Marlborough College Chapel

Art and Vision

Contents Introduction 08 A Pre-Raphaelite Comes to Town 10 John Roddam Spencer Stanhope –‘A Painter of Dreams’ 14 The Ministration of Angels on Earth 20 Stanhope’s Variants 26 The Twelve Paintings 28 A Note on Stanhope’s Materials 52 Stanhope’s Secret Language of Flowers 54 The Decorative Woodcarving 58 Looking back at Stanhope 6 4 Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and the Scholars’ Window 6 6 The Chancel Windows 70

Rising high above the Old Bath Road on one side and the eclectic buildings of Court on the other, the noble exterior of Marlborough College Chapel proclaims to the communities of town and College the school’s core Christian values and Anglican heritage.

The felicitous ensemble of steep roof, sturdy buttresses, winding tracery, and soaring flèche serves as an outward sign of the solemn place within, and it is with this remarkable interior that the current volume, one of two to be published on the Chapel this year, is concerned.

The year 2023 marks a significant anniversary in the genesis of the Chapel’s interior because it is one hundred and fifty years since the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Roddam Spencer Stanhope began work on his decorative panels for Marlborough College’s Chapel of St Michael and All Angels. This project paved the way for his commission to carry out work on the Chapel’s chief glory, the twelve paintings of ‘The Ministration of Angels on Earth’, a pictorial cycle tracing the Christian story from the Fall of Adam to the New Jerusalem. At the same time, the College enlisted two of the most prominent artists

The Master’s Preface

of the age, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris (Aa 1848-51), to design a window honouring its scholars, a commission, which in tandem with Stanhope’s masterpieces, transformed the Chapel into something of a showcase of Victorian fine and applied art.

And yet, for all the undoubted beauty of the work carried out by these distinguished figures, the visual and emotional success of the interior is not down to the power of any one individual work, but to the collective whole. It is therefore the intention of this volume to acknowledge the role of other artists, their names long lost to view, who helped fashion the Chapel as we see it today. These figures, whether stone-carvers, glassmakers, textile artists, carpenters, gilders, tinters, or ironworkers, command our admiration still. It is a particular distinction of this volume that we hear

from pupils past and present of their appreciation for the remarkable spiritual environment they have enjoyed in their time at Marlborough.

We in the College community are fortunate to experience the Chapel and its glorious works of art regularly at close hand. It is our hope that this publication, and its companion volume on the Chapel’s history and architecture, will enable others at further remove to appreciate the consummate skill that artists long ago devoted to a building set aside in perpetuity for the spiritual nurture and enrichment of Marlborough College’s pupils.

Louise Moelwyn-Hughes

Master

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 05

Art and Vision

Victorian Masterpieces in Marlborough College Chapel

Since 1886, it has played a central part in the spiritual and moral education of tens of thousands of Marlburians, silently ministering to their profounder sensibilities through the persuasive language of artistic beauty and consummate craftsmanship. Its décor is astonishingly varied, a felicitous array of soaring architecture, sparkling stained glass, richly painted canvases, parcel-gilt wood panelling, learned inscriptions, and more, fashioned from a host of materials, whether stone, alabaster, glass, wood, ironwork, textiles, ceramics, and even, if one looks hard enough, Bakelite. Indeed, the interior provides a perfect example of what German art historians might term a Gesamtkunstwerk, a ‘total work of art’, the sum of many parts uniting to form a greater, deeply satisfying whole.

It is right to turn our focus upon the interior of Marlborough’s Chapel, having in a companion volume surveyed with Dr Niall Hamilton the history of the College’s two chapels, and the architectural achievements of their

builders: Edward Blore for the first Chapel, which stood from 1848 to 1884, and George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner for the second, the fine building consecrated in 1886 and still in use today. It has been the belief of every Master of the College from Matthew Wilkinson’s time down to the present that the Chapel should offer a place of inspiration for the community that by its very elegance and dignity might elevate thoughts from the mundane and immediate to those of a higher and more enduring order.

It is also fitting to look with particular focus at the greatest treasure of the Chapel’s interior, the remarkable series of paintings carried out for Marlborough by the important Pre-Raphaelite artist, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. This year, 2023, marks the sesquicentennial of Stanhope’s first commission for the College, the panels of angels that stand high above the Chapel gallery, work that emboldened the Master of the day, the Revd Frederic Farrar, to engage the painter’s services for a grander, more

developed scheme. This was to be his series of twelve canvases, The Ministration of Angels on Earth, not only the largest commission of that distinguished painter’s career, or the most extensive cycle of Pre-Raphaelite paintings in any school, but a substantial pictorial series of real importance to the history of nineteenthcentury British art. In the pages that follow, we tell with new insights the story of the commission, its execution, and the pictures’ reception as they became part of the College’s cultural fabric. We shall also discuss the pictures’ themes, their sources, and their treatment, and explore some of the often-abstruse symbolism with which Stanhope invested their narratives.

In addition to discussing the Stanhope paintings, this volume considers some of the more notable examples of applied art in the Chapel, beginning with the Scholars’ Window, a beautiful and early example of Arts and Crafts stained glass designed by Edward Burne-Jones under the direction of William Morris. We also focus on the exquisite but easily missed

08 Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Marlborough College’s Chapel presents one of the most spectacular and sumptuous school interiors to be found anywhere in the world.

Introduction

windows gracing the side chapels of the chancel, the work of Burlison and Grylls, pre-eminent painters of Victorian church glass. The Chapel’s ornate woodcarving amply repays closer scrutiny, and we ponder over the intricate panels that encase the lower walls of the nave, paying due attention to the ciphers and symbols with which it was enriched by the Bristol craftsman William Wilmut and his assistants. In some of these appraisals, I have called upon College History of Art pupils, past and present, to offer personal reflections upon work they know so well. Their ready response testifies to the affection felt for a building that has inspired generations of Marlburians through sustained exposure to artistry of real eloquence and power; proof, if it was needed, that our Chapel continues to uplift those receptive to its atmosphere of contemplation and quiet repose.

Dr Simon McKeown Head of History of Art

Dr Simon McKeown Head of History of Art

09

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

A Pre-Raphaelite Comes to Town

On the morning of 23rd September 1873, the PreRaphaelite artist John Roddam Spencer Stanhope hopped on a 7 o’clock train at Paddington accompanied by one of his studio assistants. His destination was Marlborough, where he alighted just over three hours later. The object of his journey was the town’s burgeoning College which had recently offered him a commission to carry out decorative work on the interior of its first Chapel.

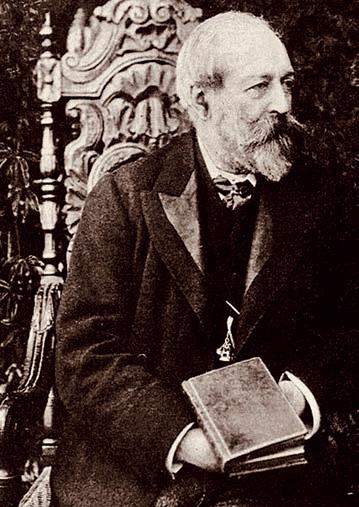

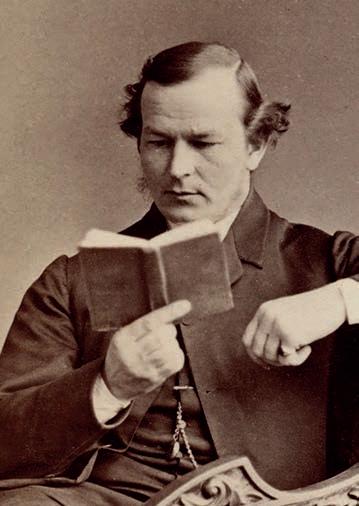

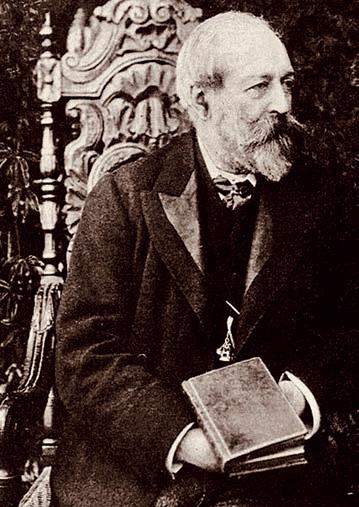

This building, designed in an austere Gothic idiom by Edward Blore and consecrated in 1848, had been severely criticised by the Tractarian architectural bulletin, The Ecclesiologist, which notoriously disliked any style other than the Decorated, or Middle Pointed. However, its appeal for an enrichment of the interior was heeded by the College’s new Master of the early 1870s, the Revd Frederic Farrar. A man of deep piety and illimitable energy, Farrar was convinced that ‘the chapel in which 570 boys meet morning and evening […] ought to be as beautiful as our opportunities enable us to make it.’ To that end, he engaged the services of the architects George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner to arrange a programme of decoration for the roof and walls of the Chapel’s plain interior, work which largely devolved to the ecclesiastical craftsman F. R. Leach, and which was to include carved and painted panels to frame the East Window. The subject of this furnishing was to be an ensemble of angels playing musical instruments, a visual theme in keeping with the Chapel’s dedication to St Michael and All Angels.

It was Bodley who recommended Stanhope’s name to Farrar as an artist suited for the task; the architect knew the painter well since they had for some years belonged to the same circle of friends and were near neighbours on London’s Harley Street. Moreover, Bodley had asked Stanhope in 1869 to paint panels of angels for the facia of the organ-case of St Martin’s Church in Scarborough, and his work there had been deemed a success. We must therefore imagine that Stanhope felt confident of his powers when he arrived at the College that September morning 150 years ago to take measurements for the task ahead. What he could not have known was that he was embarking upon a relationship with Marlborough College that was to last for the next fifteen years.

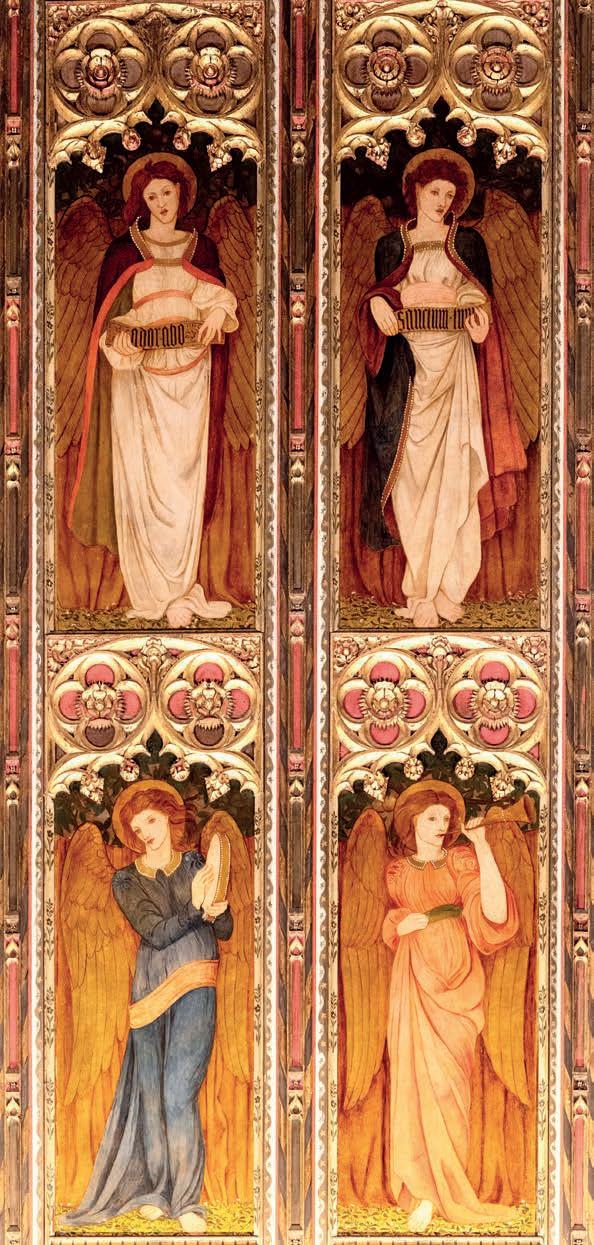

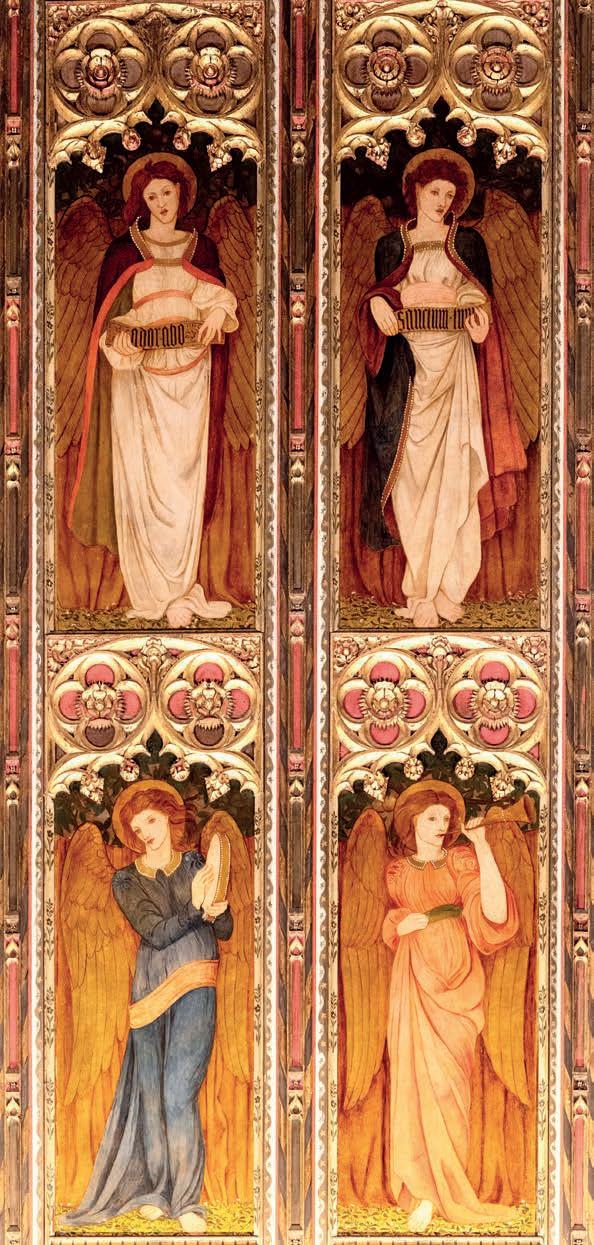

Stanhope performed his commission to the letter, completing the panels in 1874. Arranged in groups of six to each side of the Altar, four angels sing God’s glory from Latin-inscribed banderoles to the accompaniment of their fellows on lute, timbrel, trumpet, bagpipe, cymbals,

