The three massive stones in the east and north wall of Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard, Cardiganshire. The entrance is to the left of the photo.

The three massive stones in the east and north wall of Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard, Cardiganshire. The entrance is to the left of the photo.

Stones 1, 2, 3 (from left to right in the above photo). Stone 3 (the one which is most likely to be prehistoric) is shown from outside and inside the churchyard. Like many churchyards, the soil on the inside of the wall is much higher, in some places, than that on the outside.

The two stones at the entrance to the churchyard, from inside and outside.

The church from the west. It was built on the edge of a flat plot formed by cutting into sloping ground on which the cemetery extension was cited.

Over 200 years ago some visitors to the church at Ysbyty Cynfyn suggested that it was built within a prehistoric stone circle. This page examines all the many references to the site and concludes that the evidence for such an interpretation is ambigious.

This page includes:

- Introduction

- The church

- Recently discovered references to the stones

- The present remains

- Dolgamfa / Dolygamfa circle of stones

- Temple place name

- The early visitors

- Malkin’s identification of a stone circle

- Comparison with Tregaron churchyard

- Malkin and Iolo Morganwg

- Subsequent Antiquarian visitors

- Churchyards in prehistoric circular sites?

- Stone circles in churchyards

- Standing stones in churchyards

- Stone circles in Ceredigion

- A folly?

- 20th century archaeologist and megalith hunters

- Conclusion

- Arrangement of stones

- Transcriptions of descriptions of Ysbyty Cynfyn in chronological order, 1764-2021

Descriptions of the village of Ysbyty Cynfyn and Parsons Bridge

Ysbyty Cynfyn Inn

Introduction

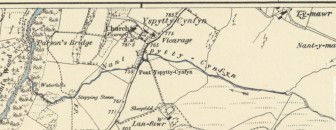

Ysbyty Cynfyn is a settlement with a church now in the community of Cwmrheidol, Ceredigion (SN 752 791).

Aerial photo https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/464252

There are many spellings for Ysbyty Cynfyn. See Iwan Wmffre, The Place-names of Cardiganshire, vol. 3 (2004), pp. 1064-1065 which gives a large number of different spellings of the names from documents dating 1548-1982.

The following are the spellings used by visitors to the site:

Ysbyty Cynfyn

Ysbytty Cenwyn

Sputty-Cen’-wyn

Spythy C’enfaen

Ysbytty C’env’n

Yspytty Cefnfaen

Ysbytty’r Enwyn

Ysbyty Kenvyn

Yspytty Kenwyn

A few early tourists referred to Ysbyty Cynfyn just as Ysbyty which might be confused with Ysbyty Ystwyth, 7 miles to the south.

SUMMARY

The site is well-known because the boundary of the churchyard was thought to incorporate the remains of a prehistoric stone circle. Although it is said that there are many churches in circular grave yards (which were thought by some to have been the sites of prehistoric stone circles or a small defended sites converted into an early Christian grave yards), there are very few established examples. Ysbyty Cynfyn has been cited as an exemplar of such reuse in over 70 manuscript and published sources since about 1800. Despite doubts cast on this interpretation by professional archaeologists since at least 1936, it is still believed to be the site of a stone circle especially by some late 20th century megalith hunters.

The interpretation of Ysbyty Cynfyn now falls into two camps – those who believe, or want to believe that the early Christians constructed a church in a prehistoric religious or ceremonial site; and those who have followed Dr Stephen Briggs whose thorough analysis of the evidence of the history of the site has cast doubt on a prehistoric date for all but one of the standing stones (‘Ysbyty Cynfyn Churchyard Wall’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, (1979), pp. 138-146, available on Welsh Journals on Line). He posited but rejected, the idea that several of the stones might have been erected as a folly in the late 18th or early 19th centuries to attract visitors, but despite his rejection of this possibility, others, having read his paper, repeated it. (e.g. Burl considers it ‘a likely explanation’. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, (1995); (2005), p. 173, no 238.

Some archaeologists have thought that the churchyard is bounded by a prehistoric embankment with standing stones in it. This might have been what is classified as an Embanked Stone Circle. Others think the churchyard boundary (which evidence suggests was never actually circular), is a relatively modern construction.

e.g. review by Frances Lynch of Burl, A., The Stone Circles of the British Isles, (1976). ‘The Druid’s Circle [Penamenmawr, https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/300889%5D is described as an ‘Open Circle’ and Ysbyty Cynfyn as a ‘Circle Henge’, which is strange since both are surely Embanked Stone Circles.’ (Arch. Camb., (1977), p. 154)

It is interesting to note that both the RCAHMW’s web site (Coflein) and the Welsh Archaeological Trusts’ web site (Archwilio), have more than one entry for the site, presenting both possible interpretations.

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/303658/

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/400479/

https://archwilio.org.uk/arch/query/page.php?watprn=DAT5489

https://archwilio.org.uk/arch/query/page.php?watprn=DAT2064

https://archwilio.org.uk/arch/query/page.php?watprn=DAT50163

SEE ALSO https://peaceful-places.com/destination/ysbyty-cynfyn

St John’s Church, Ysbyty Cynfyn

1827

The church was rebuilt

https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/380411

For more on the state of the church and repairs to it see Briggs, (1979), below.

1834-1836

William Ritson Coultart, Architect, surveyed the church at Ysbyty Cynfyn after which the church was reseated and repared with funds from the Incorporated Church Buildings Society, (Society of Antiquaries, London, no. 1756)

Plan of the graves, area A

Plan of the graves, area B

A photograph of every grave stone is also on the same site.

Recently discovered references to the stones

Since the publication of Briggs’ article in 1979, three important manuscripts and one published reference to the site have been discovered. Catcott’s saw a ‘druidical’ stone in 1770; Lipscomb who published an account of his 1799 tour in 1802 saw ‘one large unhewn stone, about seven feet high’ on the site but was unprepared to comment on its significance. Perhaps the most significant are two similar but not identical plans of the site by Iolo Morganwg which are not mentioned in the National Library of Wales’ catalogue of Iolo’s manuscripts. One shows what appears to be six stones forming the periphery of a quadrant of a circle, thought to date to a tour in 1799, the other shows five stones. Iolo almost certainly visited the site in about 1799 / 1800 on his own, and again in 1802 with his friend and fellow antiquary, Walter Davies (who mentioned the stones in his manuscript notes of 1802 and 1813, (details below). Williams, Edward, (Iolo Morganwg), Journey 3 Llandeilo to Cardiganshire and the north, c. 1800, NLW MS 13156A, p. 194, image 200 (details below).

Williams, Edward, (Iolo Morganwg), Journey 3 Llandeilo to Cardiganshire and the north, c. 1800, NLW MS 13156A, p. 194, image 200 (details below).

The suggestion that the graveyard actually had a circular boundary at some time is not supported by any other evidence. John Davies’ map for the Nanteos Estate of 1764 shows the church within a quadrant of a circle; the tithe map of 1845 shows a very similar shape.

The Present Remains

At present there is one large stone in the boundary wall of the churchyard which might have been erected during the Neolithic or Early Bronze Age periods (4,000 – 1,000 BC). The date of four other large upright stones in the boundary is unknown but they might have been added to the boundary at any time since the churchyard was established: two of these are now gateposts. Whether the bank which bounds part of the graveyard is prehistoric or 18th or 19th century remains unknown. The graveyard was doubled in size diring the 20th century.

Dolgamfa / Dolygamfa circle of stones

About ½ mile to the west of Ysbyty Cynfyn church, beyond Parson’s bridge, is a circle of stones on a farm known as Dolgamfa / Dolygamfa. SN 7453 7915. It is one of the finest small Bronze Age cairn-circles in north Ceredigion.

It comprises eleven stones (originally thought to have been twelve stones), about 0.75-1.0m high, mostly leaning outwards, forming an oval, 5.0m NW-SE by 4.0m, within which was a formerly a burial mound, now denuded.

Sansbury, A.R., ‘The Megalithic Monuments of Cardiganshire’, Unpublished B.A. Thesis, Dept. Geography, U.C.W., Aberystwyth, (1932), no. 21, p. 13.

Leighton, David, ‘Structured Round Cairns in West Central Wales, Proceeding of the Prehistoric Society, vol. 50, (1984), no. 20, p. 341, fig. 10, p. 342.

Several tourists made their way from Ysbyty Cynfyn to see Parson’s Bridge but the only person to mention another circle of stones in this area was Meyrick who named it Duffren / Dyfryn Castell. Dyffryn Castell is 2½ miles from Ysbyty Cynfyn, on the A44 close to the junction with the B4343 which leads to Ysbyty Cynfyn but the circle he described is now thought to be Dolgamfa. In the introduction to his County History (1808) Meyrick wrote at some length about druids and stone circles and listed three stone circles in Cardiganshire: Duffren Castell ‘a circle composed at present of eleven stones’; Ystrad Meurig and Alltgoch.

(Meyrick, S.R., The History and Antiquities of the County of Cardigan, (1808), p. lxxxvii )

Under the parish of Llanbadarn Fawr, Meyrick wrote a little more of the Dyffryn Castell site: In a vale called Dyfryn [sic] Castell, is a Druidical circle of stones, which was one of their temples and their court of judicature. (p. 375)

He did not include Ysbyty Cynfyn in his list of stone circles but elsewhere described the four stones there as part of a druidic circle (p. 373). For a little more on Allt Goch, see Meyrick p. 200 but he failed to publish a description of the stone circle of Ystrad Meurig.

