In Baum, S. M., Reis, S. M., & Maxfield, L. R. (Eds.). (1998). Nurturing the gifts and talents of primary grade students. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Joseph S. Renzulli, Ed.D.

Director

The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented

University of Connecticut

Storrs, Connecticut

The age-old issue of “what makes giftedness” has been debated by scholars for decades. In the past twenty years, a renewed interest has emerged on this topic. This chapter will attempt to shed some light on this complex and controversial question by describing a broad range of theoretical issues and research studies that have been associated with the study of gifted and talented persons. Although the information reported here draws heavily on the theoretical and research literature, it is clearly written from the point of view of an educational practitioner who respects both theory and research, but who also has devoted a major amount of his efforts to translating these types of information into what he believes to be defensible identification and programming practices. Those in the position of offering advice to school systems that are faced with the reality of identifying and serving highly able students must also provide the types of underlying research that lend credibility to their advice. Accordingly, this chapter might be considered a theoretical and research rationale for a separate publication that describes a plan for identifying and programming for gifted and talented students (Renzulli, 1994; Renzulli & Reis, 1985).

This chapter is divided into three sections. The first section deals with several major issues that might best be described as the enduring questions and sources of controversy in a search for the meaning of giftedness and related attempts to define this concept. It is hoped that a discussion of these issues will establish common points of understanding between the writer and the reader and, at the same time, point out certain biases that are unavoidable whenever one deals with a complex and value-laden topic.

The second section describes a wide range of research studies that support the writer’s “three-ring” conception of giftedness. This section concludes with an explicit definition and a brief review of research studies that have been carried out in school programs using an identification system based on the three-ring concept. The final section examines a number of questions raised by scholars and practitioners since the original publication (Renzulli, 1978) of this particular approach.

Section I: Issues in the Study of Conceptions of Giftedness

Purposes and Criteria for a Definition of Giftedness

One of the first and most important issues that should be dealt with in a search for the meaning of giftedness is that there must be a purpose for defining this concept. The goals of science tell us that a primary purpose is to add new knowledge to our understanding about human conditions, but in an applied field of knowledge there is also a practical purpose for defining concepts. Persons who presume to be the writers of definitions should understand the full ramifications of these purposes and recognize the practical and political uses to which their work might be applied. A definition of giftedness is a formal and explicit statement that might eventually become part of official policies or guidelines. Whether or not it is the writer’s intent, such statements will undoubtedly be used to direct identification and programming practices, and therefore we must recognize the consequential nature of this purpose and the pivotal role that definitions play in structuring the entire field. Definitions are open to both scholarly and practical scrutiny, and for these reasons it is important that a definition meet the following criteria:

- It must be based on the best available research about the characteristics of gifted individuals rather than romanticized notions or unsupported opinions.

- It must provide guidance in the selection and/or development of instruments and procedures that can be used to design defensible identification systems.

- It must give direction, and be logically related to programming practices such as the selection of materials and instructional methods, the selection and training of teachers and the determination of procedures whereby programs can be evaluated.

- It must be capable of generating research studies that will verify or fail to verify the validity of the definition.

In view of the practical purposes for which a definition might be used, it is necessary to consider any definition in the larger context of overall programming for the target population we are attempting to serve. In other words, the way in which one views giftedness will be a primary factor in both constructing a plan for identification and in providing services that are relevant to the characteristics that brought certain youngsters to our attention in the first place. If, for example, one identifies giftedness as extremely high mathematical aptitude, then it would seem nothing short of common sense to use assessment procedures that readily identify potential for superior performance in this particular area of ability. And it would be equally reasonable to assume that a program based on this definition and identification procedure should devote major emphasis to the enhancement of performance in mathematics and related areas. Similarly, a definition that emphasizes artistic abilities should point the way toward relatively specific identification and programming practices. As long as there are differences of opinion among reasonable scholars there will never be a single definition of giftedness, and this is probably the way that it should be. But one requirement for which all writers of definitions should be accountable is the necessity of showing a logical relationship between definition on the one hand and recommended identification and programming practices on the other.

Two Kinds of Giftedness

A second issue that must be dealt with is that our present efforts to define giftedness are based on a long history of previous studies dealing with human abilities. Most of these studies focused mainly on the concept of intelligence and are briefly discussed here to establish an important point about the process of defining concepts rather than any attempt to equate intelligence with giftedness. Although a detailed review of these studies is beyond the scope of the present chapter, a few of the general conclusions from earlier research are necessary to set the stage for this analysis.1

The first conclusion is that intelligence is not a unitary concept, but rather there are many kinds of intelligence and therefore single definitions cannot be used to explain this complicated concept. The confusion and inconclusiveness about present theories of intelligence has led Sternberg (1984) and others to develop new models for explaining this complicated concept. Sternberg’s “triarchic” theory of human intelligence consists of three subtheories: a contextual subtheory, which relates intelligence to the external world of the individual; a two-facet subtheory, which relates intelligence to both the external and internal worlds of the individual; and a componential subtheory, which relates intelligence to the internal world of the individual. The contextual subtheory defines intelligent behavior in terms of purposive adaptation to, selection of, and shaping of real-world environments relevant to one’s life. The two-facet subtheory further constrains this definition by regarding as most relevant to the demonstration of intelligence contextually intelligent behavior that involves either adaptation to novelty or automatization of information processing, or both. The componential subtheory specifies the mental mechanisms responsible for the learning, planning, execution, and evaluation of intelligent behavior. Sternberg explains the interaction among the three subtheories by offering the following examples:

The first individual might come across to people as smart but not terribly creative; the second individual might come across to people as creative but not terribly smart. Although it might well be possible to obtain some average score on componential abilities and abilities to deal with nonentrenched tasks and situations, such a composite would obscure the critical qualitative differences between the functioning of the two individuals. Or consider a person who is both componentially adept and insightful, but who makes little effort to fit into the environment in which he or she lives. Certainly one would not want to take some overall average that hides the person’s academic intelligence (or even brilliance) in a combined index that is reduced because of reduced adaptive skills. The point to be made, then, is that intelligence is not a single thing: It comprises a very wide array of cognitive and other skills. Our goal in theory, research, and measurement ought to be to define what these skills are and learn how best to assess and possibly train them, not to figure out a way to combine them into a single, but possibly meaningless number. (pp. 62–63)

In view of this recent work and numerous earlier cautions about the dangers of trying to describe intelligence through the use of single scores, it seems safe to conclude that this practice has been and always will be questionable. At the very least, attributes of intelligent behavior must be considered within the context of cultural and situational factors. Indeed, some of the most recent examinations have concluded that “[t]he concept of intelligence cannot be explicitly defined, not only because of the nature of intelligence but also because of the nature of concepts” (Neisser, 1979, p. 179).

A second conclusion is that there is no ideal way to measure intelligence and therefore we must avoid the typical practice of believing that if we know a person’s IQ score, we also know his or her intelligence. Even Terman warned against total reliance on tests: “We must guard against defining intelligence solely in terms of ability to pass the tests of a given intelligence scale” (1926, p. 131). E. L. Thorndike echoed Terman’s concern by stating “to assume that we have measured some general power which resides in [the person being tested] and determines his ability in every variety of intellectual task in its entirety is to fly directly in the face of all that is known about the organization of the intellect” (Thorndike, 1921, p. 126).

The reason I have cited these concerns about the historical difficulty of defining and measuring intelligence is to highlight the even larger problem of isolating a unitary definition of giftedness. At the very least we will always have several conceptions (and therefore definitions) of giftedness; but it will help in this analysis to begin by examining two broad categories that have been dealt with in the research literature. I will refer to the first category as schoolhouse giftedness” and to the second as creative-productive giftedness.” Before going on to describe each type, I want to emphasize that:

- Both types are important.

