Slender-Snouted Crocodiles

Slender-Snouted Crocodiles

It wasn’t until 2006 that the genus Mecistops was resurrected and once again came into common use for these unique crocodilians.

Africa’s Slender-Snouted Crocodiles fall into the genus Mecistops

The genus Mecistops was originally described by Gray in 1844, though fell out of use by the end of the 19th century when the African slender-snouted crocodile was thought to be a “true” crocodile in the genus Crocodylus. Mecistops was resurrected in 2006 and is now recognized as the sister genus to the Osteolaemus dwarf crocodiles!

Our recent research assessing the genetic and morphological variation found across the distribution of Mecistops (i.e., Gambia to Lake Tanganyika) found that the significant genetic and cranial morphological divergence was highly geographically structured (Shirley et al. 2014). Crocodiles from West Africa are easily distinguished from crocodiles found in Central Africa and, in fact, it was estimated that crocodiles from these two regions have been isolated from each other for over 7 million years.

After several long years, we have finally published a re-description of the genus Mecistops, recognizing two distinct slender-snouted crocodile species: M. cataphractus distributed in West Africa from Nigeria west to The Gambia, and M. leptorhynchus in Central Africa from Cameroon and Gabon east to Lake Tanganyika (Shirley et al. 2018).

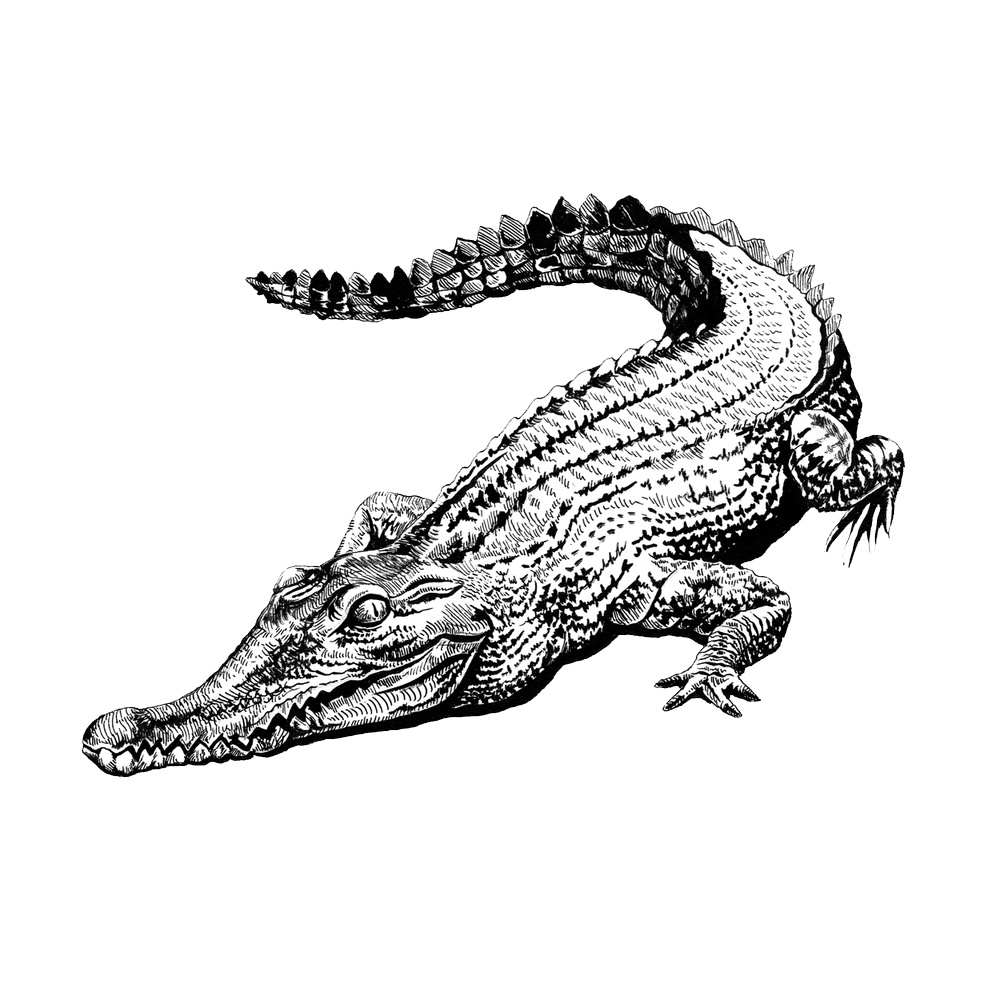

Etymology & Habitat

When Cüvier (1824) originally described this species he did not provide an etymological description of the chosen specific epithet (cataphractus). We assume it came from the Greek kataphraktos (κατάφρακτος) meaning armored, shielded or completely enclosed. Cüvier (1824) also gave this species the French common name “crocodile à nuque cuirassée,” which roughly means “armor-necked crocodile.” Both the Latin and French are presumably in reference to the extra rows of dorsal scutes compared to other crocodiles of the genus Crocodylus.

