Following my lamentation on Hollywood’s representation problem I present the first of an ongoing series exploring white hegemony in mainstream cinema. (White Hegemony Files – WHF)

It could be argued that Woody Allen feels somewhat removed from his Jewish heritage both generationally and by account of his atheism. Despite distancing himself from the religious aspect of his heritage and although he changed his name (which was relatively common for Jewish entertainers,) Allen does not hide his Jewishness in his early days as a stand-up or in his film roles. He draws upon the feelings of alienation and of being an outsider in society. “At bottom he is a proud Jew, but his Jewishness comes from an existential condition of victimhood, not from traditional religious beliefs or behaviours.”[1] This concept of victimhood and of being an outsider is an integral part of the American Jewish experience and appears throughout Allen’s films.

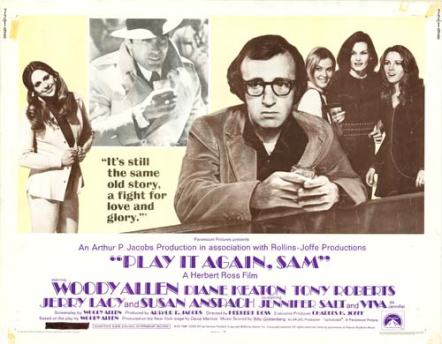

The opening scene of Play It Again, Sam is interesting to consider, it features Allan (Woody Allen) watching Casablanca completely transfixed and enamoured by the film, he stumbles out of the theatre lamenting: “Who am I kidding? I’m not like that I never will be.” This is in reference to Bogart’s sacrifice at the end of the film which depicts the representation of idealised masculinity and demonstrates Allen’s keen awareness of cinema’s role in the representation and therefore the formation of masculine identity. It is fair to extrapolate therefore that Allen is aware of the construction of Jewish identity in his own films and that he consciously creates the Allan character in contrast with the ideal White masculinity of Humphrey Bogart. To that end it is necessary to separate Woody Allen the man from the Woody Allen persona that appears in his films, how alike or unalike the two are is an irrelevancy – the character must be interpreted and analysed as a construction.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Woody Allen’s humour is its self-deprecating nature; this is not an uncommon trait of Jewish comedy, Jack Benny for example ironically satirised the anti-Semitic stereotype of Jewish financial stinginess by playing the character of a miser. The use of ironic self-deprecation in this way confronts anti-Semitism with sophisticated humour, the desired effect is for the audience to ultimately find the absurdity of the stereotype, laugh at it and recognise it as a falsehood. Woody Allen plays up to a different Jewish stereotype that of the ‘schlemiel’ – he plays this type of character in Play It Again, Sam and in most of his other films. The ‘schlemiel’ is “the luckless Jew, an anti-hero whose life was a litany of failure”[2] Woody Allen’s version of the character highlights physical weakness, over emphasis on intellect, neuroses, clumsiness, social awkwardness and general inadequacy; it is the most important aspect of his comedy. Self-depreciative humour can have an endearing effect but when removed from the context of the individual into the context of racial and gendered representations it becomes ideologically problematic.

Throughout Play It Again, Sam Allan’s physical appearance is highlighted as comically ridiculous, he wears thick glasses, has unkempt hair and an awkward dress sense. His physical clumsiness manifests itself in many scenes of slapstick most notably during the blind date scene where his social awkwardness is also apparent and the scene in which a hairdryer blows him around a room accentuates his physical weakness.

The comedy of these scenes stems from an insecurity of appearance, from an inability to behave or look how one would like. The desire for assimilation of the Jewish male here manifests itself explicitly as the imaginary Humphrey Bogart who is an icon of hardboiled masculinity and in complete contrast to the Allan character. Allan however is completely unable to replicate Bogart’s behaviour or to utilise his advice fully until the end of the film, this inability is a constant source of comedy such as the scene in the bar where Allan does an impression of Bogart repeating his line “Nothing a little bourbon and soda wouldn’t fix” before taking a sip of the drink and then immediately spitting it out in disgust and passing out. Another fantasy scene in which he impersonates Bogart successfully and cures a woman of her frigidity is highlighted as comically absurd in that we know the Allan character could never behave in this way in reality.