shawm, and psaltery. Executed with more emphasis upon line than volume, the angels, with impassive expressions and robes of bright hues, seem to sway to the divine harmony, creating a pleasing decorative effect from the tips of their golden wings to the flowery meadows beneath their feet. The success of the commission emboldened Farrar to entrust Stanhope with a larger and more ambitious pictorial project for the Chapel: a series of twelve large canvases illustrating the lofty theme of ‘The Ministration of Angels on Earth.’ It was to this great commission that Stanhope now turned.

Marlborough

College Chapel: Art and Vision

10

11

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

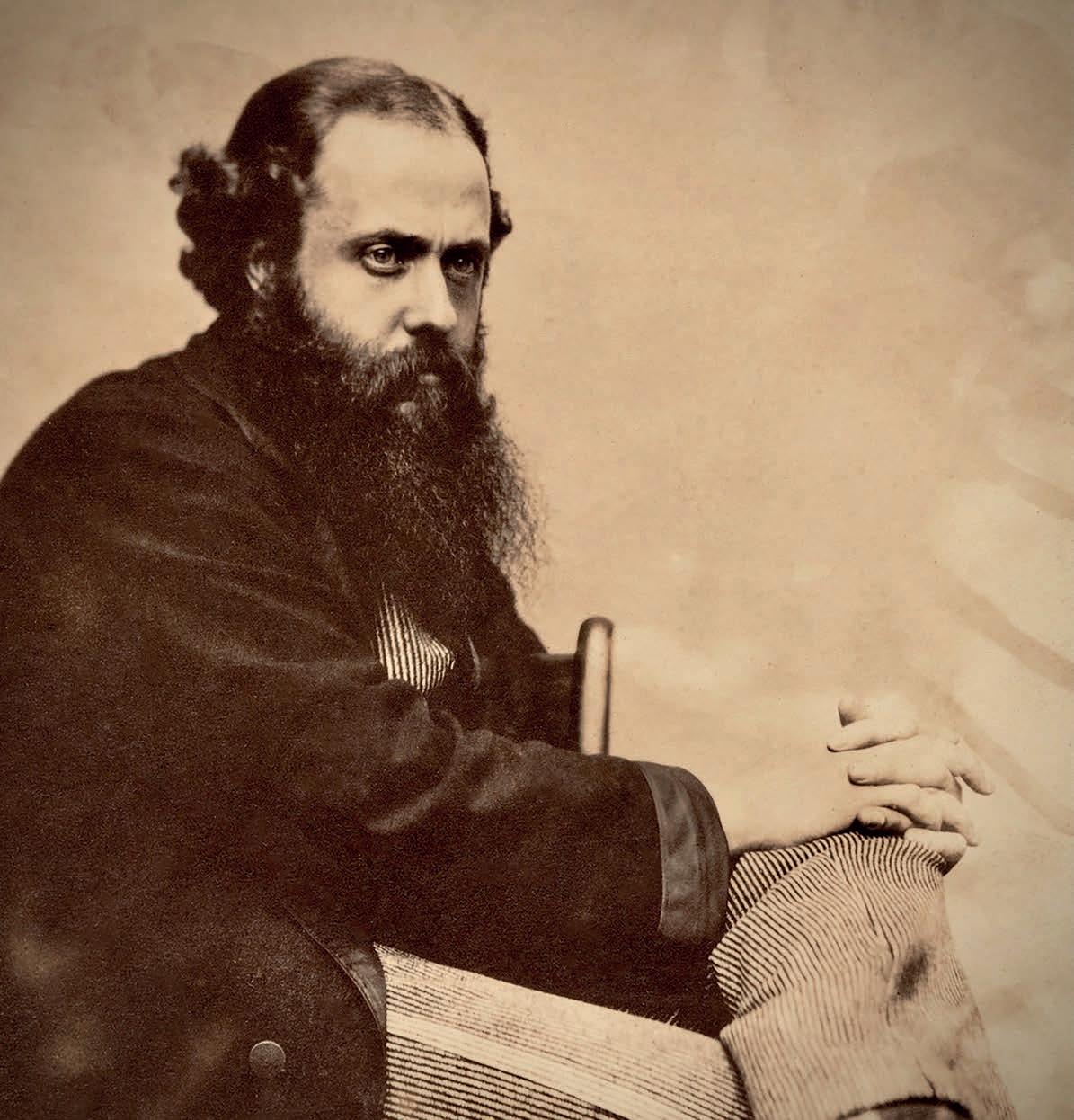

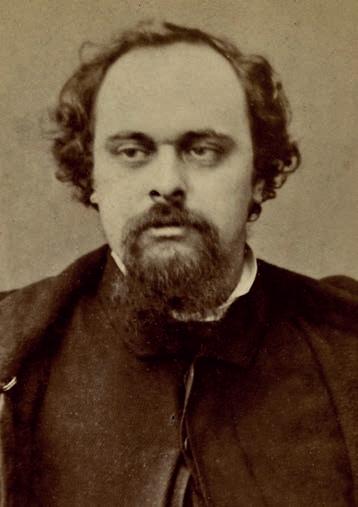

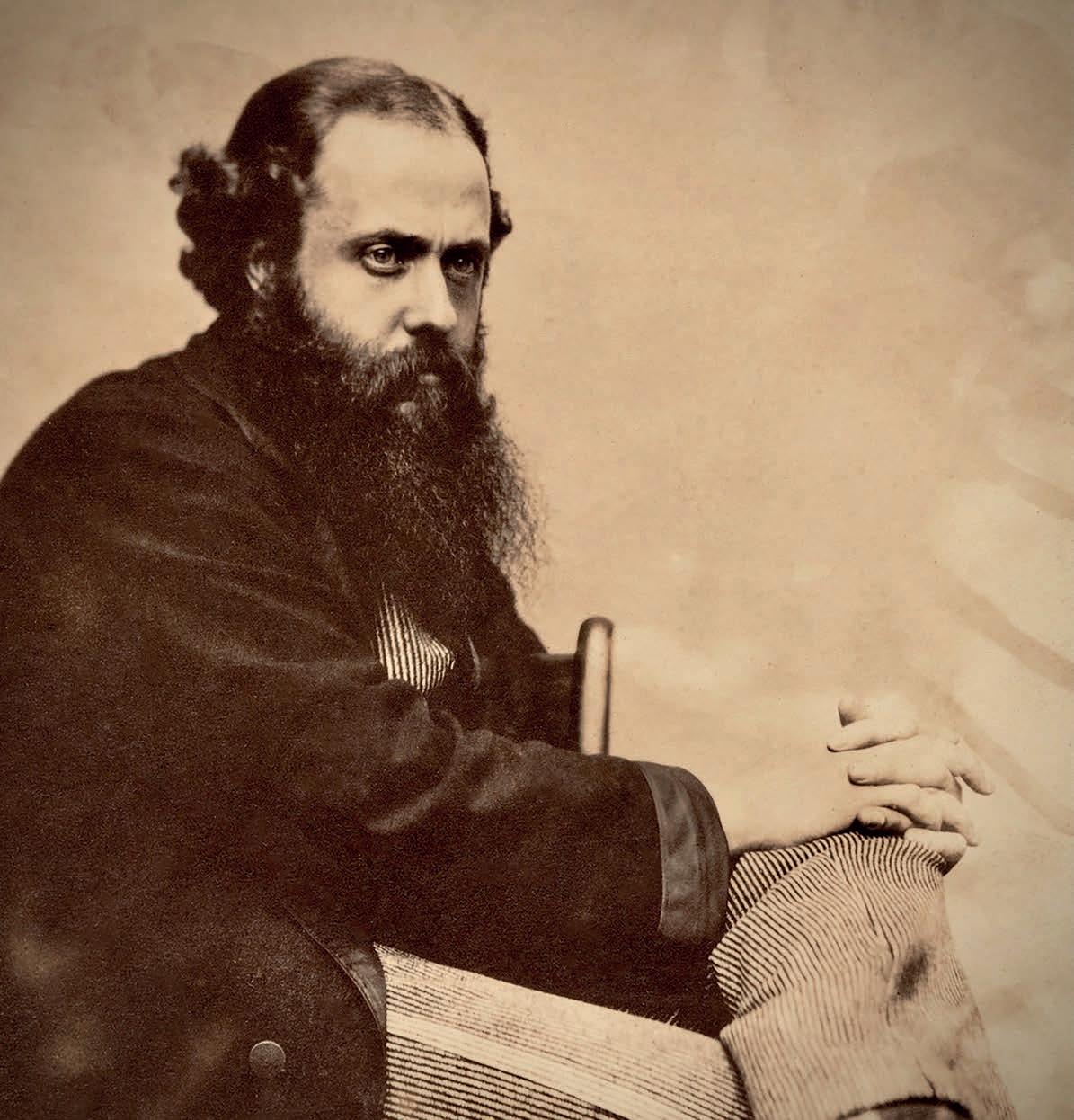

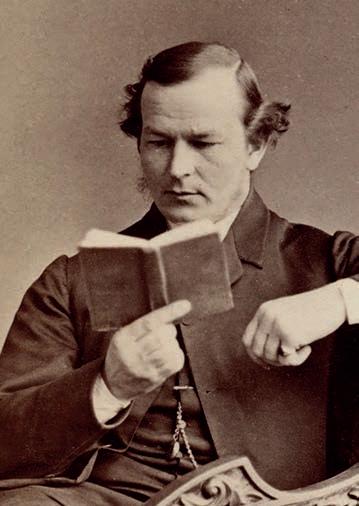

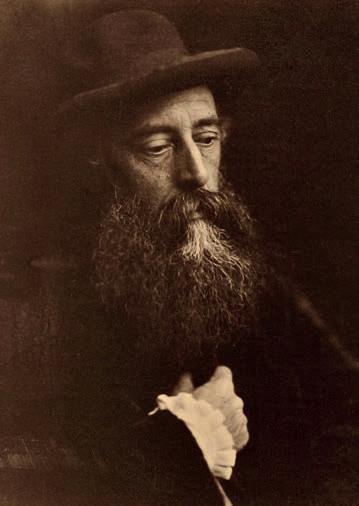

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, 1857

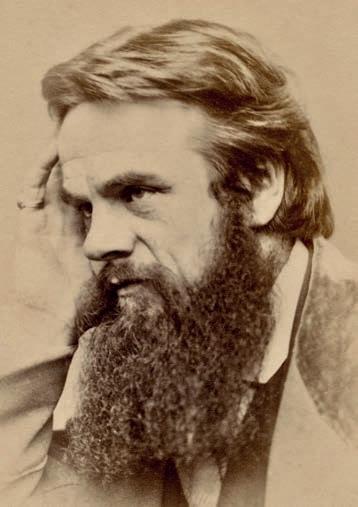

George Frederick Bodley, 1899

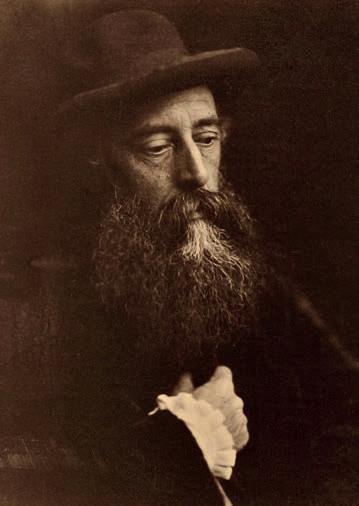

Revd Frederic Farrar, 1870s

12

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Ensemble of Angels

North side of West Window

13

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Ensemble of Angels

South side of West Window

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope –‘A Painter of Dreams’

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829-1908), called Roddam, or Roddy to his friends, belonged to the so-called ‘second generation’ or ‘second wave’ of Pre-Raphaelite artists that emerged in the latter half of the 1850s.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 14

Ethel Bower, Portrait medal of Stanhope, 1906

He was born in Yorkshire to John Spencer Stanhope, a landowner and classicist, and Elizabeth Wilhelmina Coke, the daughter of the Earl of Leicester. His mother spent much time as a child at the family seat at Holkham Hall in Norfolk, where she had met Constable, Turner, and Flaxman, all client artists of her father –although the tradition that she had been taught drawing by Gainsborough may be discounted as family myth. When Roddam married in 1859, he took as his bride a woman from the same social tier, Elizabeth King, the great-great-niece of Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset, whose principal seat at Marlborough was the mansion we now know as C1.