M. cataphractus is, or at least was historically, widely distributed throughout West Africa from the Niger River delta (Nigeria) west to the Gambia River (The Gambia). Published site-specific records for this species are somewhat abundant, largely owing to the work of Waitkuwait (1985). Interestingly, at least one historic account describes anecdotally how rare this species seemed to be as early as the mid 19th Century (Baikie 1857).

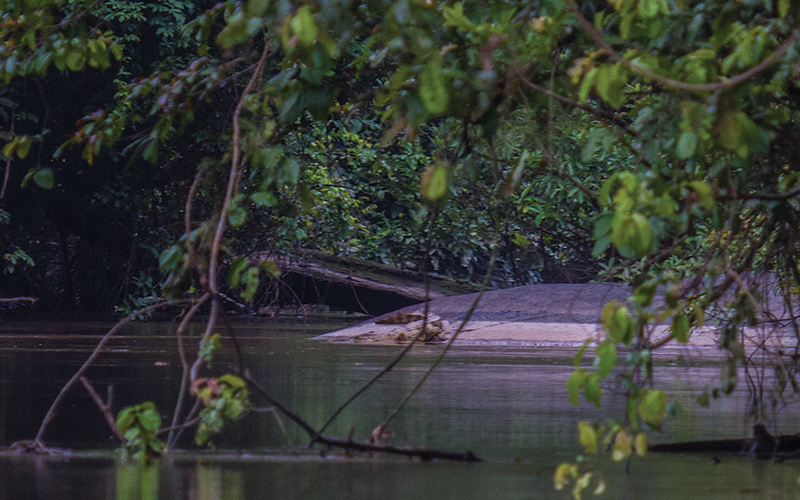

The West African slender-snouted crocodile can be found in medium to large-sized rivers and lakes throughout its distribution. Individuals of all sizes readily use many other aquatic habitats of appropriate size, including flooded forests, “small” forest stream networks, and papyrus and emergent grass swamps at sites where the river and lake margins flood into adjacent terrestrial habitats.

Feeding & Breeding

It might be easy to make the assumption that West African slender-snouted crocodiles are primarily piscivorous (fish eaters), but the reality is that these crocodiles are fairly generalist taking fish, aquatic birds, even larger prey opportunistically like duikers, aquatic chevrotain, genets, civets, monkeys, etc… Fortunately, there are no confirmed instances of this species attacking or predating people.

As part of his dissertation research, Ekke Waitkuwait wrote extensively on the reproductive ecology of West African slender-snouted crocodiles. We know that they are mound-nesting species that construct mound nests within 10 m of the high water mark. Often these nests can be at the base of a big tree. This species was also recorded nesting in a cacao plantation suggesting it is somewhat tolerant of forest replacement habitats.

Observations in Cote d’Ivoire show that slender-snouted crocodile nesting cycle is directly dependent on the rainy season and high water levels. Nests are constructed at the very end of the dry season and eggs are laid 5 – 47 days after the mound nest is constructed. Clutch sizes for M. cataphractus in the wild are quite small averaging 16 ± 7 eggs, and the eggs hatch after an incubation period of 100 ± 10 days.

The nests tend to be remarkably large if you’ve never seen a crocodile mound nest before, but in reality they are not bigger than any other mound-nesting crocodilian nest. Nesting density is low with nests constructed only every 1 – 3 km along the riverbank. Ekke Waitkuwait recorded a 2.2 m female with developing ova and so we can assume this, or more realistically +/- 2.0 m, is the smallest reproductive size in this species.

The following videos (provided by J. Breuggen, St. Augustine Alligator Farm) show the adult pair at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm bellowing. In the first video, the male is performing a bellow that resembles the revving of an engine while the female responded in time with a more typical bellow – almost as if they were duetting!! In the second video, the female starts off giving the revving call of the male before the male responds with a series of more typical bellows – an interesting case of call type reversal!!

Conservation Status

M. cataphractus is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, making it one of the most endangered crocodilians globally. Surveys prior to the year 2000 already recorded it as severely depleted in Liberia and Nigeria, and likely extinct in The Gambia, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, and Togo.