If Meyrick’s stone circle of Dyffryn Castell is indeed Dolgamfa, he appears to have been the only one to have noted it for over a century. No reference to the now relatively prominent site of Dolgamfa by any other antiquarian or visitor is known until the 1930s.

Briggs wrote:

By a remarkable coincidence, there survives a kerbed cairn, reserving eleven stones, which is clearly visible by the naked eye from the road between Devil’s Bridge and Dyffryn Castell, and though some distance from the latter, might have been noted down by a traveller under this location in the absence of any more precise detail of his position.

Briggs, C.S., ‘Megalithic and Bronze Age Sites’, Ceredigion, vol. 9, (1982), p. 269

Briggs, C.S., ‘The Bronze Age’ in Davies, J.L., and Kirby, D.P., Cardiganshire County History, vol. 1, (1994), pp. 180, 192

Cook, N., Prehistoric Funerary & Ritual Sites Project Ceredigion 2004-2006 (2006), p. 49

https://archwilio.org.uk/arch/query/page.php?watprn=DAT5624

https://archwilio.org.uk/arch/query/page.php?watprn=DAT2060

‘Temple’ place name

Stone circles were sometimes identified by Iolo Morganwg as Druidic or Gorsedd circles. The farm closest to Ysbyty Cynfyn is called ‘Temple’ (OS Outdoor map, as shown on Coflein, https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/33901/details/temple-lead-mine), as is the lead mine nearby which was being worked in 1887. (https://coflein.gov.uk/media/190/76/mlpc_04_01.pdf)

‘Temple’ was sometimes applied to supposed Druidic sites suggesting that a nearby site had, at some time in the past, been identified with the Druids. However, the name was not included in the very comprehensive list of place names of Ceredigion suggesting that it might be a relatively recent one. (Iwan Wmffre, The Place-names of Cardiganshire, (2004)), but Temple Mine does appear on the Wales Historic Place Names site.

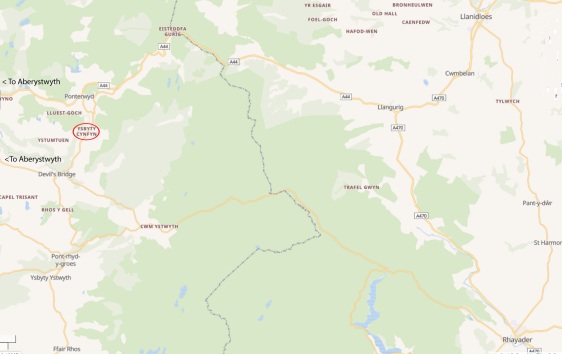

The early visitors

Ysbyty Cynfyn lies on the road between The Devil’s Bridge and Dyffryn Castell (now the A4120). Many early travellers followed the road between Rhayader and Aberystwyth through Cwmystwyth (originally known as Pentre or Pentre Brunant) and the Devil’s Bridge avoiding Ysbyty Cynfyn. When a new road was built from Rhayader along what is now the A44, travellers could take the road between Aberystwyth and Rhayader through Capel Bangor, avoiding the Devil’s Bridge, but if they wanted to see the bridge and Hafod they would have to pass through Ysbyty Cynfyn from the A44 at Dyffryn Castell or Ponterwyd.

Ysbyty Cynfyn lies on the road between The Devil’s Bridge and Dyffryn Castell (now the A4120). Many early travellers followed the road between Rhayader and Aberystwyth through Cwmystwyth (originally known as Pentre or Pentre Brunant) and the Devil’s Bridge avoiding Ysbyty Cynfyn. When a new road was built from Rhayader along what is now the A44, travellers could take the road between Aberystwyth and Rhayader through Capel Bangor, avoiding the Devil’s Bridge, but if they wanted to see the bridge and Hafod they would have to pass through Ysbyty Cynfyn from the A44 at Dyffryn Castell or Ponterwyd.

Most visitors who made the effort to visit Parson’s Bridge would have passed through Ysbyty Cynfyn.

Of the 49 references to Ysbyty Cynfyn before 1900 (fully transcribed below), only 24 mentioned one or more large stones on the boundary of Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard. (See descriptions of Ysbyty Cynfyn and Parson’s Bridge which did not mention the circle.)

Lipscomb saw the stones in 1799 and was the first known tourist to published anything about them in 1802 but had almost nothing to say about them. Mavor (1805) was the first to note that there was more than one large stone but wrote nothing more than ‘in the cemetery … we noticed some ancient pillars’.

Malkin’s identification of a stone circle.

In the first edition of his 1803 tour of South Wales (published in 1804) Malkin noted one ‘upright stone monument’ at the site, but in the second edition (1807) he referred to ‘monuments’ in the pleural and wrote that ‘various writers had fully persuaded [him] that the first British Christians used the Druidical places of worship in the open air, within large circles of stones, and that the church and church-yard of Yspytty Kenwyn may be adduced as an instance of this. The church has been built within a large druidical circle or temple. Many of the large stones forming this circle still remain; and the fence around the church-yard is filled up by stone walling in the intermediate spaces.

There is little to suggest that Malkin revisited Ysbyty Cynfyn between the publication of the two editions of his tour but in the second edition he also added several sentences to his description of Tregaron churchyard, mentioning some inscribed stones, which he does not appear to have learned about from published sources, so it is possible that he had made another visit to the area, or that he had been in correspondence with another antiquary. For example, it is known that Samuel Meyrick visited Tregaron in 1805 and saw the four inscribed stones there. Malkin visited Tregaron during his tours of south Wales in 1803 and although he described the mound on which the church stood as ‘regularly circular’ he made no mention of a stone circle. In the second addition he wrote: ‘In the church-yard are the remains of a druidical circle, with the spaces filled up with stone-walling’, the wording of which is remarkably similar to his description of Ysbyty Cynfyn. This reference to Tregaron was repeated by Abraham Rees in his Cyclopædia, Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature, Volume 36, (1819), ‘Tregaron’. No antiquary or any other visitor, mentioned a stone circle around Tregaron churchyard e.g. Edward Lhuyd, in his additions to Gibson’s edition of Camden’s Britannia (1722) or Fenton (1804); so it seems that Malkin, or his source, was erroneous. (see Tregaron)

Meyrick (1808) was one of the few who described Tregaron churchyard in any detail but he did not mention any possibility of there being a stone circle there. His descriptions and drawings of the inscribed stones show that these could not have been mistaken for a stone circle.

(Meyrick, Samuel, The History and Antiquities of the County of Cardigan, (1808), pp. 246-253)

Malkin’s reference to a possible stone circle at Tregaron convinced several later writers who believed that churches were built within prehistoric circles.

Stones of this nature are seen about other church-yards in this county, as that of Tregaron, &c.; and a huge stone, exactly like that which is always found within a druidical circle, may be seen in the church-yard of Llanwrthwl, in Breconshire, and in many other Welsh church-yards.

(W., E., ‘The Primitive Places of Christian Worship in Wales’, Cambrian Journal, (1858), pp. 204-205)

Haddon wrote: Other churches within circular graveyards occur in Wales. [No examples given.]

(Haddon, A.C., ‘Archaeology and Ethnology’, Transactions of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society, vol. 7, (1930), p. 18)

Johnson noted that large megaliths are also recorded from the churches of Tregaron and Llanwrthwl, in Brecon.

(Johnson, Walter, Byways in British Archaeology, (1912), p. 48 [citing the Cambrian Journal, 1858])

Malkin and Iolo Morganwg

Malkin did not name those who had ‘fully persuaded him’ of the links between Druidical circles and early Christians but the suggestion might have come from discussions with Edward Williams (Iolo Morganwg, 1747-1826). In 1793 Malkin was married at Cowbridge to Charlotte, the daughter of the Rev. Thomas Williams, curate of Cowbridge. Malkin’s ‘The Scenery, Antiquities, and Biography of South Wales’ is based on two journeys during June to October, 1803 when staying at Cowbridge. (see 1st edition, p. 71). Iolo lived at nearby Flemingston (or Flimston; Trefflemin) and had a shop at Cowbridge. Malkin wrote an affectionate portrait of him (Malkin, B.H., The Scenery, Antiquities, and Biography of South Wales, (2nd edition, 1807), vol. 1, pp. 195-204). Surviving letters to and from Iolo to various correspondents show that he and Malkin had mutual friends and there is one surviving letter from Iolo to Malkin but it makes no mention of stone circles (28 November 1809, NLW 21285E, no. 883; Jenkins, Geraint H., et al; The Correspondence of Iolo Morganwg, (2007), vol. 2, letter 817, pp. 879-881).

In addition, Iolo wrote: I have in hand an inscription on a monument in Cowbridge church, for Mr Malkin of No. 7 Grove Place, Hackney, which will detain me only two or three days. (Letter from Iolo Morganwg to Owen Jones (Owain Myfyr), 10 April 1800, BL Add. 15024, ff. 310–11; Jenkins, Geraint H., et al; The Correspondence of Iolo Morganwg, (2007), vol. 2, letter 542, pp. 270) The monument may have been the one in the chancel of Cowbridge church which commemorates Malkin’s wife’s family. Elizabeth Williams had died on 30 July 1798 and the services of Iolo may well have been engaged to add her name to the existing memorial.

