Medieval and early modern manuscript acquisitions: A bumper crop for 2017

by Nicholas Herman, Curator of Manuscripts, SIMS

Penn Libraries and the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies are delighted to announce the acquisition of several fascinating medieval and early modern manuscripts over the past year, including an important late-fifteenth-century compendium of astronomical treatises illustrated with numerous diagrams, rotating volvelles, and tables. These new arrivals complement our existing holdings, and provide new and exciting opportunities for original research by students, curators, faculty, and visiting scholars alike. The material encompasses a wide array of subjects, and is especially topical as the new undergraduate minor in Global Medieval Studies launches this academic year. We also look forward to showcasing these and other treasures to a broad audience as Penn prepares to host the Medieval Academy of America annual conference in March of 2019.

What follows is the third in a series of four blog posts

announcing these new acquisitions to the world.

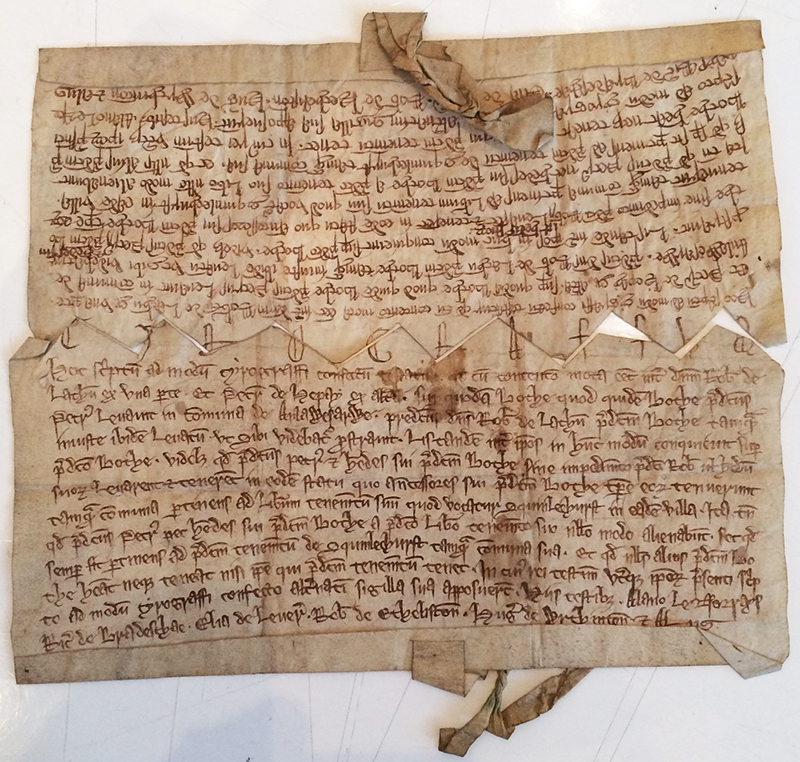

Chirograph document, showing both sides joined together.

Chirograph document, showing both sides joined together.

Penn’s burgeoning community of paleographers—as represented by a revived biweekly PALEO@PENN graduate student reading group—will be delighted to learn of the acquisition of a number of archival documents of the type that may well be encountered in field research. These documents have the benefit of being largely intact. Their purchase does not encourage the dismemberment of codices, and their digitization and detailed cataloguing at Penn makes them newly discoverable by specialist researchers worldwide.

Our earliest new documentary acquisition (above), which dates to the 1270s, records a fairly mundane resolution of a land dispute between a certain Robert de Lathum and Peter de Hepay in Anglezarke, Lancashire (Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 23 Folder 24). The document is, however, highly unusual on account of its format and state of preservation: it consists of two matching sides of a chirograph, a form of medieval legal instrument in which multiple copies of the same text are transcribed and then cut apart along a jagged line.1 In the event of a subsequent disagreement, the parties concerned could match-up their respective copies perfectly to ensure that neither side had produced a forgery. Single copies of chirographs are relatively common, and many thousands are found in European archives and North American special collections libraries. Nevertheless, it is exceedingly rare for both corresponding sides of the document to survive together, which is indeed the case for the new Penn acquisition. More than a mere archival document, this new item bears witness to the physicality of legal proceedings and the interaction of scribal culture with daily life in the later Middle Ages.