Only populations in Cote d’Ivoire were thought to be not imminently threatened. Since the turn of the century, very little additional survey data has become available for West African slender-snouted crocodiles. Though, data from Nigeria, Benin, Liberia, and Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire suggest that M. cataphractus is all but extinct in the Upper Guinea ecoregion (i.e., west of the Cross River, Nigeria). And, it has not been definitively sited in Senegal since the 1960’s when the carcass of an adult was observed in the Gambia River in Niokolo-Koba National Park by Mr. Gerard Wartraux – owner of the Djibelor Crocodile Farm in Cassamance.

Positive results, however, continue to come from recent and ongoing surveys. We re-discovered this species in The Gambia in 2008 in the River Gambia National Park after it was declared likely locally extinct in 1991. And, surveys in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire are continually turning up new individuals in fragmented populations across the country.

Threats & Population Decline

Population decline in the past has been attributed to habitat destruction and, to a much less degree, subsistence hunting for meat and the commercial skin hunting associated with the decline of Crocodylus suchus populations throughout West Africa.

Hunting for skins in West Africa has fortunately abated, largely as the result of declines in crocodile populations and the availability of skins.

The most significant modern anthropogenic pressure impeding the recovery of M. cataphractus populations is habitat modification combined with the small population paradigm. In other words, we question whether population numbers for this species have declined so much that any small perturbation could push them over that extinction threshold.

Etymology & Habitat

When Bennett (1835) described Mecistops leptorhynchus he did not provide an etymology. However, lepto is derived from the Greek leptos meaning thin, fine, or slender while rhynchos meaning beak or snout.

The Central African slender-snouted crocodile is widely distributed throughout Central Africa from the Gabonese coast and the Sangha-Dja River drainage (Cameroon), north to the Uele River (Central African Republic and Democratic Republic of Congo), east to Lake Tanganyika, including the Malagarasi River drainage on the eastern shore (Tanzania), and Lake Mweru and its drainages (Zambia).

Site-specific records for this species are rare. It may be the unfortunate case that this species is locally extinct from the southern and eastern-most portions of its range (i.e., Zambia, Tanzania, and Lake Tanganyika). Even if not, it is highly likely that these populations are now extremely isolated from the core populations elsewhere in its range.

The Central African slender-snouted crocodile can be found in medium to large-sized rivers and lakes throughout its distribution. Individuals of all sizes readily use many other aquatic habitats of appropriate size, including flooded forests, “small” forest stream networks, and papyrus and emergent grass swamps at sites where the river and lake margins flood into adjacent terrestrial habitats.

This species has even been found in freshwater and slightly saline coastal lagoons, notably in Gabon (e.g., N’gowe, N’dougou, etc…). And, though it seems to be largely restricted to areas around river mouths and away from breaches into the open sea, Olivier Pauwels and others observed small animals on the beach near the Nyanga River mouth (Gabon) on at least one occasion.

Regardless of wetland habitat type, Central African slender-snouted crocodiles are limited to areas that are heavily forested or, in the savannah and woodland northern portions of their range, wetland habitats that have consistent bands of gallery forest (e.g., Plateau Bateke and Lope National Parks in Gabon).

They are also generally not known from isolated wetlands that would require extensive overland forays to reach (i.e., it is highly aquatic and likely only disperses via intermediary wetland habitats).

Feeding & Breeding

It might be easy to make the assumption that Central African slender-snouted crocodiles are primarily piscivorous (fish eaters), but the reality is that these crocodiles are fairly generalist taking fish, aquatic birds, even larger prey opportunistically like duikers, aquatic chevrotain, genets, civets, monkeys, etc… On one occasion this species was observed attempting to predate a comparatively large (50% of the crocodiles body mass) Aubrey’s flapshell turtle (Cycloderma aubreyi). Fortunately, there are no confirmed instances of this species attacking or predating people.

As part of his dissertation research, Matt Shirley had the opportunity to collect data on the reproductive ecology of Central African slender-snouted crocodiles. They are mound-nesting species that construct mound nests within 10 m of the high water mark just like their West African cousins – however, in Central Africa all nests were found at the base of a large tree, and most often shielded from exterior view by a vegetative screen (i.e., shrubs or trees behind which the female would guard the nest from the security of an adjacent pool.

Observations in Gabon and DRC show that this species nesting cycle is directly dependent on the rainy season and high water levels. Nests are constructed at the very end of the dry season, though timing of egg deposition is unknown. Clutch sizes for Central African Mecistops in the wild are quite small ranging from 13 – 21 eggs.

As in the West African species, nesting density is low with only a single nest ever found in any given “oxbow” or within 3 km of the next nest. Matt Shirley recorded a 2.02 m female guarding a recently hatched clutch of babies (which was later confirmed to be the mother genetically) and so we can assume this accurately represents the smallest reproductive size in this species.