Iolo Morganwg was a stone mason, shop keeper, poet, antiquarian, collector, transcriber and faker of Welsh manuscripts. He toured south Wales in about 1800 to gather information for a survey of the state of agriculture. His unpublished notebook includes a small rough plan of the circular graveyard at Ysbyty Cynfyn with the church building in the centre and five dots around quarter of the periphery, presumably representing standing stones.

(Williams, Edward, (Iolo Morganwg), Journey 3 Llandeilo to Cardiganshire and the north, c. 1800, NLW MS 13156A, p. 194, image 200)

This is clearly incorrect since, as Briggs (1979) has shown, there is no evidence that the churchyard was ever even roughly circular.

In 1802 Iolo and Walter Davies appear to have travelled from Davies’ home in Meifod to Cardiganshire on another tour for the same reason. Walter Davies twice referred to Iolo’s identification of the site as a druidical stone circle. The first is in his own notebooks of 1802, when he saw one stone in the churchyard. The second entry appeared in Davies’ notebook for 1813 (details below). This states that Iolo saw ‘the vestiges of an ancient Druidical circle’ at the site. There follows a brief description of five stones but it is not known whether those descriptions came from Iolo or from Davies’s own observation. Davies did not mention the stones in the final published report of 1815.

It is thus possible that there was a circle of stones at the site but Iolo Morganwg was obsessed by what he thought were prehistoric stone circles, which he attributed to the Druids and he invented the ceremonies, still practiced by the Gorsedd of Bards at Eisteddfodau, which incorporate circles of stones. (Cathryn A Charnell-White, Bardic Circles: National, Regional and Personal Identity in the Bardic Vision of Iolo Morganwg, (2007). There is almost nothing about stone circles in any of Iolo’s surviving correspondence (Geraint H Jenkins, et al., The Correspondence of Iolo Morganwg, 3 vols, (2007).

The association of stone circles with the druids dates back to the 16th century and is sometimes referred to as Druidomania. It is worth noting that Iolo did not use the term ‘Druidic’ in his note book with the plan of the stones in Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard of about 1800 but simply stated: Church in an ancient circle, but Catcott (1770) and everyone who visited the site after 1800, including Walter Davies, Iolo’s companion on the tour in 1802, applied ‘Druidic’ to the site.

In a letter mostly on the meaning and origin of a few Welsh words, Iolo Morganwg wrote:

The Welsh word for church is ‘llán’ and literally signifies a circle acquainting us with its druidic origin.

(Letter from Iolo Morganwg to John Nicholas, [?1792], Jenkins, Geraint H., et al; The Correspondence of Iolo Morganwg, (2007), vol. 1, p. 455, letter 183)

There is nothing in Iolo’s notebooks [or elsewhere] about the use of stone circles as sites of subsequent Christian worship. He might not have thought it right for the religion of the Church in Rome to be associated with his perception of the rational religion of the Druids.

(Mee, Jon, ‘‘Images of Truth New Born’: Iolo, William Blake and the Literary Radicalism of the 1790s’ in Geraint H. Jenkins, (ed.) A Rattleskull Genius. The Many Faces of Iolo Morganwg, (2005), pp. 190-191)

Iolo believed that Druidism had something in common with Christianity and accepted that Druids and Bards held ceremonies in stone circles but he did not link stone circles with early Christian sites.

(NLW ms 13144A, pp. 242-244) transcribed in Charnell-White, Cathryn, Bardic Circles …, (2007), p. 168)

It was Iolo’s fervent imagination which linked ancient stone circles with those he and his followers created for the Gorsedd of Bards from 1792 (although the early examples comprised just a few stones, sometimes small enough to fit into a pocket, such as those laid out in the grounds of the Ivy Bush inn, Carmarthen in 1819 for the first Eisteddfod which incorporated Gorsedd ceremonies. Other than the double circle and sinuous line of stones constructed in about 1849 around the rocking stone at Pontypridd, very few permanent circles were constructed for the Gorsedd until 1897). Although laudanum might have influenced Iolo’s interpretation that five stones on the site formed a quarter of a circle, it would not have had the same effect on a more sober Walter Davies who wrote a brief description of all five stones in his note book, possibly based on Iolo’s notes.

Subsequent antiquarian visitors

Samuel Meyrick in his The History and Antiquities of the County of Cardigan, (1808, 1810), noted that there were four stones in the churchyard at Ysbyty Cynfyn ‘placed as to form the quarter of the circumference of a circle’ which he thought ‘in all probability, a druidical circle’. He recorded the size of the largest and stated that two were now gate posts and that others had probably been incorporated in the structure of the church.

In 1808, the antiquaries Richard Fenton and Sir Richard Colt Hoare passed through Devil’s Bridge and saw Thomas Johnes’ mansion at Hafod undergoing rebuilding after the fire but only Colt Hoare mentioned the stones at Ysbyty Cynfyn in his journal. However, Fenton, in his Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire (1810), discussed the adoption of prehistoric sites by Christians and ended his brief paragraph on the subject with: ‘There is in Cardiganshire a church built in the centre of a druidical circle’. He did not name the church but only Ysbyty Cynfyn falls into this category in the county.

Colt Hoare was aware of Iolo’s unpublished ideas about stone circles and Bards, through their mutual friend William Owen Pugh.

(Colt Hoare, Richard, The Itinerary of Bishop Baldwin through Wales, (1806), vol. 2, pp. 317-318; Suggett, Richard, ‘Iolo Morganwg: Stonecutter, Builder and Antiquary’, in Geraint H. Jenkins, (ed.) A Rattleskull Genius. The Many Faces of Iolo Morganwg, (2005), pp. 225-226)

Churchyards in prehistoric circular sites?

Some visitors believed that Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard was constructed within a prehistoric site because it was thought that the boundary was roughly circular and there are some large standing stones on its boundary. Although it is claimed that many churches in Wales were built within prehistoric ceremonial sites firm evidence is absent or ambiguous. For example, Sir Norman Lockyer, in his work on Stonehenge, asserted that many churches had been built on the sites of circles and menhirs, but he proffered no actual examples. (Stonehenge, (1906), p. 219). In the 2nd edition of his Stonehenge (1909), he devoted a whole chapter to the origins and plans of Gorsedd circles.

Several of the 20th century references to Ysbyty Cynfyn (below) assume that because the churchyard wall was circular (even though it was not), it must originally have been Druidic.

According to Fleure, the late G. G. T. Treherne listed a large number of churchyards in Carmarthenshire which either had or seem to have been enclosed by stone circles. (Fleure, H.J., ‘Problems of Welsh archaeology, A Lecture Given by Request at the Liverpool Meeting of The British Association for the Advancement of Science, September, 1923’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, (1923), pp. 235-236. George Gilbert Treherne was the first president of the Carmarthenshire Antiquarian Society: his list of churchyards in Carmarthenshire has not been found.)

The origin of the circular plan of some churchyards, found particularly in Wales, has rarely been demonstrated.

Possible origins are that they were constructed within:

- a prehistoric stone circle or henge

- a Bardic or Druidic gorsedd circle (discounted because such structures are really based on 17th and 18th century antiquarians and on Iolo Morganwg’s fertile imagination.

- a late Iron Age or possibly early post Roman defended settlement sites [possibly e.g. Y Gaer, Bavill, north Pembrokeshire. ].

- a llan – a circular enclosure, initially used as early Christian cemetery which might later have had a church built within it. Y Gaer, Bavill, may again be an example of this. In Wales, Llan often the first syllable of a settlement or parish name followed by a saint’s name.

There may well have been topographical or pragmatic reasons for enclosing a churchyard in a circular boundary.

It is possible, as some have suggested, that stones set up in prehistoric times, whether singularly, in rows or circles, were removed (for superstitions reasons) or broken up for reuse in building of the church or churchyard wall.

A few examples of curvilinear churchyard boundaries in Wales:

Llangeitho (Ceredigion)

Gwnnws (Ceredigion)

Llanddewi Brefi (Ceredigion)

St Teilo, Maenclochog, (Pembrokeshire). A very likely early mediaeval site close to a prehistoric site.

St Edrins, (Pembrokeshire) A site which produced five early medieval carved stones dated 9th to 11th century.

Llanelltyd, Merionethshire Ellis, T.P., The Story of Two Parishes, Dolgelley and Llanelltyd, (1928). The author suggested that the churchyard was laid out to be a circle enclosing an acre with the centre being the altar (see below for details).

St Llwchaiarn’s Church, Llanmerewig The building is sited in a raised circular churchyard which has been claimed as a prehistoric enclosure.

There is a row of four stones at St Winifred’s churchyard, Gwytherin, Llangernyw, Denbighshire. One of them has an inscription probably 5th-6th century AD., but the date of their erection is unknown. There is a near-by Bronze Age burial mound. The yew trees in St Winifred’s churchyard are thought to be 2,500-3,000 years old.

