Eumenides

Orestes Pursued by the Furies by John Singer Sargent (1921)

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainIntroduction

The Eumenides is an Attic tragedy by Aeschylus, one of the most famous tragedians of classical Athens. It was originally staged in 458 BCE at the City Dionysia, an annual dramatic festival in which playwrights would compete to entertain the citizens of Athens. It serves as the final play of the Oresteia, a trilogy of connected tragedies depicting the murder of Agamemnon and its aftermath.

In the Eumenides, Agamemnon’s son Orestes is tormented by the Erinyes (the “Furies”) as punishment for killing his own mother Clytemnestra (which he did to avenge her murder of Agamemnon). Supported by the gods Apollo and Athena, Orestes receives a trial on the Areopagus in Athens and is ultimately acquitted.

The play, which explores the themes of law, purification, and familial and religious piety, is still widely read today.

Title

The title Eumenides (Greek Εὐμενίδες, translit. Eumenídes) comes from a euphemistic name for the Erinyes, or “Furies”—Orestes’ tormentors in the play. Significantly, however, the term “Eumenides” never occurs in the text; there is thus some doubt as to whether this was the original title.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Eumenides Εὐμενίδες (Eumenídes) Phonetic

IPA

[yoo-MEN-i-deez] /yuˈmɛn ɪˌdiz/

Author

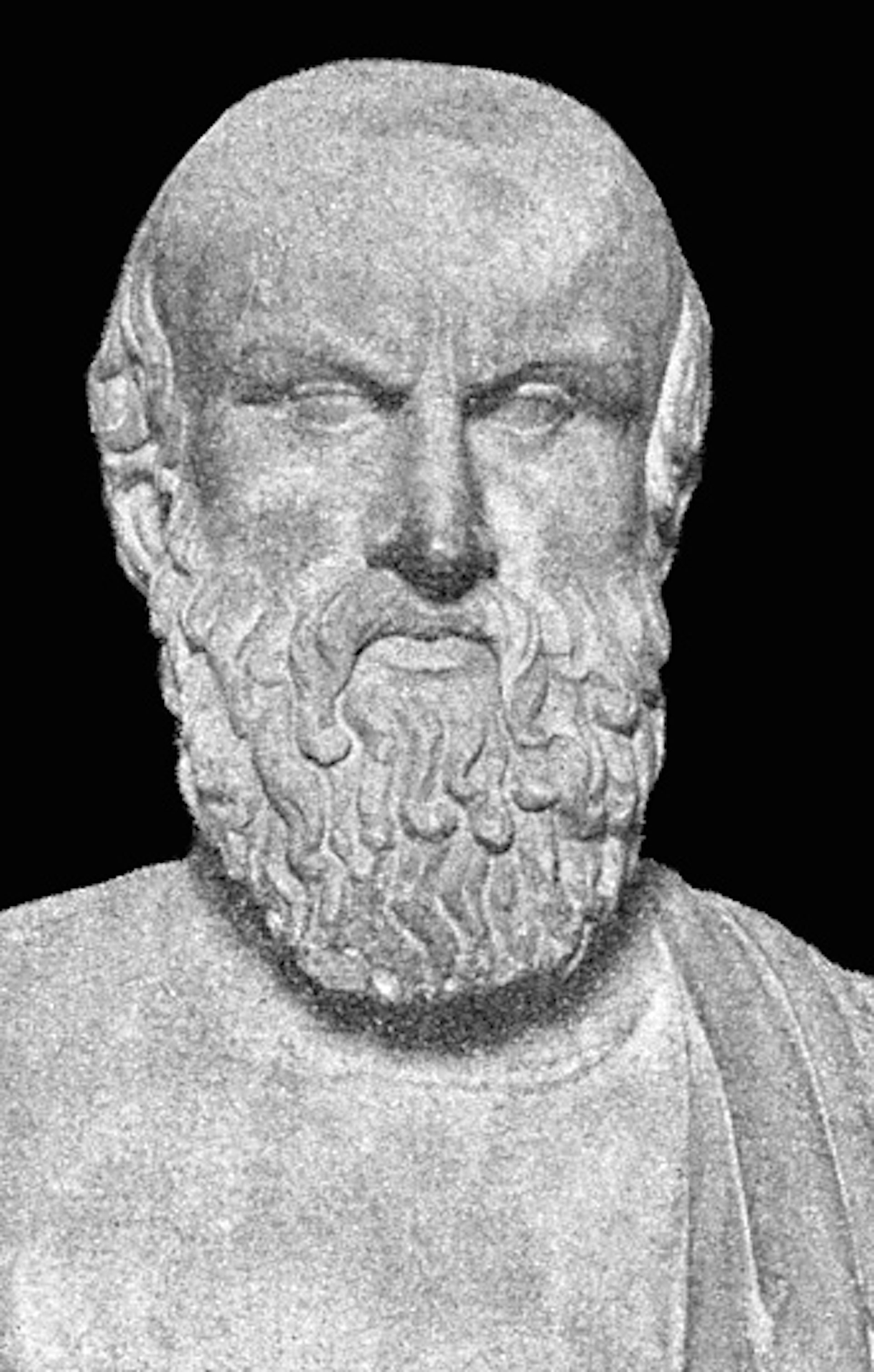

Aeschylus (ca. 525/4–456/5 BCE) was the oldest of the three canonical Attic tragedians (the other two being Sophocles and Euripides). Regarded as the “father of tragedy,” Aeschylus introduced important innovations to the genre and was highly esteemed for his dextrous use of symbolism and metaphor, as well as his exploration of justice and the role of the gods in human life.

A herm, conventionally said to be a bust of Aeschylus (first century CE)

Capitoline Museums, RomePublic DomainFrom the many legends surrounding Aeschylus’ life, we can extract a few details that are probably factual. Aeschylus was born to an aristocratic family from Eleusis (or thereabouts). He began producing tragedies in the 490s BCE, winning his first victory at the Dionysia in 484 BCE. He fought against the Persians at Marathon in 490 BCE and at Salamis in 480 BCE. Around 470 BCE, he visited Sicily at the invitation of the Syracusan tyrant Hieron; he later returned to Sicily and ultimately died there.

Over the course of his distinguished career, Aeschylus composed some ninety plays and won thirteen victories at the Dionysia. He was revered both during his life and after, though by the fourth century BCE his plays were increasingly seen as archaic, especially compared to the works of his successors, Sophocles and Euripides.