Conservation Status

Central Africa is the least studied region globally in terms of crocodile population and conservation status. Surveys prior to 2000 suggested that Central African Mecistops, particularly in the extreme south and east of its distribution (e.g., Angola, Zambia, Tanzania), had already experienced significant declines and the species was recorded as severely depleted in, for example, Chad and Angola. Its status in the Luapula River, Lake Mweru and Lake Tanganyika in Zambia was questioned even as early as 1990.

In 2000 the Malagarasi-Muyovozi Wetland Complex in Tanzania was designated as a Ramsar Wetland partially due to the continued presence of Central African Mecistops. Though, disruption of habitat through removal of riverside vegetation and mortality in fishing nets were believed to have led to significant declines in this species elsewhere in Lake Tanganyika (both Tanzania and DRC sides). In contrast, populations in Gabon, Republic of Congo and Central African Republic were thought to be somewhat depleted but not imminently threatened.

Since then, very little additional survey data has become available for and much of what is available constitutes incidental observations. However, populations throughout Gabon, particularly in the national parks, have been found to be robust and not likely declining.

Similar observations have been made in select protected areas of Congo (e.g., Lac Tele region) and DRC (e.g., Okapi Faunal Reserve and the newly recognized TL2). We also suspect that the vast area of uninhabited wilderness in the center of DRC (e.g., especially in/around Salonga National Park) may support significant populations.

Threats and Population Decline

Population decline in the past has been attributed to subsistence hunting and habitat destruction, as well as the commercial skin hunting associated with the decline of Crocodylus niloticus and C. suchus populations throughout their sympatric ranges, notably in Gabon and DRC.

Modern anthropogenic pressures impeding the recovery of Mecistops leptorhynchus populations include conflict with small-scale, subsistence fisheries (resulting in a reduced prey base and incidental mortality in fishing nets) and habitat modification (where large tracts of forest are being cleared for cacao, rubber, and palm oil plantations or settlements), as well as on-going hunting for the bushmeat market.

Genus Mecistops and History

Bennett, E.T. (1834) On several Animals recently added to the Society’s Menagerie. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Richard Taylor, London, 110 pp.

Bennett, E.T. (1835) Crocodilus leptorhynchus. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 3, 128–132.

Boulenger, G.A. (1889) Catalogue of the Chelonians, Rhynchocephalians, and Crocodiles in the British Museum (Natural History). New. The Trustees., London. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.20951

Cüvier, G.L. (1824) Recherches Sur Les Ossemens Fossiles. Vol. 5 2eme. G. Dufour & E. d’Ocagne Libraries, Paris, 185 pp.

Fuchs, K.H., Mertens, R. and Wermuth, H. (1974) Zum status von Crocodylus cataphractus und Osteolaemus tetraspis. Stuttgarter Beitraege zuer Naturkunde, Serie A. Biologie, 266, 1–8.

Gray, J.E. (1844) Catalogue of the tortoises, crocodiles, and amphibaenians in the collection of the British Museum. The Trustees, London. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.5501

Gray, J.E. (1867) Synopsis of the species of recent crocodilians or Emydosaurians, chiefly founded on the specimens in the British Museum and the Royal College of Surgeons. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 6, 125–169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1867.tb00575.x

Gray, J.E. (1872) Catalogue of the Shield Reptiles in the Collection of the British Museum. Part II: Emydosaurians, Rhynchocephalia, and Amphisbaenians. London.

Ecology and Evolution

Aoki, R. (1976) [On the generic status of Mecitops (Crocodylidae) and the origin of Tomistoma and Gavialis]. Bulletin Atagawa Institute, 6-7, 23–30 [in Japanese].

McAliley, L.R., Willis, R.E., Ray, D.A., White, P.S., Brochu, C.A., & Densmore, L.D. (2006) Are crocodiles really monophyletic? Evidence for subdivisions from sequence and morphological data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 39, 16–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.012

Merchant, M., K. Juneau, J. Germillion, R. Falconi, A. Doucet, M.H. Shirley. (2011) Characterization of Serum Phospholipase A2 Activity in Three Diverse Species of West African Crocodiles. Biochemistry Research International, doi: 10.1155/2011/925012.

Merchant, M., A. Royer, Q. Broussard, S. Gilbert, R. Falconi, and M.H. Shirley. (2011) Characterization of Serum Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Activity in Three Diverse Species of West African Crocodilians. Herpetological Journal 21: 153-159.