Educated at Rugby and Christ Church, Oxford, Roddam briefly dallied with a career in the Army, but soon resigned his commission in favour of life as an artist. In this, he proved to be no dilettante, prompting his mother to write, ‘I never saw anything so crazy as Roddy is on pictures. If he perseveres, he must surely make something of it, as it is his sole thought and object, thank God a harmless one.’

But for all her sympathies, Elizabeth could not easily accept that a young man born to high estate should seek to follow a career that still carried the taint of a lowly craft. Undeterred by his family’s disapproval, Roddam persuaded the painter George Frederic Watts to take him on as a pupil. Watts, a rising star in British art, proved inspirational to Stanhope, although the effectiveness of his gentle, uncritical tuition proved negligible. The two men became close friends, and Stanhope travelled to Italy in 1853 with Watts as his cicerone.

It was through Watts that Stanhope was introduced to members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, that youthful, rebellious movement in British art that championed a bright, colourful, and meticulous style in emulation of Italian masters before Raphael, and in defiance of what its members deemed the staid, academic teaching of the Royal Academy Schools. Formed in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, the Brotherhood had faltered after only

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

15

William Holman Hunt, 1865

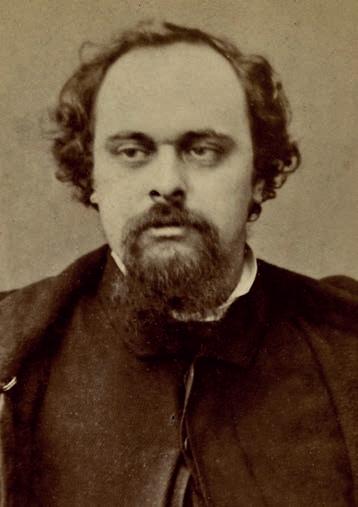

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1862

John Everett Millais, 1857

Julia Margaret Cameron, Portrait of George Frederic Watts, 1864

a few years; but its ideals were cherished and continued among a group of young Oxford-educated disciples that included William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Watts, a permanent house guest of the wealthy civil servant Thoby Prinsep and his wife Sara, invited Stanhope to Sunday salons held at the Prinseps’ Kensington home, Little Holland House. There he met Charles Dickens, William Gladstone, William Makepeace Thackeray, and his future collaborator at Marlborough, George Frederick Bodley. One memorable afternoon he was introduced to Rossetti, Hunt, and other members of the PreRaphaelite circle, who encouraged Stanhope’s early efforts in painting. It was on the strength of their appreciation of his ‘Thoughts of the Past,’ now Stanhope’s best-known painting at the Tate, that he was asked in 1857 to join Rossetti, Morris, Burne-Jones, and others in painting murals for the library of the Oxford Union building. Eager to follow in the footsteps of Quattrocento frescoists, but armed with more enthusiasm than expertise, the high-spirited company botched the job, applying paint to badly prepared ground,

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 16

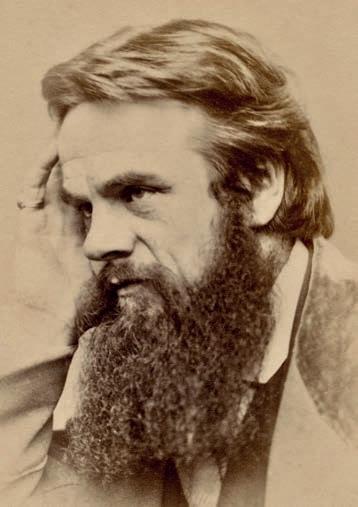

Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris,

1874

so that the pigment flaked off within months of the scaffolding coming down. More enduring was the firm friendship enkindled between Stanhope and ‘Ned’ Burne-Jones as they worked long weeks side by side on the doomed project. They were temperamentally similar, goodhumoured, quiet men who liked books and amiable company, but shared a strong work ethic. Over many years they enjoyed painting in each other’s company, with Burne-Jones using Stanhope’s London studio as one of his bases. Appreciating the importance of observations from life, Burne-Jones and Stanhope often drew from the same pool of models for their faces, hands, and figures. The likeness of one of them, Marie Spartali, herself an able painter, recurs throughout the Marlborough series.

Observing the closeness of the two men, some art historians have bracketed Stanhope as a weak imitator of BurneJones’s style and subject matter, but this was not a characterisation Burne-Jones would have recognised as just. Instead, he was full of praise for his less-lauded

friend, recalling his ‘extraordinary turn for landscape […] quite individual’, and especially his boldness of palette:

‘Stanhope is the greatest colourist of the century […] his colour is beyond anything the finest in Europe.’ But while the work of the two painters bears superficial resemblances, these have much to do with the visual language of the school which they both admired. Both men drew their inspiration from painters of the Italian Middle Ages and Renaissance: from Giotto, Masaccio, Mantegna, and more particularly, Fra Angelico, Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Giovanni Bellini, and Leonardo. In truth, the two men’s creative responses to these great exemplars varied sharply. Stanhope’s early biographer, A. M. W. Stirling, was perceptive indeed when she remarked that ‘a similar idea appealed to both BurneJones and Stanhope, but the work of the former is essentially Greek in character, that of the latter is Florentine.’ It might be added that while the solemnity of Stanhope’s imagery derives from the Tuscan style, his palette owes much to the polychromy of Renaissance Venice.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 17

Julia

Margaret Cameron, Portrait of Marie Spartali, 1868

Moreover, the sensuous, otherworldly atmosphere of his work has led some art historians to link Stanhope with the Aesthetic Movement that emerged in the 1860s, and Stanhope indeed regularly exhibited at that movement’s spiritual home, the Grosvenor Gallery which opened on Bond Street in 1877. There, Stanhope’s pictures kept company with the work of Albert Moore, Lord Leighton, James Tissot, and James McNeill Whistler.

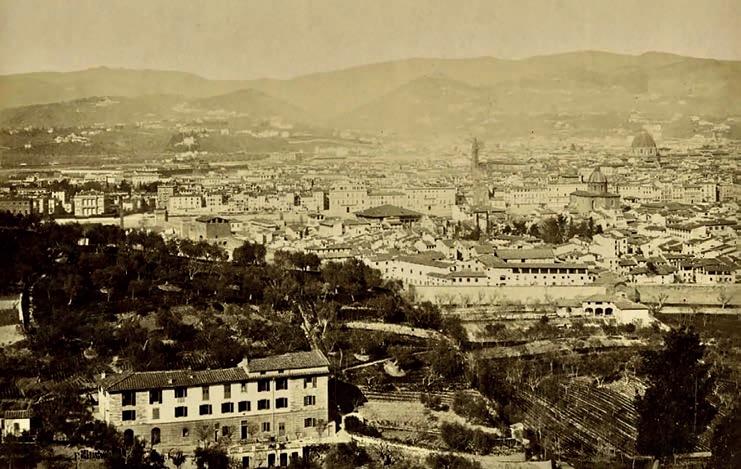

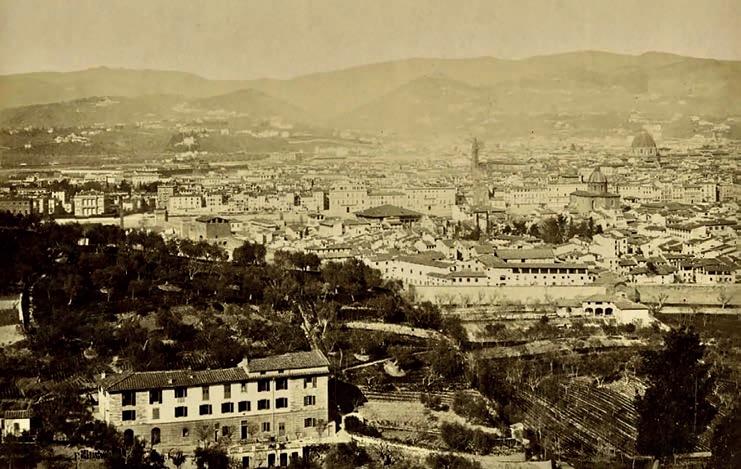

Stanhope suffered throughout his life from chronic asthma, causing him to move house frequently in a restless search for environments that might alleviate his condition. His private income granted him the means to seek relief in warmer climes, and from the mid-1860s on he became a regular visitor to Italy, joining the traffic of English émigrés convinced of the healthful air of the Fiesole Hills. In 1873, he bought the Villa Nuti (now Villa ’lo Strozzino), a fifteenth-century mansion on the crest of Bellosguardo, a hill east of Florence celebrated for its views over the city, moving there permanently in 1880.

18

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Although he never integrated into Tuscan society, and indeed stood rather aloof from it, he found ready companionship among English exiles. His studio, for example, stood adjacent to that of his model Marie Spartali, now resident at Bellosguardo with her American husband, William James Stillman, the journalist and photographer. Stanhope was naturally

sociable, and Villa Nuti became a hub for English artists visiting Florence, among them Morris, Burne-Jones, Hunt, Walter Crane – and George Frederick Bodley. Burne-Jones believed the move had brought health benefits to his friend but feared he risked isolation from artistic currents in London. Regardless, Stanhope continued to paint with great dedication,

studying the storehouses of Tuscan Masters in the churches and palaces of the city below, and invoking their atmosphere in panels sent to London for exhibition. From the later 1870s on, he experimented with tempera, that quintessential medium of the Florentine Renaissance, and became so adept in its techniques that he helped found The Society of Painters in Tempera in 1901.

Asthma was not to play a part in Stanhope’s death, which came in his eightieth year in August 1908, ten years after that of his great friend, Burne-Jones. Stanhope was buried in Florence’s Protestant Cemetery, his place of rest marked by a stone he had himself designed. A memorial exhibition was held at the Carfax Gallery in London in the spring of 1909, organised by Stanhope’s niece, the painter Evelyn De Morgan and her ceramicist husband, William. In a review published in The Morning Post on 11th March entitled ‘The Painter of Dreams’, the author observed a link between the man and his manner:

His pictures somewhat resemble his own life in its aloofness. They are abstract visions created in the far depths of a cloistered mind. His gracious figures seem to be voiceless actors in our most pure and pensive dreams […] Angels move voicelessly among trees that murmur not, for the winds are at rest, the bird’s songs mute, and the waters pass softly as falling snow.

We must assume that some of these qualities of otherworldliness and refined sensibility appealed to the poetic and sensitive Farrar, and that he hoped the artist’s angelic visions at Marlborough would serve as visual counterpoints to his own finely turned sermons delivered in their midst.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

19

View of Florence from Bellosguardo, 1880

The Ministration of Angels on Earth

The series of twelve paintings by John Roddam

Spencer Stanhope in Marlborough College Chapel has long been known collectively as ‘The Ministration of Angels on Earth’, a title first recorded in 1889.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 21

The theme demonstrates how God has revealed his will to humankind through the agency of angels, a subject conveyed through twelve narrative episodes from the Bible featuring angelic visitations. Six canvases on the north wall present accounts from the Old Testament (five from the Book of Genesis, one from the Book of Daniel), and six on the south wall illustrate passages from the New Testament (five from the Gospels, one from the Revelation of St John). Both sets of six pictures are intended to be read sequentially in an eastward direction from the Chapel’s west door to the end of the nave.

