We made our own parchment – during a unit on limp parchment bindings in my Historical Book Structures course at the UI Center for the Book [Spring 2018]. For an overview of the process, see my previous post on parchment making. Bill Voss [UI Book Conservation Lab] and I had collaborated on this a couple times before, learning the parchmenter’s craft through a bit of reading, advice, and fresh skins from premier parchmenter, Jesse Meyer. Through repeated trial and error the process is getting faster and more streamlined. We made a couple of stretching frames and pegs in our previous attempts, which are clumsy to keep tight and to string up – so this time around Bill suggested tying up the wet goat skins while it was laying flat on the table, then stringing it up on the frame with ties already in place [rather than trying to do this directly on the stretching frame]. This worked well and saved a lot of time.

I wanted to have time during a class period for students to experience the full parchmenter’s practice [starting with a de-fleshed, de-haired, wet skin]. So I had one wet skin ready to be strung up and stretched, and one dry skin [already stretched] ready to be scraped and sanded. It was February in Iowa, so wet work was done indoors [above] where it was warm, to allow for longer working and drying time [usually dry within a few hours under normal temperature and humidity]. Dry scraping and sanding of the stretched skin was done out of doors [below], since it is a faster process [to get a suitable sheet for parchment covers] and is quite dusty. We used Bill’s lunarium, and a palm sander with various grits of sand paper from rough to fine.

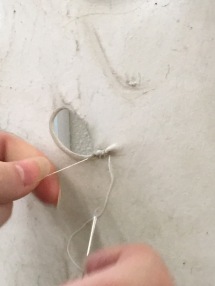

During the wet work, a couple of students were interested in parchment repairs, so they sewed up a hole in the wet skin. Holes are repaired to keep them from getting bigger when the skin is stretched. Holes were often not sewn closed, leaving telltale circular openings in the final parchment sheet. These were sometimes used creatively, the shape incorporated into figurative penwork or embroidered for decorative effect. Taking the parchment from wet skin to final dry sheet is a great experience, since it provides a deeper understanding of historical parchment production and use and gives insight into the range of parchment qualities one sees in medieval and early modern books. For example, the image below shows a evidence of parchmenter’s repair on the cover of a limp parchment binding from Tuscany, Italy, 1471 [Newberry Library, VAULT Case 152].

Here the user didn’t shy away from using the part of the sheet with a sewn repair or a less than perfect sheet. This is often the case with the parchment used for limp and semi-limp covers, and suggests that medieval and early modern parchmenters were selling a range of sheet materials, graded by thickness, color, surface quality, level of defect or irregularity. The parchment used for the outside of a binding was durable and thicker than what you would find on the folios of a fine book of hours for example – and the bookbinders were looking for something durable and generally did not need a blemish-free product. Medieval and early modern parchmenters understood their product, and scribes and bookbinders did too. Parchment was the standard sheet material [for interior quires] in Europe until the late 15th c., when it began to compete with paper. Though papermaking had been made in Europe for centuries, production really ramped up by the early 1500s in an effort to keep up with the demands of early printers. Parchment did not disappear in the 16th century. It continued to be used for high end manuscripts, liturgical books, specialized administrative documents – and increasingly for the covers of books in the form of limp, semi-limp and stiff parchment bindings.

So, the parchmenter’s process is straightforward, but labor intensive, and requires skill to make a fine product. Basically, the wet skin is strung up on a frame, scraped, tightened, scraped, tightened [repeat], until sufficiently stretched, then dried, scraped or sanded – creating was Chris Clarkson called a ‘high tension sheet material.’ When both our sheets were dry, I cut them down from the frame, then cut the skin into widths to distribute to students to put on their own limp parchment bindings [look for future post on these]. I will be teaching a historical methodology course with Dr. Heather Wacha at the Newberry Library in April 2019, on codicology and medieval and early modern book history. We’ll be making parchment, looking at a bunch of old books, and learning how they were produced 500 years ago. Check it out!