- There is usually an interaction between the two types.

- Special programs should make appropriate provisions for encouraging both types of giftedness as well as the numerous occasions when the two types interact with each other.

Schoolhouse Giftedness

Schoolhouse giftedness might also be called test-taking or lesson-learning giftedness. It is the kind most easily measured by IQ or other cognitive ability tests, and for this reason it is also the type most often used for selecting students for entrance into special programs. The abilities people display on IQ and aptitude tests are exactly the kinds of abilities most valued in traditional school learning situations. In other words, the games people play on ability tests are similar in nature to games that teachers require in most lesson-learning situations. Research tells us that students who score high on IQ tests are also likely to get high grades in school. Research also has shown that these test-taking and lesson-learning abilities generally remain stable over time. The results of this research should lead us to some very obvious conclusions about schoolhouse giftedness: it exists in varying degrees; it can be identified through standardized assessment techniques; and we should therefore do everything in our power to make appropriate modifications for students who have the ability to cover regular curricular material at advanced rates and levels of understanding. Curriculum compacting (Renzulli, Smith, & Reis, 1982), a procedure used for modifying curricular content to accommodate advanced learners, and other acceleration techniques should represent an essential part of any school program that strives to respect the individual differences that are clearly evident from scores yielded by cognitive ability tests.

Although there is a generally positive correlation between IQ scores and school grades, we should not conclude that test scores are the only factors that contribute to success in school. Because IQ scores correlate only from .40 to .60 with school grades, they account for only 16–36% of the variance in these indicators of potential. Many youngsters who are moderately below the traditional 3–5% test score cutoff levels for entrance into gifted programs clearly have shown that they can do advanced-level work. Indeed, most of the students in the nation’s major universities and 4-year colleges come from the top 20% of the general population (rather than just the top 3–5%) and Jones (1982) reported that a majority of college graduates in every scientific field of study had IQs between 110 and 120. Are we “making sense” when we exclude such students from access to special services? To deny them this opportunity would be analogous to forbidding a youngster from trying out for a basketball team because he or she missed a predetermined “cutoff height” by a few inches! Basketball coaches are not foolish enough to establish inflexible cutoff heights because they know that such an arbitrary practice would cause them to overlook the talents of youngsters who may overcome slight limitations in inches with other abilities such as drive, speed, teamwork, ball-handling skills, and perhaps even the ability and motivation to outjump taller persons who are trying out for the team. As educators of gifted and talented youth, we can undoubtedly take a few lessons about flexibility from coaches!

Creative-Productive Giftedness

If scores on IQ tests and other measures of cognitive ability only account for a limited proportion of the common variance with school grades, we can be equally certain that these measures do not tell the whole story when it comes to making predictions about creative-productive giftedness. Before defending this assertion with some research findings, let us briefly review what is meant by this second type of giftedness, the important role that it should play in programming, and, therefore, the reasons we should attempt to assess it in our identification procedures—even if such assessment causes us to look below the top 3–5% on the normal curve of IQ scores.

Creative-productive giftedness describes those aspects of human activity and involvement where a premium is placed on the development of original material and products that are purposefully designed to have an impact on one or more target audiences. Learning situations that are designed to promote creative-productive giftedness emphasize the use and application of information (content) and thinking processes in an integrated, inductive, and real-problem-oriented manner. The role of the student is transformed from that of a learner of prescribed lessons to one in which she or he uses the modus operandi of a firsthand inquirer. This approach is quite different from the development of lesson-learning giftedness that tends to emphasize deductive learning; structured training in the development of thinking processes; and the acquisition, storage, and retrieval of information. In other words, creative-productive giftedness is simply putting one’s abilities to work on problems and areas of study that have personal relevance to the student and that can be escalated to appropriately challenging levels of investigative activity. The roles that both students and teachers should play in the pursuit of these problems have been described elsewhere (Renzulli, 1982, 1983).

Why is creative-productive giftedness important enough for us to question the “tidy” and relatively easy approach that traditionally has been used to select students on the basis of test scores? Why do some people want to rock the boat by challenging a conception of giftedness that can be numerically defined by simply giving a test? The answers to these questions are simple and yet very compelling. The research reviewed in the second section of this chapter tells us that there is much more to the making of a gifted person than the abilities revealed on traditional tests of intelligence, aptitude, and achievement. Furthermore, history tells us it has been the creative and productive people of the world, the producers rather than consumers of knowledge, the reconstructionists of thought in all areas of human endeavor, who have become recognized as “truly gifted” individuals. History does not remember persons who merely scored well on IQ tests or those who learned their lessons well.

The Purposes of Education for the Gifted

Implicit in any efforts to define and identify gifted youth is the assumption that we will “do something” to provide various types of specialized learning experiences that show promise of promoting the development of characteristics implicit in the definition. In other words, the why question supersedes the who and how questions. Although there are two generally accepted purposes for providing special education for the gifted, I believe that these two purposes in combination give rise to a third purpose that is intimately related to the definition question.

The first purpose of gifted education2 is to provide young people with maximum opportunities for self-fulfillment through the development and expression of one or a combination of performance areas where superior potential may be present.

The second purpose is to increase society’s supply of persons who will help to solve the problems of contemporary civilization by becoming producers of knowledge and art rather than mere consumers of existing information. Although there may be some arguments for and against both of the above purposes, most people would agree that goals related to self-fulfillment and/or societal contributions are generally consistent with democratic philosophies of education. What is even more important is that the two goals are highly interactive and mutually supportive of each other. In other words, the self-satisfying work of scientists, artists, and leaders in all walks of life usually produces results that might be valuable contributions to society. Carrying this point one step further, we might even conclude that appropriate kinds of learning experiences can and should be engineered to achieve the twofold goals described above. Keeping in mind the interaction of these two goals, and the priority status of the self-fulfillment goal, it is safe to conclude that supplementary investments of public funds and systematic effort for highly able youth should be expected to produce at least some results geared toward the public good. If, as Gowan (1978) has pointed out, the purpose of gifted programs is to increase the size of society’s reservoir of potentially creative and productive adults, then the argument for gifted education programs that focus on creative productivity (rather than lesson-learning giftedness) is a very simple one. If we agree with the goals of gifted education set forth earlier in the article, and if we believe that our programs should produce the next generation of leaders, problem solvers, and persons who will make important contributions to the arts and sciences, then does it not make good sense to model our training programs after the modus operandi of these persons rather than after those of the lesson learner?

This is especially true because research (as described later in the chapter) tells us that the most efficient lesson learners are not necessarily those persons who go on to make important contributions in the realm of creative productivity. And in this day and age, when knowledge is expanding at almost geometric proportions, it would seem wise to consider a model that focuses on how our most able students access and make use of information rather than merely on how they accumulate and store it.

The Gifted and the Potentially Gifted

A further issue relates to the subtle but very important distinction that exists between the “gifted” and the “potentially gifted.” Most of the research reviewed in the second section of this chapter deals with student and adult populations whose members have been judged (by one or more criteria) to be gifted. In most cases, researchers have studied those who have been identified as “being gifted” much more intensively than they have studied persons who were not recognized or selected because of unusual accomplishments. The general approach to the study of gifted persons could easily lead the casual reader to believe that giftedness is a condition that is magically bestowed on a person in much the same way that nature endows us with blue eyes, red hair, or a dark complexion. This position is not supported by the research. Rather, what the research clearly and unequivocally tells us is that giftedness can be developed in some people if an appropriate interaction takes place between a person, his or her environment, and a particular area of human endeavor.

