intro

it would be an exaggeration to say 9/11 changed everything, but it altered north american and european values:

- it challenged the capitalist, liberal and western globalisation mindset which sees religion as a private belief

- it indicated that non-westerners see religion and politics as one

- it reinforced the view of many that religion is irrational and dangerous when left alone

- it challenged the endist western view that liberal capitalist society is the peak of human history

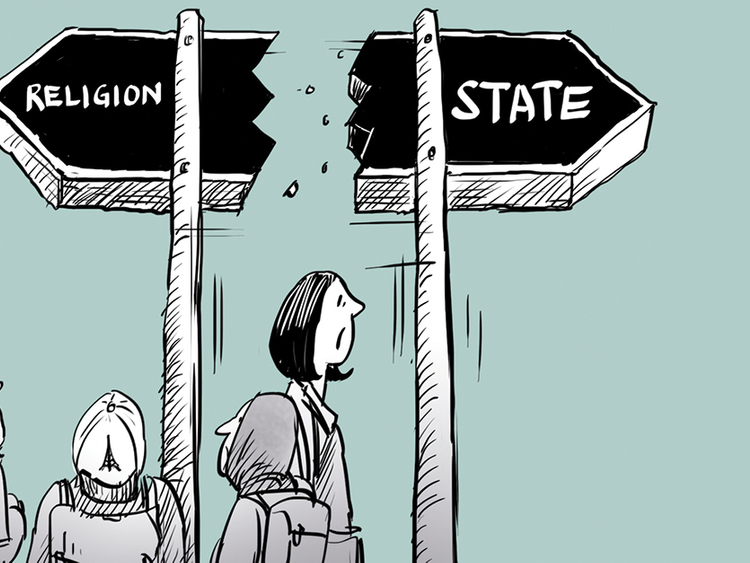

since 9/11 it has been hard to ignore religion’s role in world affairs, and the idea that religion should be separate has been challenged by the rise of fundamentalism. the effect in the west has been the reconsideration of whether religion should be excluded from all public life, or if we should properly understand religion as a fundamental part of human existence and can bring benefits to civilisation.

secularism

this is not an easy idea to pin down, but is broadly the belief that religion should play no role in the state, affairs of the government and public life. secularists don’t claim religion is right or wrong, but that in public matters it should remain private.

there are two forms:

- procedural secularism: the role of the state is to take into account all interests of all citizens. this means not giving preference or priority to religion but treating it equal to other institutions.

- programmatic secularism: the role of the state in a plural society is to be purely secular. all religious views should be excluded from public institutions.

there are different implications in each one, though. procedural is not discounting religion from the public sphere while programmatic is. this suggests there is more to secularism than balancing interests. in practice it is confusing and contradictory.

one problem is when procedural is actually programmatic, as shown by this obama quote:

democracy demands that the religiously motivated most translate their concerns into universal…values. their proposals must be subject to argument and reason, and should not be accorded any undue automatic respect.

president barack obama

this is problem. if religions are to translate their concerns to universal values, are they the same values? is obama’s view procedural or programmatic? which is preferable? former archbishop rowan williams favours procedural as this views the state as a ‘community of communities’. williams argues procedural has always been a christian idea, the role of the church is to proclaim the gospel, not govern. for williams secularism is a welcome challenge to the church, encouraging people not to privatise their religion but engage with all aspects of society and to challenge the dangerous implications of programmatic.

on the other hand there is france, which separates state and religion. it has been much debated because, for example, when does the state start being allowed to prohibit religious practices or clothing. this brings into question the problems of freedom of expression and human rights. the french government banned wearing of religious symbols in states schools in 2004.

secularisation

this is closely associated with programmatic, this is the active secularising of society by removing religion and ideologies from public institutions. it can also refer to the erosion of religion’s significance over time. there are broadly two reasons:

- sociological evidence: this has been used to justify the removal because religious is practised by fewer people it has ceased to have a place of privilege in society.

- religious harm: some have argued this is beneficial because of the harm religion causes, especially in opposition to human rights and civilised behaviour

the secularisation thesis is a controversial term describing the process. the traditional meaning is the growing number of people who have no religious affiliation, or where religion loses influence on society. the thesis is that over the last hundred years church attendance has declined and people are rejecting religion in favour of non-religious ways of life. in western europe this is also known as de-churching, being a mainly christian decline.

it is highly controversial because it is hard to define:

- measuring and defining terms: it is not clear how th process is measured or defined. in the us over the last 100 year the number of people with a religious preference has halved, but many continued to pray or believe in god. this shows that although there is less commitment, there is still beliefs.