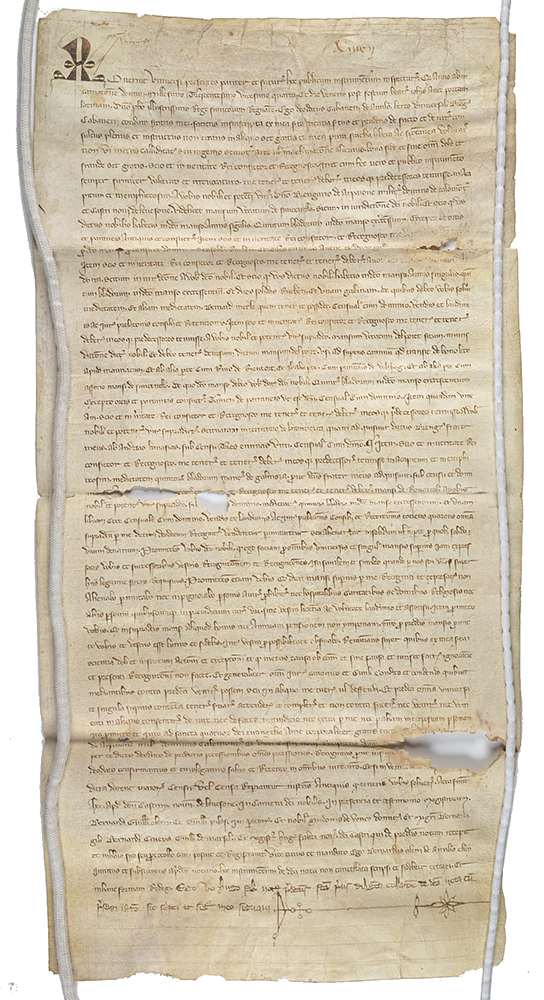

The second document, dated to 1324 and also written in Latin, consists of an homage or acknowledgement of feudal responsibilities by the vassal Dieudonné Cabanier to Béranger d’Arpajon, seigneur of Castelnau-Pégayrols (Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Large, Box 3 Folder 8). The imposing parchment document, which is nearly two feet tall, concerns lands in the Rouergue region of South-Western France, and is a testament to the assertion of power by nobles aligned with the French crown in this restive region, which would pass under English control in the ensuing Hundred Years War.

Dieudonné Cabanier homage, 1324.

Dieudonné Cabanier homage, 1324.