It should be kept in mind that when I describe, in the paragraphs that follow, a certain trait as being a component of giftedness (for example, creativity), I am in no way assuming that one is “born with” this trait, even if one happens to possess a high IQ. Almost all human abilities can be developed, and therefore my intent is to call attention to the potentially gifted (that is to say, those who could “make it” under the right conditions) as well as to those who have been studied because they gained some type of recognition. Implicit in this concept of the potentially gifted, then, is the idea that giftedness emerges or “comes out” at different times and under different circumstances. Without such an approach there would be no hope whatsoever of identifying bright underachievers, students from disadvantaged backgrounds, or any other special population that is not easily identified through traditional testing procedures.

Are People “Gifted” or Do They Display Gifted Behaviors?

A fifth and final issue underlying the search for a definition of giftedness is more nearly a bias and a hope for at least one major change in the ways we view this area of study. Except for certain functional purposes related mainly to professional focal points (i.e., research, training, legislation) and to ease of expression, I believe that a term such as the gifted is counterproductive to educational efforts aimed at identification and programming for certain students in the general school population. Rather, it is my hope that in years ahead we will shift our emphasis from the present concept of “being gifted” (or not being gifted) to a concern about developing gifted behaviors in those youngsters who have the highest potential for benefiting from special education services. This slight shift in terminology might appear to be an exercise in heuristic hairsplitting, but I believe that it has significant implications for the entire way we think about the concept of giftedness and the ways in which we structure the field for important research endeavors3 and effective educational programming.

For too many years we have pretended that we can identify gifted children in an absolute and unequivocal fashion. Many people have been led to believe that certain individuals have been endowed with a golden chromosome that makes them “gifted persons.” This belief has further led to the mistaken idea that all we need to do is find the right combination of factors that prove the existence of this chromosome. The further use of such terms as the “truly gifted,” the “moderately gifted,” and the “borderline gifted” only serve to confound the issue and might result in further misguided searches for silver and bronze chromosomes. This misuse of the concept of giftedness has given rise to a great deal of confusion and controversy about both identification and programming, and the result has been needless squabbling among professionals in the field. Another result has been that so many mixed messages have been sent to educators and the public at large that both groups now have a justifiable skepticism about the credibility of the gifted education establishment and our ability to offer services that are qualitatively different from general education.

Most of the confusion and controversy surrounding the definition of giftedness can be placed in proper perspective by raising a series of questions that strike right at the heart of key issues related to this area of study. These questions are organized into the following clusters:

- Are giftedness and high IQ one and the same? And if so, how high does one’s IQ need to be before he or she can be considered gifted? If giftedness and high IQ are not the same, what are some of the other characteristics that contribute to the expression of giftedness? Is there any justification for providing selective services for certain students who may fall below a predetermined IQ cutoff score?

- Is giftedness an absolute or a relative concept? That is, is a person either gifted or not gifted (the absolute view) or can varying kinds and degrees of gifted behaviors be displayed in certain people, at certain times, and under certain circumstances (the relative view)? Is giftedness a static concept (i.e., you have it or you don’t have it) or is it a dynamic concept (i.e., it varies both within persons and within learning-performance situations)?

- What causes only a minuscule number of Thomas Edisons or Langston Hugheses or Isadora Duncans to emerge, whereas millions of others with equal “equipment” and educational advantages (or disadvantages) never rise above mediocrity? Why do some people who have not enjoyed the advantages of special educational opportunities achieve high levels of accomplishment, whereas others who have gone through the best of educational programming opportunities fade into obscurity?

In the section that follows, a series of research studies will be reviewed in an effort to answer these questions. Taken collectively, these research studies are the most powerful argument that can be put forth to policymakers who must render important decisions about the regulations and guidelines that will dictate identification practices in their states or local school districts. An examination of this research clearly tells us that gifted behaviors can be developed in those who are not necessarily individuals who earn the highest scores on standardized tests. The two major implications of this research for identification practices are equally clear.

First, an effective identification system must take into consideration other factors in addition to test scores. Recent research has shown that, in spite of the multiple criterion information gathered in many screening procedures, rigid cutoff scores on IQ or achievement tests are still the main if not the only criterion given serious consideration in final selection (Alvino, 1981). When screening information reveals outstanding potential for gifted behaviors, it is almost always “thrown away” if predetermined cutoff scores are not met. Respect for these other factors means that they must be given equal weight and that we can no longer merely give lip service to nontest criteria; nor can we believe that because tests yield “numbers” they are inherently more valid and objective than other procedures. As Sternberg (1982a) has pointed out, quantitative does not necessarily mean valid. When it comes to identification, it is far better to have imprecise answers to the right questions than precise answers to the wrong questions.

The second research-based implication will undoubtedly be a major controversy in the field for many years, but it needs to be dealt with if we are ever going to defuse a majority of the criticism that has been justifiably directed at our field. Simply stated, we must reexamine identification procedures that result in a total preselection of certain students and the concomitant implication that these young people are and always will be “gifted.” This absolute approach (i.e., you have it or you don’t have it) coupled with the almost total reliance on test scores is not only inconsistent with what the research tells us, but almost arrogant in the assumption that we can use a single one-hour segment of a young person’s total being to determine if he or she is “gifted.”

The alternative to such an absolutist view is that we may have to forgo the “tidy” and comfortable tradition of “knowing” on the first day of school who is gifted and who is not gifted. Rather, our orientation must be redirected toward developing “gifted behaviors” in certain students (not all students), at certain times (not all the time), and under certain circumstances. The trade-off for tidiness and administrative expediency will result in a much more flexible approach to both identification and programming and a system that not only shows a greater respect for the research on gifted and talented people, but one that is both fairer and more acceptable to other educators and to the general public.

Section II: Research Underlying the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness

One way of analyzing the research underlying conceptions of giftedness is to review existing definitions along a continuum ranging from conservative to liberal. Conservative and liberal are used here not in their political connotations, but rather according to the degree of restrictiveness that is used in determining who is eligible for special programs and services.

Restrictiveness can be expressed in two ways. First, a definition can limit the number of specific performance areas that are considered in determining eligibility for special programs. A conservative definition, for example, might limit eligibility to academic performance only and exclude other areas such as music, art, drama, leadership, public speaking, social service, and creative writing. Second, a definition can limit the degree or level of excellence that one must attain by establishing extremely high cutoff points.

At the conservative end of the continuum is Terman’s (1926) definition of giftedness as “the top 1 percent level in general intellectual ability as measured by the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale or a comparable instrument” (p. 43). In this definition, restrictiveness is present in terms of both the type of performance specified (i.e., how well one scores on an intelligence test) and the level of performance one must attain to be considered gifted (top 1%). At the other end of the continuum can be found more liberal definitions, such as the following one by Witty (1958):

There are children whose outstanding potentialities in art, in writing, or in social leadership can be recognized largely by their performance. Hence, we have recommended that the definition of giftedness be expanded and that we consider any child gifted whose performance, in a potentially valuable line of human activity, is consistently remarkable. (p. 62)

Although liberal definitions have the obvious advantage of expanding the conception of giftedness, they also open up two “cans of worms” by introducing a values issue (What are the potentially valuable lines of human activity?) and the age-old problem of subjectivity in measurement.

In recent years the values issue has been largely resolved. There are very few educators who cling tenaciously to a “straight IQ” or purely academic definition of giftedness. “Multiple talent” and “multiple criteria” are almost the bywords of the present-day gifted student movement, and most persons would have little difficulty in accepting a definition that includes almost every area of human activity that manifests itself in a socially useful form of expression.

