In the language acquisition process, children learn to imitate their parents’ use of language. They start out by babbling, trying to utter simple sounds of consonants and vowels. As they grow up they start to mix and match those sounds to make a word. But before they can achieve an adult grammar (a fully developed mental grammar), there’s a critical stage, which all children have to encounter—the telegraphic stage, in which they attempt to put simple words into a sentence, like “Mom give cookie” (‘Mom, give me a cookie.’) and “Doggie not bite” (‘The dog doesn’t bite.’). The words they use in this stage are called content words.

Content words are lexical morphemes that have a semantic content; i.e. they have a particular meaning on its own. They are usually open class words because new content words can be easily included to the language. For example, nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are content words, because they all refer to semantic concepts. However, we also consider derivational affixes and negation as content words because they change the meaning of a base form.

On the other hand, function words or grammar words are lexical morphemes that have a grammatical relation rather than refer to a semantic concept. They just have to be there to make a grammatical sentence. For instance, articles, conjunctions, prepositions, auxiliaries, interjections, particles, and inflectional affixes are function words.

Most of the time, it’s quite easy to distinguish the content words from the function words. Words that refer to an object, an abstract idea, an action, an attribute, and a manner are said to be content words. Words that don’t refer to any meaning but must be there to make a grammatical sentence are function words. But some words appear to be both! For example, ‘will’ as a noun (content) means a motivation to do something, while as an auxiliary (function) conveys the futurity of an action. In this case, we say that the word ‘will’ is in the process of grammaticalization.

Grammaticalization is a process of language change whereby a content word (or a cluster of content words) becomes a function word. This process takes place when a content word is used so frequently that it starts losing its core meaning over time.

Grammaticalization is characterized by the following processes.

- Semantic bleaching (desemanticization): a word loses its semantic content. As a content word is frequently used, it establishes a structure with surrounding words and becomes a partial function word. As its functionality strengthens, the semantic content gradually disappears.

- Morphological reduction (decategorization): a word changes its content-bearing category to a grammatical structure. This process is a result of semantic bleaching.

- Phonetic erosion: a word loses its phonological properties as a free morpheme to become a bound morpheme, such as I’m going to > I’m gonna > I’mma. Bernd and Kuteva (2002, 2007) propose four kinds of phonetic erosion: the loss of phonetic segments (being full syllable), the loss of suprasegmentals (stress, tones, or intonation), the loss of phonetic autonomy (being an independent syllable), and phonetic simplification.

- Obligatorification: when a content word is used in a specific context in a specific way, it may become more grammatical over time. [obligatory means necessary.]

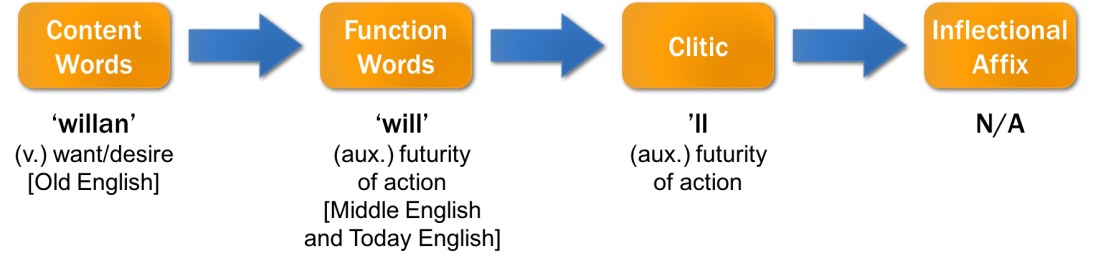

In the process of grammaticalization, a content word transforms itself into a function words over time. Hopper and Traugott (2003) propose the cline of grammaticalization as follows.

content word ⇒ function word ⇒ clitic (contraction of full word) ⇒ inflectional affix

The above process is also known as the cycle of categorial degrading (Givon, 1971; Reighard, 1978; Wittmann, 1983). For example, the auxiliary ‘will’ follows through the cline of grammaticalization shown below.

In Old English, the verb willan means to want or to desire. The verb was then grammaticalized to become the auxiliary will in Middle English and Present Day English. Later due to its frequent use, it becomes contracted into clitic ’ll. It’s assumed that it may become an inflectional affix indicating the future tense some time in the future.

Unidirectional Hypothesis. Most linguists assume that process follows Hopper and Traugott’s (2003) cline of grammaticalization. However, this assumption is challenged by very rare counterexamples of degrammaticalization, where several function words become content words under specific circumstances. For example, preposition ‘up’ is degrammaticalized to become a verb, as in “The company upped our salaries by 10%”.

References

- Heine, Bernd and Tania Kuteva. The Genesis of Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Heine, Bernd and Tania Kuteva. World lexicon of grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Givon, Talmy. “Historical syntax and synchronic morphology: an archaeologist’s field trip”, Papers from the Regional Meetings of the Chicago Linguistic Societv, 1971, 7, 394- 415.

- Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Traugott. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Reighard, John. “Contraintes sur le changement syntaxique”, Cahiers de linguistique de l’Université du Québec, 1978, 8, 407-36.

- Wittmann, Henri. “Les réactions en chaîne en morphologie diachronique.” Actes du Colloque de la Société internationale de linguistique fonctionnelle 10.285-92. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 1983.

- Aitchison, Jean. Language Change, Progress or Decay? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Copyright (C) 2018 by Prachya Boonkwan. All rights reserved.

The contents of this blog is protected by U.S., Thai, and International copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution of the contents of this blog without written permission of the author is prohibited.