Prior to the sixteenth century’s Protestant Reformation there were few formal burying grounds for those who were not nobles. The remains of royalty, nobility, and high-ranking clergy members were often entombed in the walls of churches and cathedrals, with the areas closest to the altar being reserved for the most important members of society.

The social changes spurred on by the Reformation – and the necessity of finding new spaces with the walls of churches nearing their capacity – led to the dead being interred in burial grounds, often known as God’s Acres. The emergence of these cemeteries opened up the possibility of a tombstone for members of the middle class, which meant an opportunity to be remembered.

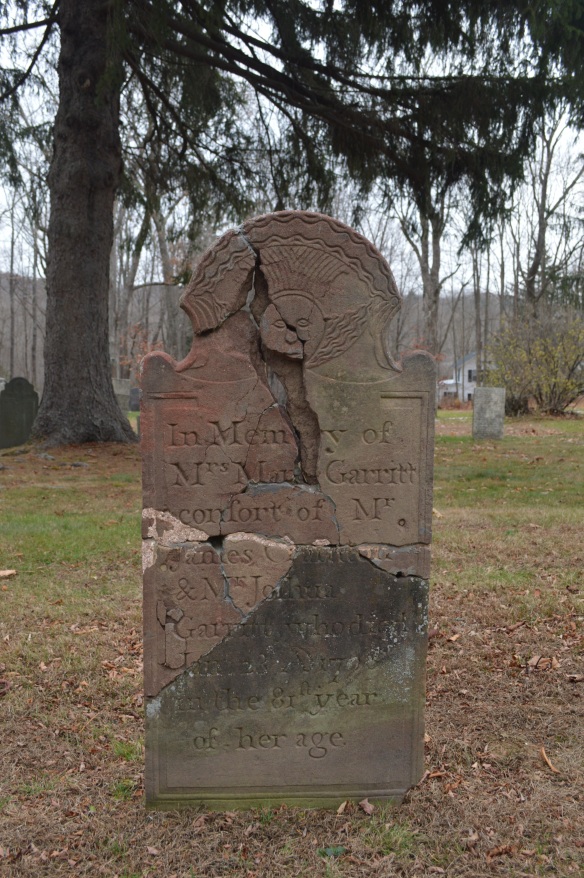

Much of New England’s tombstone art followed the lead of the Puritans, who were particularly macabre in their engravings. Puritan theology held that only the “Elect” would make it to heaven; the rest of mankind just died, were buried, and rotted in the ground. These beliefs are reflected in Puritan gravestone art, with the classic words, “Here lies of the body of …” engraved below a skull or skull and crossbones.

However, a loosening of the grip of conservative Puritanism led to more optimistic gravestones, with skulls being swapped for human faces, and crossbones giving way to angels’ wings. Equally telling is a subtle change in the wording, with “Here lies the body of …” often giving way to “Here lies the mortal remains,” language that allowed for the possibility of a human soul.

For more information on cemetery art, see Douglas Keister’s excellent Stories in Stone.

Pingback: East Cemetery: Floral Symbolism | Hidden in Plain Sight