The theme of angels, chosen because of the Chapel’s dedication to St Michael and All Angels, was a perfect subject for a Pre-Raphaelite artist, since angels had been frequently depicted in the repertoire of the movement from the very beginning, particularly in the work of Rossetti. Although Frederic Farrar appointed Stanhope to perform the task, it is unclear who drew up the details of the programme, namely selecting the biblical episodes, titles for each scene, or the Latin texts incorporated into the carved frames. Some attempt has been made to assign the authorship of the programme to Farrar, seeing significance in a sermon he delivered at Marlborough while assistant master at Harrow. Preached on Founders’ Day, 29th September 1864, Farrar’s homily concerned ‘the angels of God’, but he spoke not of corporeal angels as we find in Stanhope’s pictures, but of angels as metaphors for ‘the crises in human

life which come as [God’s] messengers’: nothing in the sermon relates to the subjects in the pictures created over a decade later. It is more fruitful to assume that the details of the series took shape in the light of discussions between Stanhope, Farrar, and not least, Bodley and Garner. Indeed, the earliest historian of the ‘New Chapel’, Newton Mant, writing in 1889, recalled that ‘when Mr. Spencer Stanhope was commissioned to paint these pictures it was stipulated by the architects that they were to be as decorative as possible, that being the chief object for which they were required.’ That Stanhope exercised a degree of autonomy in the choice of subjects, however, is suggested by an enquiry from Bodley in the early summer of 1878, in which he asked the painter what the themes of the next pictures would be. In answering his query, Stanhope provided the complete list, albeit in a jumbled order:

7. ‘ The Annunciation’

8 . ‘ The Nativity’

In undertaking what would be the largest project of his career, Stanhope worked on several canvases simultaneously, batching them off to the College in pairs as he progressed through the scheme. The first two pictures were delivered to Marlborough from the artist’s London studio during the Christmas vacation of 1875-1876. Their arrival was heralded by a letter to the Bursar dated 21st November, in which the artist announced ‘I am glad to be able to inform you that two of the pictures for the Chapel, The Sacrifice of Isaac and Hagar & Ishmael, are now completed with the exception of a little gilding and touching up which I shall finish next week when I return to town. I am writing to Bodley about the frames and as soon as they are ready the pictures

can be sent down.’ When Stanhope left England to winter in Florence at the end of 1875, he took four unfinished canvases with him, setting them up in his studio in Villa Nuti, and completing two of them there. The pictures, ‘The Annunciation’ and ‘The Gloria In Excelsis’, reached Marlborough in the late spring of 1876, and were mounted on the walls of the Chapel by the end of the summer. In the following February, the group on show had grown to six, with ‘The New Jerusalem’ and ‘The Sepulchre’ (sometimes referred to by Stanhope as ‘The Entombment’) arriving over the Christmas break. At that point the trickle of pictures dried up, with no further paintings arriving for the next eighteen months. But Stanhope had not been idle, and in

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

(Shepherds)

12. ‘ The New Jerusalem’

4. ‘ The Sacrifice of Isaac’

3. ‘Hagar in the Wilderness’

11. ‘The Entombment’

2 . ‘Abraham and the Angels’

5. ‘Lot Leaving Sodom’

1. ‘ The Expulsion’

6 . ‘ The Holy Children in the Furnace’

10. ‘ The Agony in the Garden’

22

9. ‘ The Temptation’

Villa Nuti

June 1878 wrote that ‘six pictures start today for Marlboro. I shall be very anxious to hear of their safe arrival as I look upon it rather as a venture sending them all at once.’

The final batch of canvases duly arrived at the College unharmed, but were received with dismay. Two in particular offended Farrar’s replacement as Master, George Bell: ‘The Expulsion from Eden’ and ‘The Three Holy Children’. Criticism surrounding the latter concerned perceived deficiencies in Stanhope’s draughtsmanship, which the artist admitted had suffered ‘when I happened to be a little out of sorts with asthma.’ But the dissatisfaction with the scene of Adam and Eve driven from Paradise was so absolute that the College flatly rejected it. Upon hearing of the refusal, Stanhope confessed to Bodley, ‘I am sorry, not to say disappointed. I had hoped that the expulsion would have been popular. However, it is not so & of course I will take it back at once.’ The chief objection seems to have been the appearance of the Archangel Michael wielding a fiery sword, damned by one precocious critic in The Marlburian as ‘that angel in armour of Henry II, [and] Anglus non Angelus’ (‘An Englishman, not an angel’). The College was also unhappy with the colour of the wall engirdling the Garden of Eden, which Stanhope had painted as blocks of red marble, while the College authorities preferred it to be white. But it is hard to escape the suspicion that the real offence arose from Stanhope’s representation of

23

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Eve fleeing Eden in a state of seminakedness, her streaming red hair failing to conceal her upper form. Stanhope, stung by the rejection, grumbled to Bodley about the gulf ‘that separates what Tom Taylor calls honest healthy English art and productions of the Great (to me) Florentine Masters.’ Taylor, the art critic of The Graphic in the 1870s and hostile to Pre-Raphaelitism’s continental sympathies, was a foghorn advocate of a nationalist English style. The injured Stanhope put down the experience as a ‘memento dipingue more Britannico’ – a reminder to paint in the ‘British manner’.

The rejection of ‘The Expulsion from Eden’ put back the College’s plans to unveil the full suite of pictures on Prize Day, 1879. Photographs of the interior of the Chapel from that time show eleven of Stanhope’s pictures in situ with a blank space left for the missing ‘Expulsion’. The second version of the picture was at last in place by October of that year, bringing the cycle to a close. Another critic from The Marlburian, writing under the cipher ‘R’, thought that the new ‘Expulsion’ ‘does not to us present much originality of treatment. The left hand portion of the canvas is occupied by four figures of angels, draped gracefully, (but as regards colour, daringly), and in attitudes somewhat stiff and formal.’ What ‘R’ observed was Stanhope’s replacement of the figure of St Michael with a cast of four angels who guide Adam and Eve through Eden’s portals; the same critic did not comment upon Eve’s new position

on the farther side of Adam, shielding her from the searching gaze of the boys. The College’s anxieties about the original image were allayed, but Stanhope’s confidence in his initial design was unshaken. Although we do not know the fate of the canvas rejected by Marlborough, two other pictures following the original composition were exhibited by Stanhope, one in tempera, watercolour, and pencil in the later 1870s, and the other the large and magnificent canvas from around 1900 that constitutes one of the treasures of the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. The Liverpool picture, a colourist fantasia with fierce magentas, olive greens, and superfluity of decorative effects, pushes the painterly arts towards the realm of tapestry.

The College community did not have many years to enjoy Stanhope’s pictures in their places along the walls of Blore’s Chapel. The need for a larger space for collective worship had become urgent by the early 1880s, and the old building duly came down in 1884 to make way for the magnificent edifice we cherish today, designed by the indefatigable Bodley and Garner. It was always part of Bodley’s plan that the ‘The Ministration of Angels on Earth’ should be preserved for the new building, securely integrated within panelling in dark wood and parcel-gilt. In June 1884, Bodley informed the Bursar that Stanhope had offered to take the paintings with him to Florence to retouch them and make improvements, charging the College only for the cost of carriage.

24

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Among the problems Stanhope wished to address was damage done to the surface of the pictures by their proximity to the old Chapel’s gas-burners. Stanhope took at least some of the canvases with him on his travels over the next three years, shipping them from Italy to Brighton when he took the sea-cure there, and to a health resort at Turin when an epidemic hit Florence; he also reported to Bodley that the pictures had survived two earthquakes while in his hands. Partly for these reasons, progress on the retouching was slow, and Stanhope was only able to promise the return of five of the canvases by the end of 1885. As the months passed, the Bursar grew restive as the pictures remained in Italy, despite the College’s desire to have them all in place for the service of dedication of the new Chapel on 29th September 1886. In the event, only five pictures were in place for the ceremony, and the seven yawning gaps along the walls had to be covered by fabric hastily chosen by Bodley barely a week before the service. Despite the panic, the pictures that were on show looked well in their new surroundings, and the Bursar sent Stanhope a ‘pleasant letter’ conveying his appreciation for his work. The artist acquitted himself of his duties to the College in 1887, returning four of the pictures in April, and the final three in June.

It is remarkable to look back across almost 150 years at the reactions the series provoked among the Marlborough community, both upon its first appearance in the 1870s, and re-emergence in the

1880s. As Newton Mant sadly observed in 1889, ‘the pictures […] have received a good deal of criticism, most of it, in the writer’s opinion, both unappreciative and unjust.’ Much of this criticism was lost upon the air as soon as it was uttered in conversations that evidently animated the pupil body and Common Room alike. But some of it was committed to print in The Marlburian, which at that date was published on a termly basis. The most regular commentator was the aforementioned ‘R’, William Spry Robinson, a junior scholar and future assistant master at Wellington College, who offered observations on the works based upon art-historical comparisons as they arrived piecemeal between 1876 and 1879. Less astute was a certain ‘W. V. B.’ who improbably likened ‘Lot Rescued from Sodom’ to ‘an uncomfortable feeling like what you experience when jammed in a low old-fashioned railway carriage with a crowd of people, with no room for your legs and with your head touching the roof.’ But it was not only amateur critics who joined the debate; the professionally concerned also weighed in, including one agitated by what we might term the gender-ambiguity of the angelic forms. Such androgyny presented a challenge to the ideals of muscular Christianity, the prevailing ethos that had become firmly embedded in the country’s public schools. As an anonymous reviewer for the respected architectural journal The Builder sniffed, ‘We should have preferred that English boys should see before them in a chapel

something more manly than Mr SpencerStanhope’s [sic] weak and superstitious sentimentalities; but we suppose that is not our business.’

It is difficult to find common ground with views and prejudices expressed in a culture very different from our own. But it is also hard to recapture the sense of shock Stanhope’s pictures elicited among their first viewers in the 1870s. Displayed in the august setting of a chapel in an English country school, these paintings must have seemed radical, cutting-edge, even unsettling. To our eyes, Stanhope’s paintings stand as vibrant representatives of the Pre-Raphaelite idiom: solemn, poetic, and wistful. But in the 1870s, Stanhope championed a style still redolent of bohemian rebellion and progressive modernity, an artistic vision that ‘sparkled like radium in the leaden tube of Victoria’s reign’, as one critic has described it. The innovations in visual language and subject matter that were eventually to win out in European painting – Impressionism, Pointillism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and the rest, were then either only emerging (Monet’s ‘Impression, Sunrise’ dates from 1872) or lay years in the future. Regardless of what might be current in Paris, what counted as new and modish in British art was work of the kind exhibited on the walls of the Grosvenor Gallery, of which Stanhope’s was a prime example. To conservative taste, his intense polychromy, compositional compression, cast of curiously detached figures, and

weird, unworldly landscapes seemed alien to the established canons of art. Contrastingly, within the contexts of Pre-Raphaelitism, the Aesthetic Movement, and the wider European Symbolist style, Stanhope’s work holds a distinctive and honoured place.

We can afford to be more generous to Stanhope than our Victorian forbears proved to be. Over the past fifty years, Stanhope has been subject to sympathetic reassessment, and restored to his rightful place in the history of British art. His work in Marlborough College Chapel is recognised as simply the largest and most splendid Pre-Raphaelite pictorial cycle to be found in any British school, unrivalled in its rich and sumptuous palette, dreamlike Italianate settings, and stately, dignified actors, whether divine, angelic, or mortal. Speaking to a modern age possessed of fewer certainties, Stanhope’s series moves us deeply for its high moral purpose, belief in providential order, and conviction in the power of art to influence and improve lives. Perhaps most of all, Stanhope’s images of ministrations from on high remind us of the cultured vision shared by a rare generation of educators that led this community a century and a half before us, animated by a lowly sense of service yet guided by the highest of ideals.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

25

Stanhope’s Variants

Conscious that work carried out for a private Chapel was unlikely to be known much beyond its walls, Stanhope felt justified in revisiting a couple of the themes from the Marlborough series and offering them to the wider public. The two subjects he returned to were ‘The Expulsion from Eden’ and ‘The Sepulchre’. Of the former, Stanhope painted at least four versions, the one extant at the College; the original version refused by the College and now lost; a small watercolour, pencil, and tempera version in private ownership; and the large, imposing tempera canvas now at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. This last-named has sometimes been thought to be the picture rejected by the College, but its larger scale, wholly different stylistic idiom, and much later date, disprove the claim. Closer in time to the execution of the College’s version of ‘The Sepulchre’ is the fine version of the subject now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney. Renamed by Stanhope ‘Why Seek Ye the Living Among the Dead?’, this painting closely resembles the Marlborough original, although it lacks the gilded passages found in the College version. A much smaller rendering of the same scene appeared on an altarpiece Stanhope designed for Holy Trinity, the Anglican church in Florence. Dating to the early 1890s, this work was dismantled and sold in the mid twentieth century.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 26

Top right: John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, The Expulsion from Eden, c.1877.

Bottom right: John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Why Seek Ye the Living Among the Dead?, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Opposite: John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, The Expulsion from Eden, 1900, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

The Expulsion from Eden

Date:

c.1878-1879; retouched 1884−1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions: 168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Genesis 3, 23-24

Inscription:

Ne reminiscaris Domine delicta nostra ‘Remember not, O Lord, our transgressions.’

Source of the inscription: The Antiphon of the Seventh Penitential Psalm

Note: Adam and Eve are expelled through the gates of the Garden of Eden by four angels, described in the Bible as ‘Cherubims’. The foremost Cherubim, in robes of red, carries a flaming serpentine sword, his expression stern and forbidding. The other Cherubims appear more sorrowful. Adam buries his face in his hands, while Eve clings fearfully to his shoulder. Within the walls of Paradise the roses bloom and the ground is dotted with flowering plants and pebbles of precious gems. Outside its gates lies the Fallen world under a dark and ominous sky; here the earth is strewn with barren stones. Stanhope loosely based his figures of Adam and Eve upon Masaccio’s fresco of ‘The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden’ painted around 1425 for the Brancacci Chapel in S. Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 28

1

Abraham Entertaining the Angels

Date:

1877-1878; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Genesis 18, 1-16

Inscription:

Adjutorium nostrum in nomine Domini

‘Our help is in the name of the Lord.’

Source of the inscription:

Biblia Sacra Vulgata , Psalm 123, 8

Note: Abraham stands at the door of his tent in the plains of Mamre and serves food to angels who have appeared to him, according to Genesis, in the form of ‘three men’. The angels have come to announce that Abraham will have a son by his wife Sarah, despite both being ‘old and well stricken in age’. Among the beautiful interplay of hands, the leftmost angel gestures towards the open door of the tent in which Sarah is hiding, emphasising the story’s typological parallel with the Archangel Gabriel’s annunciation to the Virgin Mary depicted across the Chapel aisle. That child, Jesus, will of course stem from the line of Abraham. In true Pre-Raphaelite style, the tent stands as a symbol of the womb that shall bear the providential child.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 30

2

Lot Rescued from Sodom

Date: 1878; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions: 168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Genesis 19, 15-30

Inscription:

Nos qui vivimus benedicimus Domino

‘We that live bless the Lord.’

