Late last year as I languished in my feels after bingeing The Heike Story, I joined a centuries old tradition. Across many years, media, and languages Heike Monogatari has drawn audiences into its intricate tragedy, weaving the tale of one noble family’s arrogance and inevitable downfall against the lush and philosophical backdrop of medieval Japan. It’s an epic in the truest sense of the word: sprawling in scope, deeply poetic, and intwined in a glorious tradition of oral storytelling. It may seem like all this should make it nigh-impossible to adapt effectively, but somehow Science SARU pulled it off—not only successfully playing out the tale in eleven episodes, but successfully getting me, and many other very modern viewers, hooked emotionally.

Part of this, of course, is the enduring power of the story itself, but part of it is how the story is told. The Heike Story employs a clever narrative trick to play out the epic while also playing with the epic, adding new and very metatextual dimensions. And that narrative trick’s name is Biwa.

Biwa is the central character in The Heike Story, the first we’re introduced to and the one we follow throughout the whole narrative arc. Biwa is a psychic child who foresees the downfall of the Taira clan after some of their lackeys kill Biwa’s father. Biwa travels to the Taira estate to pass on this accursed knowledge, only to be taken in by the family’s eldest (and most compassionate and sensible) son. Biwa reluctantly integrates into the household, and quickly finds themself at the centre of an unfolding war story for which there can be no happy ending.

Biwa, though, was not a character in the original. Biwa is a modern addition, and a creative decision that’s massively interesting—to me, at least, with my love of playful takes on mythos and retellings about retellings. Biwa is one fascinating answer to the question of “how do you (re)tell an epic?” It might seem an odd choice at first. Inserting a new character does seem like it could get silly pretty quickly: after all, how do you justify sticking this new figure into an established narrative without changing the story everyone is expecting?

Well, that’s just it: Biwa doesn’t change the story, though they’re swept up in its tide. Biwa is here to bear witness to, and record, what will become Heike Monogatari, less of a modern audience insert and more like the abstract ideal of the story(teller) itself.

Biwa is an in-between figure: a commoner’s child living among nobility, simultaneously a beloved foster family member and a permanent outsider. A “girl dressed as a boy”, able to roughhouse with Shigemori’s sons as well as be a sisterly confidante to Lady Tokuko. Biwa’s involvement in the Taira clan’s tale begins when they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, yet they end up always exactly where they’re supposed to be in order to tell that very tale. So, who is Biwa? No one at all, yet the most important person in the story-world.

What is Biwa? There is a surreal moment a few episodes in where it dawns on you that time has passed, but Biwa looks the same. Their child-shaped character design has stayed static while Shigemori’s sons have grown up into lanky young adults. No one really comments on this, and I’m left to assume it’s something like Biwa’s all-seeing blue eye: recognised as unusual and a bit freaky by the laws of the story’s realism, but it would be impolite to point it out.

Is Biwa… human? Well, Biwa’s A Narrator. This lets them transcend the normal rules of space, time, and human mortality. Biwa is not so much a character, but a part of the story.

Biwa can see the future with that blue eye, but can’t affect the future they see. They are trapped in the role of observer, never changing as the events unfold around them and never able to change the events either. But Biwa isn’t a neutral observer—they come to know the “characters” in their epic intimately, considering many of them family. Grief rips through Biwa with each death, enhanced by that knowledge that there was nothing they could have done.

Inevitability is a big part of tragedy (as a genre) and this storytelling feature hammers it home. Biwa can act as a stand-in for viewers familiar with the story, who already know what terrible fates are going to befall the characters and have to just, well, sit and watch it happen. Knowing the future doesn’t necessarily “spoil” a well-told story, and they can still sting like hell hundreds of years later. If you’re not familiar with the ins and outs of Heike Monogatari, Biwa’s visions help you get up to speed, and draw you into the sense of impending doom hanging over the story. You care, because Biwa cares.

This added personal perspective helps Heike hook into your emotions. While it would be inaccurate to call these old tales “impersonal” or “detached”, the sense of scale in these bardic epics—stories covering many years and huge casts of characters—can understandably throw modern audiences off. Omniscient, all-seeing, and objective (if poetic) language isn’t typically how we tell stories these days, but it’s what we often associate these older tales with. You’re not “in the head” of any given character, usually, but are seeing the events unfold from afar, described in sweeping atmospheric tones by a poetic narrator or chorus. It’s a fine way to tell a saga, of course, though it can render these stories a little inaccessible to new readers.