Suggestions that churches were built on circular sites:

1837

The Christian Churches in this kingdom were founded either on the sites of Druidic Temples (Llannau – and the ancient term Llan is prefixed to such), or contiguous to them. Llanilid and Llangewydd, in Glamorganshire, among many others, are corroborative instances. At Llanilid the old Druidic oratory (Gwyddfa) still remains, nearly perfect; reverently spared by Papists and Protestants … not a vestage of the old church at Llangewydd remains, except the boundaries of the churchyard, appearing higher than the rest of the field (still called Cae’r Hen Eglwys), may be traced … but two large stones, apparently the remains of a cromlech, prior to Christianity, yet stand there.

Williams, Taliesin, The Doom of Colyn Dolphyn, (London: 1837), p. 107

1886

The paragraph above by Taliesin Williams [son of Edward Williams, Iolo Morganwg), The Doom of Colyn Dolphyn, (London: 1837), was quoted and followed by:

Similar remains [two upright stones] at present stand in Llangernyw churchyard. … If they [churchyards] are found to be circular or ovoidal, then most probably, the round churchyards, which are quite common in Wales, were sacred spots in the days of our Celtic forefathers …

Elias Owen, Stone Crosses of the Vale of Clwyd, (1886), pp. 122-123

1896

The most ancient churches in Wales have circular or ovoidal churchyards – a form essentially Celtic – and it may well be that these sacred spots were dedicated to religious purposes in pagan times, and were appropriated by early Christians, – not, perhaps, without opposition on the part of the adherents of the old faith – and consecrated to the use of the Christian religion. In these churchyards were often to be found holy, or sacred wells, and many of them still exist, and modes of divination were practices at these wells, …

Owen, Elias, (Rev.), Welsh Folk-lore, A collection of the folk-tales and legends of north Wales; being the prize essay of the national Eisteddfod, 1887, revised and enlarged by the author, (1896), pp. 160-161

1928

Llanelltyd church stands in the middle of a circular graveyard, one of the most perfect specimens of the type left to us. The two modern additions … have fortunately left the old grave-yard untouched, and it is hoped that [it will never be altered]. It is one of the most precious historical remains in Merioneth. This circular graveyard has lasted well over a thousand years; probably 1300 years. …

The reason why it is circular is this. In olden times the altar in a church was a very holy place indeed. … anyone who claimed the protection of the altar, no matter what he had done, could not be touched. … and round the sacred altar a circle was drawn, within which a man … could claim sanctuary for seven years and seven days. … the limits of the circle were settled in this way.

A ploughman stood at the foot of the altar, with his arms outstretched, and, in his outstretched hands, he held the yoke of his plough team. A plough team consisted of eight oxen, yoked two abreast, and the yoke extended from the front of the first couple to the end of the plough. Holding the yoke in his hand, the ploughman … swept it round in a circle, and all land within that circle, which was called the “erw” became holy ground. That was the origin of the phrase “God’s acre” for “erw” means “acre”. It was the immediate circle of God’s protection, not of the dead, but of the living, however guilty.

Some people, I think rather fancifully, go a great deal further back than that in explaining the old Welsh circular graveyards. They associate them with the ancient stone-circles of the Druids, or whoever it was who made stone circles.

[A yoke is normally the term applied to the length of wood, with two curves in it which fitted over the necks of the animals – but it seems that Ellis is referring to a rein of some sort attached to the wooden yoke and controlled by the ploughman. In order for the circle to encompass an acre, the rein would have to be 39.242 yards long = 117.326 feet which must be more than double the length of four oxen and the plough. The circle would have to be marked out with the altar in place but before the church was built.]

Ellis, T.P., The Story of Two Parishes, Dolgelley and Llanelltyd, (1928), pp. 53-55

1936

The late J.P. Rees, Parish Clerk held this view [that Tregaron church stands on a ’round coppe of cast yearth’ as Leland put it (above)] as well as the tradition that the sacred enclosure was formerly a Druidical circle. We know it was a common practice to build Christain Church [sic] on the sites of Pagan Temples, e.g. the churches of Ysbyty Cynfyn and Gwnnws (Ceredigion).

Rees, D.C. (Rev.), Tregaron, Historical and Antiquarian, (1936), pp. 19-21

Stone Circles in Churchyards

A very few churches can be shown to have been built within a circular prehistoric site.

Knowlton, Dorset – a church built within a henge

Midmar, Aberdeenshire (Bronze Age circle within the churchyard, the church was built near the circle in 1787.)

Ysbyty Cynfyn, appears to be the only site in Britain where up to five large standing stones were incorporated into the churchyard boundary and it has been used as an exemplar of the reuse of a prehistoric ceremonial site by the early Christian church, despite doubts cast on the date of erection of most of them.

Standing stones in churchyards

A few churchyards in Britain contain what appear to be prehistoric standing stones but it is not known whether they were standing before the church was built or were moved there subsequently (as is thought to have occurred with some early Christian crosses and inscribed stones).

ENGLAND

All Saints’, Rudston, East Yorks (the tallest standing stone in England).

St Mary’s, Bungay, Suffolk – The Druid’s Stone (glacial erratic?).

St Levan’s, Cornwall

St Mabyn, Cornwall: The ‘Longstone’ broken up and taken away for superstitious reasons.

WALES

St Gwrthwl’s, Llanwrthwl, Powys (Archwilio web site)

1.75 m high stone, possibly originally higher, thought to be prehistoric.

A huge stone, exactly like that which is always found within a druidical circle, may be seen in the church-yard of Llanwrthwl, in Breconshire, and in many other Welsh church-yards.

(W., E., ‘The Primitive Places of Christian Worship in Wales’, Cambrian Journal, (1858), pp. 204-205)

St Twrog’s, Maentwrog (Archwilio web site)

The stone of Twrog, a small rounded standing stone, was erected to the west of the south porch. This stone gave the parish its name and features in the fourth branch of the Mabinogi.

Llandysiliogogo

At Llandysiliogogo in south Cardiganshire a large menhir lies beneath the church pulpit.

George Eyre Evans, newspaper, 17.9.1903, renovations 1890. Pulpit rested on a huge unhewn stone, so large that it could not be moved, so was buried. The newspaper articles were incorporated in GEE Cardiganshire: a personal survey …; GEE, Cardiganshire, its plate, … Arch Camb, vol. 18, (1918), pp. 323-339. There is nothing about this in GEE’s note books and the Parish minutes are missing.

Bowen, E.G., ‘The Human Geography of West Wales’, in W Ll. Davies (ed), N.U.T. Conference, Aberystwyth Souvenir, (1933), p. 15

Bowen, E.G., `Menhir in Llandysiliogogo Church, Cardiganshire’, Antiquity, vol. 54, (1971), pp. 213-215

A large stone was found lying beneath the pulpit during 19th century restoration has been accepted as a genuine neolithic/bronze age standing stone, and a further large stone is reported to have been present within the churchyard.

Johnson devoted two whole chapters to churches on pagan sites, but other than Ysbyty Cynfyn, he was unable to cite further examples of churches within stone circles in Wales.

(Johnson, Walter, Byways in British Archaeology, (1912), p. 48)

Leslie Grinsell listed a number of churches which he believed were associated with prehistoric sites:

Knowlton, (Dorset) church in henge

Stanton Drew (Somerset) almost adjoins the Cove of 3 stone circles and avenues

Taplow (Bucks) adjoins a Saxon barrow

Ogbourne St Andrew (Wilts) Bronze Age round barrow in the churchyard

Berwick (East Sussex) ?Saxon barrow in the churchyard

Church Hill, Brighton near Bronze Age barrows

Ludlow (Shropshire) barrow in churchyard

Fimber (Humberside) church built on probable Bronze Age barrow

Rudston (Humberside), standing stone in churchyard near the intersection of four ?Neolithic cursuses

In Wales the best known instance is the church at Ysbyty Cynfyn, a rebuilt ?mediaeval building standing within a setting of standing stones, whose status as a stone circle is very doubtful (Burl, 1976, pp. 259-260; Briggs, 1979)

St Tysilio, Llandysiliogogo Menhir beneath the altar (Bowen, 1971)

Midmar (Aberdeenshire), stone circle in graveyard

Dunino (Fife), church incorporates stones from a stone circle (Grinsell, (1976), p. 218

Some standing stones named after saints (e.g. Samson)

Crosses inscribed into or set up on prehistoric sites.

(Grinsell, Leslie, ‘The Christianisation of prehistoric and other Pagan sites’, Landscape History, vol. 8, (1986), pp. 27-37)

Stone Circles in Ceredigion

Only two certain stone circles have been identified in Ceredigion.

Bryn y Gorlan

A semi-circle of ten visible stones, diameter about 18m

Moel y Llyn

Two circles – full antiquarian’s descriptions on this site.

A Folly?

The accounts published by visitors to Ysbyty Cynfyn before 1805 mentioned only one stone, so the reference to as many as five by later writers might support Briggs’ suggestion that other stones were introduced to the site around 1800 as a folly, in the form of an incomplete circle of stones, at the end of the 18th century or the beginning of the 19th, either by the land owner (the Powell’s of Nanteos), or by the parish when improving the churchyard boundary, but he dismissed both options as very unlikely.

