looped along with ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Cremaster muscle picked up to be incised longitudinally between hemostats.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Indirect hernia sac dissected and being separated from lipoma of cord and cord structures.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Lipoma of cord dissected free and excised.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Indirect hernia sac separated from cord structures in midinguinal region toward neck of sac.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Voluminous indirect hernia sac separated from cord structures in midinguinal region up to neck of sac.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Hernia sac being divided near neck.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Contents of hernia sac reduced and proximal end to be sutured closed.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Anterior wall of distal sac incised to prevent hydrocele formation.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Fixation of lower edge of mesh.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. First medialmost stitch in mesh, fixed about 2 cm medial to pubic tubercle, where anterior rectus sheath inserts into pubis.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Same suture is utilized as continuous suture to fix lower edge of mesh to reflected part of inguinal ligament up to internal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Lower edge of mesh sutured to inguinal ligament up to internal inguinal ring. To accommodate cord structures, lateral end of mesh is divided into wider upper (two thirds) tail and narrower lower (one third) tail.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Wider upper tail of mesh is passed underneath cord, and mesh is placed posteriorly in inguinal canal behind spermatic cord.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Fixation of upper edge of mesh.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Slit made in mesh to accommodate iliohypogastric nerve. Two interrupted sutures are taken under vision to fix upper edge of mesh while safeguarding iliohypogastric nerve.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Upper tail is crossed over lower tail around spermatic cord, thus creating internal ring. Lower edges of two tails are tucked together to inguinal ligament just lateral to internal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Tails are then passed underneath external oblique aponeurosis to give overlap of about 5 cm beyond internal ring.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. External oblique aponeurosis sutured with 2-0 polypropylene.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Subcutaneous tissue approximated with 3-0 plain catgut.

-

Open inguinal hernia repair. Skin approximated with 2-0 polypropylene subcuticular suture.

-

Hesselbach triangle. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.