UPDATED (2014-11): now with added gentlemen’s tailoring, a toorie, old ladies, a sexy Spanish lady academic (updated later—2016-06—with more sexy PhD costumes of yore and some more about what PhDs are), and butter.

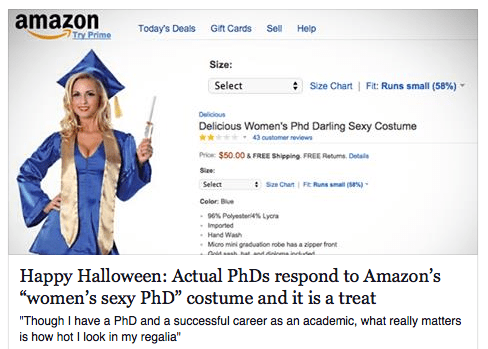

Or, some comments on this news item today, via Salon (2014-10-31):

Looking for a last-minute Hallowe’en costume? Thinking about dressing up as an academic? Are you an academic and thinking about how you “dress up” as an academic every day?

It has been some considerable time since I wrote anything on stereotypically girly stuff; this can be of a more amusing sort, does not necessarily have to be post-feminist or anti-feminist, can indeed be feminist, and may have something to do with the medieval, medievalist, or medievalisings. The last such mentions on here would have been via Trotula of Salerno , the Quest for the Holy Grail, and Lipstick Queen’s “Medieval.”

Here’s the deal.

Like many people who do some sort of work, I don’t have vasty swathes of time to get ready in the morning. Like other people whose work involves dealing with other human beings, I have some obligations to look vaguely human and presentable. Emphasizing the vagueness here, as anyone who’s seen me around knows that I’m not the most chic soignée creature around. But looking (and smelling) socially acceptable is an obligation, when interacting with other people. Not being offensive, intrusive, objectionable. Not causing others distress or physical pain.

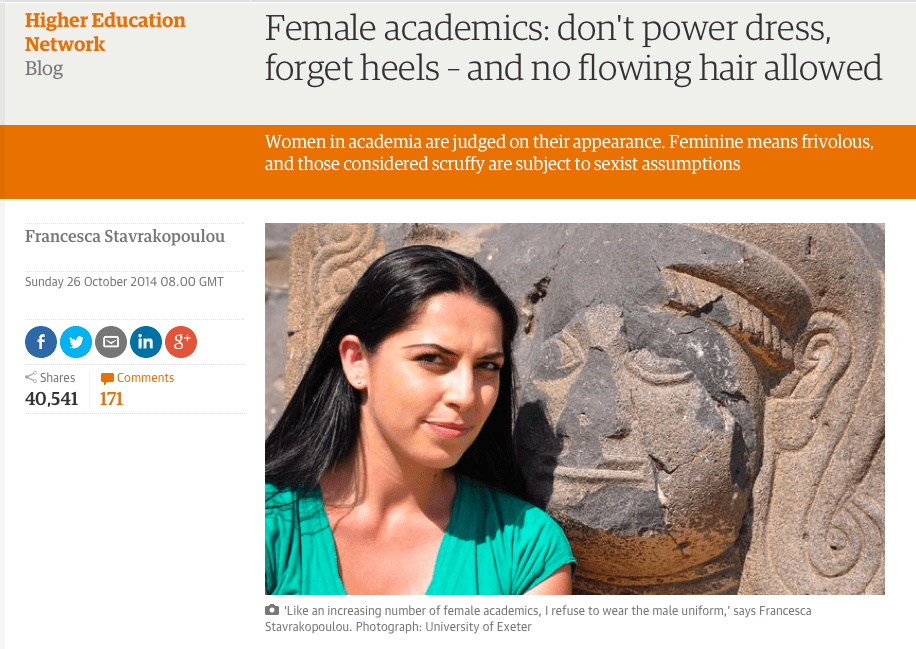

Like others working in academia, there are stereotypes and expectations to deal with. One ought to look what I’m going to call “appropriately professional,” and “professionally appropriate,” that is, in a way that is in keeping with the work one does. What exactly that translates to in terms of clothing is something that has been discussed in the news recently:

The Guardian, 2014-10-26:

and it’s also been a topic of conversation at (at least) a couple of sessions of UBC’s TA Training Community of Practice. What should faculty wear when teaching? And what should graduate student teaching assistants wear? How “mini-prof” should they be, and what variety thereof? TAs are in a tricky situation: they are themselves students, yet are teaching other students; how “professional” should they look?