He also rightly asserted that a number of tourists who visited Ysbyty Cynfyn made no mention of any stones on the site but this does not mean that there were none – a sufficient number of reliable antiquaries mentioned the presence of more than one large stone on the site but they did not agree on the number: Mavor (published 1805) refers to some ancient pillars, but unlike most of the others who visited the site, did not ascribe them to the Druids; Colt Hoare (manuscript 1808) mentioned three Druidical stones and Meyrick (published 1808) identified four which he thought were probably Druidical. Generally, most tourists’ publications followed what their predecessors had published and since only one stone was mentioned in print until 1805, earlier visitors to the site may not have mentioned them simply because they were not looking for them, or, as Lipscomb wrote about the single stone he saw in 1799 ‘as I could not obtain any account of it, I cannot convey any information about it’.

However, there is nothing whatever to suggest that a few large stones were added to the site around 1800 but equally nothing to explain the presence of the two massive gate posts to the graveyard and one other large upright stone (in addition to the largest standing stone which is generally considered to be prehistoric.)

20th century archaeologists and Megalith hunters

The large upright stones in Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard wall were not mentioned at all in Archaeologia Cambrensis (first published in 1846) until Fleure’s article of 1924.

By the beginning of the 20th century, archaeologists, geographers, and those who hunted for megaliths and sacred or mysterious sites fell into two camps – those who accepted that the church had been built inside a prehistoric stone circle (citing it as an exemplar of such) and those who thought that the evidence for a circle was insufficient. A few, including Grimes, changed his mind, from doubting that it was a stone circle (1936) to suggesting that it was an embanked circle (1963).

Some of the descriptions of the site are clearly derived from earlier published sources but the (mis)interpretation becomes more confident. The enthusiastic local antiquarian, George Eyre Evans (1903) wrote that the stones at Ysbyty Cynfyn were ‘doubtless, part of a Druidical circle’ and thought that similar stones had been broken to pieces to build the church.

C. Evans (1911) was convinced that there should have been 12 stones there (this was the number of stones erected at many Gorsedd circles where proclamation and other ceremonies were held for Eisteddfodau after 1897).

H.J. Fleure (1877-1969, Professor of Anthropology and Geography, Aberystwyth, 1917-1930) and E.G. Bowen (1900-1983, Gregynog Professor of Geography and Anthropology, Aberystwyth 1946-1968) both wrote about the site several times between 1923 and 1936. They suggested that the church had been built in a prehistoric circle, indicating continuity of the use of a sacred site but like most other writers on the subject they did not cite parallels, although Fleure mentioned G.G.T. Treherne’s (unpublished) list of a large number of churchyards in Carmarthenshire which had links with stone circles. Bowen (1936) suggested that stone circles had acquired ‘mysterious and magical powers’ long after their original purpose was forgotten which led to many popular theories about their significance.

Such confidence was not so much founded on firm evidence but on a myth, the repetition of which gave apparent credence to the theory.

Bowen, however, began to have reservations. He discussed the stones during a visit to the site by the Cambrian Archaeological Association in 1946 and cast doubt on the interpretation of the site as a former stone circle, possibly following Grimes (1936), who then revised his view in 1963. The anonymous author of a report of the discussion during the Cambrians’ visit in 1946 wrote the following:

Unfortunately, however, it can be shown on detailed examination that one at least of the stones has been inserted into the wall rather than the wall built around the stone. Consequently, the Association on its recent visit felt that it could not readily accept the tempting conclusions of the earlier archaeologists.

As late as 1972, the renowned archaeologist, Glyn Daniel believed that the ‘Present-day opinion inclines to the opinion that it is the remains of a genuine stone circle’, a conclusion with which A.J. Bird concurred in his Re-Assessment of menhirs in Cardiganshire published in the same year.

Many of the late 20th and early 21st century reports by professional archaeologists are, quite rightly, ambivalent or present a minimal interpretation, based on the fact that only the largest stone could be earlier than the churchyard wall: many of those who wrote after Brigg’s 1979 paper agreed with his conclusions.

However, most of those who studied and compiled lists of stone circles preferred to describe it as the remains of a circle. These include some respected archaeologists; those who followed Professor Alexander Thom’s now largely dismissed theories of the 1960s and ‘70s that stone circles were laid out using a standard unit of length (the ‘Megalithic yard’) aligning them and related stones to significant astronomical events (see Bird, 1971, below) and the ‘New Age’ Megalith Hunters and others who seem to ignore the evidence and firmly accept the suggestion that a church was deliberately built within the site of a prehistoric stone circle. As Gregory wrote in the 2015 edition of his book (below): There are no ifs or buts about Ysbyty Cynfyn, which provides an impressive example of the continuity of religious association in a burial ground.

A parallel to these fluctuating changes in interpretation may be found at the site Bryn Gwyn, near Brynsiencyn, Anglesey where three uprights and the stump of a fourth were identified as the remains of a circle in 1723. Subsequently several antiquarians agreed with this interpretation but as the remaining stones reduced in number, leaving only two by the beginning of the 20th century, archaeologists doubted that the site had been a circle. However, excavations in 2010 found that there had been 8 stones forming a circle, 16m diameter. (Smith, G., The Bryn Gwyn Stone Circle, Brynsiencyn, Anglesey, (Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, 2013)

Conclusion

It is generally agreed that the largest of the upright stones at Ysbyty Cynfyn is likely to be prehistoric. The four other large stones might have formed part of a stone circle but they appear to be contemporary with or later than the churchyard bank. The variation in the number of reported stones can be attributed to the probability that the earlier visitors ignored some of the stones (as has been shown, many of the visitors to the site made no mention of any of the standing stones).

The suggestion that a prehistoric stone circle at this particular site was adopted as a site of Christian Worship, first published by Malkin in 1807, might have been instigated by discussions with Iolo Morganwg who was obsessed with stone circles. The evidence strongly suggests that later writers were very fond of this theory but their partiality for such an idea overrode the lack of firm evidence for it.

The problem with this site, as with others where firm evidence is lacking, is that the interpretation of the site as an exemplar of the use of a prehistoric ceremonial site by early Christians has been repeated so often, and by many, including respected academics, that what is almost certainly a myth is now very difficult to dispel. The correct interpretation will be found only by archaeological excavation, which would almost certainly be restricted to the original boundary of the churchyard because graves will have destroyed much of the evidence of prehistoric activity that lay within it, but perhaps a thorough geophysical survey might provide some more clues, especially along the line of the old north boundary where there are few graves.

List of references to Ysbyty Cynfyn village, church and /or Parson’s Bridge including those who did not mention the circle. Published descriptions of the stones are marked in bold. Full transcriptions below.

Of the 49 references to these sites before 1900, only 24 mentioned one or more large stones on the boundary of Ysbyty Cynfyn churchyard.

| Year | Number of | Size | ‘Druidical’ | Author |

| stones noted: | (published unless otherwise stated) | |||

| 1757 | no mention | Lewis Morris | ||

| 1764 | no mention | Estate map | ||

| 1769 | no mention | Grimston, unpublished | ||

| 1770 | 1 stone | Druidical | Catcott, unpublished | |

| 1784 | no mention | Cumberland, unpublished | ||

| 1787 | no mention | Hutton, published 1891 | ||

| 1789 | no mention | Skrine | ||

| 1794 | no mention | Cumberland | ||

| 1797 | no mention | Manners | ||

| 1799 | 1 stone | 7ft | Lipscomb | |

| 1799 | no mention | Plumptre, unpublished | ||

| [1799] | 6 stones | ancient circle | Iolo Morganwg plan, unpublished | |

| [1800] | 5 stones | ancient circle | Iolo Morganwg plan, unpublished | |

| 1802 | 1 stone | large | Druidical | Davies citing Iolo, unpublished |

| 1803 | 1 stone | large | Druidical | Malkin |

| 1803 | no mention | Shepherd | ||

| 1805 | some ancient pillars | Mavor | ||

| 1807 | many large stones | Druidical | Malkin, 2nd edition | |

| 1808 | 3 stones | Druidical | Colt Hoare | |

| 1808 | 4 stones | 11 x 5’6” x 2 ft | Druidical | Meyrick |

| It is likely that all the following descriptions were based on earlier publications and not on first-hand observation. | ||||

| 1808 | ancient pillars | Nicholson (?based on Lipscomb) | ||

| 1810 | 4 stones | up to 11 x 6ft | Druidical | Rees (based on Meyrick) |

| 1810 | no mention | Hue | ||

| 1810? | no mention | Boughton | ||

| 1811 | circle | Druidical | Fenton | |

| 1813 | 5 stones | 7 ft | Druidical | Davies notes based on Iolo Morganwg, [1800] |

| 1813 | 1 stone | Nicholson 1 (based on Lipscomb) | ||

| 1813 | 4 stones | 11 x 5’6” x 2ft | Druidical | Nicholson 2 (based on Meyrick) |

