I thought we’d check on Bevis today. Bevis is a dog. He died in 1842 and rests in Duxbury woods, south of Chorley. Given all the rain we’ve had, I thought it was prudent to set out wearing Wellington boots. I have my own story about Bevis, which I’ve written about elsewhere. He’s far enough away in time to be recruited as myth, and I’m sure he won’t mind. He’s a playful creature, loyal beyond the grave. And we all need someone or something to watch our backs

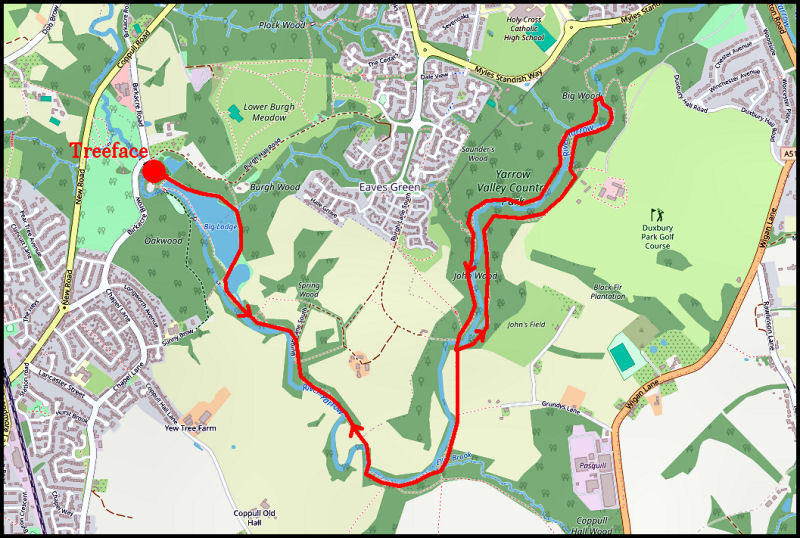

We begin with lunch at the Treeface café, at Birkacre – a cup of tea and a bacon sandwich. The forecast is fair, which seems unlikely, I mean following on from yesterday’s gales, and torrential rain, but then this is a notoriously unsettled season. While we wait for our bacon sandwich to arrive, we amuse ourselves with the Merlin app. We have warm sunshine, and it’s pleasant sitting out. In just a few minutes the app has picked up the songs of great tit, blue tit, thrush, wren, blackbird and chiffchaff. They are going mad for spring.

I’m still a little stiff after my trip to the lakes last week, and a good soaking up Sallows. The hiking boots are still drying out at home, and it’s as well because I suspect they’d be useless where we’re going today. In the deep of the wood, beyond Drybones dam, we discover the bluebells, the anemones and the wild garlic are all in bloom, but subdued somehow. Perhaps a week or so of sun will bring them on, but it’s getting late for anemones, which look to be enjoying their last gasp. As we make way, the weather changes suddenly, the sky darkens and there is a rush of hail.

We lean into a tree, and wait it out. There is the sound of construction, coming from beyond Lowes Tenement, and the vast housing estate that is ripping up pristine meadows, to the west of the Yarrow. I’m told the local council did not want or need it, but were vetoed by central government. Thankfully, it is not visible from this section of the walk. I wrote about this last time I came. You’ll understand therefore why I cannot swing my route through those fields of destruction any more, that in part what we’re doing today is looking to heal the wound to memory by finding another way through this home patch, by lopping off the limb that has gone bad, and pretending it is no longer there. So, we’ll be heading deep into Duxbury wood instead, swinging a loop, then retracing our steps back to Treeface.

While we walk, we’re musing that much of what we believe to be true about our selves and the world, is actually just a story we tell. Much of what we believe ourselves to be is either memory or aspiration, in other words, just something in our heads that we’re forever casting back, into the past or forwards, into the future. Neither exist beyond the notion of being either a memory or an idea.