There is the ENArque version of just going full throttle for business drag.

Now, I should admit at this juncture that I loathe suits. Because they are the uniform of The Suit. I never liked Suits and the kinds of pseudo-work in pseudo-occupations they represented; I’ve grown to like them even less in recent years. In academia, The Suits somehow changed from being useful college servants and university support, to running the place. Outide academia and more generally, The Suits are in process of ruining the world through their financial and environmental activities.

The attributes associated with The Suit over its rise in the last two centuries? Questionable. For many people, no longer positive. And passé. Nineteenth-century imperialist values, macho conquest and growth, the Viagra Paradigm. As with universities now, this was a historical case of support staff rising above their station; at that time, in relation to the military, and a step (like the French Revolution) in the longer dance of class conflict.

And that’s just Suits in their day-job (or excuse for one). Suits on the loose of an evening turn louche: City bankers bigging it up in bars, throwing the bonuses around, misogynist homophobic racist thugs behaving badly, and doing so to what in North America would translate as frat-boy excess. Think of what Robin Thicke and his image are supposed to suggest. Suits represent money and profligacy. Again, these behaviours and values are passé: twentieth-century values from the made-up world of that century’s doctrines of economic progress, and the made-up pseudo-field of high finance. Or, as its longer past history and ancestors would put it, “gambling.”

It would be more charitable to add the label “creative”, and more realistic to add “sociopathic, psychotic, monstrously egotistical, destructive, and villainous.” Maybe even “evil.” As The Suits have divorced what originated as their distant ancestors’ courtly and courtierly business from courtly values and virtues, suit-wearing no longer suggests gentleness or gentility, or confers such qualities on the bearer: quite the opposite. The “gent[leman]” inside the suit is no longer Medievally gent; nor bon, cortes, fin, preu, leal, noble, de prez e valor. The associations of power and authority are still there; assumed and self-aggrandising trappings, though. Suits continue to be worn by Suits and would-be proto-Suits, in the hope of acquiring what are perceived to be positive suitish qualities by some sort of magical diffusion.

In their wanton ignorance and folly, the besuited may believe that in suiting themsevs, they themselves also thereby acquire all positive qualities ever associated with suits, including courtesy and gentlemanliness. Such confusions of the different senses of “value” and “worth” are nothing new; see Troubadour lyric poetry for further details. The more expensive the suit, the more convincing it is; money is a magical fairy-dust with which to blind others. It’s not about “being professional” (or whatever you are), doing so via your bons faicts et dicts; it’s about playing a part, looking the part, branding, marketing: the applied rhetoric of seduction, translated to a flirtation emptied of all hope. These are the sterile hollow evil Suits of Michael Ende’s Momo: a book that had a formative influence on my attitude towards Suits, partly through childhood nightmares. So. Do not be misled by fine tailoring, nor let expensive suave appearances finesse you into accepting their glamorous illusions for deeper truth. Remember Jerome, Jean de Meun, Rabelais: “la robe ne fet pas le moine.”

It is 2014 and a different world from those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One in which a Suit has lost all aura of respectability. Because, here and now, Suits are not respectable.

For a good guide on what counts as respectable, socially useful, productive, individually satisfying work: I would suggest consulting the Old Lady Job Justification Hearings, recurring sketches in That Mitchell And Webb Sound. A sample:

Then there is the maxim: “dress for the job you want, not for the job you have.”

This last one leads us to the classic professorial garb, in the style of M.R. James, Indiana Jones, and many a twentieth-century stereotype, caricature, and grotesque:

The very practical three-piece tweed suit, preferably with an assortment of tweed ties, remains a classic. Good heavyweight tweed will last decades, possible an entire career, so is a good investment if you reckon you’ll be in a tweedy profession for life. The tweedy approach to academic dress featured in the Jonathan Wolff piece in the Guardian of 2014-10-21, to which Francesca Stavrakopoulou was responding in her piece (mentioned above) of the 26th.