The problem of subjectivity in measurement is not as easily resolved. As the definition of giftedness is extended beyond those abilities that are clearly reflected in tests of intelligence, achievement, and academic aptitude, it becomes necessary to put less emphasis on precise estimates of performance and potential and more emphasis on the opinions of qualified human judges in making decisions about admission to special programs. The crux of the issue boils down to a simple and yet very important question: How much of a trade-off are we willing to make on the objective-subjective continuum in order to allow recognition of a broader spectrum of human abilities? If some degree of subjectivity cannot be tolerated, then our definition of giftedness and the resulting programs will logically be limited to abilities that can be measured only by objective tests.

The Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness

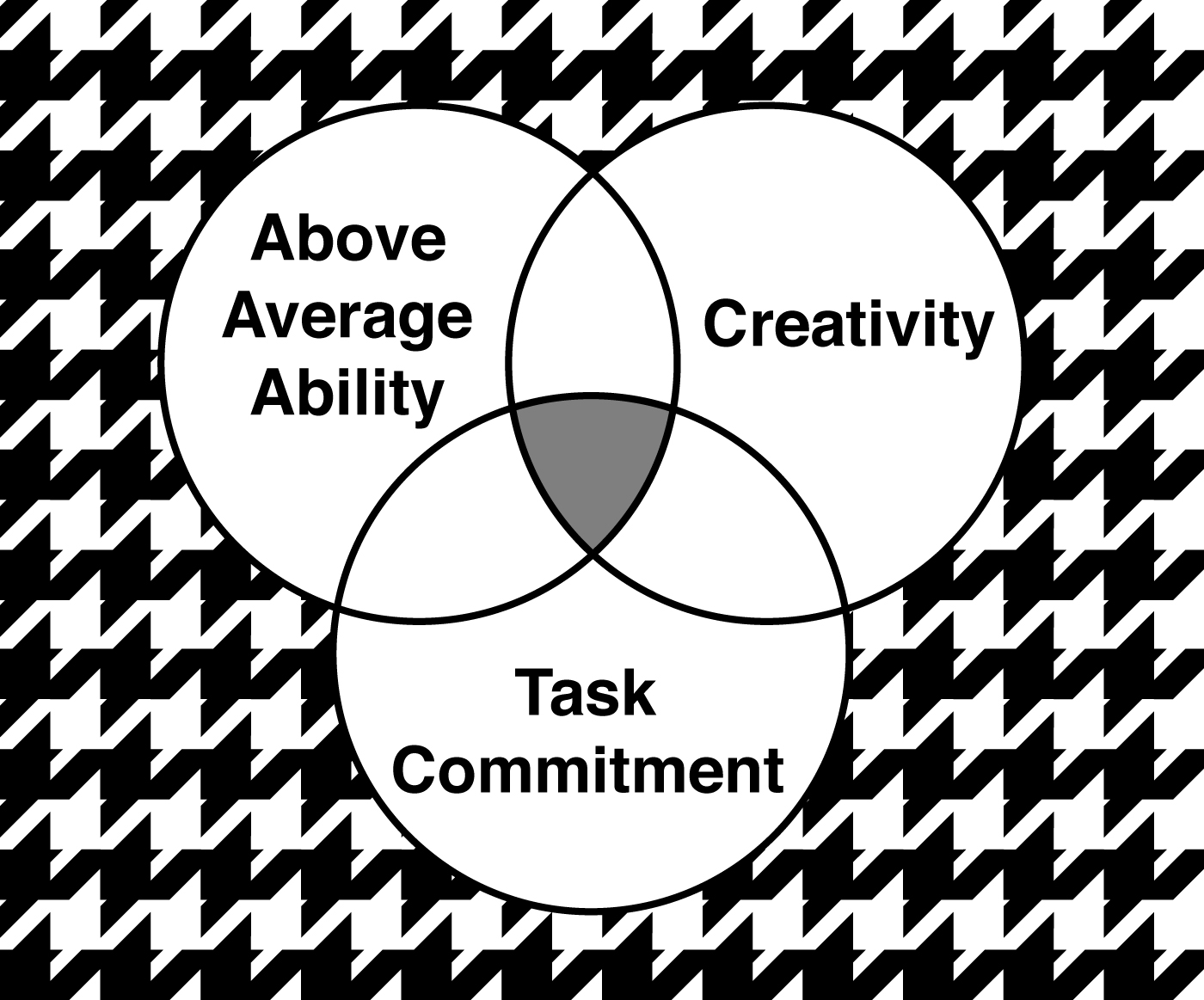

Research on creative-productive people has consistently shown that although no single criterion can be used to determine giftedness, persons who have achieved recognition because of their unique accomplishments and creative contributions possess a relatively well-defined set of three interlocking clusters of traits. These clusters consist of above average, though not necessarily superior, ability, task commitment, and creativity (see Figure 1). It is important to point out that no single cluster “makes giftedness.” Rather, it is the interaction among the three clusters that research has shown to be the necessary ingredient for creative-productive accomplishment (Renzulli, 1978). This interaction is represented by the shaded portion of Figure 1. It is also important to point out that each cluster plays an important role in contributing to the display of gifted behaviors. This point is emphasized because one of the major errors that continues to be made in identification procedures is to overemphasize superior abilities at the expense of the other two clusters of traits.

Figure 1. What makes giftedness.

Well Above Average Ability

Well above average ability can be defined in two ways—general ability and specific abilities.

General ability consists of the capacity to process information, to integrate experiences that result in appropriate and adaptive responses in new situations, and the capacity to engage in abstract thinking. Examples of general ability are verbal and numerical reasoning, spatial relations, memory, and word fluency. These abilities are usually measured by tests of general aptitude or intelligence, and are broadly applicable to a variety of traditional learning situations.

Specific abilities consist of the capacity to acquire knowledge, skill, or the ability to perform in one or more activities of a specialized kind and within a restricted range. These abilities are defined in a manner that represents the ways in which human beings express themselves in real-life (i.e., nontest) situations. Examples of specific abilities are chemistry, ballet, mathematics, musical composition, sculpture, and photography. Each specific ability can be further subdivided into even more specific areas (e.g., portrait photography, astrophotography, photo journalism). Specific abilities in certain areas such as mathematics and chemistry have a strong relationship with general ability and, therefore, some indication of potential in these areas can be determined from tests of general aptitude and intelligence. They can also be measured by achievement tests and tests of specific aptitude. Many specific abilities, however, cannot be easily measured by tests, and, therefore, areas such as the arts must be evaluated through one or more performance-based assessment techniques.

Within this model the term above average ability will be used to describe both general and specific abilities. Above average should also be interpreted to mean the upper range of potential within any given area. Although it is difficult to assign numerical values to many specific areas of ability, when I refer to “well above average ability” I clearly have in mind persons who are capable of performance or the potential for performance that is representative of the top 15–20% of any given area of human endeavor.

Although the influence of intelligence, as traditionally measured, quite obviously varies with specific areas of performance, many researchers have found that creative accomplishment is not necessarily a function of measured intelligence. In a review of several research studies dealing with the relationship between academic aptitude tests and professional achievement, Wallach (1976) concluded that: “Above intermediate score levels, academic skills assessments are found to show so little criterion validity as to be a questionable basis on which to make consequential decisions about students’ futures. What the academic tests do predict are the results a person will obtain on other tests of the same kind” (p. 57).

Wallach goes on to point out that academic test scores at the upper ranges—precisely the score levels that are most often used for selecting persons for entrance into special programs—do not necessarily reflect the potential for creative-productive accomplishment. Wallach suggests that test scores be used to screen out persons who score in the lower ranges and that beyond this point decisions should be based on other indicators of potential for superior performance.

