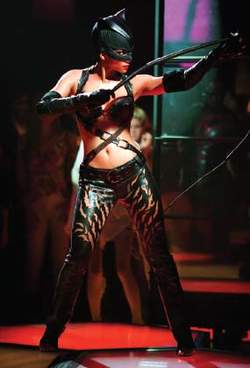

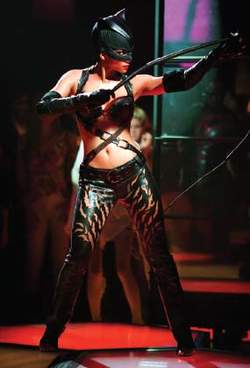

Halle Berry played Catwoman In the 2004 film version. (Warner Bros./DC Comics / The Kobal Collection / Gregory, Doane.)

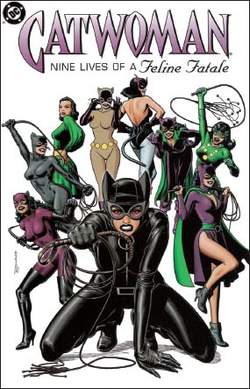

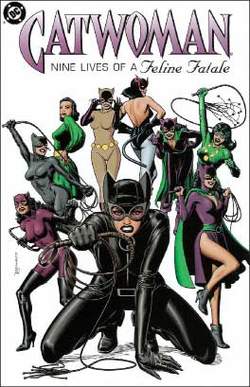

Catwoman: Nine Lives of a Feline Fatale trade paperback © 2004 DC Comics. (Cover art by Brian Bolland.)

Catwoman

(pop culture)Catwoman, slinking in and out of thievery like a mischievous kitten, has titillated Batman throughout most of the Dark Knight’s long career. This “princess of plunder” was envisioned by Batman creator Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger as a female counterpart to the Caped Crusader, and as a means to attract girls to the comics’ readership, but through spunk and tenacity she quickly distinguished herself as much more than a copycat. From her first appearance as “The Cat” in Batman #1 (1940), Gotham City’s most notorious burglar— dressed to the nines (lives?) in a clinging, cleavage-showcasing gown—arouses a side of Batman that the prepubescent Robin finds puzzling. Through each encounter, suggestive repartee between the Bat and Cat intimates that if not for their ethical division, these two would boot the Boy Wonder out of the Batcave and redefine the term “Dynamic Duo.”

When compared to the Joker, Two-Face, and other psychopaths in Batman’s deadly rogues’ gallery, Catwoman, whose penchant for luxuries entices her into a career as a thief, seems tame—but by no means is this lady docile. Wielding a whip with a “cat-o’-nine-tails,” a weapon that by the late 1980s acquired sado-sexual connotations, the cunning Catwoman, with her pugilistic prowess and catlike reflexes, becomes a fierce combatant when cornered or challenged. She had clawed her way through a decade’s worth of stories in random issues of Batman and Detective Comics before her roots were disclosed. In “The Secret Life of Catwoman” in Batman #62 (1950), the villainess reveals her true stripes as she saves Batman’s life, taking a blow to the skull in the process. Once regaining consciousness, she emerges from amnesia with the recollection of her past life as Selina Kyle, flight attendant, and no knowledge of her stint as a criminal. Aiding Batman and Gotham City Police Commissioner Gordon in their apprehension of her former partner in pillage, Kyle is exonerated of her felonies and allowed to set up business as a pet-shop operator. But before long her ego, bruised by taunts from the press and former underworld associates, leads her back into larceny as Catwoman.

While her identity was known to Batman and Gordon, Catwoman’s mystique stymied her adversaries, particularly her ability to resurface after seemingly perishing—did she, like her namesake, really have nine lives? This raven-haired, wide-eyed “felonious feline” also dazzled Gotham’s finest with her wardrobe: Aside from the ghastly full-sized cathead mask she wore during a few early outings, Catwoman skulked about for more than two decades in a stylish purple dress, green cape, and a cat-eared cowl, before streamlining her garb in the 1960s into a form-fitting emerald catsuit that would have made Diana Rigg (TV’s Mrs. Peel) green with envy. By 1969, she’d slipped into a skintight blue bodysuit with a long cat tail, before returning to the purple gear in the mid-1970s. She also frequently cavorted about town in a cat-shaped “kitty” car, took to the air in a catplane, hurled a catarang, and even used a cat-apult to leap to a helicopter while pulling a heist.