- influence and authority: another debate is how much influence religion has on society. how much influence does the anglican church have on british social policy, or the catholic in italy? some argue that while the traditional influences decline, they are replaced with new religious movements which rapidly gain social acceptance. is it actually just that mainstream religions are declining, not that secularism is rising?

- religious commitment and evidence of the past: those who support the secularisation thesis argue that in the past people were more committed than today, so it is more secular. others argue that it was just socially expected, not more committed. today people attend church because they want to.

as contentious as the issue is, it is true that influence is wavering. secularism poses a challenge to traditional christianity, but does it mean that it will die out? even in the usa some argue it is declining, albeit slower than in europe.

reactions to the thesis are often forceful. in traditional societies, it is seen as an invention of liberals to justify diminishing of influence of the church in the state. on the other hand, it is embraced by those opposed to religion.

god as illusion, wish fulfilment and a source of harm

programmatic is developed from the late 18th century. european intellectuals developed powerful arguments for the abolition of religion. auguste comte held the view that civilised society develops from the theological to the metaphysical to the positive (scientific). he believed religion would give way to secular positivism and society would be rid of false world views.

this view supports liberalism’s idea that we live happier lives without the superstition of religion. moreover, religion is regarded as harmful and even dangerous for individuals and civilised society.

two scientists have followed comte, freud and dawkins. both argue that scientific method is the only way to determine truth form falsehood and furthermore that religion is indicative of less civilised society. both have argued for the secularisation of society on the grounds that christianity is infantile, repressive and a major cause of mental and physical conflict.

sigmund freud

he considered more developed forms of society as major causes of oppression. he believed neuroses were the result of a natural human instincts being repressed by tradition and conformity, and that religion was a primary cause of psychological illness.

although freud was a jew, he did not practise his religion nor believe in god. he was, however, fascinated by religion and wrote a lot about them. his central claim was that religion was an infantile part of human social development when it is still in need of external support and comfort. david hume had already come to this conclusion, saying it was mainly practised by the uneducated, but those who are mentally grown up do not need it.

the ignorant multitude must first entertain some grovelling and familiar notion of superior powers.

david hume

hume had no evidence, but freud used psychoanalysis to show religion as a sickness which can badly infect individuals and societies.

as a scientist, freud argues that only by using reason and questioning the superstitious beliefs can human societies live happy lives. to every objection that his imaginary opponent raises in his essay, the future of an illusion, freud responds that future reason will prevail, religion will end and humans will be content.

religion as wish fulfilment

this comes from a short article written in 1928. a year before an american doctor had written to freud about how aa student he had seen a dead ‘sweet-faced dear old woman’ in a dissecting room, causing him to lose his faith and discover it shortly after through a powerful conversion experience. the doctor wanted to persuade freud to rethink his atheism.

freud replied two-fold. first, god had not shown himself to freud, nor answered any of his prayers, so he had no good reason to believe. second, freud’s analysis of the man’s experience showed a rational explanation for the doctor’s experience, as a classic example of an oedipus complex.

freud questioned why this old woman was different form the rest of the cadavers, and his answer was that the woman must have reminded him of his mother. the experience roused in him a longing for his mother, from the oedipus complex, followed by a feeling on indignation against his father. the infantile anger manifested as anger against god, the voices he had heard were s ‘hallucinatory psychosis’ warning him to obey his father like a child. the guilt he had felt for wanting to rebel against his father as a child, which had been repressed, was momentarily revealed in his adult life. the following conversion was a wish fulfilment to restore his childhood sense of security and can be explained in psychoanalytical rational terms.

religion as infantile illusion

in the future of an illusion, freud argues that religion has been the most powerful means of overcoming human fears of death and suffering caused by humans. he is interested in the way in which religion has continued to provide comfort and meaning against the experience of the ‘terror of nature’, helplessness in the face of death and sufferings in society.

according to freud, religion provides comfort through its rituals and worship. just as little children find comfort in discipline and order in their lives from their parents, the rituals such as washing hands continue the process through the ‘suppression, the renunciation of certain instinctual impulses’. this is most noticeable in the repetition of ceremonies of worship and prayer, which accept the worshipper’s guilt and ask for forgiveness. repetition like this is obsessional because it keeps the ego from being controlled by sexual urges.

so freud concludes that it is a ‘universal obsessional neurosis’. the repression of basic urges is replaced by promises of afterlife and rewards or punishments. but these are illusory and a device to ward off fear, compensating for pleasures forfeited.