Numerous research studies support Wallach’s findings that there is a limited relationship between test scores and school grades on the one hand, and real-world accomplishments on the other (Bloom, 1963; Harmon, 1963; Helson & Crutchfield, 1970; Hudson, 1960; Mednick, 1963; Parloff, Datta, Kleman, & Handlon, 1968; Richards, Holland, & Lutz, 1967; Wallach & Wing, 1969). In fact, in a study dealing with the prediction of various dimensions of achievement among college students, Holland and Astin (1962) found that:

Getting good grades in college has little connection with more remote and more socially relevant kinds of achievement; indeed, in some colleges, the higher the student’s grades, the less likely it is that he is a person with creative potential. So it seems desirable to extend our criteria of talented performance. (pp. 132–133)

A study by the American College Testing Program (Munday & Davis, 1974) entitled, “Varieties of Accomplishment After College: Perspectives on the Meaning of Academic Talent,” concluded that:

. . . [the] adult accomplishments were found to be uncorrelated with academic talent, including test scores, high school grades, and college grades. However, the adult accomplishments were related to comparable high school nonacademic (extra-curricular) accomplishments. This suggests that there are many kinds of talents related to later success which might be identified and nurtured by educational institutions. (p. 2)

The pervasiveness of this general finding is demonstrated by Hoyt (1965), who reviewed 46 studies dealing with the relationship between traditional indications of academic success and postcollege performance in the fields of business, teaching, engineering, medicine, scientific research, and other areas such as the ministry, journalism, government, and miscellaneous professions. From this extensive review, Hoyt concluded that traditional indications of academic success have no more than a very modest correlation with various indicators of success in the adult world and that “There is good reason to believe that academic achievement (knowledge) and other types of educational growth and development are relatively independent of each other” (p. 73).

The recent experimental studies conducted by Sternberg (1981) and Sternberg and Davidson (1982) have added a new dimension to our understanding about the role that intelligence tests should play in making identification decisions. After numerous investigations into the relationship between traditionally measured intelligence and other factors, such as problem solving and insightful solutions to complex problems, Sternberg (1982b) concluded that:

Tests only work for some of the people some of the time—not for all of the people all of the time—and that some of the assumptions we make in our use of tests are, at best, correct only for a segment of the tested population, and at worst, correct for none of it. As a result we fail to identify many gifted individuals for whom the assumptions underlying our use of tests are particularly inadequate. The problem, then, is not only that tests are of limited validity for everyone, but that their validity varies across individuals. For some people, tests scores may be quite informative, for others such scores may be worse than useless. Use of test score cutoffs and formulas results in a serious problem of underidentification of gifted children. (p. 157)

The studies raise some basic questions about the use of tests as a major criterion for making selection decisions. The research reported above clearly indicates that vast numbers and proportions of our most productive persons are not those who scored at the 95th percentile or above on standardized tests of intelligence, nor were they necessarily straight A students who discovered early how to play the lesson-learning game. In other words, more creative-productive persons came from below the 95th percentile than above it, and if such cutoff scores are needed to determine entrance into special programs, we may be guilty of actually discriminating against persons who have the greatest potential for high levels of accomplishment.

The most defensible conclusion about the use of intelligence tests that can be put forward at this time is based on research findings dealing with the “threshold effect.” Reviews by Chambers (1969) and Stein (1968) and research by Walberg (1969, 1971) indicate that accomplishments in various fields require minimal levels of intelligence, but that beyond these levels, degrees of attainment are weakly associated with intelligence. In studies of creativity it is generally acknowledged that a fairly high though not exceptional level of intelligence is necessary for high degrees of creative achievement (Barron, 1969; Campbell, 1960; Guilford, 1964, 1967; McNemar, 1964; Vernon, 1967).

Research on the threshold effect indicates that different fields and subject matter areas require varying degrees of intelligence for high-level accomplishment. In mathematics and physics the correlation of measured intelligence with originality in problem solving tends to be positive, but quite low. Correlations between intelligence and the rated quality of work by painters, sculptors, and designers is zero or slightly negative (Barron, 1968). Although it is difficult to determine exactly how much measured intelligence is necessary for high levels of creative and productive accomplishment within any given field, there is a consensus among many researchers (Barron, 1969; Bloom, 1963; Cox, 1926; Harmon, 1963; Helson & Crutchfield, 1970; MacKinnon, 1962, 1965; Oden, 1968; Roe, 1952; Terman, 1954) that once the IQ is 120 or higher other variables become increasingly important. These variables are discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

Task Commitment

A second cluster of traits that consistently has been found in creative-productive persons is a refined or focused form of motivation known as task commitment. Whereas motivation is usually defined in terms of a general energizing process that triggers responses in organisms, task commitment represents energy brought to bear on a particular problem (task) or specific performance area. The terms that are most frequently used to describe task commitment are perseverance, endurance, hard work, dedicated practice, self-confidence, and a belief in one’s ability to carry out important work. In addition to perceptiveness (Albert, 1975) and a better sense for identifying significant problems (Zuckerman, 1979), research on persons of unusual accomplishment has consistently shown that a special fascination for and involvement with the subject matter of one’s chosen field “are the almost invariable precursors of original and distinctive work” (Barron, 1969, p. 3). Even in young people whom Bloom and Sosniak (1981) identified as extreme cases of talent development, early evidence of task commitment was present. Bloom and Sosniak report that “after age 12 our talented individuals spent as much time on their talent field each week as their average peer spent watching television” (p. 94).

The argument for including this nonintellective cluster of traits in a definition of giftedness is nothing short of overwhelming. From popular maxims and autobiographical accounts to hard-core research findings, one of the key ingredients that has characterized the work of gifted persons is their ability to involve themselves totally in a specific problem or area for an extended period of time.

The legacy of both Sir Francis Galton and Lewis Terman clearly indicates that task commitment is an important part of the making of a gifted person. Although Galton was a strong proponent of the hereditary basis for what he called “natural ability,” he nevertheless subscribed heavily to the belief that hard work was part and parcel of giftedness:

By natural ability, I mean those qualities of intellect and disposition, which urge and qualify a man to perform acts that lead to reputation. I do not mean capacity without zeal, nor zeal without capacity, nor even a combination of both of them, without an adequate power of doing a great deal of very laborious work. But I mean a nature which, when left to itself, will, urged by an inherent stimulus, climb the path that leads to eminence and has strength to reach the summit—on which, if hindered or thwarted, will fret and strive until the hindrance is overcome, and it is again free to follow its laboring instinct. (Galton, 1869, p. 33, as quoted in Albert, 1975, p. 142)

The monumental studies of Lewis Terman undoubtedly represent the most widely recognized and frequently quoted research on the characteristics of gifted persons. Terman’s studies, however, have unintentionally left a mixed legacy because most persons have dwelt (and continue to dwell) on “early Terman” rather than the conclusions he reached after several decades of intensive research. As such, it is important to consider the following conclusion that he reached as a result of 30 years of follow-up studies on his initial population:

The results [of the follow-up] indicated that personality factors are extremely important determiners of achievement . . . . The four traits on which [the most and least successful groups] differed most widely were persistence in the accomplishment of ends, integration toward goals, self-confidence, and freedom from inferiority feelings. In the total picture the greatest contrast between the two groups was in all-round emotional and social adjustment, and in drive to achieve. (Terman, 1959, p. 148; italics added)

Although Terman never suggested that task commitment should replace intelligence in our conception of giftedness, he did state that “intellect and achievement are far from perfectly correlated.”