Source of the inscription: Biblia Sacra Vulgata , Psalm 113, 26

Note: Two angels lead Abraham’s nephew Lot and his two daughters from Sodom to spare them from the fire and brimstone God unleashes upon the city, angry at the wickedness of its inhabitants. In a linear composition reminiscent of a classical frieze, the figures process across the canvas with tragic pathos, the foremost angel leading the party with a firm, purposeful expression, the crook of his arm echoing that of Lot at the rear of the group. The two daughters seem to reflect on their precarious position, and the bundle cradled in the arm of the leading daughter foreshadows the shameful offspring both sisters will engender from their father. The dangers of other sins of the flesh are luridly emphasised by the flaming skyline of Sodom seen to the rear.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 32

3

Hagar in the Wilderness

Date:

1875; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Genesis 21, 14-20

Inscription:

Ego te potavi aqua salutis de petra ‘I gave thee the water of salvation from the rock.’

Source of the inscription: Improperia , Antiphon 6

Note: Hagar, an Egyptian handmaid to Sarah, bore Abraham a son, Ishmael. When the aged Sarah gave birth to Abraham’s rightful heir, Isaac, Hagar was banished with her child into the wilderness of Beersheba. With her few rations spent, she ‘cast the child under one of the shrubs […] and sat her down over against him a good way off, as it were a bowshot; for she said, “Let me not see the death of the child.” And she sat over against him […] and wept.’ Stanhope shows the angel of God comforting the sobbing mother, laying his hand upon her shoulder and pointing towards a spring. The young shrub that rises around the exhausted body of Ishmael symbolises the rich progeny promised to him by God: ‘for I will make him a great nation […] And God was with the lad; and he grew, and dwelt in the wilderness’.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 34

4

The Sacrifice of Isaac

Date:

1875; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions: 168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Genesis 22, 1-18

Inscription:

Semen ejus haereditabit terram

‘His seed will inherit the earth.’

Source of the inscription:

Biblia Sacrum Vulgata , Psalm 24, 13

Note: An angel in sumptuous saffron and vermilion robes stays the hand of Abraham as he is poised to sacrifice his son Isaac in unquestioning obedience to God. Having passed this trial of faith, Abraham is spared the loss of his son, and the angel points to a ram caught in a thicket that will take Isaac’s place on the altar. According to typology, in just such a way, Christ, the Lamb of God, will take our place in repaying the price of sin. Stanhope’s composition depends upon the strong horizontal emphasis of the angel, the bound Isaac, and carefully observed logs that make up the altar. The arid landscape of the land of Moriah recalls the strange rocky scenery favoured by Leonardo.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 36

5

The Three Holy Children

Date:

1878; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: Daniel 3, 1-30

Inscription:

Si ambulavero in medio tribulationis vivificabis me

‘Though I walk in the midst of trouble, thou wilt revive me.’

Source of the inscription:

Biblia Sacra Vulgata , Psalm 137, 7

Note: The story from the Book of Daniel tells of three Jewish men living in Babylonian exile, Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego, who, as worshippers of the True God, refuse to bow down before a golden image raised up by King Nebuchadnezzar. Insulted by their refusal, the king orders that they be cast into a fiery furnace, and the young men, officials at Nebuchadnezzar’s court, are ‘bound in their coats, their hosen, and their hats, and their other garments’ and thrown into a fire stoked to be sevenfold hotter ‘than it was wont to be heated.’ The king is therefore astonished to see the men moving around amidst the flames in the company of a fourth figure ‘like the Son

of God.’ When extracted from the flames, the three men are found to be utterly unharmed, with not so much as a singed hair nor trace of smoke upon their clothes. Nebuchadnezzar acknowledges that God ‘hath sent his angel, and delivered his servants that trusted in him’ and rewards the men with further honours. Stanhope’s image departs from the strict terms of Daniel’s text, rendering Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego as children, when the story refers to them as ‘these three men’. The painter was perhaps thinking of the trio’s appearance in the opening chapter of Daniel when they are described as ‘children in whom was no blemish, but well favoured, and skilful in

all wisdom, and cunning in knowledge, and understanding science, and such as had ability in them to stand in the king’s palace’. Another departure concerns the boys’ clothing, which in the College picture are simple tunics, not the coats, hosen, and hats mentioned in the Bible. The angel’s distinctive posture, in which he extends his arms to throw a protective mantle around the boys, is a conscious borrowing of the iconography of the Virgin of Mercy, a popular devotional subject in medieval and Renaissance art, and which Stanhope knew from Piero della Francesca’s ‘Maria della Misericordia’ (early 1460s) in Sansepulcro, near Arezzo, Tuscany.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 38

6

The Annunciation

Date: 1876; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions: 168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: St Luke 1, 26-38

Inscription: Ave Gratia plena. Dominus tecum ‘Hail, full of grace. The Lord is with thee.’

Source of the inscription:

Biblia Sacra Vulgata , St Luke 1, 28

Note: The Archangel Gabriel greets the Virgin Mary, extending his right arm in salutation, while Mary, kneeling in prayerful attitude, modestly lowers her gaze. Overhead, the Dove of the Holy Spirit descends in streaming radiance from heaven. The scene is rich in symbolism. The white lily held in Gabriel’s left hand signifies Mary’s bodily and spiritual purity, while the enclosed garden behind the low wall refers to the Hortus conclusus, symbol of the sanctity of the Virgin’s womb. The tall building to the right is Mary’s dwelling in Nazareth, but acknowledges one of Mary’s mystical identities in the Litaniae Lauretanae as Domus aurea (‘House of Gold’); likewise,

the rose bush recalls Mary as Rosa mystica. This shrub also links with the rose bush of similar appearance across the aisle in ‘The Expulsion from Eden’, reminding us that Christ comes as a Second Adam to redeem us from the sin of the First. The stems of the roses anticipate Christ’s death and the crown of thorns, a reflection deepened by the cypress trees, traditional ciphers of death, and believed in some traditions to have been the tree that provided the wood for the cross. Stanhope’s picture is heavily indebted for its composition to Leonardo’s early masterpiece, ‘The Annunciation’ (early 1470s) which the artist had studied in the Uffizi, Florence.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 40

7

The Gloria In Excelsis

Date: 1876; retouched 1884-1886

Materials: Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions: 168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: St Luke 2, 8-20

Inscription:

Hodie in terra canunt angeli, laetantur Archangeli

‘Today on earth the angels sing, the Archangels rejoice.’

Source of the inscription:

Antiphon to Hodie Christus Natus Est

Note: Three angels appear in the sky above a shepherds’ enclosure. The central angel, in robes of gold, is dramatically foreshortened, while the two angels to each flank are clad in coral-coloured garments, their faces in profile. The three shepherds within the wattle fence react with astonishment at the heavenly visitation, with the oldest in the centre raising his arm to shield his face with his cloak. The angels hold between them a long banderole, and with lips parted, sing the text we see inscribed on it in uncial font: ‘Gloria In Excelsis Deo:

Et In Terra Pax Hominibus Bonae

Voluntatis’ (‘Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to men of good will’). The fallen world Christ has come to save is reflected in the sombre, tertiary colours of the lower part of the picture, and contrasts with the rich glories of the heavenly host. The angels carry small flames issuing from their foreheads, in reference to the ‘cloven tongues like as of fire’ manifest upon the heads of the Apostles at the first Pentecost (see Acts 2), but also found in depictions of angels by Stanhope’s great hero, Fra Angelico.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 42

8

The Temptation of Our Lord

Date: 1878-1879; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: St Matthew 4, 1-11

Inscription:

Custodiant te in omnibus viis tuis ‘To keep thee in all thy ways.’

Source of the inscription: Biblia Sacra Vulgata , Psalm 90, 11.

The full text reads ‘For he shall give his angels charge over thee: to keep thee in all thy ways.’

Note: The narrative of the Temptation of Christ is told twice in the Gospels, by St Matthew and St Luke, but only St Matthew mentions that ‘angels came and ministered unto him.’ The period of forty days and forty nights Christ spends in the wilderness preparatory to his ministry is punctuated by visitations from Satan who seeks to deflect Jesus from his great mission by offering him temptations. The nature of these infernal allurements is hinted at in the desolate, mountainous landscape: for Christ to turn stones into bread; to throw himself off a high place; and to enjoy dominion over the earth in return for kneeling before Satan. Christ’s steadfast resolve causes Satan

to gnaw his fist in frustrated fury in the gorge to the bottom left. But the ordeal has taken its toll, and Stanhope shows Christ as gaunt, exhausted, and weak, having endured rigorous self-denial in resisting the wiles of the Devil. The ministering angels, beautifully harmonious in madder robes with delicate gold filigree decoration on shoulder, chest, and cuff, look pensive and sad, almost as if they can foresee in Christ’s enfeebled form his lifeless body taken from the cross. The impish figure of the Devil is inspired by similar devils and demons found in the work of Sandro Botticelli, such as his ‘Mystic Nativity’ (c.1500) in the National Gallery.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 44

9

The Agony in the Garden

Date: 1877-1878; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: St Luke 22, 39-46

Inscription:

Deus, Deus meus respices in me

‘O God, my God, look upon me.’

Source of the inscription:

Biblia Sacra Vulgata , Psalm 21, 2

Note: Stanhope’s deliciously coloured painting illustrates the episode told in the Gospels of St Mark and St Luke of Christ’s agonised prayers in the Garden of Gethsemane prior to his arrest and trial. Stanhope takes his account from St Luke, as only he mentions that ‘there appeared an angel unto [Christ] from heaven, strengthening him. And being in agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground.’ Christ’s chosen disciples, St John, St James, and St Peter, lie asleep to the left, the last-named leaning against a rock which punningly alludes to his name in Latin – Petrus. Christ lifts his hands to his Heavenly Father, asking to forgo the sufferings of the Passion shortly to befall him. An angel

kneels before him, holding a cloth under Christ’s head to catch drops of blood. In the left background we see a path winding towards higher ground; there three thin trees stand on a plateau, their boughs spread like the crosses soon to be raised on Calvary. The horizon is filled with darkening trees, some the umbrella pines more typical of Italy than Judaea, and others, funereal cypresses. A gap in the trees reveals the last rays of the evening sun as the night, like Judas and his Roman masters, closes in. Yet in this moment of dread and foreboding, the artist allows for a sense of hope: while Christ kneels on barren, obdurate rock, the angel kneels on greensward spangled with flowers. One symbolizes the stony tomb, the other, the new life that lies beyond it.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 46

10

The Sepulchre

Date:

1876-1877; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage: St Matthew 28, 1-8

Inscription:

Nolite timere, Scio enim quod Jesum quaeritis

‘Fear not ye: for I know that ye seek Jesus.’

Source of the inscription: redaction of Biblia Sacra Vulgata , St Matthew 28, 5

Note: The scene depicts the arrival at Christ’s tomb on Easter morning of the Three Marys: Mary Magdalene, Mary, the Mother of James, and Mary of Clopas, sometimes collectively known as the Myrrhbearers (Myrophorae). We see the women greeted by the Angel of the Resurrection who wears white robes covered with a surplice of green, traditionally the symbolic colour of Hope. Among the women, the Magdalene is identifiable by her attribute of the alabaster perfume-jar; Mary, the Mother of James stands in the centre with her arms stretched out in appeal; and Mary of Clopas, closest to the angel, kneels with hands clasped, gazing up mournfully at the divine messenger. Stanhope traces the women’s anxiety, confusion, and pious submission through the gently declining arc described by their bodies.

According to Stanhope’s source, the Gospel of St Matthew, the angel tells the women, ‘He is not here: for he is risen, as he said. Come, see the place where the Lord lay. And go quickly, and tell his disciples that he is risen from the dead’. The angel’s commanding gesture confirms that Christ is no longer to be found in this rocky, arid place; instead, he has sprung up to new life like the flowers carpeting the grass around the angel’s feet. New growth can also be seen in the flourishing branches sprouting from the hollowed-out olive tree to the left, a fitting emblem since Christ has triumphed over the trials and sufferings that began among the trees of the Garden of Gethsemane on the slopes of the Mount of Olives.

Stanhope was conscious that this painting represented one of the strongest of his series. He repeated the theme and

composition on at least two occasions, once in a full-scale variant copy painted in 1877 without the expense of gilding, now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney; and the other, smaller in scale and differing in composition, on the predella of an altarpiece painted for Holy Trinity, the Anglican church in Florence, between 1892 and 1896. Unfortunately, this altarpiece was deemed irredeemably unfashionable by the mid-twentieth century, and consequently taken down, broken up, and its elements sold off, with the consequence that the current whereabouts of the predella is unknown. Stanhope’s full-scale study for the altarpiece, which for many years graced the interior of Christ Church, Esher, in Surrey fared little better, being deaccessioned from the church by the Diocese of Guildford and passed to Christie’s for sale in 2016.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 48

11

The New Jerusalem

Date:

1876-1877; retouched 1884-1886

Materials:

Oil, gesso, gold leaf on canvas

Dimensions:

168 x 127cm

Biblical passage:

Revelation 21, 1−27

Inscription:

Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua

‘Heaven and earth are full of thy glory.’