Merchant, M., C. Determan, J. Gremillion, K. Juneau, A. Doucet, R. Falconi, M.H. Shirley. (2013) Serum Complement Activity in Two Species of Divergent Central African Crocodiles. Entomology, Ornithology & Herpetology 2(2): 110. doi: 10.4172/2161-0983.1000110

Pauwels, O.S.G., Barr, B., & Sanchez, M.L. (2007) Diet and size records for Crocodylus cataphractus (Crocodylidae) in South-Western Gabon. Hamadryad, 31, 360–361.

Pauwels, O.S.G., Mamonekene, V., Dumont, P., Branch, W.R., Burger, M., & Lavoue, S. (2003) Diet records for Crocodylus cataphractus (Reptilia: Crocodylidae) at Lake Divangui, Ogooue-Maritime Province, southwestern Gabon. Hamadryad, 27, 200–204.

Shirley, M.H. (2010) Slender-snouted Crocodile Crocodylus cataphractus. In: S. C. Manolis and C. Stevenson (Eds), Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Crocodile Specialist Group, Darwin, pp. 54–58.

Shirley, M.H. (2013) Hierarchical Processes Structuring Crocodile Populations in Central Africa. PhD Dissertation, University of Florida, 200 pp.

Shirley, M.H., Vliet, K.A., Carr, A.N., & Austin, J.D. (2014) Rigorous approaches to species delimitation have significant implications for African crocodilian systematics and conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281, 20132483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2483

Waitkuwait, W.E. (1985a) Contribution a l’etude des crocodiles en Afrique de l’Ouest. Nature et Faune, 1, 13–29.

Waitkuwait, W.E. (1985b) Investigations of the breeding biology of the West African slender-snouted crocodile Crocodylus cataphractus. Amphibia-Reptilia, 6, 387–399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853885×00371

Waitkuwait, W.E. (1989) Present knowledge of the West African slender-snouted crocodile, Crocodylus cataphractus Cuvier 1824 and the West African dwarf crocodile Osteolaemus tetraspis, Cope 1861. In: Crocodile Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission (Ed), Crocodiles: Ecology, Management and Conservation. International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland, pp. 260–275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853885×00371

Ancillary Information

Abercrombie, C.L. (1978) Notes on West African crocodilians (Reptilia, Crocodilia). Journal of Herpetology, 12, 260–262. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1563422

Akani, G.C., Luiselli, L., Angelici, F.M., & Politano, E. (1998) Preliminary data on distribution, habitat and status of crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus, Crocodylus cataphractus and Osteolaemus tetraspis) in the eastern Niger delta (Nigeria). Bulletin Societe Herpetologique de France, 87-88, 35–43.

Aoki, R. (1982) [The phylogeny and evolution of crocodilians. I.]. Kaiyoh to Seibutu (Aquabiology), 4, 122–127. [in Japanese].

Aoki, R. (1983) A new generic allocation of Tomistoma machikanense, a fossil crocodilian from the Pleistocene of Japan. Copeia, 1983, 89–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1444701

Aoki, R. (1992) Fossil crocodilians from the late Tertiary strata in the Sinda Basin, eastern Zaire. African Study Monographs, 13, 67–85.

Baikie, B. (1857) On the skull of a species of Mecistops inhabiting the River Bínuë or Tsádda, in Central Africa. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 25, 57–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1857.tb01199.x

Behra, O. (1987a) Etude de repartition des populations de crocodiles du Congo, du Gabon et de la R.C.A. 1ere partie: Congo. Secretariat de la Faune et de la Flore. Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris. Paris, France.

Behra, O. (1987b) Etude de repartition des populations de crocodiles du Congo, du Gabon et de la R.C.A. 2eme partie: Gabon. Secretariat de la Faune et de la Flore. Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris. Paris, France.

Behra, O. (1987c) Etude de repartition des populations de crocodiles du Congo, du Gabon et de la R.C.A. 3eme partie: R.C.A. Secretariat de la Faune et de la Flore. Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris. Paris, France.

Behra, O. (1993) Togo. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 12, 17.

Behra, O., & Lippai, C. (1994) Congo: export of crocodile skins 1970-1978. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 13, 4–5.

Brazaitis, P.J. (1971) Notes on Crocodylus intermedius Graves, a review of the recent literature. Zoologica, 56, 71–75.

Brochu, C.A. (1997) Morphology, fossils, divergence timing, and the phylogenetic relationships of Gavialis. Systematic Biology, 46, 479–522.

Brochu, C.A. (2000) Phylogenetic relationships and divergence timing of Crocodylusbased on morphology and the fossil record. Copeia, 2000, 657–673. http://dx.doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2000)000%5B0657:pradto%5D2.0.co;2

Brochu, C.A. (2001) Crocodylian snouts in space and time: Phylogenetic approaches toward adaptive radiation. American Zoolologist, 41, 564–585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icb/41.3.564

Brochu, C.A. (2003) Phylogenetic approaches toward Crocodylian history. Annual Review Earth and Planetary Science, 31, 399–427.