Throughout most of her comic book career, Catwoman was portrayed as Batman’s most likeable villain: Sure, she was a bad girl, but not that bad. In the late 1970s, Catwoman’s heart of gold led her to shed her life of crime and marry Bat-man—not in the comics’ regular continuity, but on “Earth-Two,” DC’s parallel world where its characters from the 1940s resided. Their union bore a daughter, Helena, who became the Huntress when the Earth-Two Catwoman was murdered.

Back on “Earth-One,” Catwoman continued to pillage, even after DC Comics jettisoned its multiple-Earth concept in 1985. Selina Kyle was reinvented, along with the Dark Knight, in Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli’s groundbreaking “Batman: Year One” four-issue story arc beginning in Batman #404 (1987). Kyle, it was disclosed, endured an abusive childhood and was on the streets at age twelve, becoming fiercely independent as a result. Seguing into a life of prostitution, this new Kyle was a dominatrix with a butch haircut, who donned a leather catsuit and used her whips on johns before taking to the rooftops as the burglar Cat-woman. More recently, however, Catwoman has given up streetwalking and developed a profound moral sense, albeit one tempered by her hard life. She serves as an occasional ally to Batman and often protects the downtrodden in Gotham City’s seediest neighborhoods.

Catwoman’s popularity was bolstered in the mid-1960s by Julie Newmar’s tantalizing portrayal of the villainess in the popular Batman television show. Newmar sunk her claws into the role, playfully frolicking about with moves so sensuously catlike that all eyes were glued to her while she was on camera. Her immediate successors to the part, Lee Meriwether in the Batman theatrical movie (1966), and Eartha Kitt in later episodes of the television series, never quite commanded the screen as Newmar did. In director Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992), Michelle Pfeiffer’s take on Catwoman rivaled Newmar’s, and spawned a long-delayed but disappointing Catwoman movie, released in 2004, starring Halle Berry as a different Catwoman from Selina Kyle.

Catwoman has also appeared in the numerous incarnations of Batman television cartoon series to appear throughout the years and has been merchandized since the 1960s with items including dolls, action figures, and bubble-bath dispensers. Adrienne Barbeau provided the voice of Catwoman in Batman: The Animated Series (1992–1995), and Gina Gershon voiced Cat-woman in The Batman series (2004–2008).

The first ongoing Catwoman comic book series was launched in 2003, featuring artwork by Jim Balent, who is known for his particularly sexy depictions of the character. The series portrayed her as an antiheroine—a thief and criminal who nonetheless followed her own moral code. She also starts in the noteworthy comics miniseries Catwoman: When in Rome (2004), by the celebrated team of writer Jeph Loeb and artist Tim Sale.

Recently, in the comics, Catwoman has become Batman’s ally. Batman has even confided his secret identity to her, and they have admitted their love for one another. She mostly reformed, although she would still sometimes engage in theft. Starting in 2009 Catwoman co-starred with supervillainesses Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy in the comic book series Gotham City Sirens, originally written by Paul Dini. A new Catwoman series was launched in September 2011, written by Judd Winick and illustrated by Guillem March.

The latest actress to play Selina Kyle onscreen is Anne Hathaway in director Christopher Nolan’s 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises. —ME & PS

The Superhero Book: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Comic-Book Icons and Hollywood Heroes © 2012 Visible Ink Press®. All rights reserved.

Catwoman: Nine Lives of a Feline Fatale trade paperback © 2004 DC Comics. COVER ART BY BRIAN BOLLAND.

Halle Berry as the Feline Fatale in Catwoman (2004).