| 1813 | 4 stones | 11 x 5+ x 2ft | Druidical | Wood, J.G. (?based on Meyrick) |

| 1819 | no mention | Faraday | ||

| 1821 | no mention | Newell | ||

| 1823 | many | Druidical | Freeman (based on Malkin) | |

| 1823 | 4 stones | Druidical | Pinnock, directory | |

| 1824 | no mention | Martineau | ||

| 1825 | no mention | Batty | ||

| 1831 | several | Druidical | Leigh guide book | |

| 1833 | no mention | Anon of Hull | ||

| 1833 | 4 stones | Druidical | Lewis, Topographical Dictionary | |

| 1835 | no mention | Anon, Penny magazine | ||

| 1836 | no mention | Robinson | ||

| 1837 | no mention | Horace | ||

| 1838 | many | Druidical | Bingley, 3rd edition, based on Malkin or Freeman | |

| 1840 | 4 stones | 11’ x 5’6” | Druidical | Nicholson, 3rd edition |

| 1841 | no mention | Anon, Welsh Journal | ||

| 1844 | no mention | Anon, Account of a tour | ||

| 1848 | 4 stones | Druidical | Morgan, (derived from Meyrick 1808, or Nicholson’s guide) | |

| 1852 | several | Druidical | Black, Guide book | |

| 1852 | 4 stones | Druidical | Yr Haul | |

| 1854 | no mention | Borrow | ||

| 1854 | no mention | Bourne | ||

| 1858 | at least 3 | very large | Druidical | E.W. |

| 1861 | 3 stones | Druidical | Murray’s handbook | |

| 1866 | 4 stones | Druidical | Rowlands (Partly based on Rees, 1810) | |

| 1868 | 4 blocks | Druidical | National Gazetteer | |

| 1878 | no mention | Groves | ||

| 1880 | mention | Druidical | Curtis (based on Malkin) | |

| Most of the following were written by professional archaeologists, geographers or megalith hunters, most of whom visited the site. | ||||

| Year | Number of | Size | Author (published unless otherwise stated) | |

| stones noted: | ||||

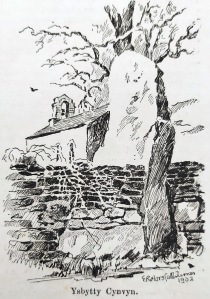

| 1902 | some | huge | Horsfall-Turner | |

| 1903 | some | George Eyre Evans | ||

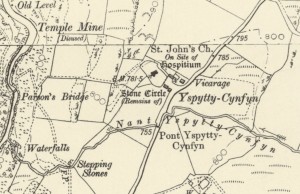

| 1905 | Stone Circle, (Remains of) | Ordnance Survey map | ||

| 1911 | 4 or 5 stones | Evans, C | ||

| 1911 | huge monolith from a circle | Green | ||

| 1923 | circle in part | Fleure | ||

| 1924 | ruined stone circle | Fleure | ||

| 1929 | church within the circle | Peak and Fleure | ||

| 1930 | most stones still standing | Haddon | ||

| 1930 | several (3-5) | immense | Allcroft | |

| 1931 | stone circle | Peake and Fleure | ||

| 1933 | some of a megalithic circle | Bowen | ||

| 1936 | stone circle | Bowen | ||

| 1936 | rejected circle | Grimes | ||

| 1946 | rejected circle | Cambrian Archaeological Association | ||

| 1948 | standing stones | Ordnance Survey map (demoted from ‘Stone Circle, remains of’) | ||

| 1952 | 5 stones | Kendall | ||

| 1954 | ancient stones | Gossiping Guide | ||

| 1963 | reinstated (earth work) | Grimes | ||

| 1972 | 3 in megalithic circle | Daniel | ||

| 1972 | megalithic circle | Bird (following Daniel) | ||

| 1976 | 1 stone from a circle | Burl | ||

| 1979 | unlikely circle; | Briggs | ||

| 1979 | claimed megalithic circle | Bowen | ||

| 1982 | 1 standing stone? | Briggs | ||

| 1984 | embanked stone circle | Williams | ||

| 1993 | significant stones | Evans | ||

| 1994 | 5 stones | John | ||

| 1994 | unlikely circle | Holder, citing Briggs, 1979 | ||

| 1994 | no mention till late 18th | Briggs | ||

| 1994 | church in circle | Lord | ||

| 1995 | 5 stones | Burl, based on Briggs, 1979 | ||

| 1997 | 3 stones | Hayman | ||

| 1997 | 1 (of an alignment) | Sambrook | ||

| 2002 | monolith | Archwilio | ||

| 2003 | uncertain | Sambrook | ||

| 2005 | monolith? | Cook | ||

| 2018 | not listed | Burnham | ||

Arrangement of stones

These are the full descriptions of the stones and their settings from all those who appear to have visited the site (citations below).

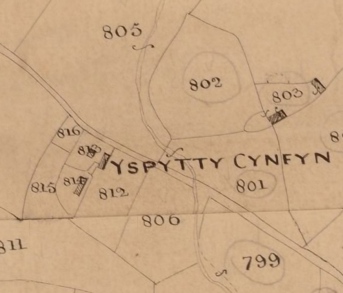

1764 Map

no stones but curved boundary is about 40m diameter

1799 Lipscomb

One large unhewn stone, about seven feet high, was placed on the north-side of the churchyard

1799? Iolo

Plan with 6 stones

c. 1800 Iolo

Plan with 5 stones, with gateway between the two eastern ones

1802 Davies

A large stone pitched on end in the eastern fence of the churchyard

1803 Malkin

a large, upright stone monument, with the [inscribed] characters entirely defaced

1805 Mavor

some ancient pillars

1807 Malkin

large, upright stone monuments, with the characters entirely defaced. … Many of the large stones forming this circle still remain; and the fence around the church-yard is filled up by stone walling in the intermediate spaces.

1808 Meyrick

four stones so placed as to form the quarter of the circumference of a circle. The largest of these is that standing to the east, and measures about 11 feet above ground, five feet six inches in breadth, and about two feet thick. Two of the others form at present the gate posts, and stand to the southward.

1808 Nicholson

some ancient pillars

1808 Colt Hoare

Three stones

Transcriptions of descriptions of Ysbyty Cynfyn in chronological order.

The date at the head of each transcription is the date of the visit, if known, or date of publication.

1757

Lewis Morris (1701-1765) who lived in Ceredigion for many years spent 40 years compiling a list of many Welsh place names with explanations. He included Ysbyty Cynfyn under other places prefaced with Ysbyty, but had nothing else to say about the site.

Yspytty Ieuan. There are several places of this name, where the hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem resided, the Church of Rome’s militia. In the deanery of Rhos, in Denbighshire, a church and parish. Yspytty Cynwyn; Yspytty ar Ystwyth; Yspytty Ystrad Meurig. Vulgo Spitty.

Morris, Lewis, ‘Celtic Remains, or the ancient Celtic Empire described in the English tongue, etc.’, British Library, Add MS 14910-14911

A transcript of Lewis Morris’s ‘Celtic Remains’ made in 1778-1779 by his nephew Richard Morris, NLW MS 1735D, p. 465 (correctly 565)

Evans, D Silvan, (ed.), Celtic Remains by Lewis Morris, (Cambrian Archaeological Association, 1878), p. 438

1764

A map of part of the estate of Nanteos shows that the radius of the curved boundary is about 2 chains = 44 yards = about 40 m.

Map of Ty Mawr, mark’d X and occupy’d by Wm. Lewis, Yskir Wonion, mark’d + and occupy’d by Morgan Evan under tenant to Wm. Lewis + Spyty Cenfin, mark’d ө & occupy’d by Jno. Edward, all in the parish of Llanbadarn Fawr.

Surveyed by John Davies, Estate surveyor.

Scale [1:3,960]. 1 in. = 5 chains. 1764

NLW, Nanteos 316

1770

In the churchyard [at Ysbyty Cynfyn] a druidical stone: not placed as a fence since it stands edgeways to the bounds.

Diaries of Tours made in England and Wales by the Rev. A Catcott (1748-1774), Bristol Central Library, B6495, p. 18

[The Reverend Alexander Catcott (1725–1779) was an English geologist and theologian born in Bristol. As with his tour of Wales in 1756 his journal contains almost nothing but descriptions of the surface geology which he was gathering to prove his belief in the biblical flood.]

1799

We left the Hafod Arms [inn at Devil’s Bridge] … with a desire to enjoy, from the top of Plinlimon, the prospect of the setting sun… We entered on a road enclosed between two hedges. … Passed a little church, which seemed to be without bells, there being an empty cupola on the roof, which was destitute of a tower. One large unhewn stone, about seven feet high, was placed on the north-side of the churchyard but as I could not obtain any account of it, I cannot convey any information about it.

Lipscomb, George, Journey into South Wales…in the year 1799, (London, 1802), p. 141

1799?

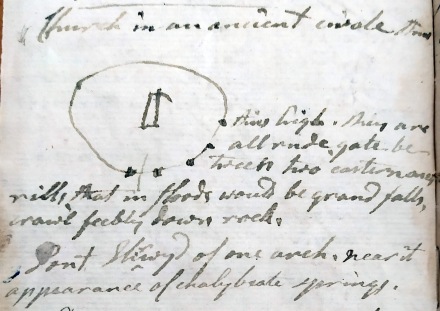

There are two plans drawn by Edward Williams (Iolo Morganwg) of what appears to be Ysbyty Cynfyn church yard, the first showing six dots, presumably representing stones; the other five. Some of the wording on the same page as the two plans is very similar, suggesting that one is an (inaccuarate) copy of the other.