Source of the inscription: The Sanctus of the Ritus Romanus.

Note: St John the Divine kneels in awe before the vision of the New Jerusalem descending from the heavens. He is granted this revelation by an angel in garments of madder and veridian and bearing a ‘golden reed’, a measuring rod by which the dimensions of the city are taken and recorded. The city is contained within four long walls, and with three portals on each side, a total of twelve. Over its ramparts rise buildings of unparalleled magnificence: domes, towers, steeples, and bastions, all in dazzling gold. Through the gateways in its flanks, we glimpse golden streets; overhead, golden bells swing joyously in a golden belfry. By contrast, the temporal world below sinks into oblivion, the mighty sun slipping below the horizon of a glassy sea margined by desolate and barren rocks. In his depiction of the New

Jerusalem, Stanhope was loosely influenced by the idealised classical architecture painted in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s fresco ‘The Arrival of Cardinal Gonzago’ in the Camera degli Sposi, in the Ducal Palace, Mantua (1465−1474), although he crams more buildings within Heaven’s walls, a fantastical agglomeration of types from Rome, Florence, and Urbino.

In his rendering of the city, he simplifies the decoration described in Revelation, where the walls are said to be encrusted with precious stones, pearls, and crystal. In Stanhope’s vision, the Heavenly City presents a dazzling spectacle of gold. That the painter was inspired by William Morris to envision a new social order here on earth – as has been argued –seems uncertain.

Stanhope returned to this pictorial theme some twenty years later when a similar scene of the New Jerusalem formed the central panel of a reredos he painted for All Saints, Putney, a church also enriched with windows by Burne-Jones and Morris.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 50

12

A Note on Stanhope’s Materials

Stanhope painted the twelve pictures of ‘The Ministration of Angels on Earth’ in oil on canvas, but there are some technical peculiarities to his work that are worthy of comment.

Always a restless innovator, Stanhope switched his methodology midway through the series, painting the final six canvases in the technique known as alla prima , or the wet-in-wet method. This technique, much loved by the founding Pre-Raphaelites William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, involved applying pigment to a wet ground of white paint in the pursuit of heightened luminosity of colour. In modern painting, the wet-in-wet method is regarded as a time-saving device, since the artist does not need to wait for the foundational layers to dry before adding new pigment; in Pre-Raphaelite art, however, it was a slow and painstaking approach, since painters tended to operate on only one very small area of the canvas at a time.

Another peculiarity of the Marlborough paintings are the raised areas in low relief that appear in all the pictures, generally on the wings and halos of the angels, and the

halos of Christ and saints, but in other details, too, such as the rod borne by the Angel of the Apocalypse. These raised areas, known as pastiglia , were created by building up and modelling gesso, artists’ plaster made from chalk and rabbit-skin glue. Stanhope did not carry out such specialist work himself because by Victorian times such skills had largely devolved to the workshops of professional frame-makers. When in London, Stanhope used the firm of William Augustine Smith of Mortimer Street, while in Italy he employed a man called Collins from among the English émigré community. The technique they used was to apply so-called Armenian bole, red clay bound with animal glue, to the raised areas of gesso to serve as a ground for the gilding. Gold leaf was then applied to the pastiglia and partially rubbed back to reveal the lower red substrate, an effect seen particularly clearly on the angels’ wings in several of the Chapel paintings.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 53

Stanhope’s Secret Language of Flowers

Aware that the Chapel paintings would be mounted over the heads of worshippers and typically viewed from a distance, Stanhope bestowed a monumental quality upon their compositions.

Marlborough

Art and Vision 55

College Chapel:

However, he did not abandon his principles as a Pre-Raphaelite, and included many finely painted details that can only be fully appreciated at close quarters. These are exemplified by the microscopically observed studies of flowers which appear in five pictures of the series. Remarkably, Stanhope incorporated almost 250 individual flowers, not to mention some 120 trees and herbs in these works. His intricate rendering of petals, stems, leaves, and grasses amply attest to the artist’s relish for the natural world.

Interest in flowers went to the core of Pre-Raphaelite art. Both Rossetti and Morris consulted prized seventeenthcentury copies of John Gerard’s Herball as reference works, and the flowers in Millais’s ‘Ophelia’ were so true to life that a professor of botany brought students to the Tate to see them. However, it was not the scientific aspect of flowers that engaged painters so much as their symbolic properties. Medieval authors had invested flowers with a multitude of

56

meanings, believing that God had created nature as a book, the Liber Naturae, readable through its symbols. Under the influence of the Gothic Revival there was a desire to recover this lost language, and numerous guidebooks were published to help nineteenth-century readers identify the hidden encodings of flowers, and how they served as emblems of virtues, vices, emotional states, or other abstract qualities. The most popular of these publications, Henry Phillip’s Floral Emblems (1825) and Robert Tyas’s The Sentiment of Flowers; or Language of Flora (1836), ran to many editions. The knowledge such books imparted, known as ‘floriography’, caught a firm hold on the Victorian imagination, and informed the creative practices of many artists.

Some of Stanhope’s flowers in the Marlborough paintings reflect the influence of floriography. In ‘The Expulsion from Eden’, for example,

the Fall of Man is amplified by the presence of violets (short-lived beauty), Herb Robert (foolishness), and purpletinged pansies (repentance). In ‘The Sacrifice of Isaac’, Abraham’s obedience to God finds an echo in the lily-of-thevalley and harebells, respectively associated with humility and faithfulness. In ‘The Annunciation’, the lilies held by the Archangel Gabriel represent Mary’s purity, whereas the dog-rose suggests her ‘joy mingled with pain’ on hearing the angel’s message. Amidst the rich sward in ‘The Agony in the Garden’ we find oxeye daisies (patience), pink anemone (Christ’s blood), zinnia (endurance), dandelion (perseverance), and yellow iris (hope). Likewise, in ‘The Sepulchre’ the grass nurses numerous tulips in red and white (the colours of the Resurrection), the yellow pansy (joy), hyacinths (forgiveness), and windflowers (rebirth). The inclusion of such floral metaphors contributes to the overall beauty of Stanhope’s paintings while deepening their spiritual significance.

57

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

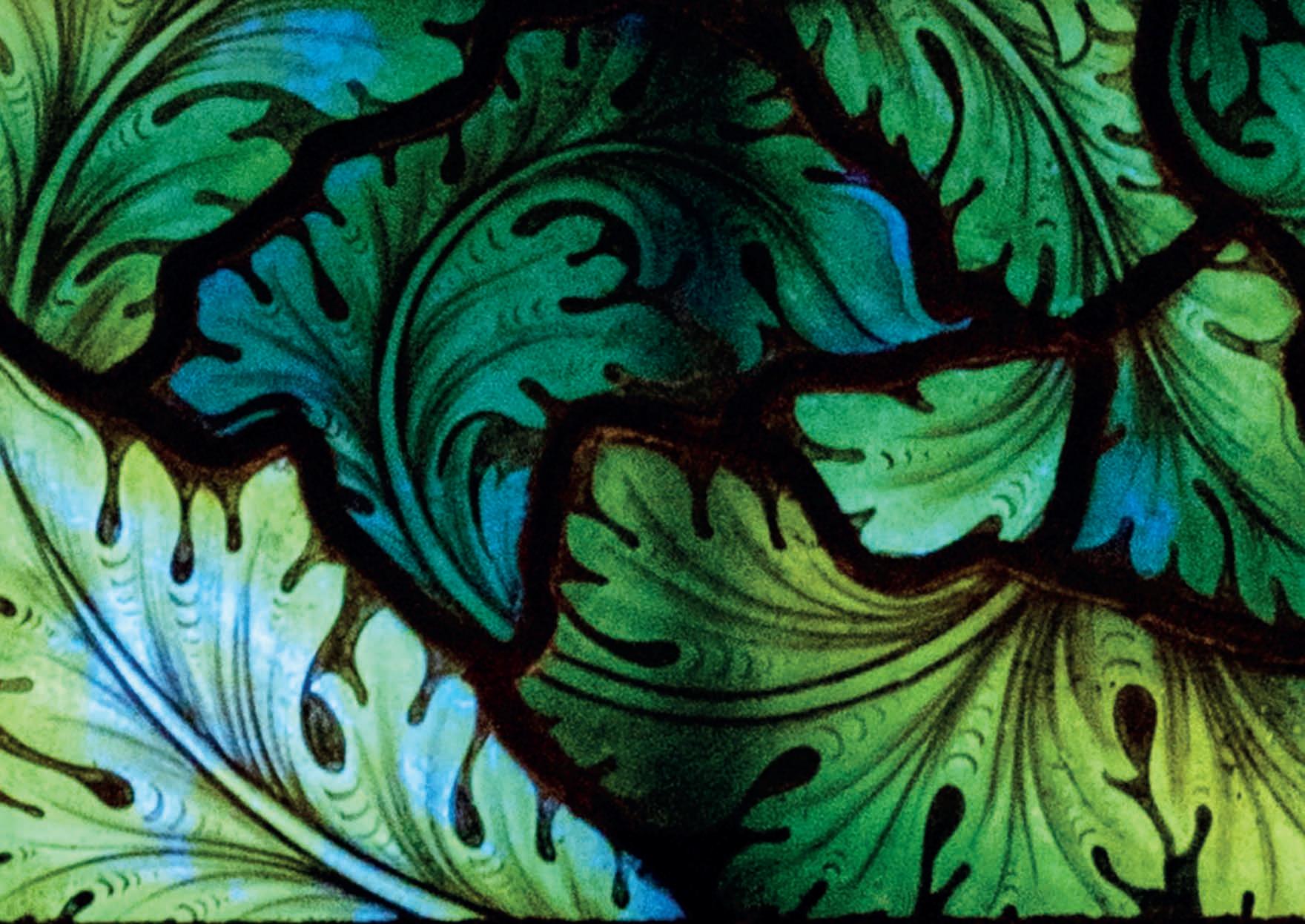

The Decorative Woodcarving

William Wilmut (second from right) in his workshop, c.1890

William Wilmut (second from right) in his workshop, c.1890

When Stanhope’s paintings were first mounted upon the walls of Blore’s Chapel in the 1870s, they were fitted into frames with narrow side rails and somewhat ungainly coves projecting over their upper parts. Some, though not all, bore carved and gilded Latin inscriptions on their lower rail. None of this work was preserved for the new Chapel since its larger scale required an expanded scheme of interior panelling. To carry out this work, Bodley turned to the Bristol firm of Stephens and Bastow, a highly experienced building company with expertise in ecclesiastical furnishing. Their principal woodcarver William Henry Wilmut (1847-1911) led the team allotted to cover substantial parts of the Chapel’s lower bays with metre after metre of high- and low-relief panelling, all done in dark-stained oak and parcel-gilt with consummate virtuosity and artisanal pride. Everywhere the eye falls there are details that delight, from the stately textualis quadrata font of the inscriptions, to the exuberantly fluid vegetal motifs. Symbolism abounds, so we see Eucharistic ciphers in the running vines and

wheatears, the message of peace in the branches of olives, the Resurrection figured in pomegranates bursting with seeds, and the Virgin’s sanctity in the flourishing lilies.

Hanging from carved boughs or serving as punctuation points throughout the panelling are many small shields enriched with devices. Some carry universal Christian symbols, such as the Chi Rho, Pelican-in-its-Piety, Eucharistic chalice, or IHS or Fish ciphers for Christ. Others celebrate the College’s individual houses, like C1’s cross pattée, C2’s fleur-de-lis, C3’s mitre, B1’s crossed arrows, Cotton’s crossed sword and key, Preshute’s crescent and star, Barton Hill’s Star of David, and Littlefield’s scallop shell, as well as the devices of Houses long since disbanded, but whose symbols have been repurposed as Mill Mead’s rose, Elmhurst’s anchor, or the cross moline of Morris.

More substantial shields feature in the two handsome panels mounted to each side of the west door, one on the south side standing sentinel over the seat

59

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

60

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Marlborough

and Vision 61

College Chapel: Art

reserved for the Master, and the other on the north side over the place originally reserved for the College Bursar. In the Master’s panel three angels support a shield bearing the College arms, except that the text displayed on the Bible offers not the familiar Pauline injunction from Corinthians, but the opening verse of St John’s Gospel: ‘In Principio erat Verbum, et Verbum erat apud Deum, et Deus erat Verbum’ (‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’). The general composition of angels bearing up a shield is mirrored in the panel over the Bursar’s seat, although here the shield displays the Virgin as Queen of Heaven, or Regina Caeli, with crown and sceptre, and holding the Christ Child. Uniting both panels is the exceptional degree of skill in their carving and ornament, such as the folds of drapery, curls of angelic tresses, clean lines of the aedicula, or rich diaper-work patterning over the tinctures of the heraldic fields.

Wilmut, a pious man who led the choir in his local church in Bristol, was soon to branch out on his own, setting up as ‘Wm. Wilmut and Sons, Architectural Carvers in Wood, Stone, and Alabaster’ in 1889: he later returned to the College to furnish the Garnett Room with its gallery and spiral stairs. Another gallery, the National Gallery, was to receive doors made by his hand in 1887, part of a general refurbishment that saw the addition of its grand staircase, another project undertaken by Stephens and Bastow. In surveying the virtuosity of Wilmut and his carvers, gilders, carpenters, and tinters, we are struck by how fully they embodied William Morris’s ideals concerning the essential dignity and spiritual value of craftsmanship, and its capacity to elevate manual tasks to superlative degrees of artistry in the service of God and man.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 63

Looking back at Stanhope

The twelve canvases in Stanhope’s great series at Marlborough manage to be both uniform and diverse. Certainly, there is great visual variety for the eye to linger on, and it was this richness of imagery that I grew to love in the many hours spent in Chapel during my five years at Marlborough.