so freud’s conclusion is that although religion may do some good, in order for society to grow and develop rationally, religion needs to be abolished. just as a neurotic patient must be treated for his irrational fears, so must society rid itself of religion for people to be free and happy. freud is optimistic that this will happen, ending his essay with the claim that the illusion is to think that religion is the source of true happiness.

critique of freud

freud was a reductionist, but as keith ward remarks, reductionism is hardly an adequate explanation for the vast amount of religious and spiritual experiences. mystical experiences are to be found in every religious tradition, characterised by the merging of self and a sense of the ‘other’ and imparting of deep spiritual knowledge. in fact freud is not nearly as much a scientific reductionist as he thinks. despite his suspicion of religion which stops human development, there is evidence to suggest he wasn’t wholly critical of it. a friend wrote to him about such an experience, which he called an oceanic experience:

i would have nevertheless liked to see you analyse the spontaneous religious feeling…which is…the simple and direct fact of the feeling of the eternal.

romain holland

freud does not reject the validity of this experience even though he himself had not felt it. despite his deep skepticism of religion he answers:

from my own experience i could not convince myself of the primary nature of such a feeling. but this gives me no right to deny that it does in fact occur in other people. the only question is whether it is being correctly interpreted…

freud

other responses are as follows:

- truth claims: he may be right that some aspects of religion are neurotic and obsessive, there are states of the mind and they do not in themselves disprove religious truth claims.

- religion is enabling: he argues religion is an obsessional and infantile illusion which cut a person off from the real world. this may be true for some but for others it is enabling, giving deeper appreciation for life and helps to form communities with shared values and a sense of purpose.

- guilt: freud is right to illustrate how religion cause be a cause and perpetuation of guilt and we should be wary to warn against deeply controlling religious traditions, but not all religion is controlling. many religious traditions provide a source of meaning and fulfilment which is lacking in a material existence.

- wish fulfilment: although some wish fulfilment is a source of illusion, it can also be a source of creativeness and fuel the imagination.

richard dawkins

as a scientist and champion for secularism, dawkins argues that religion is given a disproportionate place in society and appears immune to criticism because there is still a respect for it even when it is dangerous and intolerant.

overall dawkins argues that the supernaturalist and monotheistic religions are particularly a cause of mental and physical harm. this is not only because a belief in god is unfounded but also because a creator god justifies irrational and dehumanising behaviour. as a programmatic secularist, his aim is to persuade all right-thinking people that god is a delusion and that atheistic secularism is the only plausible alternative.

although his arguments are in many of his books, they are most clear in the god delusion. the book’s aim is ‘intended to raise consciousness…to the fact that to be an atheist is a realistic aspiration, and a brave and splendid on’. specifically it urges us to imagine a world without religion, accept that the god hypothesis is weak, realising that religion is a form of child abuse, and accept atheism with pride.

science and reason, religion and delusion

dawkins began his attack on monotheism by questioning why anyone would want to believe in a something for which there is no evidence. for dawkins, the best explanation for the processes of nature is in evolution. it does not need a god hypothesis to make sense and doesn’t need a god to lead it to perfection since it has no grand aim. unlike god, evolution is supported by a large and accepted body of evidence. such a weight of evidence, he argues, means it makes more sense that minds, beauty and morality emerge without a need for god. so he says a belief in god is unnecessary and deluded.

delusion is the persistent false belief contrary to the vast body of evidence which leans in favour of evolution. it is intellectually naive to try and reconcile the spiritual and material by saying they are different categories. for example stephen jay gould’s NOMA (non-overlapping magisteria) which says the supernatural is a totally different kind from the material world and its not subject to scientific rational enquiry.

dawkins rejects this. he argues all things must be subject to rational enquiry otherwise one could believe anything, like in a cosmic teapot. when reason is applied to religion, all that rational arguments for god’ existence can do is demonstrate at very best that it is inconclusive. dawkins says the advancement of science makes the god hypothesis more and more implausible, and the rational position is atheism.

religion as indoctrination and abuse

if the debate were merely about god’s existence then dawkins might have concluded that there are many sad and deluded but harmless people in the world who are free to believe what they want. but he argues they are not harmless because they cause conflict and worse, when taught to children, become a form of child abuse.

religion is abuse because so many of its deluded beliefs damage children and adults psychologically. he gives a wide range of examples, including hell houses in the US where children are taught about the terrors of hell and how to avoid it. he is critical of how religions initiate children and label them before they have an opportunity to understand what that means.

even without physical abduction, isn’ it always a form of child abuse to label children a possessors of beliefs that they are too young to have thought about?