In this day and age, serious Investment Tweed might risk looking arrogant: suggesting an assumption that you’ll be in a specific career (let alone one single job) for life. On the other hand, it’s good recession-proof dressing. Buy once, then simply buy a few shirts etc. every year (eventually, t-shirts worn under the waistcoat and no jacket for a light, lighter-hearted Summer Look). For life. That makes it a Wise Investment, as well as a sound anti-consumerist non-wasteful environmentally-friendly one. And proper Scottish tweed supports and sustains smaller-scale local environments and economies, from land and sheep to humans.

Tweed ages well. It develops patina. You can add elbow-patches. There’s little that’s more academic-looking than elbow-patches. Tweed is already pretty weatherproof to start with, and when worn frequently in the rain, good heavy thick tweed will felt. Medievalistically-speaking, it’s halfway to armour.

Bonus: all stains, dribbled food, marks from chalk and pens, etc. will be invisible, blending in with the general pattern. Add a patterned tie or scarf and you’re sorted: might be the female equivalent of a beard. Other related options to tweed: boiled wool, felted wool, anything made from Icelandic wool. Or anything else that comes close to its quintessence, Qwghlmian wool.

Optional, depending on climate: a summer lighter-weight version, maybe of a tough linen and hemp fabric.

In my humble opinion, the tweed suit can work for anyone. There are many tweeds, the Scottish part of me would like to think there’s a tweed and way to wear it for everyone. It doesn’t have to be this, for women, for example:

Dame Maggie Smith is always a good role-model to follow, not least in costumes for various roles in films. Here she is as Miss Jean Brodie, a female parallel of sorts to the late great Robin William’s John Keating in Dead Poets Society: both films inspired generations of future teachers, at all levels. (I admit to this, freely. DPS rocked my world, changed my life. Second-last year at secondary school, saw it when it came out, as news of it spread amongst us by word of mouth; spot on timing, just before submitting undergraduate applications in the fall of 1990.)

Anecdote: I wore a grey herringbone tweed trouser-suit to interviews for PhDs; this was back in the day when, after the application process, and prior to being given offers, you went through Visits. Admittedly, this was cheap tweed and actually two separate unrelated pieces. And accessorised. Leopard-print fake-fur scarf and gloves. I have no idea if clothes helped, and would prefer to think they made no difference either way, but I reckon that at least they were not a hindrance: I received offers, including the one that I accepted, from a wonderful idyllic possibly perfect institution.

With great agedness and hard wear, tweed of an exceptionally hairy hoary kind may eventually attain the venerable status and lofty condition of a Medieval relative, the hair shirt:

–and, working in symbiotic relationship with its host, becoming as one, an academic may thus attain higher states, sanctity, sublimation. All very appropriate to this very night, with its permeable borders between worlds.

I was thinking about these sartorial choices in relation to our TA Training conversations because I am, in some ways, in a fortunate position. I have worn black–OK, and some gray, brown, etc. but neutrals, and mainly black–for years. Decades. Partly as it makes life easier first thing in the morning: no issues of mismatches. Partly because it’s easier to keep clean, or at least, to maintain an impression of being less dirty and scruffy. I deal a lot with colour in some areas of work, and get physically itchy and hive-y around too much colour, too many colours, the wrong colours. I have been known to get headaches if wearing white trainers (as they zoom in and out of peripheral vision), setting on very rapidly if stripes, coloured laces, and fluorescence are involved. I am simply happier in black. And black fits very well with any job involving public performance.

I’ve actually dressed much the same way since I was a graduate student myself, and before then. I’ve also always opted for occupations which avoided Business Drag. This had been lucky. Not all are that lucky. I thank my lucky stars every day that I don’t need to worry about clothes the way other people do in other kinds of work.

So here’s what I do. If I’m spending a day reading and writing in my office or at home, or in a library–so long as it’s not the sort of library where I have first to be allowed to pass by custodians, where I need to do more than have the right electronic card to swipe–I wear anything I want. Actually, my ideal option would probably be pyjamas, padded cycling shorts (or something else that gives me extra posterior cushioning), and a dust-sheet on top.

If I’m in meetings, it’ll be a finer-tuned exercise: I tend to opt for a somewhat more structured variation on Basic Black, aiming for visual emphasis not being on clothes but on what I’m saying, and thus on the head and hands. I guess an extreme version could add very bright lipstick and nail-varnish; why not theatrical masks?

