The Whitehall I built in 1983 is the finest bit of boatbuilding I’ve ever done. It began with a commission, so I wasn’t driven by daydreams of cruising as I had been with other boats I had built. For the Whitehall, I focussed on craftsmanship. Halfway through the project, my customer backed out on the deal, but at that point it didn’t change the nature of the work—I was building the boat for boatbuilding’s sake. I was deeply committed to traditional construction and put my best work into the best materials I could find: Port Orford cedar for the planks with mahogany for the sheerstrake, white-oak for the frames, and copper and bronze fastenings. I fashioned the breasthook, quarter knees, and boom jaws from crooks that I gathered and cured. The fruitwood crook that provided the book-matched pair of quarter knees was a once-in-a-lifetime find, perfectly suited to the angle and the curves.

I finished the Whitehall bright. The wood was too pretty and noteworthy in its rarity to hide under paint and I didn’t want to conceal the work I had taken such pride in. I launched the boat without christening it, leaving the naming to a buyer I hoped to find. A young couple living in one of the tonier parts of the Seattle metropolitan area purchased it and over the years I lost track of them and the Whitehall.

Thirty years later it resurfaced when its second owner sought me out. He’d had the boat for several years and loved it but was no longer able to use it. Feeling very strongly that it belonged back with me and my family, he let me buy it at a fraction of its value. Its transom had remained just as I’d made it, unadorned; the Whitehall was still without a name.

Between 1980 to 1987, four other boats I had built for months-long cruises got me through all the adventures that had captured my imagination and ambitions, and I was ready to settle into a career and raising a family. When I brought the Whitehall home in 2014, my kids were on their own and I had just been hired by WoodenBoat. Later that year, the Whitehall became a valuable asset for my work as the editor of Small Boats. It made its first appearance in the November 2014 issue in an article on Beaching Legs and has since appeared in one way or another in at least 54 more articles.

I enjoyed the attention the boat attracted at the launch and in my driveway, but all too often I treated the Whitehall very much like a trophy, brought out only for show and for polishing. That was until Nate and I spent this year’s Father’s Day together aboard it exploring Mercer Slough, a backwater surrounded by a park just south of downtown Bellevue, Washington.

The entrance to Mercer Slough lies under the spilled-spaghetti tangle of elevated off-ramps, on-ramps, and through lanes of Bellevue Way and Interstates 90 and 405. Beneath the widest expanse of concrete, the air is still but the traffic sounds like a gale blowing.

We started out from the launch ramp rowing tandem, but once we reached the slough it was best to take it in with a slower pace. We took turns rowing from the forward station and steering from the sternsheets. The nearest bridge here is part of a bike path that I’ve crossed often, looking down at the slough and wishing I were rowing or paddling rather than pedaling.

The center section of the slough runs straight for 1/2 mile and offers a glimpse of high-rises 2 miles away in downtown Bellevue, visible here just above Nate’s right elbow. At the next bend the city disappears from view.

Like me, Nate is eager to raise sail whenever there’s a breeze that can be put to good use. The spinnaker I made to fly from an oar stepped as a mast has become an essential bit of our kit.

Nate quickly took to stand-up rowing with oarlock extensions. To his left, on the far side of the fence is a blueberry farm that operates within Bellevue’s Mercer Slough Nature Park. Blueberries have been cultivated in the area since 1933.

Nate was in the stern, sailing the Whitehall, when my daughter Alison called to wish me a happy Father’s Day. When I handed my phone to him so he could talk with his sister, he took the phone in one hand and with the other slipped the spinnaker sheets between the toes of his right foot and the tiller-yoke lines between the toes of his other foot.

One of the trails that meander around the park curves through this atypical clearing at the edge of the slough. Nate and I pulled ashore and took a lunch break at a bench situated there. The grass beneath the boat grows on floating sod that sinks when stepped on. I took a short walk along the trail to look in the woods for windfalls that might make a taller mast for the spinnaker. The growth was too thick to venture into and I returned to the boat empty handed.

The upstream extremity of the slough leads to the concrete-and-steel Kelsey Creek fish ladder. It climbs to a culvert that was large enough for the Whitehall, but the baffles in the ladder leading up to it were impassible. (There were no signs of any fish.)