dawkins, the god delusion

some of his examples are hard to reconcile with the moral principles promoted by religion. again and again christian notions of love and compassion are contradicted by religious leaders practising the opposite.

a recent example which can illustrate dawkins’ point is a film of the real story of philomena lee, a teenager who became pregnant and was sent to a convent home for single mothers by her catholic parents. in exchange for food and lodgings, her child was taken from her and sold by the nuns while the child was told his mother died in childbirth. later as an adult she enquired, and the nuns lied about burning files, saying they were lost.

finally dawkins reserves some of his most outspoken criticisms for schools which reject teaching evolution in favour of creationism. it is a scandal to teach children the world is 6000 years old because the bible says so, while the mountain of evidence points to it being at least 14 billion.

critique of dawkins

reactions to dawkins’ secular atheism have been extreme from those he attacks most, i.e. conservative fundamentalist christians. but is it reasonable to reject all christian beliefs just because of a few extreme believers mainly in the US? dawkins’ response is that these views may seem extreme to us but they are not in the US and other non-european countries.

dawkins’ challenges are persuasive but many consider his arguments overall not convincing. alister mcgrath puts forward the following points:

- reason and faith: many christians disagree with dakwins and say that faith is rational. reason is necessary to test true and false beliefs before faith makes the ultimate leap to the transcendental. however rational we are there are always things that we believe that we cannot prove beyond doubt.

- complexity: dawkins is right to criticise the ‘god of gaps’ argument, the view that the universe is so complex and cannot be explained by science to the answer is that it was cerated by god. but the alternative isn’t necessarily atheism. the fa t that the universe is intelligible may point to god, too. there is no science/religion conflict.

- metaphysics: dawkins argues, as a positivist, that answers to the big metaphysical questions are meaningless because they are outside scientific investigation. many scientists reject this view and consider that science, theology and philosophy all prove useful insights into these questions.

- science and religion’s complementary relationship: dawkins’ biased analysis of the NOMA forgets that many scientists and theologians argue that there is a complementary relationship between science and religion as they reflect different aspects of human life the material and spiritual.

- violence as a necessary condition of religion: although dawkins gives many examples of the harm done, it is not a condition of religion – jesus taught against violence. the same charge can be posed to atheism, such as the harm of communism, but dawkins doesn’t accept that.

objections to the secularisation thesis

charles taylor

taylor questions why we find it easy to not believe in god in the western world, despite it being the norm through history. he claims the answer is what he calls ‘subtraction stories’. these are stories we now use to demonstrate the truth of secularisation by removing religion as thoguh it were obvious.

he says we have outgrown religion and the stories or explanations we now use to explain the world are designed to show we can live full lives without the need for god or a higher power. these subtraction stories, as made by dawkins, freud and comte, lead to what taylor calles self-sufficing humanism, but it is deeply unsatisfying.

- first taylor argued that a failure of secular humanism is that it gives too much importance to the individual and private experience, but it breaks the communal aspects of society.

- second it is not that we have suddenly discovered that doesn’t exist, but that the western world is out of line from the dominant historial world narrative. god has been present and essential through history.

taylor’s argument is that until we steer ourselves out of this secular phase of history, we won’t experience the fullness of life which means having a divine.

terry eagleton

eagleton’s suspicion of secularism derives from his marxist and christian beliefs. although marxism is traditionally atheist, eagleton considers it wrong of marx to discount religion and what it contributes to life. his use of marxism makes him suspicious of secular capitalism and its impact on culture.

first, although it is true that religion has been harmful, this must be balanced against the wealth of art, architecture, literature and more that has come from a religious imagination. scientists think these occur without religion, but only religion can capture the highest aspect of human experience. he argues secularism is largely doomed, because it cannot replace what religion has.

religion is an exceedingly hard act to follow. it has, in fact, proved to be far the most tenacious, enduring and widespread symbolic system humanity has ever known.

terry eagleton

the significance of religion is that it touches on deep truths about existence which people have been prepared to die for. no one is prepares to die for music or sport, the secular religion replacement, because they are not important enough for make the sacrifices religion demands.

second, eagleton’s view is that the root cause of secularism is the way western secular capitalism have value free competition by privatising everything. this has a knock-on effect where morality and religion are also considered irrelevant and private form the public sphere.

finally, eagleton argues that 9/11 indicates that the positivist dream of a world without religion is not only wrong but without proper understanding can appear in a highly toxic form of extremist fundamentalism. eagleton is not condoning violence, but his analysis is that fundamentalism comes from ‘anxiety rather than hatred’, anxiety caused but the perception of the anti-religious western message through the world.