If I’m teaching (which is what most of my job involves) and otherwise dealing with students (office hours etc.), then it’s a less-structured Basic Black but, due to teaching style, it has to be something comfortable that I can move around in a lot, looser (but not so loose that an item catches on things) and of solid construction. This last element is vitally important to unimpeded arm-waving, gesticulation, miming, and other movement where you really don’t want to fear that clothes are going to rip or fall apart.

The same on solidity goes for shoes; my work involves walking several miles a day, flights of stairs to classrooms, and walking to and from work. Also, I can’t (and am not supposed to, and politically object to) wear fancier high-heeled shoes. My preference is for flat boots, especially right now in the Vancouver rainy season. Boots are not only a practical necessity but central to the female academic costume and, played well, empowering in all the right and proper ways.

I don’t wear jewellery or scarves when teaching or talking, after incidents in the past when they got tangled in hair and nearly killed me. Having shorter hair now probably means I could rethink that. I tend to avoid exposing cleavage, but that’s partly for practical reasons: for half the year, I’m colder and prefer more coverage; all year round, I need to cover all exposed flesh in sunscreen for medical reasons (redhead, flammable, had Thing removed some years ago, high risk for skin cancer). Good sunscreen is expensive, and slathering it all over large areas of scantily-clothed self works out more expensive (and is actually less protective) than wearing clothes. Practicality and health are, in my particular case, higher-priority criteria than political arguments for or against displays of feminine assets.

Juliana Morell (Doctor of Laws, 1608): one of the contenders for First Doctrix Ever and, less controversially, for Strictest-Dressed Doctorest

I also often have students from a variety of different backgrounds, so out of respect for cultural and religious difference, neutral clothing is I think a good idea. My aim in teaching is to help to create a good happy harmonious classroom atmosphere, to do what I can to make everyone there feel comfortable. I am there as a guide, catalyst, and intermediary; go-between, liaison, contact, entremetteuse; in an interactive learning experience (if you’ll forgive me what looks like NewSpeak, meant here in its proper common sense). I am not there to be the centre of attention: it’s not about me, it’s about the things we are learning.

This is “learning-centred learning.” It is what we—the university, that is, faculty and students in a collegial community of knowledge—what we do and what we are.

There should be some authoritative associations, but not as a Power in my own right, nor in a System as a Boss disciplinarian maintaining power-hierarchies. No. I am here as an intermediary for Authorised Learning, part of The Idea Of The University and on behalf of The Higher Powers of Knowledge, to help others to meet Authors and The Authority that is The Great Goddess of many names with whom we are communing together: Scientia, Sapientia, Sophia, Minerva, Wisdom. Access to her is open to all: she listens and talks with all, not just those with advanced degrees. That’s how we PhDs advanced to higher knowledge in the first place. None of us are born knowing; born questioning perhaps, well on the way in The Great Art of asking the right questions.

It was a path of long study and conversation.

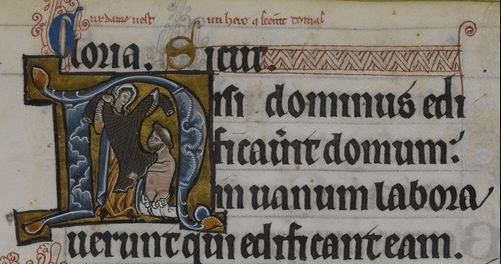

Transformative learning-centred learning:

Christine de Pizan and the Cumaean Sibyl on their journey, a feminist refashioning of those of Boethius, Jean de Meun, and Dante: second-last stop, meeting and discussion with Lady Reason; last stop, diplomacy to save the world

So my appropriate academic garb should resemble that of a priest or oracle.

The end result is rather medieval…

And here is one of the commonest online images of a Medieval academic gown:

My first BA was taken at a university that had been founded in the Middle Ages. It was still Medieval in some ways. One of them was the wearing of gowns. Some profs still lectured in them; some wore them every day, an extra layer under (more convincingly sincerely normal) or over (more possibly ostentatious or pretentious) their coat. Students didn’t have to wear them all the time any more, nor indeed at all in certain colleges. The version I wore was the very simplest kind, knee-length, with open sleeves which were, as you might imagine, very handy (non-kinky (before you even start thinking it), ritual use of the different openings aside):

Some people dislike gowns. Some dislike is because of perceived associations with social elitism; via certain institutions, markers of aristocratic or other moneyed power of the same order as black or white tie, the extreme versions of The Suit in barely-changed Victorian Imperial hauteur. But remember: in some cases, we are talking about institutions that have a long meritocratic, anti-elitist history; scholarships, subsidised student resources (food, accommodation, basics like water and computing); something precious which is in danger of being completely lost, with the fallacious conflation of merit with elitism and entitlement, the rise and rise of anti-intellectual culture, and the threats to all teaching of history.