Several more recent research studies support the findings of Galton and Terman and have shown that creative-productive persons are far more task oriented and involved in their work than are people in the general population. Perhaps the best known of these studies is the work of Roe (1952) and MacKinnon (1964, 1965). Roe conducted an intensive study of the characteristics of 64 eminent scientists and found that all of her subjects had a high level of commitment to their work. MacKinnon pointed out traits that were important in creative accomplishments: “It is clear that creative architects more often stress their inventiveness, independence and individuality, their enthusiasm, determination, and industry” (1964, p. 365; italics added).

Extensive reviews of research carried out by Nicholls (1972) and McCurdy (1960) found patterns of characteristics that were consistently similar to the findings reported by Roe and MacKinnon. Although the studies cited thus far used different research procedures and dealt with a variety of populations, there is a striking similarity in their major conclusions. First, academic ability (as traditionally measured by tests or grade point averages) showed limited relationships to creative-productive accomplishment. Second, nonintellectual factors, and especially those related to task commitment, consistently played an important part in the cluster of traits that characterized highly productive people. Although this second cluster of traits is not as easily and objectively identifiable as general cognitive abilities are, these traits are nevertheless a major component of giftedness and should, therefore, be reflected in our definition.

Creativity

The third cluster of traits that characterizes gifted persons consists of factors usually lumped together under the general heading of creativity.” As one reviews the literature in this area, it becomes readily apparent that the words gifted, genius, and eminent creators or highly creative persons are used synonymously. In many of the research projects discussed above, the persons ultimately selected for intensive study were in fact recognized because of their creative accomplishments. In MacKinnon’s (1964) study, for example, panels of qualified judges (professors of architecture and editors of major American architectural journals) were asked first to nominate and later to rate an initial pool of nominees, using the following dimensions of creativity:

- Originality of thinking and freshness of approaches to architectural problems.

- Constructive ingenuity.

- Ability to set aside established conventions and procedures when appropriate.

- A flair for devising effective and original fulfillments of the major demands of architecture, namely, technology (firmness), visual form (delight), planning (commodity), and human awareness and social purpose. (p. 360)

When discussing creativity, it is important to consider the problems researchers have encountered in establishing relationships between creativity tests and other more substantial accomplishments. A major issue that has been raised by several investigators deals with whether or not tests of divergent thinking actually measure “true” creativity. Although some validation studies have reported limited relationships between measures of divergent thinking and creative performance criteria (Dellas & Gaier, 1970; Guilford, 1967; Shapiro, 1968; Torrance, 1969) the research evidence for the predictive validity of such tests has been limited. Unfortunately, very few tests have been validated against real-life criteria of creative accomplishment; however, future longitudinal studies using these relatively new instruments might show promise of establishing higher levels of predictive validity. Thus, although divergent thinking is indeed a characteristic of highly creative persons, caution should be exercised in the use and interpretation of tests designed to measure this capacity.

Given the inherent limitations of creativity tests, a number of writers have focused attention on alternative methods for assessing creativity. Among others, Nicholls (1972) suggests that an analysis of creative products is preferable to the trait-based approach in making predictions about creative potential, and Wallach (1976) proposes that student self-reports about creative accomplishment are sufficiently accurate to provide a usable source of data.

Although few persons would argue against the importance of including creativity in a definition of giftedness, the conclusions and recommendations discussed above raise the haunting issue of subjectivity in measurement. In view of what the research suggests about the questionable value of more objective measures of divergent thinking, perhaps the time has come for persons in all areas of endeavor to develop more careful procedures for evaluating the products of candidates for special programs.

Discussion and Generalizations

The studies reviewed in the preceding sections lend support to a small number of basic generalizations that can be used to develop an operational definition of giftedness. The first of these generalizations is that giftedness consists of an interaction among three clusters of traits—above average but not necessarily superior general abilities, task commitment, and creativity. Any definition or set of identification procedures that does not give equal attention to all three clusters is simply ignoring the results of the best available research dealing with this topic.

Related to this generalization is the need to make a distinction between traditional indicators of academic proficiency and creative productivity. A sad but true fact is that special programs have favored proficient lesson learners and test takers at the expense of persons who may score somewhat lower on tests, but who more than compensate for such scores by having high levels of task commitment and creativity. It is these persons whom research has shown to be those who ultimately make the most creative-productive contributions to their respective fields of endeavor.

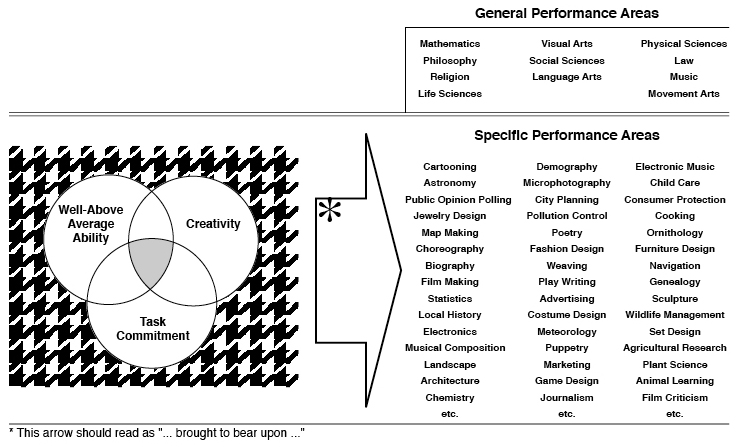

A second generalization is that an operational definition should be applicable to all socially useful performance areas. The one thing that the three clusters discussed above have in common is that each can be brought to bear on a multitude of specific performance areas. As was indicated earlier, the interaction or overlap among the clusters “makes giftedness,” but giftedness does not exist in a vacuum. Our definition must, therefore, reflect yet another interaction, but in this case it is the interaction between the overlap of the clusters and any performance area to which the overlap might be applied. This interaction is represented by the large arrow in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Graphic representation of the three-ring definition of giftedness.

A third and final generalization concerns the types of information that should be used to identify superior performance in specific areas. Although it is a relatively easy task to include specific performance areas in a definition, developing identification procedures that will enable us to recognize specific areas of superior performance is a more difficult problem. Test developers have thus far devoted most of their energy to the development of measures of general ability, and this emphasis is undoubtedly why these tests are relied on so heavily in identification. However, an operational definition should give direction to needed research and development, especially in the ways that these activities relate to instruments and procedures for student selection. A defensible definition can thus become a model that will generate vast amounts of appropriate research in the years ahead.

A Definition of Gifted Behavior

Although no single statement can effectively integrate the many ramifications of the research studies I have described, the following definition of gifted behavior attempts to summarize the major conclusions and generalizations resulting from this review of research:

Gifted behavior consists of behaviors that reflect an interaction among three basic clusters of human traits—these clusters being above average general and/or specific abilities, high levels of task commitment, and high levels of creativity. Gifted and talented children are those possessing or capable of developing this composite set of traits and applying them to any potentially valuable area of human performance. Children who manifest or are capable of developing an interaction among the three clusters require a wide variety of educational opportunities and services that are not ordinarily provided through regular instructional programs.

A graphic representation of this definition is presented in Figure 2, and the following “taxonomy” of behavioral manifestations of each cluster is a summary of the major concepts and conclusions emanating from the work of the theorists and researchers discussed in the preceding paragraphs:

General Ability:

– High levels of abstract thinking, verbal and numerical reasoning, spatial relations, memory, and word fluency.

– Adaptation to and the shaping of novel situations encountered in the external environment.

– The automatization of information processing; rapid, accurate, and selective retrieval of information.

