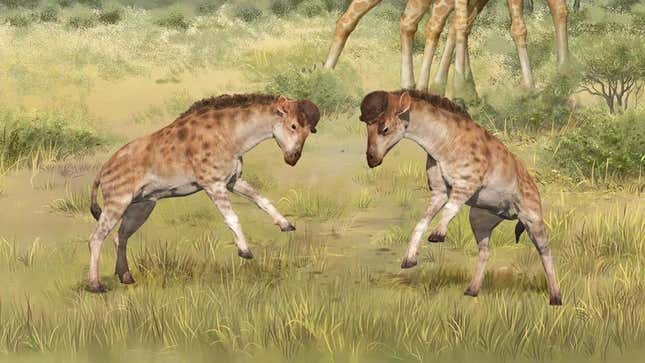

A key use of giraffes’ long necks is necking, a form of combat in which two giraffes swing their necks at one another, slamming opponents with their heads, to establish dominance. Now, researchers have described a previously unknown giraffe ancestor with a similar anatomy for fighting, in the form of a reinforced, helmet-like skull.

The animal is called Discokeryx xiezhi, and it lived in the Miocene epoch, around 16.9 million years ago. Fossils of the giraffe relative (or giraffoid) were discovered in northern China and were immediately noticed for the unique structure of the neck and head bones, which indicated that the animal was built for delivering and withstanding blunt force. The team’s analysis of D. xiezhi’s anatomy and what it tells us about giraffoid evolution is published today in the journal Science.

In the paper, the research team describes D. xiezhi’s headgear and neck joints, as well as an analysis of isotope data from fossilized tooth enamel. They posit that the giraffoid grazed on open land—presumably on foliage much closer to the ground than the trees that modern giraffes snack on.

Though the necks of giraffes are the animals’ most obvious trait, giraffoid headgear is weird across the board. For one, the animals’ ossicones (skin-covered hornlike structures) evolved into antlers in some extinct giraffoids, while other species developed thick, visor-like brows on their skulls. In D. xiezhi, the headwear of choice is a helmet.

In the new paper, the team reports that D. xiezhi had thickened vertebrae and skullcap, which would’ve made the animals terrific headbutters. The team compared the headbutting ability of three extant headbutters—musk ox, Argali sheep, and blue sheep—and found that D. xiezhi’s cranium absorbed more strain energy and better protected parts of the brain than the crania of modern species. “To the best of our knowledge,” the team wrote in the paper, “D. xiezhi exhibits the most optimized head-butting adaptation in vertebrate evolution.”

Modern giraffes are social animals, with cohesive social structures that may be matriarchal, akin to intelligent species like orcas and elephants. But that doesn’t stop the 19-foot-tall mammals from having their fair share of disputes, to establish dominance and to compete for mates. According to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, both giraffe bulls and cows have been observed necking, and similar aggressive displays are seen in giraffe relatives like the enigmatic okapi.

“The fact that okapi, giraffe’s closest relative, use its head as both a club and for head-butting, says to me that head-butting and neck-fighting behaviors are not fundamentally different; which one is used is related to neck length,” said Douglas Cavener, a biologist and geneticist at Penn State University, who was not affiliated with the new paper. “The discovery of Discokeryx, with highly developed headgear, adds an excellent example of giraffoids predilection for developing elaborate headgear, unique to graffoids, for male-male competition.”

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin used the giraffe’s neck as an example of natural selection; the animal adapted to its environment, evolving a longer neck to reach foliage other species could not. But D. xiezhi’s helmet head adds credence to the so-called “necks for sex” hypothesis, which holds that modern giraffe’s elongated necks evolved for sexual purposes, rather than to reach lofty foliage.

“While I think this paper supports the necks-for-sex hypothesis for evolution of giraffe’s long neck, I don’t think that it is the final word,” Cavener said. “It is still possible that giraffe’s necks evolved to reach higher browse and thus occupy a unique feeding niche.”

In a way, it’s a chicken-or-the-egg question. Whichever carnal need primarily fueled the giraffe’s elongated neck, its clear that the other need benefited from the development.

More: This Huge, Four-Horned Mammal Is Rewriting Giraffe Prehistory