Gowns, you see, are brilliant. They can cover up a multitude of sins, you thrown them on over anything (or nothing; or, in the case of a friend’s 21st birthday party, you can put one on a bikini-clad blow-up doll and sign her into Hall as a guest), even cheap ones are very stain-resistant, whiteboard-marker is invisible on them, you can use and abuse them as an amusing extension of your chalk-board, and best of all: they flap. Batman has nothing on the majestic glory of the gown. Or its comedic potential. Good old-fashioned black gowns like ” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>the everyday “undress” doctoral ones of Oxford and Cambridge are The Way. Far from a quaint bizarre relic, gowns are very fine useful things.

Look at this beautiful, classic piece from Eileen Fisher’s 30th anniversary “icons” collection. Pricey, but still cheaper than my “faculty quality” doctoral outfit would be (and less orange, two reasons for not having bought it… which–in advertising, sales, and marketing terms–makes me “not quality faculty”). It owes as much to the gown as it does to the kimono and other simple flowing robe-shapes:

Anecdotes: when I was an undergraduate, we wore gowns for a small number of ritual occasions: matriculation, graduation, that sort of thing. In my college, we also wore them for Formal Hall (cheap usually not-very-good food, very long Grace), which was as I recall every week-night plus Sunday. My gown was a cheap thinner second-hand one (£5). I have no idea how old it was when I bought it, and it was still resellable at the end of my three years, for the same price. That’s sustainable economics for you. The gown resisted everything: thrills, spills, falls, soup, and even the pats of butter that occasionally fell from the rafters. These had been supplied during wartime and post-war rationing, later on as an attempt to reduce the European butter mountain; but supplied to excess for some odd reason (there was a story behind this), and much of this surplus supply were older and rancid.

In an amusing game, pats of butter were opened slightly (thus ascertaining usability vs rancidity) and pinged up by students–my college being strong in engineering–using improvised catapulting devices, which had to be made on the spot using the available materials: cutlery, crockery, any useful springy food, etc. All of which would then be returned to its normal function afterwards: good recyclable tidy fun. Well-pinged rancid butter–the more rancid the better–would stick for a long time. The first time one dropped on me was a moment of awe and wonder: direct contact with generations of predecessor-students, mediated by the thirteenth-century structural fabric of the Hall itself.

Butter from the 1940s is apparently still there, awaiting its moment for dramatic descent from the heavens. And in my day (early 1990s) we still had rice-pudding races, a game passed down the generations and with thanks to the kitchens for never changing the glutinous sticky recipe: points for angle of tilt to one’s dish, length of time before the rice moves at all, the winner being (on an outstanding rice-pudding night) that individual who holds their dish of rice-pudding upside-down for the longest before its contents start to fall off. Losing a drop meant automatic disqualification; and, of course, cleaning it up. That, at least, was the good civilised version of the game played with friends who were engineers, NatScis, CompScis, etc. (with a handful of us lawyers and the more left-wing historians thrown in for good measure).There were, as you might imagine, some proto-Suits who played a different version of the game with their set. They thought it was much more amusing just to throw food around, any food, and who would never have considered cleaning up after themselves. Says it all…

Butter (and indeed rice-pudding) in hair was a different matter entirely, and not a moment of wondering wonderful happiness. For this may have been the UK, and one of its older-fashioned parts, but it was not one that still practises the ancient use of animal fats for keeping oneself moist, weatherproofing, and cosmetic purposes such as the decorative sculpting of hair. We tend to leave that to urban hipsters and imported neo-Druid types.