Brochu, C.A., & Storrs, G.W. (2012) A giant crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene of Kenya, the phylogenetic relationships of Neogene African crocodylines, and the antiquity of Crocodylus in Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32, 587–602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2012.652324

Chirio, L. & Lebreton, M. (2007) Atlas des reptiles du Caméroun. Paris: Publications Scientifiques du MNHN, IRD-Paris.

Cüvier, G.L. (1807) Sur les différentes espèces de crocodiles vivants et sur leurs caractères distinctifs. Annales du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 10, 8–66 + 1 pl.

de Buffrenil, V. (1993) Statut et Repartition des Crocodiles en Guinee. Report to BIODEV “Biodiversite et la Developpement” for the CITES Secretariat,13 pp.

Densmore, L.D. (1983) Biochemical and immunological systematics of the order Crocodilia. In: M. K. Hecht, B. Wallace, and G. H. Prance (Eds), Evol. Biol. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 397–465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-6971-8_8

Densmore, L.D., & Owen, R.D. (1989) Molecular systematics of the order Crocodilia. American Zoologist, 29, 831–841. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icb/29.3.831

Dore, M.P.O. (1991) Crocodile rehabilitation project. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 10, 5–6.

Dore, M.P.O. (1996) Status of crocodiles in Nigeria. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 15, 15–16.

Duméril, A. (1852) Description des Reptiles nouveaux ou imparfaitement connus de la collection du Museum d’Histoire Naturelle et remarques sur la classification et les caracteres des reptiles. Premier memoire. Ordre des cheloniens et premieres families de l’ordre des Saur. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.62017

Duméril, A. (1861) Reptiles et poissons de l’Afrique Occidentale. Etude precedee de considerations generales sur leur distribution geograsphique.

Duméril, A.M.C., & Bibron, G. (1836) II Ordre- Sauriens ou Lézards. I Familie- Aspidiotes ou Crocodiliens. In: Erpétologie Générale de Histoire Naturelle Compléte des Reptiles. Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.46831

Duméril, A.M.C., & Duméril, A. (1851) Catalogue Methodique de la Collection des Reptiles. Gide et Baudry, Libraires-Editeurs, Paris, pp. 1–152.

Eaton, M.J. (2008) National report- Republic of Congo. In: IUCN (Ed), Proceedings of the 1st Workshop of the West African Countries on Crocodilian farming and conservation. La Tapoa, Regional Parc W, Niger, pp. 89–94.

Eaton, M.J., & Barr, B. (2005) Crocodile survey performed in Lac Tele in the northern Republic of Congo. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 24, 18–20.

Eaton, M.J., Martin, A., Thorbjarnarson, J.B., & Amato, G.D. (2009) Species-level diversification of African dwarf crocodiles (Genus Osteolaemus): a geographic and phylogenetic perspective. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 50, 496–506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.11.009

Ferguson, M.W.J. (1985) Reproductive biology and embryology of the crocodilians. In: C. Gans, F. S. Billet, and P. F. A. Maderson (Eds), Biology of the Reptilia, Vol. 14. Development A. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 329–491.

Fergusson, R.A. (2003). Crocodiles in Congo: A feasibility study of crocodile production at Inongo, Democratic Republic of Congo. Gesellsschaft fuer Technische Zusammenarbeit: Eschborn.

Gatesy, J., Amato, G.D., Norell, M., Desalle, R., & Hayashi, C. (2003) Combined support for wholesale taxic atavism in gavialine crocodylians. Systematic Biology, 52, 403–422.

Gatesy, J., Baker, R.H., & Hayashi, C. (2004) Inconsistencies in arguments for the supertree approach: Supermatrices versus supertrees of Crocodylia. Systematic Biology, 53, 342–355.

Gray, J.E. (1862) A synopsis of the species of crocodiles. Annals and Magazine of Natural History. (ser. 3), 10, 265–274.

Gray, J.E. (1863) On the change of form of the head of crocodiles, and on the crocodiles of India and Africa. Report of the first and second meetings of the British Association for the advancement of science, 32, 106–107.

Grenard, S. (1991) Handbook of Alligators and Crocodiles. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL, 210 pp.

Groombridge, B. (1982) The IUCN Amphibia-Reptilia Red Data Book, pt. 1: Testudines, Crocodylia, Rhynchocephalia. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.45421

Groombridge, B. (1987) The distribution and status of world crocodilians. In: G J W Webb, S. C. Manolis, and P. J. Whitehead (Eds), Wildlife management: Crocodiles and alligators. Surrey Beatty and Sons Pty Ltd., Chipping Norton, New South Wales, Australia. 522 pp., pp. 9–21 in Webb, Manolis, and Whitehead.

