Luther Visualized 13 – Sacramentarian Controversy

October 13, 2017 Leave a comment

The Sacramentarian Controversy

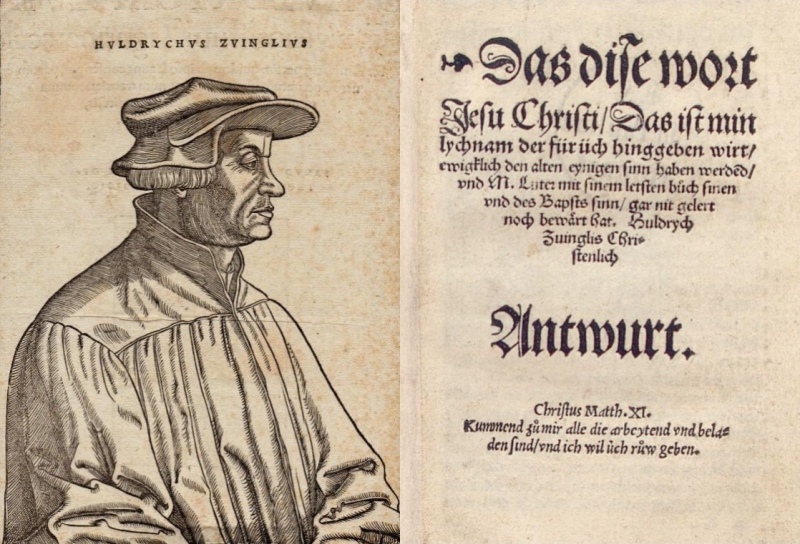

Left: Hans Asper, Huldrychus Zvinglius (Ulrich Zwingli), woodcut, 1531. Right: Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) wins the award for longest book title in the Sacramentarian Controversy: That These Words of Jesus Christ, “This Is My Body Which Is Given for You,” Will Forever Retain Their Ancient, Single Meaning, and Martin Luther With His Latest Book Has by No Means Proved or Established His Own and the Pope’s View: Ulrich Zwingli’s Christian Answer (Zurich: Christoffel Froschouer, June 1527).

Martin Luther often cited the German proverb, “Wherever God builds a church, the devil builds a chapel nextdoor.” Nowhere was that more noticeably true in Luther’s lifetime than in the Sacramentarian Controversy. The two most public opponents of Luther in the controversy were Ulrich Zwingli, a priest in Zurich, Switzerland, and Johannes Oecolampadius, a professor and preacher in Basel, Switzerland. Both of them at first publicly declared their agreement with Luther’s teachings, including his teaching on the Lord’s Supper. But around 1524 and 1525, they began teaching that Christ was not really present, but only symbolically present in the Supper. When a literature battle between both sides ensued, Luther continually based his sacramental teaching on the clear words of Jesus and the apostle Paul in passages having to do with the Lord’s Supper, while Zwingli and Oecolampadius based their sacramental teaching on John 6 (where Jesus’ discourse predates his institution of Lord’s Supper and speaks of faith, not the Sacrament) and on human reasoning.

The controversy culminated at the Marburg Colloquy on October 1-4, 1529. While the in-person meeting did take the vitriol out of the controversy, it also confirmed that an irreparable rupture had divided the evangelical camp. Those present agreed to the first 14 of the so-called Marburg Articles that Luther drew up at the end of the meeting, but the Lutherans and the Zwinglians disagreed on the last point concerning the essence of the Lord’s Supper. As a result Luther said the Zwinglians did not have the same spirit, and Luther and his followers refused to acknowledge them as brothers and members of the body of Christ. And as it turned out, the unity on the other 14 articles was not as strong as it first appeared. The sixth, eighth, ninth, and fourteenth of the Marburg Articles affirmed God’s word and baptism as means of grace, but in the seventh point of the personal presentation of faith (fidei ratio) that Zwingli drew up for Emperor Charles V the following year, he rejected the concept of any means of grace.

Sources

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990), pp. 293-334

Ulrich Zwingli, Das dise wort Jesu Christi / Das ist min lychnam der für üch hinggeben wirt / ewigklich den alten eynigen sinn haben werdend / vnd M. Luter mit sinem letsten buoch sinen vnd des Bapsts sinn / gar nit gelert noch bewaert hat. Huldrych Zuinglis Christenlich Antwurt. (Zurich: Christoffel Forschouer, June 1527)

“Die Marburger Artikel” in Weimarer Ausgabe 30/3:160-171

Ulrich Zwingli, Ad Carolum Romanorum Imperatorem Germaniae comitia Augustae celebrantem, Fidei Huldrychi Zuinglii ratio (Zurich: Christoffel Froschouer, July 1530)

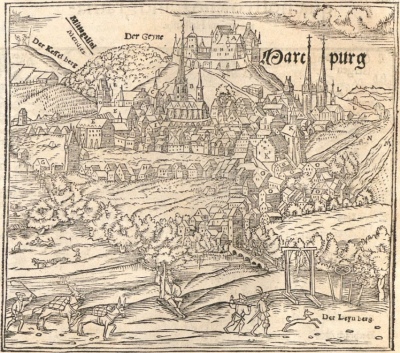

Woodcut of Marburg from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographiae universalis Lib. VI. (Six Books of Universal Cosmography) (Basel: Henrich Petri, March 1552)

The Marburg Colloquy was held in the Princely Castle, pictured here on a hill in the center background. The city of Marburg is viewed from “Der Leynberg” or the Lahnberge, Striped Mountains, in the foreground (east), with St. Elizabeth Church on the right (north) and St. Mary’s Parish Church beneath the castle. The university is to the left (south) of St. Mary’s. The hill behind the castle to the southwest is identified as “Der Geyne” (in a 1572 woodcut from a different atlas, “Der Geine”), and the hill to the south of that as “Der Kesselberg” or Copper Mountain.