Mythological Context

As the final entry in Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, the Eumenides covers Orestes’ experiences following the events of the previous play, the Libation Bearers. In the Libation Bearers, Orestes returns to Argos after a long exile to punish his mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus for their murder of his father Agamemnon (Agamemnon’s death, in turn, is the central event of the Agamemnon, the first play of the Oresteia).

By the end of the Libation Bearers, Orestes has successfully enacted his revenge; but by shedding the blood of his own mother, he incurs the wrath of the Erinyes, the Underworld goddesses responsible for pursuing murderers.

The Eumenides—which begins at an unspecified time after Orestes’ murder of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus—describes Orestes’ journey to Athens. There he is finally acquitted of his crimes through a trial at the Areopagus. Orestes’ acquittal breaks the cycle of violence and retribution that has haunted his family for generations.

While the first two plays of the Oresteia closely follow events from Homer’s Odyssey, the Eumenides is not indebted to Homer in the same way. In fact, the play sometimes contradicts details from Homer’s account. For example, while Homer has Orestes travel from Athens to kill Aegisthus and Clytemnestra, Aeschylus’ Eumenides depicts him coming to Athens only after he has carried out his revenge.[1]

Other key details from Aeschylus’ play—such as Apollo commanding Orestes to avenge his father, and the Erinyes pursuing Orestes after the fact—are absent from Homer’s epics. Aeschylus probably based the plot of his Eumenides on the works of Stesichorus and Semonides, both of whom seem to have had Apollo advise Orestes on how to avenge his murdered father. Apollo’s role in the myth is also hinted at in Pindar’s eleventh Pythian Ode.

Augustan fresco showing Apollo with a kithara from the House of the Scalae Caci on the Palatine Hill in Rome

Palatine Museum, Rome / Dody escouade deltaPublic DomainLater in the play, it is said that Orestes will protect the Athenians after his death. This was probably modeled on the belief, reported by Herodotus, that it was the Spartans’ recovery of the gigantic bones of Orestes that allowed them to prevail in their war with Tegea.[2]

The protection of a specific city from the grave was an important function of Greek heroes, and Orestes represents a magnification of that function, protecting not only his own city of Argos (or Mycenae, according to some accounts) but also allied cities as well (whether Athens or Sparta).