9/11 shows two extremes of anxiety: faithless western secular atheism and its fear of religion, and faithful religious fundamentalism and its fear of positivist and capitalism secularisation. both, he argues, are equally flawed.

christianity and public life

the answer to whether christianity should continue to be a main contributor to society’s values will depend on whether you consider it to have insights of if it should be replaced by secular humanist values.

secular humanism

this is a board term, describing all those who believe humans can live good lives according to reason without religion. freud and dawkins are secular humanists. beyond the basics there are variations, especially between programmatic and procedural.

the amsterdam declaration sets out the main aims of modern humanism:

- humanism is ethical: humans all have worth, dignity, and autonomy

- rational: science should be used creatively as a basis for solving human problems

- supports democracy and human rights: democracy and humans right are the best way for humans to develop with potential

- insists that personal liberty must be combined with social responsibility: the free person is responsible to society and the natural world

- is a response to the widespread demand for an alternative to dogmatic religion: reliable knowledge of the world and us arises through a continuing process of observation, valuation and revision

- values artistic creativity and imagination: the arts transform and enhance human existence

- is a life-stance aiming at the maximum possible fulfilment: the challenges of the present can be achieved through creative and ethical living

humanists are clear that ethical and spiritual values are not derived from a higher power but express human values and aspirations.

education and schools

dawkins is an outspoken critic of the provision of faith schools in a secular society. some argue that having many types of faith schools contributes positively to social diversity and cohesion. dawkins says this is outmoded and confused. ‘diversity may be a virtue, but this is diversity gone mad’.

arguments against faith schools:

- they create isolated communities and fail to integrate pupils into the wider secular society

- many fail to teach proper science, especially fundamentalist and conservative beliefs

- they leave pupils open to radicalisation

- the state has no responsibility to teach faith, it is a private matter for local faith communities

- religious studies should be part of curriculum as long as it includes all major world religions and non-religious belief systems. children should be taught diverse faith claims and that some religious truth claims are equally non-religious

arguments for faith schools:

- there are no value-neutral schools, faith schools just operate according to religious values which reflect the diversity of british culture

- they offer a distinctive education based on moral and spiritual values. they enhance, not detach from wider curriculum

- they aid social cohesion because they support and value local faith communities

- they are popular with parents

- many faith schools do not make faith a requirement for entry, but are able to better foster any belief because they have a better understanding than secular schools

government and state

since the 18th century the generally accepted view is that church and state should be separate. the secular assumption is that faith is a private matter and should not interfere with the state dictated by law and reason.

the creation of the USA in 1776 is an example of how the creators of the constitution, founded on life, liberty and a pursuit of happiness, came to separate church and state. part of it allowed freedom of religion but prohibited congress from establishing a state religion. at the time the reasons were to avoid conflicting political claims between church denominations, but with the influx of immigrants of different religions, there is even greater reason to separate the two. however this has not been detrimental to religous practice, but the freedom to practice it has made the USA a highly religiously observant country.

the alternative to separation is a theocracy, the belief that religion should pay a part in public life and government. programmatic secularists consider theocracies to be undemocratic.

- dominionists argue that america should be governed according to biblical laws, are mostly protestant, evangelical and conservative. dominionist theology is based in genesis where god commands men to have dominion over the earth and they believe god’s command also applies to stewardship matters of the state and the world.

- reconstructionists are calvinists who believe in the dominionist notion of society but also justify theocracy by pointing to the law in the OT where israel’s life was ordered and governed according to the law god gave to moses.

in britain the situation is different to the majority of europe, as the queen is the ‘supreme governor’ of the anglican church. twenty-six bishops automatically sit in the house of lords and at significant state events which the church presides. citizens, regardless of faith, may use their parish church for baptisms, marriages and funerals. while some agree this is outdated, others consider this to be the way in which the state provides a spiritual service, like the NHS provides healthcare.

britain is not a theocracy but some programmatic secularists argues that the last traces of its theocratic past should be abolished for a full democracy.

but the view of many christians is that programmatic is anti-democratic because it actively removes the historic place of christianity from all public institutions. procedural, however, is not, because it offers the church the chance to be fully engaged with society and contribute to the success of secularism but offering the widest range of opportunities for all citizens. rowan williams argues the church has a key role to play in resisting anti-democratic movements and also fundamentalist sects that see secularism as a threat.

the challenge of secularism is therefore not necessarily a threat to christianity, and it is right that it should give a reasonable account of itself and justify its place in society where there are many different belief systems, which in a democracy seek to live harmoniously.