Makeup and hair are touchy topics, especially for women. That’s probably the understatement of the year and is not meant to sound facile or facetious. Factors contributing to complications: individual character and inclination, political position, context / environment / culture and others’ perception, how much one cares about those latter external factors, how much one feels one ought to, how much they actually factually matter. I am lucky, again partly by practical reasons that rule some things out: skin that reacts to a bazillion things and that does not match any foundation, plus laziness and a greater need for an extra cup of coffee in the morning before leaving for work. There’s still some masking, but it’s minimal/ist and not a mask so much as a way to let my inner “true” dark-lashed self break through the gods-given ginger surface. Inner nature vs nature vs nurture. But on the West Coast in 2014, I have the impression make-up is for most intents and purposes a matter that’s somewhere between “don’t ask, don’t tell” and a non-matter of less general social import–and background basic free individual expression–as one’s preferences in smartphones or caffeinated (or non-) beverages. And I would hope that might become the usual given: free individual creativity and celebration for all, and free from the repressions of social construction.

There is some splendid Old Occitan and Old French poetry on make-up, by the way, mostly amongst the more hilarious tensos and partimens. (I may post a few on this present blog one happy day for extra bonus fun.)

Now, hair. Which was really why I started writing this post in the first place, before digressing into clothes and make-up. I wanted to share a joy that has improved my hairy life over the last month or so. It has made me a happier person with happier hair. If his marvellous miraculous discovery is useful to anyone else, then I will be all the happier. Spread the joy…

Like the other trappings of external appearances, “professional” hair is subject to the personal, the political, and the practical. Now, we of the ginger persuasion (and reclaiming “ginger” as a mark of pride, wrenching a good spicy fragrant word from the grubby mitts of pernicious gingerists) get a lucky break: our hair is sufficiently distinctive that it will stand out whatever you do (try running away from naughtiness at primary school: epic fail). It’s a minority hair. Even the most negative of its cultural connotations focus on its weirdness. The usual witches and Viking berserkers aside, consider another, finer medievalist model, the good Princess Merida:

Fiery, feisty, wild, Very Other, unpredictable. Red hair and all it carries with it: a brilliant and liberating gift. One cannot but stand out, in a way that is not artificially aggressive or self-centred, whatever one does. And the weirder associations don’t seem out of place in academia. I did, however, cut my hair: the decades of Pre-Raphaelite associations finally got my goat. Especially as a Medievalist. Sure, one could have done other things; and I had other reasons to cut it (recurring stress-related scalp eczema necessitating very drying shampoo, mourning, one interpretation of feminism, laziness); I might regret it. But it’s hair, it grows, and it’s only hair after all, not a major body modification like removing a limb. Heck, if I weren’t such a fainting timorous wee beastie I would be covered by tattoos by now…

If one’s hair happens to be in the least bit wavy, though, it does all sorts of curious things when cut short. Not unexpected, if one comes from a family of curly-haired people. Hair politics then become more resonant: clearly, there is a political and ethical imperative to embrace the curl and not flatten it out of existence, tamed by an arsenal of potions and lotions and torturing devices. In solidarity with all curly-haired people, especially those who have suffered oppression when hair is connected to race.

There’s quite enough pain and agony inflicted on people around the world, now as over previous centuries, by forces of repressive authority. Deploying instruments of torture on onself, deliberately, adds insult to injury. In solidarity with the repressed, and in memory of them at this time of All Souls, please, good people, please think again before you use straightening-irons. Think of what these irons are descended from. Think of the millions of victims of torture, over millennia.

These things are evil. Also, they have featured in some rather horrid nightmares with which I will not scare you (even if you persist in using straightening-irons despite everything I’ve said).

I am a boring practical creature, and a lazy one with a dislike for any avoidable fuss and bother. Uncontrollably frizz and tangles can be uncomfortable and problematic. Such hair may also cast imputations on one’s character, organisational competence, and professionalism. I’m honestly not sure where to draw the line between “intellectual who is thinking and working and living more important things” and “mad mess.”

But. I believe I may have found a compromise. Wave hello to:

All three items are pricey, but last a long time. The first two items take moments to use and smell lovely in the shower. Palmarosa, bergamot, sandalwood. The third item (same lovely smell) is applied to towel-dried hair–a teeny tiny quantity, smaller than a grain of rice–rubbed between palms of hands and sort of waved through hair, especially the more unruly bits, in a vague and haphazard manner. No devices or heat needed: leave hair alone, exit bathroom, head for coffee-making apparatus of choice and get on with the more important things in life / the morning. The stuff dries invisibly and imperceptibly. There is no scent left afterwards that might possibly offend or irritate other people. I will usually brush hair at some point later on once it’s fully dry.