(For the alignment of this sketch plan, see the other plan, below)

(For the alignment of this sketch plan, see the other plan, below)

A plan of a circle with six stones appears on the back of an undated letter drafted by Iolo Morganwg. The first few words under the drawing are probably Pont Herwydd one arch … [Ponterwyd a settlement just over a mile to the north of Ysbyty Cynfyn.]

Elsewhere on the sheet is the following:

Large rude stone N.E. ch. yd [word almost rubbed away] between two very large [word almost rubbed away ?stones] – Devils for ?cherubins

The last phrase might be from Shakespeare’s, Troilus and Cressida, Act 3, scene 2: ‘Fears make Devils of Cherubins; they never see truly’; alternatively: ‘Fears make Devils Cherubins’.

To the right of the plan is the following which is very similar to that by the other plan (below):

rills crawl down rock bis? ?[but] ?would be noble ?cataracts in flood. [Iolo used the word ‘rills’ many times for small streams]

Although the note book does not mention Ysbyty Cynfyn, it lists Devil’s Bridge and Hafod as two of the places Iolo Morganwg passed through between Aberystwyth and Rhayader. The draft letter relates to visiting the homes of those who had old documents worth copying – the task Iolo was commissioned to do for Owen Jones (Owen Myfyr) in 1799 and 1800. It seems likely that this note and plan dates to 1799.

‘Tour in Wales 1799 by E.W. / North Wales Itinerary 1799’, NLW Iolo Morganwg, E5/18 (viii), loose sheet.

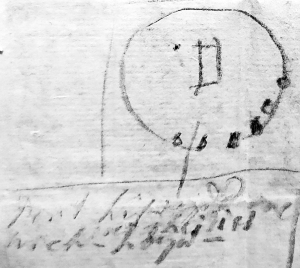

1800 (about)

[The largest stone (next to the words ‘this high’ is now to the north-east of the east end of the church but this appears to show the church wrongly aligned, especially if the entrance to the grave yard is between the two stones to the left (where the circle is cut by a vertical line).

[The largest stone (next to the words ‘this high’ is now to the north-east of the east end of the church but this appears to show the church wrongly aligned, especially if the entrance to the grave yard is between the two stones to the left (where the circle is cut by a vertical line).

A very similar plan of [Ysbyty Cynfyn] showing a circular churchyard with the church in the centre and five dots, probably representing standing stones on the periphery. The two squarish dots at the bottom of the sketch might be the cemetery gate posts.

Walk over Hafod grounds with E & B, visit Parsons Bridge,

Church in an ancient circle stone

?this high [i.e. ?the stone nearest ‘this’ is the highest], they are

all rude, gate be

tween two eastern ones

rills that in floods would be grand falls crawl feebly down rocks.

Pont ?Stirwyd [Erwyd] of one arch, near it

appearance of chalybeate springs.

Williams, Edward, (Iolo Morganwg), Journey 3 Llandeilo to Cardiganshire and the north, c. 1800, NLW MS 13156A, p. 194, image 200

1802

15.6.1802

Come to Sputty [Ysbyty Cynfin] after a tedious ride over a desert; and found once more a land of hedges Ysbyty village consists of a chapel and one house. A large stone pitched on end in the Eastern fence of the churchyard. ^It is part of a druidical circle. Iolo.^ Enquire the tradition about it. ?Is an Rector of Llangynog be not the vicar here? If so write to him.

Davies, Walter, NLW MS 1755Bii, Notebook 1, Diary and Journal no V continued from no IV, p. 25

Davies was accompanied by Iolo Morganwg on part this tour. Iolo became ill and was forced to stay at the near-by inn at Pentre Brunant (Cwmystwyth) for a couple of weeks to recover.

1803

The visitors of these scenes seldom go beyond the Devil’s Bridge, unless their road lies for Llanidloes; and even then, they are apt to pass a very curious spot, lying a little to the left of Yspytty ‘r Enwyn [Ysbyty Cynfyn], without notice, for want of information. … There is in the churchyard a large, upright stone monument, with the characters entirely defaced. I could not learn that any tradition was attached to it in the neighbour-hood; and there was nothing in its shape or appearance, particularly to distinguish it from similar erections, to be met with in every part of this country.

Malkin, B.H., (1769-1842), The Scenery, Antiquities, and Biography of South Wales from materials collected during two excursions in the year 1803. (1804), pp. 369-370

An abridged version of Malkin’s book was serialised in the ‘Monthly Review’, vol. 47, (1805)

See a revised version of this, published in 1807 (below).

1805

Passed through the village of Yspyttyr Enwyn, in the cemetery of which we noticed some ancient pillars.

Mavor, William Fordyce, (1758-1837) A tour in Wales, and through several counties of England: including both the universities; performed in the summer of 1805, (London: 1806), p. 191

The British Tourist’s or Traveller’s Pocket Companion, through England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland … in 6 volumes, vol. 5. 3rd edition improved and much enlarged, by William Mavor, (London: Sir Richard Phillips, 1809), p. 233

Included in A Collection of Modern and Contemporary Voyages and Travels, Volume 1, (Sir Richard Phillips, 1810), p. 73

1807

In his second edition, Malkin made some additions, marked here in italics.

The visitors of these scenes seldom go beyond the Devil’s Bridge, unless their road lies for Llanidloes; and even then, they are apt to pass a very curious spot, lying a little to the left of Yspytty ‘r Enwyn [Ysbyty Cynfyn], without notice, for want of information. Kenwyn is a name frequently found in history, and in old genealogies. What Kenwyn was the founder of this hospital I have not been able to discover.

There are in the churchyard large, upright stone monuments, with the characters entirely defaced. I could not learn that any tradition was attached to them in the neighbourhood; and there was nothing in their shape or appearance, particularly to distinguish them from similar erections, to be met with in every part of this country. I have from numerous appearances in Wales, as well as from a great many passages furnished to me by my literary friends in old Welsh writers, whether historians or poets, been fully persuaded that the first British Christians used the Druidical places of worship in the open air, within large circles of stones, like those of Stone Henge, and Rollrich, or as some call it Rollright, in Oxfordshire. The church and church-yard of Yspytty Kenwyn may be adduced as an instance of this. The church has been built within a large druidical circle or temple. Many of the large stones forming this circle still remain; and the fence around the church-yard is filled up by stone walling in the intermediate spaces.

Malkin, B.H., (1769-1842), The Scenery, Antiquities, and Biography of South Wales from materials collected during two excursions in the year 1803, (second edition with additions, 1807), Vol. 2, pp. 103-104

The description of the circle is like that for Tregaron (also added to the second edition).

1808

In the churchyard are four stones so placed as to form the quarter of the circumference of a circle. The largest of these is that standing to the east, and measures about 11 feet above ground, five feet six inches in breadth, and about two feet thick. Two of the others form at present the gate posts, and stand to the southward. This was, in all probability, a druidical circle, and occupied the site of the present church. The other stones perhaps were broken to pieces to build the Christian edifice. And perhaps this circumstance may account for the name Cenvaen, i.e. stone-ridge; …

Meyrick, S.R., The History and Antiquities of the County of Cardigan, (1808), Ysbytty C’env’n, p. 373, (1810 edition), p. 269?; (2nd edition, 1907), pp. 298-299

[He said more about druids and stone circles in his introduction on pp. lxxxiv – lxxxvii, in which he listed three stone circles in Cardiganshire: Dyffryn Castell, Ystrad Meurig and Alltgoch, but not Ysbyty Cynfyn.]

1808

[To Llanidloes from the Devil’s Bridge] Pass through the village of Ysbutty’r Enwyn, in the church-yard of which are some ancient pillars.

[Nicholson, George, (1760-1825)], The Cambrian Traveller’s Guide, in every direction containing remarks made during many excursions in the Principality of Wales augmented by extracts from the best writers, (1808), column 516

See below for the 1813 and 1840 editions.

1808

14.7.1808 Thursday

Ysbytty [Ysbyty Cynfyn] which is built within the area of a Druidical circle, three stones of which are still visible.

Colt Hoare, Richard, Tour of North Wales, Cardiff Central Library, ms 4.302.3, f. 65

Richard Fenton, who accompanied Colt Hoare on at least part of this journey, did not mention this site in his surviving journals, but did so in his A Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire, (1811) (below)

1810

Rees’ account is derived from Meyrick (1808).

Ysbyty Ce’n-faen. In the churchyard are four large stones placed upright in the ground and forming the periphery of the quadrant of a circle. The largest is eleven feet in height, and nearly six feet in breadth. They appear to have been a part of a great circle of the kind usually denominated druidical, within which it appears the present church was built. It has been conjectured that the name of the place, Cefn-y-faen, the “stone ridge,” (Literally, the Ridge of the Stone or rock), might have been derived from this ancient erection but its derivation is more probably to be sought in the rocky bank immediately behind the church, composing one of the lofty shores of the Rheidol.

Rees, Thomas, A topographical and historical description of Cardiganshire, (1810), pp. 441-442 part of Rees, Thomas, The Beauties of England and Wales: or, original delineations, topographical, historical and descriptive of each country, South Wales, volume 18, (London, 1815), p. 441

Iolo Morganwg was in correspondence with Thomas Rees but no letters between them on this subject survive before 1813.