Specific Ability:

– The application of various combinations of the above general abilities to one or more specialized areas of knowledge or areas of human performance (e.g., the arts, leadership, administration).

– The capacity for acquiring and making appropriate use of advanced amounts of formal knowledge, tacit knowledge, technique, logistics, and strategy in the pursuit of particular problems or the manifestation of specialized areas of performance.

– The capacity to sort out relevant and irrelevant information associated with a particular problem or area of study or performance.

– The capacity for high levels of interest, enthusiasm, fascination, and involvement in a particular problem, area of study, or form of human expression.

– The capacity for perseverance, endurance, determination, hard work, and dedicated practice. Self-confidence, a strong ego and a belief in one’s ability to carry out important work, freedom from inferiority feelings, drive to achieve.

– The ability to identify significant problems within specialized areas; the ability to tune in to major channels of communication and new developments within given fields.

– Setting high standards for one’s work; maintaining an openness to self and external criticism; developing an aesthetic sense of taste, quality, and excellence about one’s own work and the work of others.

– Fluency, flexibility, and originality of thought.

– Openness to experience; receptive to that which is new and different (even irrational) in the thoughts, actions, and products of oneself and others.

– Curious, speculative, adventurous, and “mentally playful;” willing to take risks in thought and action, even to the point of being uninhibited.

– Sensitive to detail, aesthetic characteristics of ideas and things; willing to act on and react to external stimulation and one’s own ideas and feelings.

As is always the case with lists of traits such as the above, there is an overlap among individual items, and an interaction between and among the general categories and the specific traits. It is also important to point out that all of the traits need not be present in any given individual or situation to produce a display of gifted behaviors. It is for this reason that the three-ring conception of giftedness emphasizes the interaction among the clusters rather than any single cluster. It is also for this reason that I believe gifted behaviors take place in certain people (not all people), at certain times (not all the time), and under certain circumstances (not all circumstances).

Section III: Discussion About the Three Rings

Since the original publication of the three-ring conception of giftedness (Renzulli, 1977), a number of questions have been raised about the overall model and the interrelationships between and among the three rings. In this section, I will use the most frequently asked questions as an outline for a discussion that will, I hope, clarify some of the concerns raised by persons who have expressed interest (both positive and negative) in this particular approach to the conception of giftedness.

Are There Additional Clusters of Abilities That Should Be Added to the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness?

One of the most frequent reactions to this work has been the suggestion that the three clusters of traits portrayed in the model do not adequately account for the development of gifted behaviors. An extensive examination of the research on human abilities has led me to an interesting conclusion about this question and has resulted in a modification of the original model. This modification is represented figurally by the houndstooth background in which the three rings are now imbedded (see Figure 1).

The major conclusion is that the interaction among the original three rings is still the most important feature leading to the display of gifted behaviors. There are, however, a host of other factors that must be taken into account in our efforts to explain what causes some persons to display gifted behaviors at certain times and under certain circumstances. I have grouped these factors into the two traditional dimensions of studies about human beings commonly referred to as personality and environment. The research4 clearly shows that each of the factors listed in Table 1 plays varying roles in the manifestation of gifted behaviors. What is even more important is the interaction between the two categories and among the numerous factors listed in each column (In fact, a houndstooth pattern was selected over an earlier checkerboard design in an effort to convey this interaction.) When we consider the almost limitless number of combinations between and among the factors listed in Table 1, it is easy to realize why so much confusion has existed about the definition of giftedness.

Table 1.

Personality and Environmental Factors Influencing Giftedness

aAlthough personal attractiveness is undoubtedly a physical characteristic, the ways in which others react to one’s physical being are quite obviously important determinants in the development of personality.

Each of the factors is obviously a complex entity in and of itself and could undoubtedly be subdivided into numerous component parts. The factor of socioeconomic status, for example, accounts for such things as prenatal care and nutrition, educational opportunities, and even things such as “occupational inheritance.” Werts (1968) found, for example, that there is a clear tendency for college students to gravitate toward the occupation of their fathers. On the personality side of the ledger, MacKinnon (1965) found that in studies of highly effective individuals it was discovered time and time again that persons of the most extraordinary effectiveness had life histories marked by severe frustrations, deprivations, and traumatic experiences. Findings such as these help to highlight the complexity of the problem. The advantages of high socioeconomic status, a favorable educational background, and early life experiences that do not include hardship, frustration, or disappointment may lead to a productive career for some individuals, but for others it may very well eliminate the kinds of frustration that might become the “trigger” to a more positive application of one’s abilities.5

An analysis of the role that personality and environment play in the development of gifted behaviors is beyond the scope of this chapter, and in many ways for school persons who are charged with the responsibilities of identifying and developing gifted behaviors, they are beyond the realm of our direct influence. Each of the factors above shares one or a combination of two characteristics. First, most of the personality factors are long-term developmental traits or traits that in some cases are genetically determined. Although the school can play an important role in developing things like courage and need for achievement, it is highly unrealistic to believe that we can shoulder the major responsibility for overall personality formation. Second, many factors such as socioeconomic status, parental personalities, and family position are chance factors that children must take as givens when they are born and that educators must take as givens when young people walk through the schoolhouse door. We can’t tell a child to be the firstborn or to have parents who stress achievement! It is for these reasons that I have concentrated my efforts on the three sets of clusters set forth in the original model. Of course, certain aspects of the original three clusters are also chance factors, but a large amount of research clearly has shown that creativity and task commitment are in fact modifiable and can be influenced in a highly positive fashion by purposeful kinds of educational experiences (Reis & Renzulli, 1982). And although the jury is still out on the issue of how much of one’s ability is influenced by heredity and how much by environment, I think it is safe to conclude that both general and specific abilities can be influenced to varying degrees by the best kinds of learning experiences.

Are the Three Rings Constant?

Most educators and psychologists would agree that the above average ability ring represents a generally stable or constant set of characteristics. In other words, if an individual shows high ability in a certain area such as mathematics, it is almost undeniable that mathematical ability was present in the months and years preceding a “judgment day” (i.e., a day when identification procedures took place) and that these abilities will also tend to remain high in the months and years following any given identification event. In view of the types of assessment procedures most readily available and economically administered, it is easy to see why this type of giftedness has been so popular in making decisions about entrance into special programs. Educators always feel more comfortable and confident with traits that can be reliably and objectively measured, and the “comfort” engendered by the use of such tests often causes them to ignore or only pay lip service to the other two clusters of traits.

In our identification model (Renzulli, Reis, & Smith, 1981), we have used above average ability as the major criterion for identifying a group of students who are referred to as the Talent Pool. This group generally consists of the top 15–20% of the general school population. Test scores, teacher ratings, and other forms of status information” (i.e., information that can be gathered and analyzed at a fixed point in time) are of practical value in making certain kinds of first-level decisions about accessibility to some of the general services that should be provided by a special program. This procedure guarantees admission to those students who earn the highest scores on cognitive ability tests. Primary among the services provided to Talent Pool students are procedures for making appropriate modifications in the regular curriculum in areas where advanced levels of ability can be clearly documented. It is nothing short of common sense to adjust the curriculum in those areas where high levels of proficiency are shown. Indeed, advanced coverage of traditional material and accelerated courses should be the “regular curriculum” for youngsters with high ability in one or more school subjects.

The task commitment and creativity clusters are a different story! These traits are not either present or absent in the same permanent fashion as pointed out in our mathematics example above. Equally important is the fact that we cannot assess them by the highly objective and quantifiable means that characterize test score assessment of traditional cognitive abilities. We simply cannot put a percentile on the value of a creative idea, nor can we assign a standard score to the amount of effort and energy that a student might be willing to devote to a highly demanding task. Creativity and task commitment “come and go” as a function of the various types of situations in which certain individuals become involved.