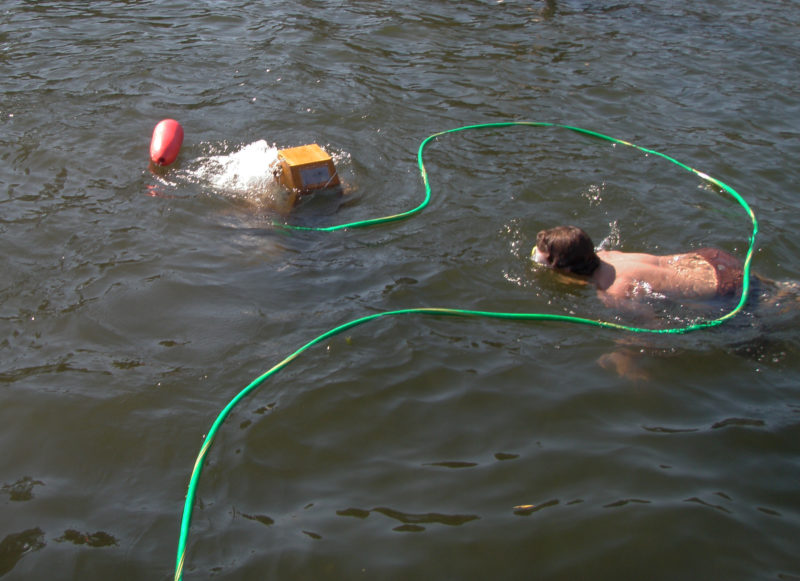

Nate took a close look at the culvert. At the far end, about 40 yards away, there were signs of a cattail marsh. The water was cold, and we decided to turn back.

On our way back from the fish ladder we found a stand of bamboo on land outside of the park boundary. Two of the stalks had fallen and were half submerged. A third arched out just a few feet over the water and I used a serrated folding knife to cut it off a few feet from shore. Nate and I trimmed the branches and we had our new mast.

The north end of the slough loops back to itself around a 1/2-mile-long island. Just 100 yards into our return along the alternative route, we passed under a concrete bridge, low enough that we had to duck to pass under it. Between the concrete girders were steel pipes within easy reach and Nate abandoned ship.

On our passage south back down the slough we found the breeze had switched directions since we last sailed it. The spinnaker went up on the new 9′ bamboo mast to catch the breeze above our heads and pull us part of the way home.

The change in my feelings about the Whitehall and my relationship with it happened as Nate and I tethered it at the bottom of the Kelsey Creek fish ladder. I had only one fender and, before I could get it properly situated, the gunwale grated against the rough concrete wall. The gouge in the oak outwale would leave the boat scarred, but I realized that it would be a memento of a day I’d be happy to remember. My own scars have made the events that created them impossible to forget: the crescent scar on my left index finger I got while learning to whittle when I was 10 years old, the stitch-puckered scar on my right knee where a scalpel-sharp flake of obsidian sliced into it while I was making arrowheads at 14, and the pale V at the base of my right thumb I got at 23 when I was running around Green Lake, tripped and tumbled, gored my hand on a jagged edge of broken concrete, and fell into the lake.

The only scar the Whitehall had carried before Mercer Slough is one that you might not notice. It’s a scarf joint 18″ back from the forward end of the third plank up from the garboard on the port side. I’d split the plank’s hood end while trying to nail it into the stem rabbet without steaming. I had to patch on a new piece. For the 39 years after I’d launched theWhitehall, it had been so gently used and so well maintained that there wasn’t another scar anywhere, no visible sign the boat had ever been subject to the mishaps that are inevitable when venturing out into the world. It’s tempting to coddle beauty, but it comes at the expense of character.

My other boats have scars that bring their histories to life. My sneakbox LUNA has a patch on the bottom where I hit a submerged rock when I stopped on the muddy Kentucky shore of the Ohio River to meet Shantyboat legends Harlan and Anna Hubbard. My Gokstad faering ROWENA has a gouge in the garboard where she slipped off a rail cart at the end of a remarkable portage across Alaska’s Admiralty Island. One of my Greenland kayaks has a patch where a harpoon I’d thrown during a traditional skills demonstration didn’t make it past the foredeck.

I’ll still take good care of the Whitehall, but I’ll seek out more opportunities to enjoy using it with my kids and those close to me. We all have scars, boats and boaters alike, and with its recently gouged gunwale the Whitehall seems more like a member of the family just like BONZO, HESPERIA, and ALISON, the other boats in our fleet that share in making memories. It may be time to give the Whitehall a name.