1811

It is generally observed, that Cromlechs and other relics of druidical worship are often found in the neighbourhood of Christian churches, which were purposely built there to purge the idolatry; or for the reason that influenced the first missionaries in Ireland, who, in order to prevail in greater points, were forced to comply with some of the druidical superstitions; and instead of abolishing them entirely, thought it best to give them only a Christian term, for not being able to withdraw them from paying adoration to erected stones, they cut crosses on them, and raised temple to the Living God near the scene of their idolatrous worship. There is in Cardiganshire a church built in the centre of a druidical circle [presumably Ysbyty Cynfyn], as Cordiner tells us the church of Berachie, in Scotland likewise is.

Fenton, Richard. A Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire, (1811), p. 19

1813

Davies clearly saw the site in this year and cited Iolo Morganwg as the source of the identification of the stones as a Druidical circle, but it is not clear whether the measurements were his or Iolo’s.

Came to Ysbyty Kenvyn a small chapel, attended only by one house, and that selling ale.

Iolo Morganwg saw here in the churchyard wall, the vestiges of an ancient Druidical circle. There are large upright stones in the wall, two serving for gateposts – a 3rd short and thick a 4th at somewhat regular distance, thick, but not higher than the wall a 5th higher up – larger, and about 7 ft above the ground. They are of the inundated clefty mountain rock, not uncommon in these parts.

Davies, Walter (Gwalter Mechain) NLW MS 1755Bii, notebook 7, Diary 1813 continued from dated Nov 22 1812 including a journal to S Wales 24th May 1813, pp. 15/9v

He mentioned this visit in a letter to a friend, noting that he was there on the 26th May, 1813

Stopt at Ysbyty Kynvyn to view the Druidical pillars in the churchyard wall.

Letter, Walter Davies (Gwalter Mechain) dated Manafon 24.6.1813, to John Jenkins

1813

The measurements of the large stone suggest that Wood derived his information from Meyrick.

Here [near Parson’s Bridge] a small stream from the east pays it tribute [to the Rheidol] running by the church of Spytty C’env’n, a chapel of ease to Llanbadarn Fawr, from which the Rheidol is distant about half a mile. There are four large stones in the churchyard: the largest stands to the east, and measures about eleven feet high, upwards of five feet broad, and two thick; two of the others are used a gate-posts, and the forth stands between those and the first mentioned. These stones are supposed to have been part of a Druidical circle, within which the church has been built. The rest may have been destroyed, and converted to other purposes; the common fate of such remains.

Wood, J.G., The Principal Rivers of Wales Illustrated, Consisting of a Series of Views from the Source of each River to its Mouth, Accompanied by Descriptions, Historical, Topographical, and Picturesque, (1813), part 1, p. 173

1813

The 2nd edition of Nicholson’s Cambrian Traveller’s Guide includes two differing descriptions of the site:

Passed Spythy C’enfaen, where the church seemed to be without bells, a large unhewn stone, about 7 feet high, stood on the N. side of the yard. [Derived from Lipscomb, (1799) above]

[To Llanidloes from the Devil’s Bridge] Pass through the village of Ysbyty C’en fyn, a chapel of ease to Llanbadarn y Creuddyn ucuaf. The church consists simply of a nave. {Monument to Thomas Hughes.} In the yard are four large stones, forming the segment of a circle. The largest measures 11 feet above ground, 5 feet 6 inches broad, and about 2 feet thick. Two of the others form gateposts. These are probably part of a druidic circle, the rest of which were broken up to form this Christian edifice. [Derived from Meyrick (1808)]

[Nicholson, George,] The Cambrian Traveller’s Guide, in every direction containing remarks made during many excursions in the Principality of Wales augmented by extracts from the best writers, (1813), cols 1092, 1096

See above for the 1808 edition and below for the 1840 edition.

1823

11 July 1823 (Friday)

Yspytty Kenwyn, … There are in the church-yard many upright monumental stones, and these, as well as the circular form of the consecrated ground, have induced Mr. Malkin to believe that this was formerly a large Druidical circle or temple. We went through the church-yard, {to Parson’s Bridge}

Freeman, George John, Sketches in Wales; or, A diary of three walking excursions in that principality, in the years 1823, 1824, 1825. (London, 1826), pp. 36-37

Print of ‘Pont Bren’ [Parson’s Bridge], on stone by T.M. Baynes, printed by C. Hullmandel.

1823

Q. Is there any thing else deserving notice in this vicinity?

A. In the church-yard of Yspytty Ce’n Faen, a little to the north of Hafod, are four stones, part of a druidical circle. The footpath through the churchyard conducts to one of the most romantic parts of the valley of the Rheidol, where is a curious foot bridge, called the Parson’s Bridge.

Pinnock, W., The History and Topography of South Wales with Biographical Sketches, (London, 1823), p. 25

1831

Yspytty Kenwyn was formerly connected with Strata Florida Abbey. In the churchyard are several upright monumental stones, from which, and the circular form of the enclosure, it has been inferred that this was once a Druidical temple.

Leigh’s Guide to Wales and Monmouthshire … (1st edition, 1831), 129-130; (2nd edition, 1833), pp. 133-134; (4th Edition, 1839), pp. 139-140

1833

Antiquities – In the churchyard of Ysbytty Cynfyn are four large stones standing upright in the ground and forming part of a Druidical circle.

Lewis, Samuel, Topographical Dictionary of Wales, (1833), (and 1845) ‘Cardiganshire’

1838

Leaving the Devil’s Bridge for Llanidloes, at the distance of 1 mile, is Yspyty Cynfyn, … There are in the church-yard many upright monumental stones, and these, as well as the circular form of the consecrated ground, have induced Mr Malkin to believe that this was formerly a large Druidical circle or temple.

Bingley, W., Rev, (1774-1823), Excursions in North Wales, including Aberystwith and the Devil’s Bridge intended as a guide to Tourists by the late Rev W Bingley. Third edition, with corrections and additions made during excursions in the year 1838, by his son, W. R. Bingley, (London, 1839), p. 184

Some of this is from Freeman, (1826), above.

1840

The wording of this is slightly different to that of the 1813 edition (above).

[To Llanidloes from Devil’s Bridge] Pass through the village of Ysbytty Cenfaen, a chapel of ease to Llanbadarn-fawr, … In the yard are four large stones, forming the segment of a circle. The largest measures 11 feet above ground, 5 feet 6 inches broad, and about 2 feet thick. Two of the others form gateposts. These are probably part of a druidic circle, the rest of which were broken up to form the chapel.

Nicholson, Emilius, Nicholson’s Cambrian Traveller’s Guide, in every direction containing remarks made during many excursions in the Principality of Wales augmented by extracts from the best writers, Third edition, revised and corrected by his son, The Rev. Emilius Nicholson, (1840), p. 508 (from Lipscomb, 1799, above) and p. 509

Partly derived from Meyrick (1808).

1845

Plot 814 is ‘Yspytty Cynfyn’ shows the churchyard as the shape of a quadrant of a circle. The long rectangular building on one side is presumably St John’s church, but if so, it is incorrectly aligned – it should be almost parallel to the road

Tithe map, 1845

1848

The church of Yspytty Cynfaen … In the churchyard are four large stones, so placed as to form the quarter of the circumference of a circle. The largest of these is that standing to the east, which measures about 11 feet above the ground; two of the others form at present the gate posts, and stand to the southward. This was, in all probability, a Druidical circle, and occupied the site of the present church; the other stones were probably broken to pieces to build the Christian edifice.

Morgan, T.O., New Guide to Aberystwith and its Environs, (1848), p. 107

Morgan, T.O., New Guide to Aberystwith and its Environs, (2nd edition, 1851), p. 112

Morgan, T.O., New Guide to Aberystwith and its Environs, (3rd edition, 1858), pp. 112-113

4th Edition, 1864

5th Edition, 1869

Another edition, 1874, (not by T.O. Morgan)

Another edition, 1884, (Town Library collection)

Derived from Meyrick (1808), or Nicholson’s guide.

1852

In the neighbouring churchyard [of Yspytty Church] are several erect stones, believed to have formed a portion of a Druidical circle.

Black’s Picturesque Guide through north and south Wales and Monmouthshire, (Edinburgh, 1852), p. 212 and many subsequent editions up to early 20th century, some split into north and south editions.

1852

Mae gweddillion henafiaethol Sir Aberteifi yn dra lliosog. Ym mynwent Yspytty Cynfyn, y mae pedair o gerrig mawrion yn eu sefyll, yn ffurfio rhan o gylch Derwyddol. …

(The antiquarian remains of Cardiganshire are very numerous. In Yspytty Cynfyn cemetery, there are four large stones standing, forming part of a Druidical circle. [Lists other stone ‘circles’ in Ceredigion – a pair of stones at Llanlwchaearn; Alltgoch near Lampeter; Gwely Taliesin [Bedd Taliesin]]

Anon, ‘Hanes Sir Aberteifi’, Yr Haul, Cyf. 3, rhif. 36, (Rhagfyr 1852), pp. 384-385

1854

There are Druidical remains in Ysbytty [Cynfyn] churchyard.

Cliffe, Charles Frederick, The Book of South Wales … (3rd edition, 1854), pp. 288-290

1858