The resulting hair is, as it says on the bottle, smooth. It is neither dry nor greasy. It is not frizzy. It is not flat. It is still wavy. It definitely still has bounce, and waywardness; has life and independence. My hair and I are enjoying a better life together. Not in conflict, and I haven’t threatened the hair with death by shaving in quite a while now. Happy harmony.

Some Medieval alternatives, for professional controlled hair, including the example of Dame Philology herself:

And a nice case of the well-coiffed but wavy (I like to think there might be a full quiff hiding in there too), one of the first women to be granted a doctorate: María Isidra Quintina de Guzmán y de la Cerda (Universidad de Alcalá, now Complutense University of Madrid, 1785):

A lovely lighter robe—the ermine mozetta—and free curls for the Venetian polymath Elena Cornaro Piscopia: mathematician, “oraculum septilingue” (Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic), musician and composer, philosopher, theologian, physicist: laurea, University of Pisa, 1678.

18th c., Biblioteca ambrosiana, Milan

She also has (not in the painting above, but in the stained glass window below) an actual laurel wreath.

Her laurea would entitle her to be called dottoressa. For other people to call one “doctor” and for that to be recorded is key to “being a/the first woman doctor”; or even today, to “being a doctor.” That’s already a first interesting linguistic point: it is that naming by others that makes a thing real. Here’s a second interesting linguistic point in crowning a woman as “a/the first woman academic doctor”: complication by the word “doctor” having different meanings at different time, but a shared etymology and root sense across languages: Latin doceō, to teach & doctor, a person who teaches. The Italian laurea varies across time and institutions and “dottore/dottoressa” would be used until recently (my lifetime) to mean “has the equivalent of a BA and may teach” and there is no formal Italian research doctorate (Dottorato di ricerca) until 1980.

Cornaro Window, Thompson Memorial Library, Vassar College (designed by Dunstan Powell; 1906).

While scholars can often be recognised because they bear some of their insignia—a book of philosophy, a ring or other bodily modification signifying symbolic marriage to knowledge—when did you last see one wearing a gown, a chic cape, or a laurel wreath? Make laurel wreaths stylish again! They look splendid on all head-shapes and hair, and can be worn on top of hats, hoods, and other head-gear.

Beatrice would have worn it at least as well as Dante, and had at least as much right to wear it. Laurel wreaths for all philosophers, poets, and philologists! And other “doctors,” in the narrow and broad senses, in the spirit of the word. Including our scholarly kith and kin in the doctorate’s long prehistory: the learned teacher, interpreter, and commentator called doctor or doctrix; the 12th-c French sense; the 18th-c. German innovation of adding that crucial “philosophiae” that emphasises our love for wisdom by our contributing to it; and so on, all part of the Fifth Estate.

Scholars are not Suits. There is no reason why we shouldn’t mark ourselves, and be remarkable, by wit and whimsy; attracting other future intellectuals to the life of the mind through exhibiting and expressing some joie de vivre.

Let us not forget the sartorial model proposed by the late great philosopher, Professor G.E.M. Anscome:

To the practicality of the medieval academic gown (and/or cape), and the idea of a laurel-wreath renaissance, I would add the whimsical velvety delight of the doctoral Tudor bonnet (or “tam” for North Americans; and boy, Robbie Burns would be amused), with all its coquettish expressiveness. May they be revived, or at least their influence deliberately, consciously incorporated into real academic working wardrobes: and down with corporate, unconscionable suits!

Which leads us to this merry seasonal delight:

Happy Samhain. If you’re undecided on a disguise for tonight, consider being an academic and/or a redhead. Some of us–I hope, most–like to see, and warmly welcome, new members of gingerkind. You might like being ginger: it may bring out other sides of you, unexpected ones, in unexpected ways. Try it for a night, but beware, you might want to stay that way …

I leave you with a splendid costume option to work on for next year: Hildegard of Bingen in full ecstatic revelatory mode, an effect that could be represented by red hair (or part of a recycled Zoidberg costume?) and hair-spray:

Epilogue:

Procrastinate in style: why actually finish the work you were supposed to do on Friday evening, when you could write a few thousand words instead? And then why not add a few more and get over the 4,000 on the Sunday, as a warm-up to getting on with that work that needs to be done by Monday morning? And to do so in the ideal writerly garb: pyjamas and dressing-gown. The latter must be hooded and have large pockets and sleeves wide enough to fold one’s arms through them properly; in appropriately monastic and clerical style