The Eumenides also served another function, dramatizing the origins of the Areopagus—a famous Athenian court and council. The “aetiological” myth, or origin myth, of the Areopagus put forward in the Eumenides rests on a connection between Orestes and Athens that may have emerged quite early in Greek history. Nonetheless, Aeschylus’ Eumenides is the only surviving source to fully flesh out that connection.

Orestes’ trial is not the only aetiological myth connected with the Areopagus. In another tradition, the murder court of the Areopagus was established when the god Ares was tried there for his murder of Poseidon’s son Hallirrhothius, who had raped Ares’ daughter (hence the name of the Areopagus, which means “Hill of Ares”).[3]

The Areopagus in general was tremendously important in the mythology of Athens; it was here, for instance, that Theseus was said to have warded off the Amazon invasion. Thus, Orestes’ association with this specific hill is fairly significant.

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

Neue Pinakothek, MunichPublic DomainOrestes was also connected to Athens via the Choes—the second day of an Athenian festival known as the Anthesteria. It was believed that on this day—which was said to commemorate Orestes’ arrival in Athens—the dead would rise up from the Underworld and visit the world of the living. During the festival, celebrants would sit and drink by themselves.

The Eumenides also serves as an origin story for the cult of the Eumenides—or, perhaps more accurately, for the cult of the Semnai Theai, the “Holy Goddesses.” In fact, the term “Eumenides” never actually occurs in the play (and may not have been the original title), while the cult of the mollified Erinyes has important similarities with the Athenian cult of the Semnai Theai.

The Erinyes were known as punishers of murderers and guarantors of order from the very earliest times; their name is even attested in the Linear B tablets of the Bronze Age. Yet Aeschylus seems to have been the first to identify them with the Semnai Theai, goddesses of justice worshipped in a cave between the Areopagus and the Acropolis.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Aeschylus’ Eumenides, in order of appearance:

Pythia (priestess of Apollo at Delphi)

Orestes (son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra)

Apollo (god of prophecy, healing, and music)

Ghost of Clytemnestra (wife of Agamemnon; mother of Orestes)

Chorus (the Erinyes)

Athena (goddess of war and wisdom)

Second Chorus (Athenian women)

In Greek tragedy, it was conventional for all speaking parts to be distributed among no more than three actors. In the case of the Eumenides, however, scholars disagree on how exactly these parts were assigned.

It is possible that one actor (the “Protagonist”) played Orestes; a second actor (the “Deuteragonist”) played the ghost of Clytemnestra and Athena; and a third actor (the “Tritagonist”) played Apollo. The Pythia could have been played by either the Deuteragonist or the Tritagonist. The jury at Orestes’ trial and various court officers would have been played by additional mute actors.

Synopsis

The play opens in front of the temple of Apollo at Delphi. In the prologue, the Pythia details the history of Delphi as she prepares to open the temple. Once inside, she is alarmed to find Orestes, who is surrounded by the sleeping Erinyes.

Apollo arrives, explaining that his attempts to purify Orestes for murdering his mother Clytemnestra have been unsuccessful thus far. He therefore instructs Orestes to travel to Athens to seek the aid of Athena.

As Apollo and Orestes exit, the ghost of Clytemnestra materializes to awaken the Erinyes. Roused from their slumber, the Erinyes sing their first choral ode (the parodos), in which they censure Orestes as well as the Olympian gods who support him.

Paestan red-figure bell-krater by Python (ca. 330 BCE) showing Orestes (center) at Delphi, flanked by Apollo (right) and Athena (left); one of the Erinyes can be seen above (top center)

British Museum, London / JastrowPublic DomainApollo returns to the stage and argues the justice of his cause with the Erinyes. This debate ends with the Erinyes’ departure as they follow Orestes to Athens.

The second episode shows Orestes arriving in Athens and clinging to the statue of Athena as a suppliant. The Erinyes arrive soon after and confront Orestes, singing the first stasimon.[4] This stasimon features the so-called “binding song” that the Erinyes use to immobilize Orestes.