Groves, J.D. (2012) African Slender-snouted Crocodile Crocodylus cataphractus. In: North American Regional Studbook 2012, 60 pp.

Hakansson, N.T. (1981) An Annotated Checklist of Reptiles Known to Occur in The Gambia. Journal of Herpetology, 15, 155–161. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1563375

Hekkala, E., Shirley, M.H., Amato, G.D., Austin, J.D., Charter, S., Thorbjarnarson, J.B., Vliet, K.A., Houck, M.L., Desalle, R., & Blum, M.J. (2011) An ancient icon reveals new mysteries: mummy DNA resurrects a cryptic species within the Nile crocodile. Molecular Ecology, 20, 4195–4215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294x.2011.05245.x

Jones, S. (1991) Crocodile declines in West Africa. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 10, 7–8.

King, F.W., & Burke, R.L. (1989) Crocodilians, Tuatara, and Turtle species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Association Systematic Collections, Washington, D.C., 216 pp.

Kofron, C.P. (1992) Status and habitats of the three African crocodiles in Liberia. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 8, 265–273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0266467400006490

Kpera, N. (2003) Notes of crocodiles in Benin. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 22, 3.

Lang, H. (1919) Ecological notes on Congo crocodiles. In: K. P. Schmidt (Ed), Contributions to the Herpetology of the Belgian Congo Based on the Collection of the American Museum 1909–1915 Congo Expedition. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, pp. 425–435.

LeGrand, G.N., & LeBreton, M. (2010) An overview of the distribution and present status of crocodiles in Cameroon. In: Crocodiles. Actes du 2eme Congres du Groupe des Specialistes des Crocodiles sur la promotion et la conservation des crocodiliens en Afrique de l’Ouest. UICN – Union Internationale pour la Conservation de la Nature, Gland, Switzerland, 274 pp.

Luiselli, L., Politano, E., & Akani, G.C. (2000) Crocodile distribution in S.E. Nigeria, Part II. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 19, 4–6.

Meredith, R.W., Hekkala, E., Amato, G.D., & Gatesy, J. (2011) A phylogenetic hypothesis for Crocodylus (Crocodylia) based on mitochondrial DNA: Evidence for a trans-Atlantic voyage from Africa to the New World. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 60, 183–191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.03.026

Mook, C.C. (1921) Skull characters of recent Crocodilia, with notes on the affinities of the recent genera. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History ,44, 123–268.

Murray, A. (1862) Description of Crocodilus frontatus, a new crocodile from Old Calabar River, West Africa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (ser. 3), 11, 222–227.

Neill, W.T. (1971) The Last of the Ruling Reptiles: Alligators, Crocodiles, and their Kin.Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 1–486. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1296046

Oaks, J.R. (2011) A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of the true crocodiles. Evolution, 65, 3285–3297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01373.x

Owen, R. (1853) Descriptive Catalogue of the Osteological Series Contained inthe Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. vol. 1: Pisces, Reptilia, Aves, Marsupialia. Taylor and Francis, London, pp. 151–167.

Pauwels, O.S.G. (2006) Crocodiles and national parks in Gabon. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 25, 12–14.

Pauwels, O.S.G., Toham, A.K., & Chimsunchart, C. (2002) Recherches sur l’herpétofaune du Massif du Chaillu, Gabon. Bulletin de l’Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelle Belgique, Biologie, 72, 47–57.

Pearcy, A., & Wijtten, Z. (2011) A morphometric analysis of crocodilian skull shapes. Herpetological Journal, 21, 213–218.

Pierce, S.E., Angielczyk, K.D., & Rayfield, E.J. (2008) Patterns of morphospace occupation and mechanical performance in extant crocodilian skulls: A combined morphometric and finite element modeling approach. Journal of Morphology, 269, 840–864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10627

Pooley, A.C. (1982) The status of African crocodiles in 1980. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 5th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN 2-8032-209-X. 409 pp., pp. 174–228.

Ross, F.D., & Mayer, G.C. (1983) On the dorsal armor of the Crocodilia. In: A. G. J. Rhodin and K. Miyata (Eds), Advances in Herpetology and Evolutionary Biology. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massechusetts, pp. 305–331.

Ross, J.P. (Ed) (1998) Crocodiles: Status and Conservation Action Plan. 2nd Edition. IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland. Available from: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/edocs/1998-012.pdf (accessed 16 April 2014)

Ruvell, R. (1996) Benin – More on C. cataphractus. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 15, 4.