Catwoman

(pop culture)Prowling along the back-alley fence dividing good and evil while unpredictably playing both sides to suit her purposes, the slinky, kinky Catwoman—aka the Princess of Plunder, the Feline Fatale, and the Mistress of Malevolence—was envisioned as a copycat of Batman. Remarked Batman's originator and first artist, Bob Kane, of the villainess he co-created with Bill Finger, “We also thought that male readers would appreciate a sensual woman to look at.” Modeling her after actress Hedy Lamarr, Kane's first rendition of the raven-haired vixen—as “the Cat” in Batman #1 (1940)—was not in form-fitting Lycra, as one might expect, but instead in a green gown, her curvaceous shape (presumably) accentuated by a torpedo bra and girdle. “What's the matter? Haven't you ever seen a pretty girl before?” she snaps at Batman as he foils her purloining of Gotham's rich and famous on a luxury yacht. Usually careful not to get too close to his foes—except when delivering a well-deserved haymaker— Batman allows the Cat to embrace him, as she flirtatiously offers half of her ill-gotten gain at the suggestion of a … partnership, a notion that stimulates the hero's libido but repulses his ethics. Yet Batman “accidentally” allows the Cat to escape, much to his sidekick Robin the Boy Wonder's surprise, hoping to encounter her again some day. And thus the cat-and-fledermaus game begins. For much of her career Catwoman was essentially a pretty girl who liked pretty things. And if she didn't own what she liked, she'd take it, as Gotham's cat burglar extraordinaire. She scratched her way through a decade's worth of stories before “The Secret Life of Catwoman” in Batman #62 (1950) revealed her true stripes. Knocked unconscious while performing the non-villainous act of saving Batman's life, Catwoman came to with no recollection of her past lives as airline stewardess Selina Kyle or Queen of Crime Catwoman. Aiding Batman and Gotham Police Commissioner Gordon in their apprehension her former criminal partner, Kyle was pardoned and tried the straight and narrow as a petshop proprietor. Before long, in Detective Comics #203 (1954), taunts from the press and the underworld seduced her back into the larcenous nightlife. Playing off of Batman's bat-inspired arsenal, Catwoman's weaponry included her customized, cat-shaped “kitty car,” “catplane,” and “catboat”; a crime-escaping “cat-apult”; a throwable “catarang”; and a secret lair called her Catacomb, overrun with enough felines to fill the Gotham Humane Society. While those gimmicks have been litter-boxed in the twenty-first century, Catwoman's signature weapon remains her “cat-o'-nine-tails” whip, which she cracks with painful accuracy—and if that fails, Catwoman is an agile combatant, hissing, punching, kicking, and scraping (with razor-sharp glove claws) her opponents. She has often seemingly perished, only to resurface, making Batman wonder, Does Catwoman really have nine lives? Catwoman's wardrobe would make Mattel's Barbie (or Barbie's real-life counterpart, Paris Hilton) green with envy, with the exception of the appalling full-sized cathead disguise the Princess of Plunder donned in 1940. Her look during most of comics' Golden Age (1938–1954) was a stylish cat-eared cowl, a purple dress, and green cape, felonious fashions she pulled out of her closet for another go during the 1970s and 1980s. The general public perhaps best recognizes Catwoman in the shimmering, skintight black catsuit popularized by sex-kitten Julie Newmar on the live-action television series Batman (1966–1968). Newmar accepted the Catwoman role at the urging of her college-age brother, who informed her that Batman was a huge hit among Harvard students. The show's campus appeal no doubt increased when the gorgeous Newmar teasingly commanded the camera with sensuously cat-like moves that also entranced little girls hungry for strong female role models, made little boys squirm with prepubescent stirrings, and lured daddies into the den for “family viewing time.” “She was the first person I was aware of that boys wanted to be with and I wanted to be,” said Suzan Colón, author of the light-hearted history Catwoman: The Life and Times of a Feline Fatale (2003), in a 2005 made-for-DVD documentary (accompanying the DVD release of the 2004 theatrical film Catwoman). Newmar's purring of Rs in her campy dialogue, especially with exaggerated words like “perrrrr-fectly,” joined the popculture lexicon. Newmar's immediate successors to the part, Lee Meriwether in the theatrical movie Batman (1966) and Eartha Kitt in later episodes of the television series, each held their own, but it is Newmar who best defined the role with her untouchable performance. The casting of African- American Kitt as Catwoman in Batman's third season raised eyebrows in the racially charged United States of the late 1960s, but in later, more enlightened years has become acknowledged as a historically significant move. During the spate of Batman merchandising inspired by the show, Catwoman was seen on numerous Batman items, but usually in her comic-book interpretation, although Newmar's first Catwoman episode was adapted to handheld “toy” viewing for Batman View-Master reels and See-a-Show filmstrips. CBS's The Batman/Superman Hour (1968–1969) and The Adventures of Batman and Robin (1969–1970) brought Catwoman to Saturday-morning television after the live-action show was canceled. During this period, comics' Catwoman slipped into a green-hued version of the Newmar suit, followed by a skintight blue bodysuit with a bouncy cat tail; this latter costume was the basis for 1970s Catwoman figures produced by toy manufacturer Mego. Meanwhile, the Feline Fatale returned to the tube in The New Adventures of Batman (1977–1978). In the late 1970s, Batman and Catwoman wed—on “Earth-Two,” the parallel reality populated by Golden Age DC Comics characters—and produced a daughter, Helena, who became the superhero the Huntress after the Earth-Two Catwoman was murdered (while the Huntress in twenty-firstcentury DC continuity is not the daughter of Batman and Catwoman, the Huntress of TV's liveaction 2002–2003 series Birds of Prey was). After infrequent 1970s comic-book appearances, Catwoman fared better in the early to mid- 1980s, becoming a semi-regular character in Batman and Detective, often appearing as the reformed Selina Kyle, or fighting alongside Batman as Catwoman. The Joker, unimpressed with Catwoman's change of heart, re-criminalized her in a disturbing experiment in Detective #569–#570 (1986–1987)—just in time for Catwoman to get a major reboot. Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli's “Batman: Year One” storyline in Batman #404–#407 (1987) reintroduced both the Dark Knight and the Feline Fatale. The product of a violent family, Selina Kyle and her sister were sent to a juvenile center after their mother's suicide. Selina ran away to live on the streets during her teens, surviving by any means possible, including prostitution. After witnessing the nascent Batman in action, Kyle was inspired by his disguise and adopted one of her own, donning a gray leather catsuit and whip and becoming the burglar Catwoman, preying upon Gotham's social elite. A 1989 four-issue Catwoman miniseries followed. Cinema once again made Catwoman a household name in 1992 in director Tim Burton's Batman Returns. Michelle Pfeiffer portrayed Selina Kyle, a mega-abused headcase who found liberation in death, being reanimated by alleycats that imbued her with a mystical feline spirit and catlike reflexes. Annette Bening was originally cast in the role but dropped out after becoming pregnant, and actress Sean Young, dressed in a cat-costume, made a muchpublicized but unsuccessful lobby for the part. Pfeiffer stole the picture in her body-hugging black catsuit, relishing in Catwoman's propensity for toying with her male opponents (after sucker-punching Batman by feigning feminine weakness, she gloated, “I'm a woman and can't be taken for granted. Life's a bitch, now so am I!”). Pfeiffer's Catwoman was softened for kidfriendly television as the Princess of Plunder, in a gray cat-costume and voiced by Adrienne Barbeau, was a recurring character in the acclaimed Batman: The Animated Series (1992–1995) and its continuation The Adventures of Batman & Robin (1997–1999). Throughout the 1990s, there was no shortage of Catwoman merchandising, based upon the Pfeiffer, animated, and comic-book interpretations of the character, from action figures marketed to boys to dolls and purses targeting girls. DC Comics awarded Catwoman her own monthly series, Catwoman vol. 2, which ran 94 issues between 1993 and 2001. She also costarred in a 1997 crossover with Vampirella and a 1998 miniseries with DC superhero Wildcat, who taught her boxing skills. Mere months after the cancellation of her series, DC's monthly Catwoman vol. 3 was launched with a January 2002 cover date. Catwoman has returned to her black catsuit, albeit with goggles that resemble large cat eyes; her ensemble is also loaded with combative and wallscaling gear including retractable claws and springaction boot pistons. In her two monthly comics series, as well as a number of spin-off miniseries and the 2002 graphic novel Catwoman: Selina's Big Score (by Darwyn Cooke), Catwoman has become a contemporary Robin Hood. She protects the downtrodden in Gotham's poverty-ridden East End, working with private eye Slam Bradley (a onetime paramour) and Dr. Leslie Thompkins to aid the needy that fall under the radar of police protection. She has become an ally of Batman, and the sexual tension between Cat and Bat continues, although the Dark Knight knows that despite her newfound heroism, this girl's eye can sometimes be distracted by a bright, shiny plaything. Catwoman remains adept at playing both sides: in a 2005 Catwoman story arc, she allied with supervillains including the Cheetah, Hush, and Captain Cold to destroy from the inside their aspirations to control the East End. A Batman Returns spin-off Catwoman film languished in development for years but finally made it to the screen in 2004. Michelle Pfeiffer turned down the chance to reprise her role; Ashley Judd was at first considered to play Catwoman (as was, reportedly, Nicole Kidman), but Oscar-winner Halle Berry was tapped for the tights. Catwoman built upon Batman Returns continuity by establishing that a cult of Catwomen had existed for eons (Pfeiffer's Kyle was one). After Berry's character, sheepish advertising artist Patience Phillips, took a fatal spill, she was “breathed” back to life by felines; as Catwoman, she tangled with femme fatale Laurel Hedare (Sharon Stone), a catty businesswoman whose age-defying beauty product had sinister side effects. Catwoman suffered from a crippling prerelease backlash from comic-book fans that rejected Berry's streetwalker-like costume (with its abnormally large, helmet-sized catcowl) and the movie's deviation from comic-book mythology. Filmed for an estimated $85 million, Catwoman limped through an embarrassing $16 million opening weekend and a total U.S. gross of $40 million. While the film died at the box office, remember, Catwoman has eight more lives. She strutted onto the tube again in the WB's animated The Batman (2004–present), with Gina Gershon playing the part, and continues to tantalize comic-book readers and toy collectors.

The Supervillain Book: The Evil Side of Comics and Hollywood © 2006 Visible Ink Press®. All rights reserved.