This constant failure to behave in an acceptable white masculine way suggests the contradiction for Jewish men to attempt to assimilate and to carve out their own Jewish identity within the context of America.

The mise en scène of Allan’s apartment reveals two key character attributes, the many movie posters that cover the walls feature icons of hardboiled masculinity which will be represented explicitly by the imaginary Bogart, what they also show is icons of idealised feminine beauty – that being white women such as Ava Gardner and Lauren Bacall.

The ineffective pursuing of white women by Allan is the crux of the film’s narrative; he is unable to keep hold of his white wife who leaves him in the opening scene, this suggests once again the desire to assimilate and the failure to do so. The other revelation through mise en scène is Allan’s neurosis and hypochondria which is made explicit by the massive amounts of pills and medications – in one scene they avalanche on Allan when he opens a cupboard. The hypochondriac believes there is always something wrong with them, however Allan no real medical ailment, this suggests a deeper psychological problem that could be connected to the problems of identity and assimilation.

Allan’s physical weakness and inadequacy is also fore grounded as sexual inadequacy, he is unable to satisfy his beautiful white wife as a telling one liner reveals: “Did she have an orgasm in the two years we were married or did she fake it that night?” His wife also complains when she is leaving that Allan likes movies so much because he is one of life’s great watchers as opposed to a doer, this essentially marks Allan as so overly intellectual that he is unable to be sexual to a satisfying degree. It could be argued that a tradition of studiousness in both a religious and cultural context forms a large part of Jewish identity; here once again Allan’s Jewishness is presented as problematic, the Jewish attributes that differentiate him do so in a negative fashion.

Allan’s insecurities about his sexual prowess and his physical appearance are fore grounded by the scene in which he fantasises where his ex-wife may be now, he imagines her riding a motorcycle with an attractive and muscular blonde man, she tells him “It’s been so long since I’ve been made love to by a tall, strong, handsome, blue-eyed blonde man.” Allan at the end of this fantasy quips “We’ve been divorced two weeks and she’s dating a Nazi!” The insecurity of Allan over his appearance is made explicit by the contrast of the fantasy biker who is positioned as his complete opposite in looks and attitude – he proclaims that unlike Allan he is a ‘doer’. This sequence in the film reveals a major theme of Allen’s comedy being deep-rooted in insecurities and anxieties over his Jewish identity which is partly defined by his physical appearance and self deprecating humour that functions as a relief from these tensions and in part achieves a sense of assimilation in that the Jewish male is placated, emasculated and desexualised and therefore not a threat to white hegemony.

Relief theory is an important concept in reference to Woody Allen, put forward by Herbert Spencer and Sigmund Freud it contends that negative nervous energy builds up in our bodies and that its release is both a physical and psychological necessity.This idea of the easing of tensions through humour as a resistance strategy is present in much of Jewish comedy and is arguably the product of oppression and alienation. Self-deprecation and resistance are ostensibly paradoxical concepts; self deprecation can be seen as a continuation and reinforcement of hegemony and oppressive ideologies, but when it is considered within the context of relief theory it can be seen as positive.

A scene in the film in which Linda (Diane Keaton) discusses possible dates for Allan with her husband suggests the unsuitability of a beautiful white woman as a candidate: “She’d eat him alive, there would be nothing left but his glasses.” This line indicates that Allan as a Jewish male would not be able to sexually satisfy the white woman, her metaphorical devouring would leave only his glasses – a symbol of intellectualism which is a stereotypical Jewish attribute and one that is played up in the film in that Allan writes for a film magazine and is as discussed a ‘watcher’ rather than a ‘doer.’ The glasses could also be interpreted as symbolic of physical weakness, here then Allan’s sexual inadequacy is linked to his failures as a Bogart like macho man and it is ultimately his Jewishness that is located as the problem. This scene is all the more powerful considering it takes place just before the scene in which Allan fantasises about curing a woman of her frigidity, the juxtaposition of the scenes makes the point of linking sexual inadequacy to Jewishness powerfully.