Sadleir, R.W. (2009) A morphometric study of crocodylian ecomorphology through ontogeny and phylogeny. PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1–229.

Schmidt, K.P. (1919) Contributions to the herpetology of the Belgian Congo. Part 1. Turtles, crocodiles, lizards and chameleons. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 39, 385–624.

Schmitz, A., Mausfeld, P., Hekkala, E., Shine, T., Nickel, H., Amato, G.D., & Böhme, W. (2003) Molecular evidence for species level divergence in African Nile Crocodiles Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti 1786). Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2, 703–712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2003.07.002

Segniagbeto, G.H., Petrozzi, F., Aïdam, A. & Luiselli, L. (2013) Reptiles traded in the fetish market of Lomé, Togo (West Africa). Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 8, 400−408.

Shirley, M.H., Oduro, W., & Yaokokore-Beibro, H. (2009) Conservation status of crocodiles in Ghana and Côte-d’lvoire, West Africa. Oryx, 43, 136–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0030605309001586

Shirley, M.H., V. Villanova, K.A. Vliet, J.D. Austin. (2014) Genetic barcoding facilitates captive management of three cryptic African crocodile species complexes. Animal Conservation. doi:10.1111/acv.12176

Simbotwe, M.P. (1993) Crocodile census on Lake Tanganyika. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 12, 17.

Smith, H.M., & Smith, R.B. (1977) Synopsis of the Herpetofauna of Mexico. Volume V. Guide to Mexican Amphisbaenians and Crocodilians Biblographic Addenum II. John Johnson, North Bennington, 49–104 + 6 plates pp.

Steel, R. (1973). Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie. Part 16: Crocodylia. Stuttgart, Gustav Fisher Verlag.

Storrs, G.W. (2003) Late Miocene–Early Pliocene crocodilian fauna of Lothagam, southwest Turkana Basin, Kenya. In: M. G. Leakey and J. M. Harris (Eds), Lothagam: The Dawn of Humanity in Eastern Africa. Columbia Univ. Press, New York, pp. 137–159.

Taylor, P. (1998) More on Crocodylus cataphractus. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 17, 10.

Tchernov, E. (1976) Crocodilians from the late Cenozoic of the Rudolf Basin. In: Y. Copens and et al. (Eds), Earliest Man and Environments in the Lake Rudolf Basin. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 370–378.

Tchernov, E. (1986) Évolution des Crocodiles en Afrique du Nord et de l’Est. Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique., Paris, 65 pp. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0041977x00147366

Thomas, B. (1998) Cataphractus still found in Zambia. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 17, 4.

Thorbjarnarson, J.B., & Eaton, M.J. (2003) Congo and Gabon: Crocodile surveys. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 22, 6–8.

Thorbjarnarson, J.B., & Eaton, M.J. (2004) A preliminary investigation of crocodile bushmeat issues in the Republic of Congo and Gabon. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 17th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, IUCN. The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, pp. 236–247.

Tornier, G. (1901) Die crocodile, schildkroten und eidechsen von Togu. Archiv für Naturgeschichte, 7, 65–88.

Tornier, G. (1902) Die Crocodile, Schildkroten und Eidechsen von Kamarun. Zoologische Jahrbuecher. Abteilung fuer Systematic Oekologie und Geographie der Tiere, 15, 663–667.

Vaillant, L.M. (1898) Contribution à l’étude des Emydosauriens. Cataloque raisonné des Jacaretinga et Alligator de la collection du Muséum. Nouvelles Archives du Museum D’Histoire Naturelle De Paris, (3), 10, 143–211.

Waitkuwait, W.E. (2002) Cote d’Ivoire, project crocodiles. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter, 21, 5–7.

Watanabe, A. (2012) The Ontogeny of Cranial Morphology in Extant Crocodilians and its Phylogenetic Utility: A Geometric Morphometric Approach. Msc Thesis, Florida State University, 192 pp.

Wermuth, H., & Mertens, R. (1977) Liste der rezenten Amphibien und Reptilien. Testudines, Crocodylia, Rhynchocephalia. Das Tierreich, 100, 1–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1443436

White, P.S., & Densmore, L.D. (2001) DNA sequence alignment and data analysis methods: their effect on the recovery of crocodylian relationships. In: G. C. Grigg, F. Seebacher, and C. E. Franklin (Eds), Crocodilian Biology and Evolution. Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty. Limited, Chipping Norton, N.S.W., Australia, pp. 29–37.

Wild, C.J. (2000) Report on the status of crocodilians in the Cameroon forest zone. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 15th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN-The World Coservation Union. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, England., pp. 539–543.