There are three things that we know for certain about the creativity and task commitment clusters. First, the clusters are variable rather than permanent. Although there may be a tendency for some individuals to “hatch” more creative ideas than others and to have greater reservoirs of energy that promote more frequent and intensive involvement in situations, a person is not either creative or not creative in the same way that one has high ability in mathematics or musical composition. Almost all studies of highly accomplished individuals clearly indicate that their work is characterized by peaks and valleys of both creativity and task commitment. One simply cannot (and probably should not) operate at maximum levels of output in these two areas on a constant basis. Even Thomas Edison, who is still acknowledged to be the world’s record holder of original patents, did not have a creative idea for a new invention every waking moment of his life. And the most productive persons have consistently reported “fallow” periods and even experiences of “burnout” following long and sustained encounters with the manifestation of their talents.

The second thing we know about task commitment and creativity is that they can be developed through appropriate stimulation and training. We also know that because of variations in interest and receptivity, some people are more influenced by certain situations than others. The important point, however, is that we cannot predetermine which individuals will respond most favorably to a particular type of stimulation experience. Through general interest assessment techniques and a wide variety of stimulus variation we can, however, increase the probability of generating a greater number of creative ideas and increased manifestations of task commitment in Talent Pool students. In our identification model, the ways in which students react to planned and unplanned stimulation experiences has been termed “action information.” This type of information constitutes the second level of identification and is used to make decisions about which students might revolve into more individualized and advanced kinds of learning activities. The important distinction between status and action information is that the latter type cannot be gathered before students have been selected for entrance into a special program. Giftedness, or at least the beginnings of situations in which gifted behaviors might be displayed and developed, is in the responses of individuals rather than in the stimulus events. This second-level identification procedure is, therefore, part and parcel of the general enrichment experiences that are provided for Talent Pool students, and is based on the concept of situational testing that has been described in the theoretical literature on test and measurements (Freeman, 1962, pp. 538–54).

Finally, the third thing we know about creativity and task commitment is that these two clusters almost always stimulate each other. A person gets a creative idea; the idea is encouraged and reinforced by oneself and/or others. The person decides to “do something” with the idea and thus his or her commitment to the task begins to emerge. Similarly, a large commitment to solving a particular problem will frequently trigger the process of creative problem solving. In this latter case we have a situation that has undoubtedly given rise to the old adage “necessity is the mother of invention.”

This final point is especially important for effective programming. Students participating in a gifted program should be patently aware of opportunities to follow through on creative ideas and commitments that have been stimulated in areas of particular interest. Similarly, persons responsible for special programming should be knowledgeable about strategies for reinforcing, nurturing, and providing appropriate resources to students at those times when creativity and/or task commitment are displayed.

Are the Rings of Equal Size?

In the original publication of the three-ring conception of giftedness, I stated that the clusters must be viewed as “equal partners” in contributing to the display of gifted behaviors. I would like to modify this position slightly, but will first set forth an obvious conclusion about lesson-learning giftedness. I have no doubt that the higher one’s level of traditionally measured cognitive ability, the better equipped he or she will be to perform in most traditional (lesson) learning situations. As was indicated earlier, the abilities that enable persons to perform well on intelligence and achievement tests are the same kinds of thinking processes called for in most traditional learning situations, and therefore the above average ability cluster is a predominant influence in lesson-learning giftedness.

When it comes to creative-productive giftedness, however, I believe that an interaction among all three clusters is necessary for high-level performance. This is not to say that all clusters must be of equal size or that the size of the clusters remains constant throughout the pursuit of creative-productive endeavors. For example, task commitment may be minimal or even absent at the inception of a very large and robust creative idea; and the energy and enthusiasm for pursuing the idea may never be as large as the idea itself. Similarly, there are undoubtedly cases in which an extremely creative idea and a large amount of task commitment will overcome somewhat lesser amounts of traditionally measured ability. Such a combination may even cause a person to increase her or his ability by gaining the technical proficiency needed to see an idea through to fruition. Because we cannot assign numerical values to the creativity and task commitment clusters, empirical verification of this interpretation of the three rings is impossible. But case studies based on the experience of creative-productive individuals and research that has been carried out on programs using this model (Reis, 1981) clearly indicate that larger clusters do in fact compensate for somewhat decreased size on one or both of the other two areas. The important point, however, is that all three rings must be present and interacting to some degree in order for high levels of productivity to emerge.

Summary: What Makes Giftedness?

In recent years we have seen a resurgence of interest in all aspects of the study of giftedness and related efforts to provide special educational services for this often neglected segment of our school population. A healthy aspect of this renewed interest has been the emergence of new and innovative theories to explain the concept and a greater variety of research studies that show promise of giving us better insights and more defensible approaches to both identification and programming. Conflicting theoretical explanations abound and various interpretations of research findings add an element of excitement and challenge that can only result in greater understanding of the concept in the years ahead. So long as the concept itself is viewed from the vantage points of different subcultures within the general population and differing societal values, we can be assured that there will always be a wholesome variety of answers to the age-old question: What makes giftedness? These differences in interpretation are indeed a salient and positive characteristic of any field that attempts to further our understanding of the human condition.

In this chapter, I have attempted to provide a framework that draws upon the best available research about gifted and talented individuals. I have also reviewed research offered in support of the validity of the three-ring conception of giftedness. The conception and definition presented in this chapter have been developed from a decidedly educational perspective because I believe that efforts to define this concept must be relevant to the persons who will be most influenced by this type of work. I also believe that conceptual explanations and definitions must point the way toward practices that are economical, realistic, and defensible in terms of an organized body of underlying research and follow-up validation studies. These kinds of information can be brought forward to decision makers who raise questions about why particular identification and programming models are being suggested by persons who are interested in serving gifted youth.

The task of providing better services to our most promising young people can’t wait until theorists and researchers produce an unassailable ultimate truth, because such truths probably do not exist. But the needs and opportunities to improve educational services for these young people exist in countless classrooms every day of the week. The best conclusions I can reach at the present time are presented above, although I also believe that we must continue the search for greater understanding of this concept which is so crucial to the further advancement of civilization. Perhaps the following quotation by Arnold Gesell best summarizes the state of the art: “Our present day knowledge of the child’s mind is comparable to a fifteenth century map of the world—a mixture of truth and error. Vast areas remain to be explored. There are scattered islands of solid dependable facts, uncoordinated with unknown continents.”

References

1Persons interested in a succinct examination of problems associated with defining intelligence are advised to review The Concept of Intelligence (U. Neisser, 1979).

2The term gifted education will be used in substitution for the more technically accurate but somewhat awkward term education of the gifted.

3For example, most of the research on the “gifted” that has been carried out to date has used high-IQ populations. If one disagrees (even slightly) with the notion that giftedness and high IQ are synonymous, then these research studies must be reexamined. These studies may tell us a great deal about the characteristics, and so on, of high-IQ individuals, but are they necessarily studies of the gifted?

4Literally hundreds of research studies have been carried out on the factors listed. For persons interested in an economical summary of personality and environmental influences on the development of gifted behaviors, I would recommend the following: History and the Eminent Person (D. K. Simonton, 1978); Science as a Career Choice: Theoretical and Empirical Studies (B. T. Eiduson and L. Beckman, 1973).

5I am reminded of the well-known quote by Dylan Thomas: “There’s only one thing that’s worse than having an unhappy childhood, and that’s having a too-happy childhood.”