One quickly notices the tension between the narrative and the decorative throughout Stanhope’s paintings: while his subjects are serious themes from the Bible, his treatment of them tends towards the ornamental, graceful, and stately. Moreover, Stanhope’s palette is surprisingly bold but harmonious, an effect achieved through his balanced repetition of hues throughout the series. He was obviously careful to present his figures, some forty-five in all, at a consistent scale, so that while inhabiting their own individual narratives, they come together to contribute to the visual world of a greater whole.

The layout of Marlborough’s Chapel obliged me to spend a long time studying Stanhope’s canvases. Looking from one’s pew across the aisle, the option was to stare into the rows of largely blank faces opposite, to catch the eye of a member of Common Room in the stalls of the upper tier or look a little higher at the colours and lines of Stanhope’s sumptuous canvases. It was an easy choice: on a dreary school morning, the Stanhopes provided

an escape. The Chapel’s windows rise high above the paintings, meaning that the pictures were often out of sunlight, so that the gold of the angels’ wings and halos picked up only secondary light. Occasionally, though, the sun streamed through the windows and on to the paintings, creating a magnificent dazzle of colour that could be quite euphoric if it caught hold suddenly during a hymn, anthem, or sermon. In the evening, by contrast, the picture-lights above the paintings bathed them in a soft, warm aura.

It was not only the visual culture of Quattrocento Florence that Stanhope invoked in his pictures; it was also the atmosphere of Renaissance religious contemplation. This function of Stanhope’s painting was still relevant when I was a pupil, and I valued the pictures as visual focal points while reflecting on subjects of sermons or themes of services. Many of the schoolboys who first looked at these paintings in the nineteenth century were sons of clergy and attended two chapel services each day. While they were in all probability more religiously inclined than

many of today’s pupils, the two groups of Marlburians, then and now, share things in common. The meditative process that allows an adolescent to empty his or her mind for a short period of time and gain perspective on life will always be valued in a place as busy as Marlborough. In this, Stanhope was able to help. His colourful Florentine visions permit the mind to travel far beyond Marlborough’s enclosed environment, leaving behind the busy routine and the immediate concerns of the day. There is great assurance to be found in the rich colour, serene settings, and gentle faces of the angels. The paintings continue to hold to their purpose of being beautiful objects to contemplate whenever pupils find themselves in their presence. And, of course, angels represent the spiritual guidance that God provides, and in this the pictures reflect the care the College offers in preparing its pupils for adulthood.

Lily Martin-Jenkins

History of Art undergraduate, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 64

(IH 2014−19)

65

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision

Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, and the Scholars’ Window

Amongst all the notable artists and architects who contributed to the bel composto of Marlborough College Chapel a special place is reserved for William Morris (Aa 1848−1851). His most obvious contribution to the fabric of the Chapel is the Scholars’ Window that stands along the building’s south wall, commissioned to celebrate the College’s scholars. Created and executed by Morris’s firm, it has become so synonymous with the famous designer that it is often referred to informally within the College as the ‘Morris Window’.

College

Art and Vision 66

Marlborough

Chapel:

Marlborough

Vision 67

College Chapel: Art and

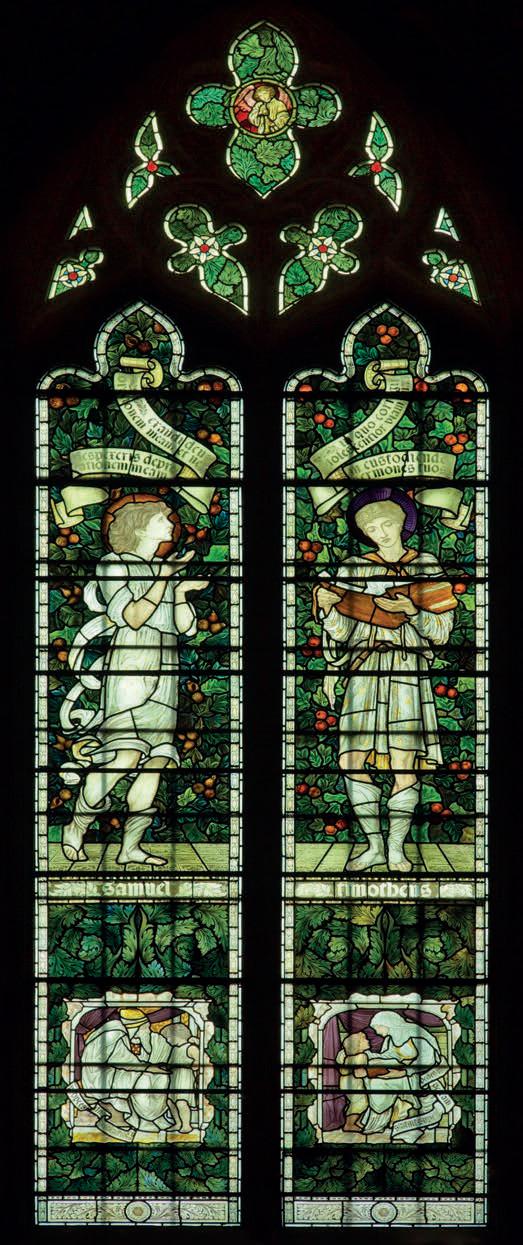

It was commissioned by the Master, Frederic Farrar, in 1875 and became one of Morris’s first projects carried out independently from Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., the company he had set up in 1861. This company had marked Morris’s first foray into manufacturing furniture, furnishings, and glass, and placed an emphasis upon the craftsmanship that Morris believed elevated workers’ skill above the soulless uniformity of mass production resulting from the Industrial Revolution. At a time when many within the Church of England were encouraging a revival of ecclesiastical decoration, and in the afterglow of Pugin’s medievalising aesthetic, Morris’s move towards the creation of stained glass was perhaps not a surprising avenue for him to explore. The commission for the College window stipulated that it was to be funded by ‘those who have gained scholarships from the College.’ In the event, this funding stream proved to be not as fast flowing as the College had hoped, forcing the Master to launch a general appeal, insisting ‘it is the only subscription of any kind for which [I] ever intend to ask.’

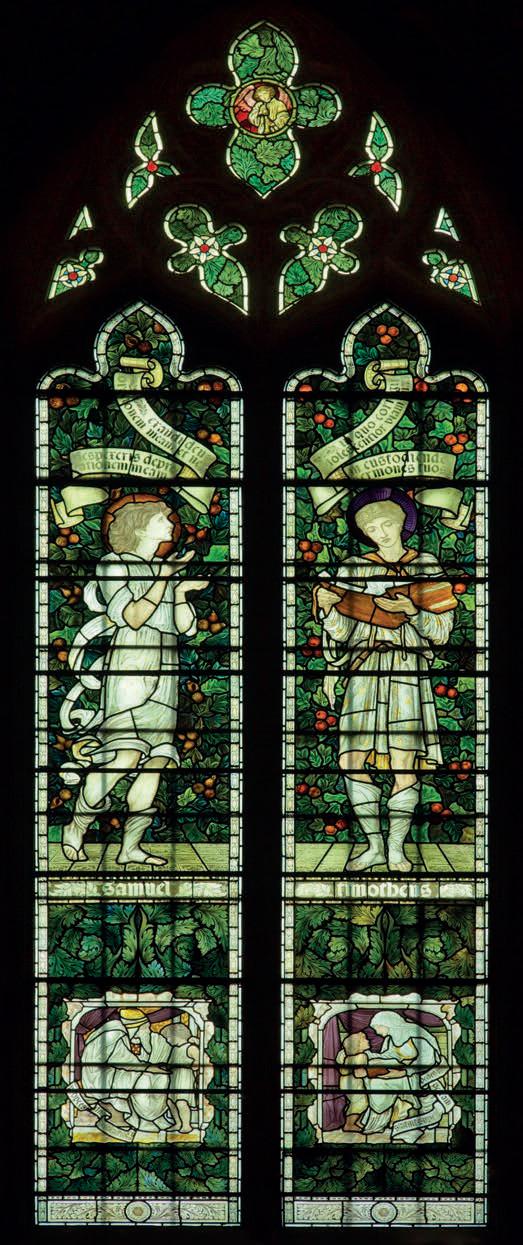

Despite its identity as the ‘Morris Window’, Morris’s role was essentially supervisory since the window was largely the work of other hands. Its design was wholly the responsibility of Edward Burne-Jones, and the manufacture of the window, involving staining, firing, and leading, was carried out by Morris’s skilled workforce. Burne-Jones had a personal stake in the project, since he had been

persuaded by Morris in 1874 to send his son Philip to the College, where he was enrolled in C3.

Interest in the window was immediate. Even before it was installed, it was the subject of a review in The Marlburian. Writing in September 1875, an anonymous editor was able to reveal that ‘The design is a very beautiful one’, but fretted how the window might fit into Blore’s Chapel, especially within its sap green walls: ‘The ground of the window is dark green. This is the only questionable part of the design, for, though on paper it looks very well, it may be doubted whether the greenish tone of the walls may not be too much for it.’ All such anxieties were to prove unfounded. Shortly after its unveiling, the window was reviewed in rapturous terms by William Spry Robinson in The Marlburian:

‘... it is almost needless to say that from every point of view it is a rare success. We never remember to have seen a more effective example of coloured glass work.’

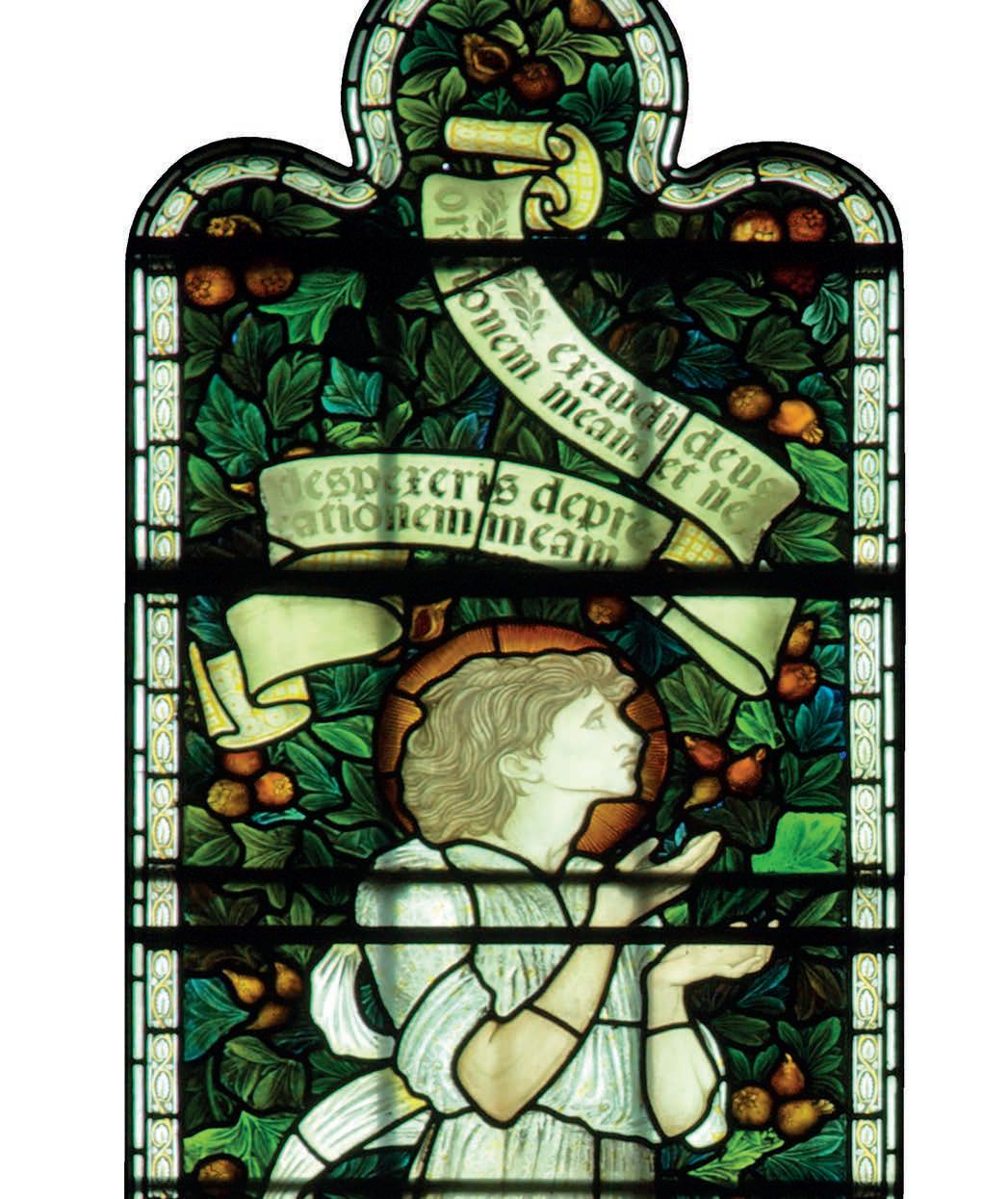

The subjects for the Scholars’ Window are two faithful boys from the Bible, one from the Old Testament, the other from the New, both ideal examples for Marlburians to emulate. The left side of the window features a full-length figure of Samuel,