UPenn Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Large, Box 3 Folder 8

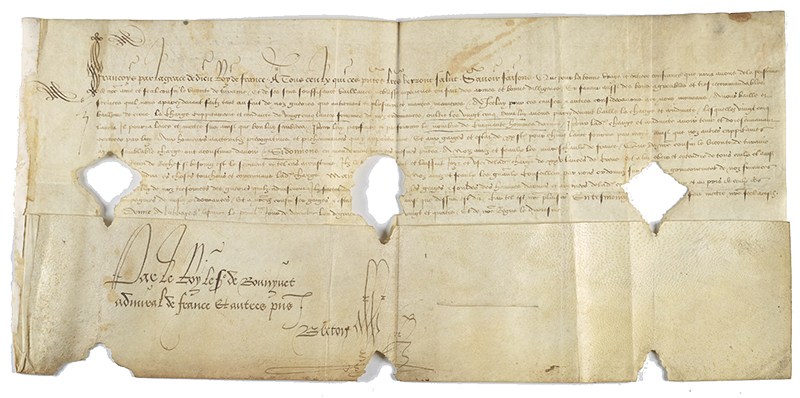

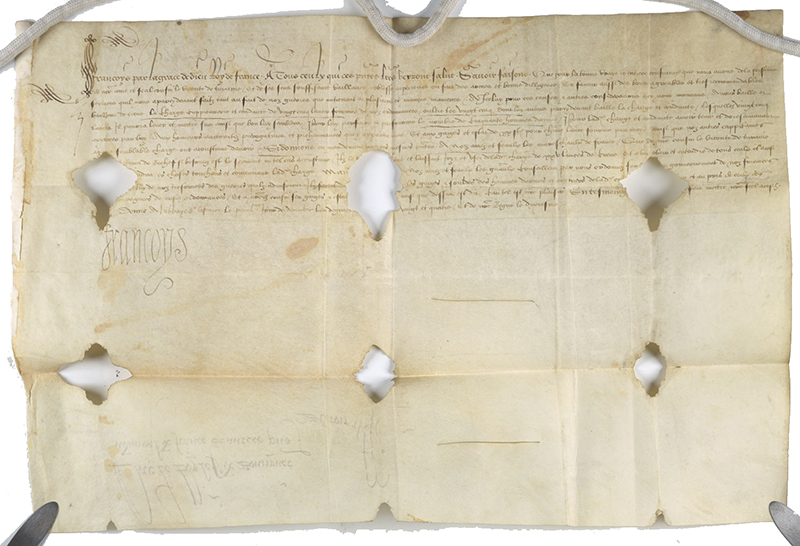

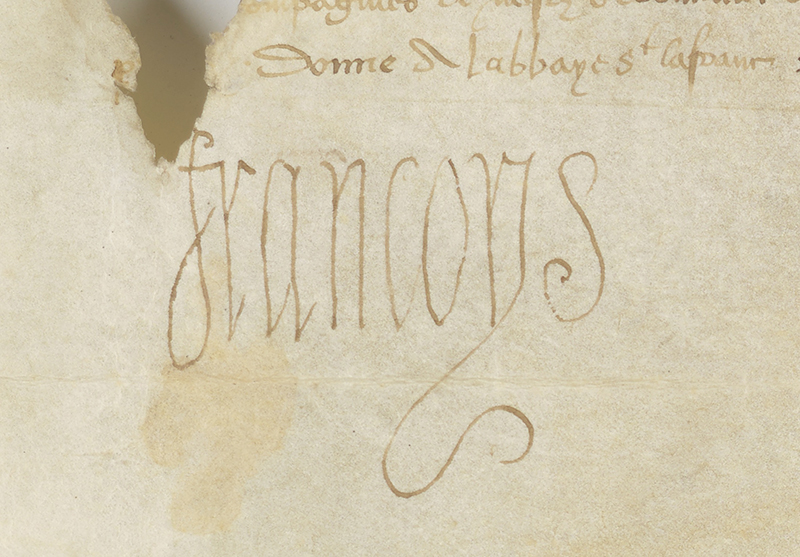

The final archival document, despite some eye-catching damage most likely caused by rodents chewing at the folded corner of the parchment, is exceptional in that it includes the personal signature of King Francis I of France, one of Renaissance Europe’s preeminent monarchs (Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 3 Folder 9). Written in French and dated to December 30th 1524, the document consists of a brevet, or commission, granted to the viscount of Turenne, Antoine de La Tour, seigneur d’Oliergues (1474–1527), bestowing the rank of captain and the charge of twenty-five lances and fifty men-at-arms. Mentioned by name as a witness to the signing of the document is one of Francis’ most favored councilors, the Admiral of France Guillaume Gouffier, seigneur de Bonnivet (c. 1488–1525). The document is countersigned by the king’s principal secretary and minister of finance in these years, Jean le Breton, who was responsible for the construction of the famous chateaux at Villandry and Chambord. Politically, the document attests to Francis’ preparations for a new attack on Milan as part of the Italian war of 1521–26. Ultimately, this military campaign would end disastrously for the King, concluding abruptly with the decisive French defeat at the Battle of Pavia in February 1525. The King was captured and held hostage for several years, and Gouffier was killed. Through this document, we become party to a strategic decision, personally approved by the king, and issued less than two months prior to this ill-fated expedition.

Francis I brevet, 1524, with lower flap folded to show Jean le Breton’s signature.

Francis I brevet, 1524, with lower flap folded to show Jean le Breton’s signature.

UPenn Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 3 Folder 9

Francis I brevet, 1524, with lower flap unfolded to show the King’s signature.

Francis I brevet, 1524, with lower flap unfolded to show the King’s signature.

UPenn Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 3 Folder 9

Francis I brevet, 1524, detail of the King’s signature.

Francis I brevet, 1524, detail of the King’s signature.

UPenn Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 3 Folder 9

You can view the full cataloging entries for the Anglezarke indenture, Miscellaneous Manuscripts. Box 23, Folder 24, the Dieudonné Cabanier homage, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Large, Box 3, Folder 8, and the Francis I brevet, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Large, Box 3, Folder 9, in Penn’s Franklin Catalog, and full facsimiles will soon be available in Penn in Hand and OPenn.

Nicholas Herman

Curator of Manuscripts, SIMS

(with the assistance of Amey Hutchins, Mitch Fraas, and Will Noel)

1 This type of document was recently discussed at the Penn Material Texts seminar by Professor Brigitte Bedos-Rezak of New York University. See also her article entitled “Cutting Edge: The Economy of Mediality in Twelfth-Century Chirographic Writing” in Das Mittelalter 15 (2010): 134–161.

I had a lot of feeds from your manuscript collections to my email. I wonder if you have a conservation laboratory to treat all these very valuable collections. We are a small library with small consetvation laboratory here in the Philippines.

Yes, we have a conservation lab in our library. Here’s an article about it, from when it launched a couple of years ago: https://penncurrent.upenn.edu/features/penn-libraries-new-conservation-lab-preserves-precious-rare-collections