In the third episode, Athena arrives. She questions the Erinyes and Orestes in turn, then appoints a jury of Athenians to judge the case. The Erinyes sing the second stasimon, insisting on the importance of allowing them to punish sinners as they always have.

The long fourth episode features Athena’s establishment of the Areopagus, the Athenian court responsible for judging murder cases. Apollo arrives to present Orestes’ defense, while the Erinyes act as the prosecution.

Apollo makes the argument that Orestes’ murder of his mother should not be interpreted as kindred bloodshed on the grounds that only the male seed plays a biological role in the birth of a child (the female womb merely serves to house this seed). This argument convinces Athena, who casts her vote with the jurors in favor of Orestes. Orestes is thus acquitted.

This enrages the Erinyes, who are on the brink of unleashing their wrath upon Athens. However, Athena placates them with the promise of new cult honors in Athens. Putting on new crimson robes, the Erinyes thus become the “Eumenides”—that is, the “Kindly Ones.”

In the exodus, a second Chorus made up of Athenian women arrives on stage. They sing as they escort the Erinyes to their new home on the slopes of the Athenian Acropolis.

Style and Composition

The Eumenides was first performed at the annual City Dionysia in 458 BCE. It served as the third play in a tetralogy that contained the Oresteia—a trilogy of connected tragedies about Agamemnon’s homecoming and its aftermath—and a satyr play titled Proteus. The tetralogy won first place in competition.

The Oresteia is remarkable for being the only tragic trilogy to survive intact from antiquity. Unfortunately, the Proteus—the satyr play that completed the tetralogy—is now known only from fragments.

Clytemnestra by John Collier (1882)

Guildhall Art Gallery, LondonPublic DomainThe shared themes of the Oresteia reflect Aeschylus’ rather unique interest in producing connected trilogies (Aeschylus’ successors, Sophocles and Euripides, hardly ever composed these kinds of connected texts). Moreover, as the last of Aeschylus’ extant works (he died only a few years after the production of the Oresteia), the trilogy shows Aeschylus at his most mature.

The Oresteia combines some common features of Aeschylus’ style with more innovative elements. For instance, the importance and involvement of the Chorus, the dense symbolism and imagery, and the preoccupation with themes such as justice and religion are all typical of Aeschylus; however, other features, including the addition of a third actor and the complex staging, are more unique to this particular trilogy.

Themes

The themes explored in the Eumenides continue many of the same threads introduced in the first two plays of the Oresteia (the Agamemnon and the Libation Bearers). These include the themes of justice, retribution, the gods, and gender.

Justice is a central preoccupation of the Eumenides, just as it was in the first two plays of the Oresteia. But whereas the justice of the Agamemnon and the Libation Bearers is largely based on retribution, the Eumenides moves towards a notion of justice as fundamentally rooted in law. Thus, while the Erinyes physically embody the retributive justice of the first two plays, legal due process ultimately wins the day over vendetta.

In exploring the meaning of justice, the Eumenides introduces a conflict between the older generation of gods and the younger one. The older gods, represented in the play by the Erinyes, are primordial figures associated with the earth, darkness, and the power of the mother; their justice is founded on the ideas of blood-guilt and vendetta. The newer gods, represented in the play by Apollo and Athena, are associated with heaven, light, and the power of the father; their justice is founded on law.

This tension between the old and new gods is a central theme of the play. Indeed, the acquittal of Orestes—who is supported throughout by the younger gods Apollo and Athena—affirms the supremacy of the new gods over the old. But the two generations are ultimately reconciled at the end of the play when Athena grants the Erinyes new cult honors at Athens.

A key component of the conflict and reconciliation of the old and new gods lies in the opposition between female and male, mother and father. The old gods are depicted throughout the play as feminine and matriarchal, while the new gods are generally masculine and patriarchal, ruled by Zeus, the paternal god of the sky.

This conflict between the genders maps onto the conflict in Orestes’ parental allegiances: after all, the very reason Orestes finds himself in trouble in the Eumenides is that he murdered his mother in order to avenge his father. In other words, Orestes has embraced the power of the father (represented by the new gods) over the power of the mother (represented by the old gods).