We talk of living in the present moment, but what is that? How big a slice of time is the gap between the past and the future? Is it a minute? Is it a second? Is it the so-called Planck second, which is zero point, then forty-three zeros and one, of a regular second. This is supposedly the shortest meaningful time period that can be measured. But the present moment is shorter even than that. The present moment is a singularity. It seems, therefore, we exist entirely in our own imaginations, forever travelling this line in time from past to future without ever setting down to rest anywhere.

There’s a crack of thunder and the hail sweeps over us with a soft hiss that finally recedes. We move on, past the lone tree that fell, in my novel of the same name, and was still standing when I wrote Durleston wood. We enter the domain of the old Duxbury estate, now. In places, I measure the mud here at eight inches deep, by the tide-line on the Wellingtons. There is no way around it, heavy going, yes, but at least we’re not concerned the boots will leak, and we’ll clean them up by a quick paddle in the river. Bevis can be hard to locate, but if you stick to the river, refuse to be intimidated by the mud, teased away by dryer looking pathways, you’ll find him.

He looks to be doing okay.

I presume the grave-site is the original one, chosen by the Standishes of Duxbury Hall. The statue is not the original – the original falling foul of vandalism some time in the early twentieth century. The commemorative stone is the original, erected in 1870, the year after a fire that burned half the hall down, and whose inhabitants were saved, according to the reports, by the manic barking of Bevis.

All ye who wander thro these peaceful glades,

Listning the flow of Yarrows rippling waves,

Pause and bestow a tributary tear,

The bones of faithful ‘Bevis’ slumber here,

1842

This remembrance erected by

Susan Mrs. Standish

1870

Remember, the dog died in 1842, which gives us a neat little mystery we could hang a hundred stories from.

As we get older, it’s harder to maintain the integrity of the story, the myth, we think we’re living. The pristine meadows we knew as children are suddenly housing estates. The world we thought we knew suffers the inevitable changes wrought by the passage of time, and means nothing to others who did not know it the way we did. By the time we’ve more time behind us than ahead, we utter that time-worn lament of the old: “I remember when all this was fields.” And it hurts, because we feel our lives are/were special, so many little victories hard won along the way, and yet here we are, our story being erased line by line, meadow by meadow, ferny dell by ferny dell.

What do you say, Bevis old boy?

Bevis says the myth must be renewed, if we are to go on living without regret. He is, after all, named after a mythical character from Britain’s middle-ages. And have I not attempted my own reimagining of his myth? But the founding myths of our lives are laid down in childhood, and come with the magical charge that only childhood can bestow. The world of the adult is less charmed. All the magic has been beaten out of us by the paradigm in which we live. Still, we do the best we can.

Another hail storm sweeps the wood. Fierce one this, and a sudden drop in temperature, too. We lean into another tree, melt into the lee of it, seek its protection a while. The storm passes. We move on. Marsh marigold, anemone, wild garlic, bluebell, chickweed, lesser celandine. All look tired, except for the marsh marigold, which is everywhere perky, as the bogs widen.

Scent of old woodland after rain, now. A few old trees have gone over, tearing craters in the ground, scent of earth, scent of the peaty Yarrow. The river is eating at the bends, undermining paths. Just here, the winter storms have also washed out bits of pottery from a Victorian tip, tumbled them down a stream and in to the river, always worth a look. We fish out several shards, patterned, some with bits of writing – “Made In Engl,…” we invent stories for them, old farmhouse kitchens, cups of tea, Sunday lunches long ago.

We make it back to Treeface, another story there, for what is Treeface if not the mythical green man? I call my sister, who lives nearby. Drive round for a brew and a chat, swap stories. I am no longer a child. No longer an engineer. Those are old stories, no longer serving a purpose. I am a writer of sorts now, and a photographer, marking the changes, while also seeking the unchanging in landscape, and finding a way through it all. That’s fine, it’ll work, so long as I don’t try to big it up too much.

Sure, that’s my story. How about yours?

About four miles, flatish.