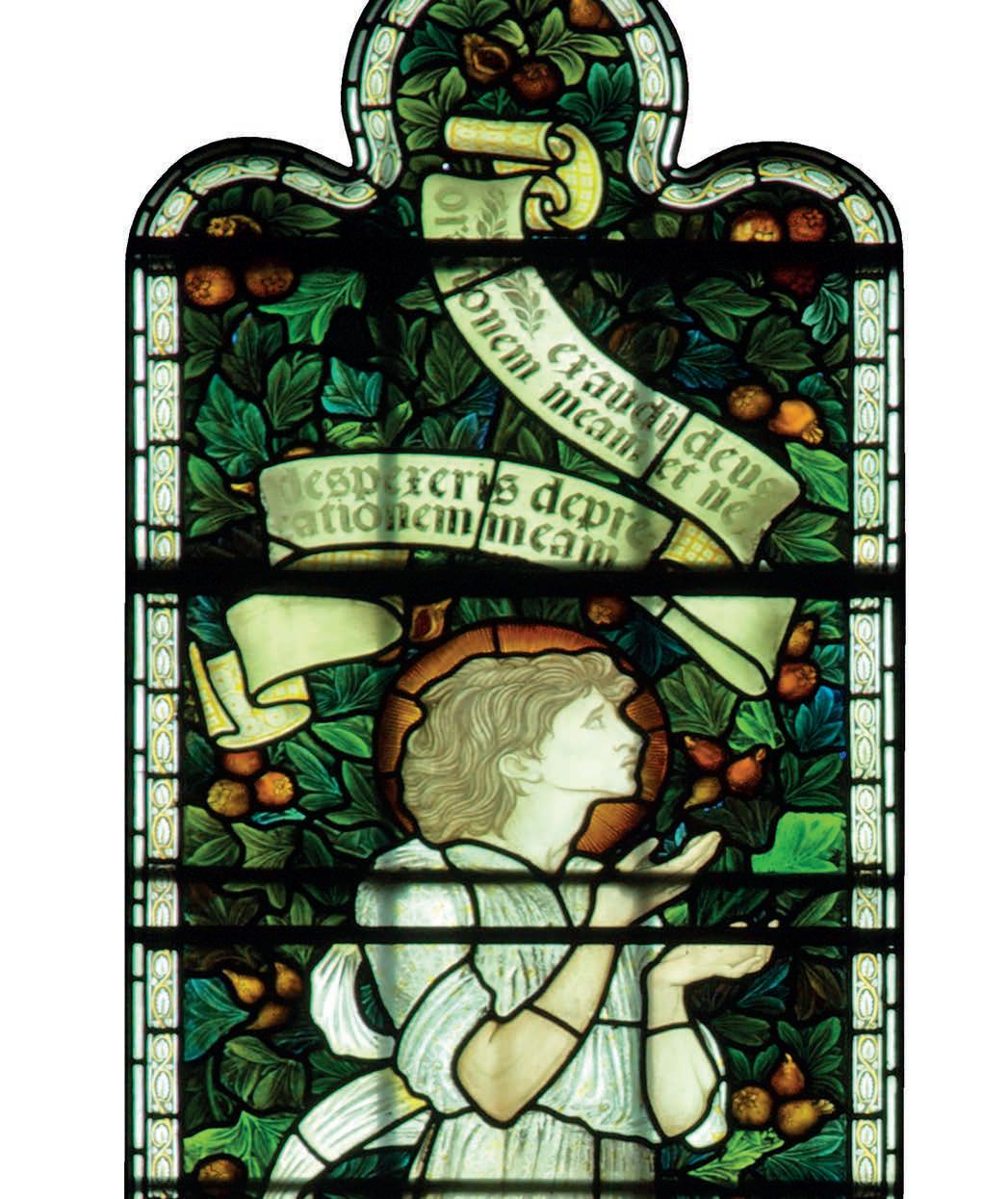

68

surrounded by a grove of pomegranate trees, set above a smaller scene of him receiving instruction from his tutor and mentor, the elderly priest Eli (see 1st Samuel 3). Samuel, who hears God’s call at night, is the type for those who faithfully accept God’s will. The Latin text in the upper part of the window comes from Psalm 54, 2: ‘Exaudi Deus orationem meam et ne despexeris deprecationem meam’ (‘Hear my prayer, O God, and do not despise my supplication’). The lower ribbon bears the text of Psalm 145, 18: ‘Prope est Dominus omnibus invocantibus eum’ (‘The Lord is nigh unto all them that call upon him’). The right side of the window treats the story of Timothy, youthful protegé of St Paul. The text above carries the words of Psalm 119, 9: ‘In quo adolescentior viam suam? In custodiendo sermones tuos’ (‘Wherewithal shall a young man cleanse his way? By taking heed thereto according to thy word’), and we duly see young Timothy studying a massive folio book in his hands. Below we see him again as a younger lad, standing at the knee of either his mother Eunice or his grandmother Lois, both of whom are commended by St Paul for their virtuous raising of the boy. The heavily laden boughs of the apple trees on this side of the window symbolise the fruitfulness that stems from Timothy’s godly upbringing. The accompanying text from Psalm 40, 2 reads, ‘Statuit super petram pedes meos’ (‘He set my feet upon a rock’). The window as a whole, therefore, commends dutiful obedience to God and our elders, and the pursuit of a path of service and studious devotion.

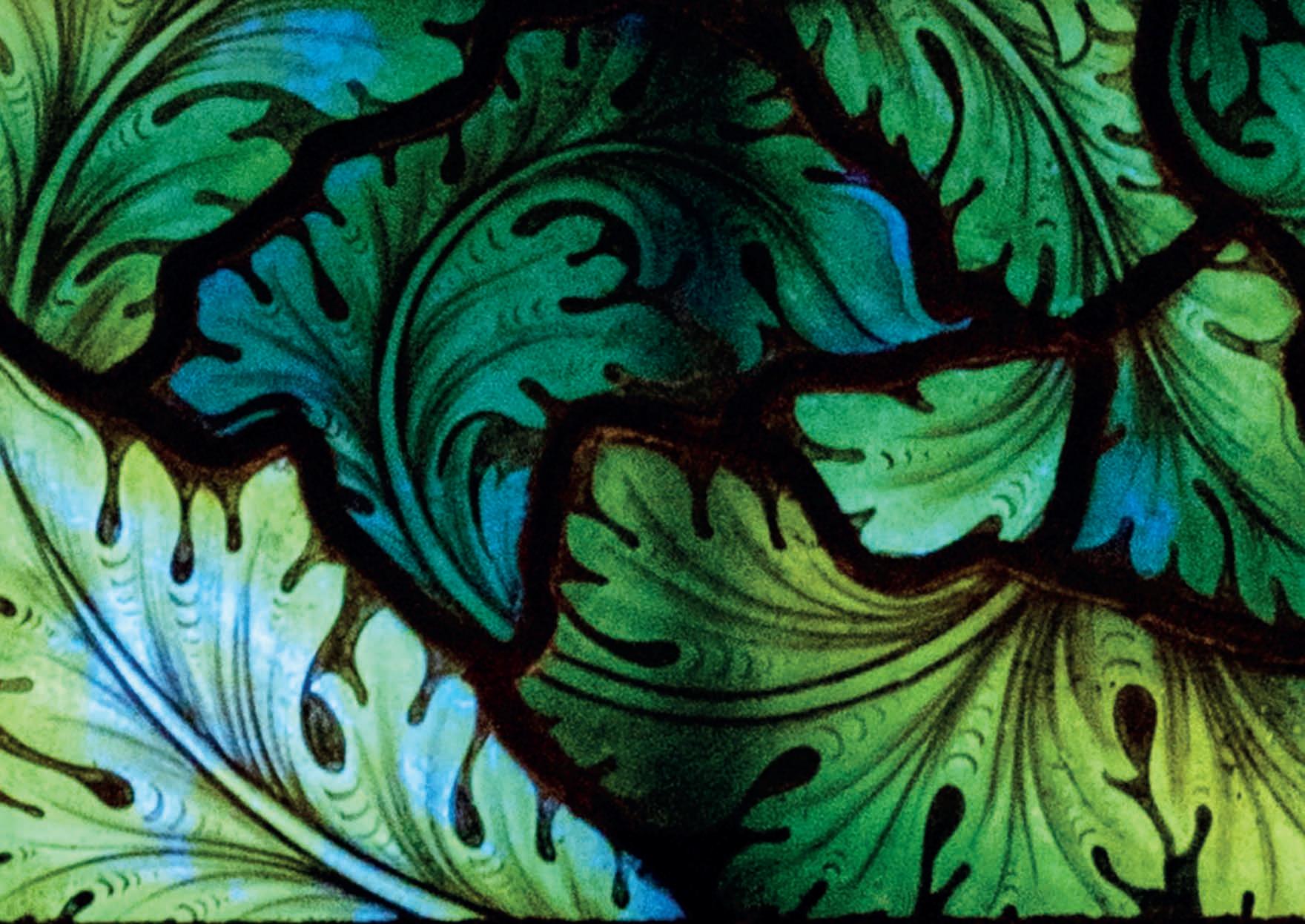

In this, the design is typical of Pre-Raphaelitism and the later Arts and Crafts movement alike. The organic imagery is highly decorative, blending fine art with craftsmanship in a way that foreshadows the aesthetic of Art Nouveau which was to emerge in the 1880s. Significantly, the Scholars’ Window evidences early examples of acanthus leaves in Morris’s work, a theme inspired by Ancient Greek architecture and which was to become one of Morris’s favourite motifs. But the larger influence remains medieval, an abiding passion for both Morris and Burne-Jones ever since their undergraduate days at Oxford. Thus, we find in the window intricacies in design and intensified colour, valued qualities typical of early stained glass, and therefore characteristic of Morris and Burne-Jones’s efforts in advancing the Medieval Revival.

History of Art undergraduate, University of Edinburgh

Delilah White (EL 2014−19)

Delilah White (EL 2014−19)

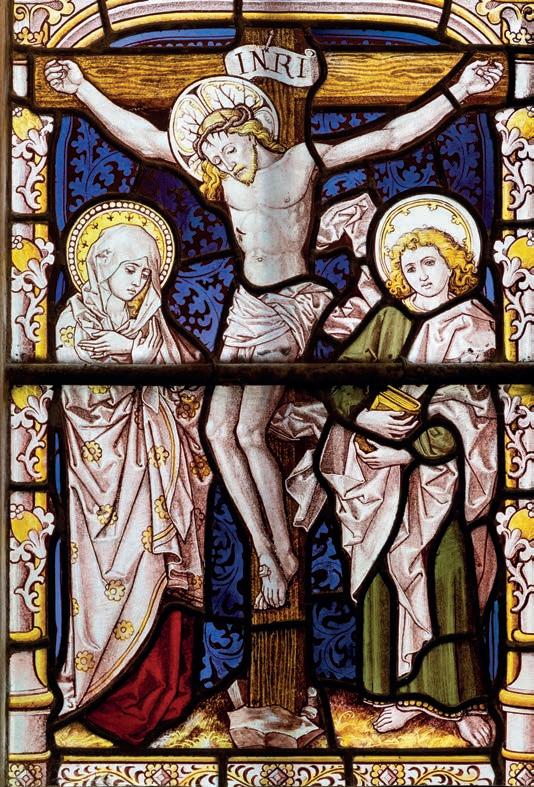

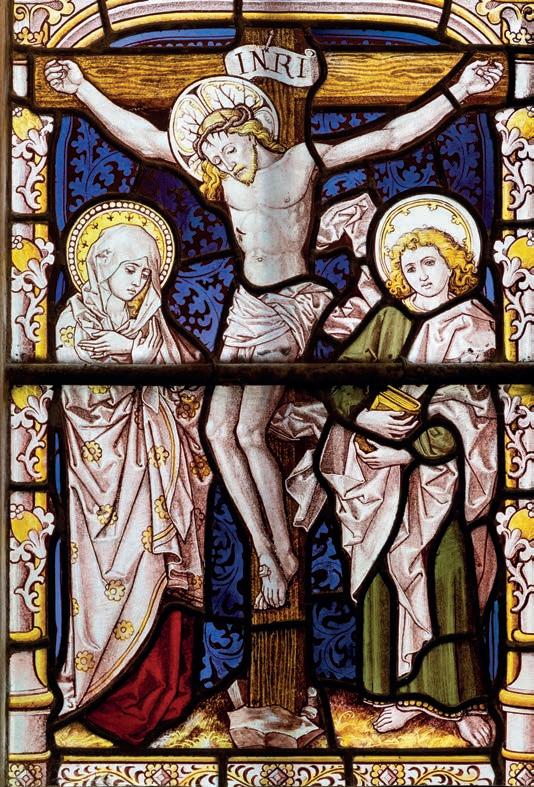

The Chancel Windows

The College Chapel makes a powerful visual impact on all who enter it, but also harbours areas less visible or visited. Its alcoves and corners hold subtler charms, including little-seen works which count among the most tender and poignant elements of the building.

Marlborough College Chapel: Art and Vision 70