It is no accident, then, that it is Athena who ultimately reconciles the opposing forces of the play. While Athena does, by birth, belong to the younger generation of gods, she is also female, like the older gods. However, her femininity does not manifest itself in the dangerous sexuality that characterizes Clytemnestra in the Agamemnon and the Libation Bearers; in fact, Athena is a virgin goddess and therefore asexual.

This asexuality, which she shares with the bestial Erinyes, allows Athena to find common ground with the old gods. In taking the old gods into the fold of her city, Athena transforms them and further consolidates the power of the new gods and their world order—an order based on justice and law.

The "Varvakeion Athena" (first half of the third century CE), after the Athena Parthenos by Phidias

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / George E. KoronaiosCC BY-SA 4.0The city of Athens itself also plays a central role in the Eumenides. Much of the action of the play is set in Athens—the same location where the entire Oresteia trilogy was first produced. Thus, the Eumenides, as performed in antiquity, would have blended with its physical surroundings.

The play integrated itself with the city on a political and historical level, too. Today most scholars agree that the Eumenides was responding to at least two specific historical events that had taken place shortly before the play was first produced.

First, Orestes’ promise of eternal friendship between his kingdom of Argos and the city of Athens reflects the historical alliance between Argos and Athens that had just been signed in 461 BCE, three years before the staging of the Oresteia.

Second, the Eumenides goes to great lengths to describe the origins of the court and council of the Areopagus—an institution whose powers had recently been diminished by the political reforms of Ephialtes in the 460s BCE. Through these historical allusions, the Eumenides engages with the world of contemporary Athens in a very concrete way.

Reception

The Eumenides had an almost immediate impact on both audiences and other tragedians. Indeed, the entire Oresteia trilogy was quite popular among the ancient Athenians and greatly influenced the works of Aeschylus’ successors. Both Sophocles and Euripides followed in Aeschylus’ footsteps in writing plays about Orestes’ murder of his mother and the consequences of that crime.

In contrast to its importance in antiquity, the Oresteia trilogy was not widely read in the Middle Ages or Renaissance. In the eighteenth century, however, it began to resurface in Europe, with many important productions and adaptations.

More recently, Eugene O’Neill’s 1931 play cycle Mourning Becomes Electra relocated the Oresteia to an American Civil War setting. T. S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion (1939) and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les Mouches (The Flies) (1942) similarly retell Aeschylus’ story for a more modern world.

Today, the Eumenides and the other plays of the Oresteia remain among Aeschylus’ most widely read and admired works.

Translations

Translations of Aeschylus’ Eumenides usually appear together with the other two plays of the Oresteia trilogy (the Agamemnon and the Libation Bearers). The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Smyth, Herbert W., trans. Aeschylus. Loeb Classical Library 146. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926: An old but reliable prose translation. It was replaced in the Loeb Classical Library by a new translation in 2008 but is still available online through the Perseus Project.

Lloyd-Jones, Hugh, trans. Oresteia. London: Duckworth, 1979: An accurate translation with helpful annotations, best suited for more advanced readers.

Harrison, Tony, trans. The Oresteia. London: Collings, 1981: A verse translation produced for performance.

Raphael, Frederic, and Kenneth McLeish, trans. The Serpent Son: Aeschylus’ Oresteia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981: A translation produced for a BBC performance of the trilogy.

Meineck, Peter, trans. Oresteia. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998: A translation produced for performance, with an introduction by Helene Foley.

Hughes, Ted, trans. The Oresteia. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999: A readable verse translation by a distinguished poet.

Collard, Christopher, trans. Oresteia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002: A clear translation with brief commentary.

Burian, Peter, and Alan Shapiro, trans. The Oresteia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003: A readable and accurate verse translation.

Sommerstein, Alan H., ed. and trans. Aeschylus: Oresteia. Loeb Classical Library 146. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008: An accurate prose translation that replaced Smyth’s 1926 translation in the Loeb Classical Library.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Aeschylus II: The Oresteia. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: An accurate verse translation with a brief introduction and notes.

Hinds, Andy, and Martine Cuypers, trans. Aeschylus’ the Oresteia. London: Oberon Books, 2017: A verse translation produced for performance; contains minimal commentary.

Taplin, Oliver, trans. The Oresteia. London: W. W. Norton, 2018: An accurate and poetic translation with a helpful introduction.