Allan is feminised through his similarity to Linda, they are both highly neurotic hypochondriacs who regularly see an analyst; Allan’s irrationality is positioned as feminine, the issue of identity in Play It Again, Sam therefore can be considered a crisis of masculinity as well as a racial problem. Allan is also emasculated in the film when he gets into a fight with two men at a bar and is helpless to defend himself, he references this feminisation in typically self-deprecating fashion: “I’m not Bogart, I never will be Bogart! I should get a job at an Arabian palace as a eunuch.” One of the main concerns in the discourse that takes place around issues of race and gender is relationships of power; the feminisation of Allan through the Jewish male stereotype of physical weakness illustrates his position as an oppressed individual.

This idea of power ties in to the Superiority Theory of laughter and raises the question why does Woody Allen use self-deprecation so frequently? Superiority theory suggests that laughter comes from a desire to feel that we are better or better off than others, it is easy to recognise how Allan fits into this theory and how an audience would react favourably to his shortcomings, making him a successful comedic character. The implications of white audiences laughing at a Jewish character like this could be seen as negative and could suppose that Allen loathes his own Jewishness; however the self-deprecation of the Allan character is often from an exaggerated standpoint, taking real concerns and anxieties concerning identity as formulated by race and gender and exaggerating them for transparency necessary for successful comedy. Can these ironic exaggerations actually subvert the stereotypes they draw upon rather than reinforce them and is this why Allen uses self-deprecation so often?

One of the major themes of Play It Again, Sam is the interaction between fantasy and reality, this theme would repeat itself throughout Allen’s career. It most obviously occurs in the film with the imaginary Bogart but there are many instances. Fantasy functions in the film as an exploration of tensions but it also highlights the performance of identity as a manipulated construction rather than as a natural occurrence. Allan’s attempts to emulate the white masculine ideal of Humphrey Bogart and his failure to do so has the ideological implication that as a Jewish male he is an outsider; the exaggeration of Allan’s shortcomings is also a kind of performance since we can fairly assume that due to that very exaggeration Allen was not trying to make the character a realistic representative of the Jewish male, the ideological function of this self-depreciative performance could be seen as positive as Allen is rejecting stereotype through irony.

A telling line in the film comes from Linda who implores Allan to stop the performed image he is trying to create before the blind date telling him: “You don’t need an image, be yourself. The girl will fall in love with you.” This suggests that Allan’s failure on the date stems from his desire to be like Bogart – to assimilate, rather than from his shortcomings as a Jewish male. Here then the need for a true or pure sense of identity is made apparent and Allan’s unhappiness is positioned within this identity crisis rather than a product of his Jewishness. The solution of alienation, it is suggested by this line, is not assimilation and the erasure of Jewish characteristics in favour of characteristics of the white masculine ideal but for the individual to have a strong sense of their own identity and an understanding of how they fit into society.

Allan’s Jewishness is fore grounded in the film in a manner that could be interpreted as self-loathing in its self-deprecation, it could be argued however that it highlights the paradox of assimilation for the Jewish male, in that it represents their difference in a negative light, but this placates them as a threat and can even elicit sympathy from the audience. It gives a strong sense of the need to formulate a particularity of Jewish masculine identity and the perhaps contradictory desire of these outsiders to assimilate. The tension of these opposing desires is articulated in the film through Allan’s inability to behave as Bogart due to his heightened Jewish characteristics which give him a strong sense of identity but ultimately positions him as an outsider. This struggle for identity is articulated by the closing scene in which the ending of Casablanca is mimicked and Allan comes to the conclusion that he has a certain amount of his own ‘style’ – a synonym of identity and that he doesn’t need Bogart anymore surmising: “I guess the secret’s not being you – it’s being me.” Allan’s resolution with himself at the denouement is partly a resolving of tensions of his relationship to his own Jewishness and masculinity and his ability to identify his shortcomings in a comedic way endears him to the audience and ultimately allows him to forge his own sense of identity that is neither stereotype nor fantasy.

References:

[1] Epstein, Lawrence J. “Is There Any Group I Haven’t Offended?” The Haunted Smile: the Story of Jewish Comedians in America. New York: Public Affairs, 2001. 191. Print.

[2] Greene, Victor. “Review: Ethnic Comedy In American Culture.” American Quarterly 51.1 (1999): 154. JSTOR. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Web. 10 Nov. 2010. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041636>