Focalisation through character is a way that many retellings and adaptations play with convention, telling the same story but drawing the focus down to the micro rather than the macro—see, for example, Madeline Miller’s novels, which retell events from The Iliad and The Odyssey through a deeply personal lens. These new takes on familiar stories are fresh and entertaining (and heartbreaking) but they also play a fun metatextual game that shows us how important storytelling is to getting these ancient themes and plot beats across. It’s the human element, after all, that makes these tales tick, and building that question of why we tell them into the narration itself lets that shine.

The Heike Story making Biwa the narrator makes for an effective emotional hook, but it also throws around all these intriguing questions about the nature of narration itself. Biwa is a one-kid homage to the tradition of oral, bardic storytelling, the method through which many of these epics from across the world survived and evolved until they were written down.

A blind monk told the tale to a disciple who transcribed it in 1317, which became the original written form that all other versions and translations followed. Biwa goes blind at the end of the final episode, as a tribute to tradition and to indicate they’ve seen everything they need to see. The story is over, and all that’s left to do is tell it. Biwa’s once-family is dead, but they live on in Biwa’s words and in the strumming of the strings. In that respect, they’ll live forever.

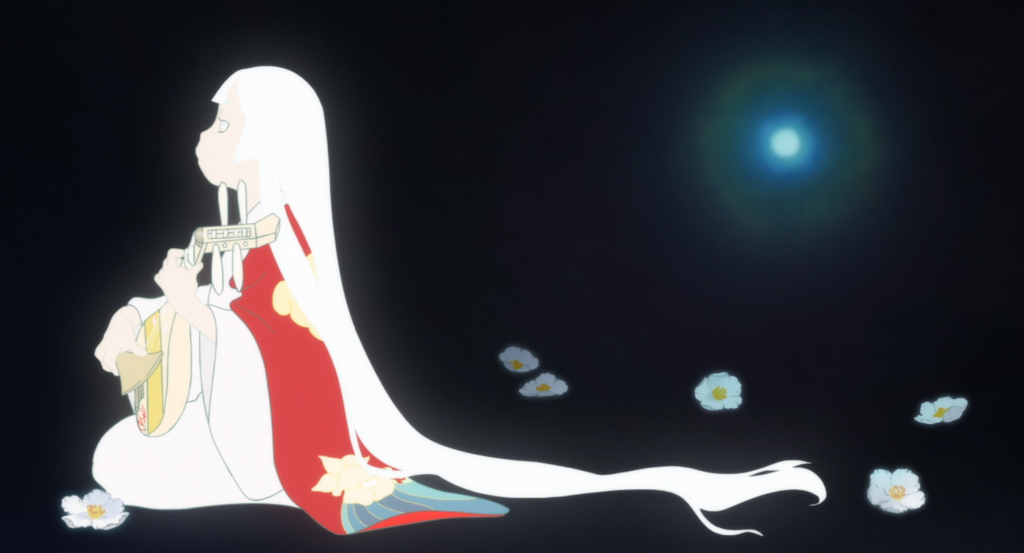

In a very meta sense, the anime itself is a testament to the Taira clan’s immortality: these people all perished centuries ago, but here they are, a new translation of their deeds and deaths ringing out in TVs and streaming apps around the world. Nothing is permanent, that’s what Biwa tells us, and that’s what it says in the very first line of the Monogatari itself. But with stories, we can steal a little permanence. Biwa’s sort of timeless. Where, and when, do those scenes of the white-haired Biwa chanting the prose poetry take place? It doesn’t matter exactly. White-haired Biwa, in that black space, is everywhere at once: in the liminal space where Story takes form.

Biwa’s words ensure the Taira clan lives forever, singing out in a voice that ultimately gets subsumed as The Narrator. The implication here is that Biwa may well have been a part of the original events of the epic, but they simply never mentioned their own actions and words, thus vanishing into the narration while still remaining alive and well in the tale. It’s a clever device that reminds us, as viewers, that stories come from someone. Reconceptualising The Tale of the Heike as not just a war story, but a story of one heartbroken bystander’s grief, puts a new spin on it and forges a new emotional connection with the material.

Biwa is the platonic ideal of The Narrator, an intangible collector and archivist of stories. The name they give themself is the same as the instrument they play. Biwa is the biwa, the literal instrument through which the tale is told. Biwa could be a very impersonal, abstract, conceptual character—which would have been extremely cool—but instead, they’ve been written as deeply emotional and human. They have ascended to Narratorhood out of love, breaking all the rules of realism and human experience to embody storytelling itself. Why do we tell tragedies? Why do we return to these old tales? Biwa is the answer.

Maybe Biwa didn’t exist, but somebody like them did: somebody was moved by this tale of arrogance and politics and death enough to make sure it survived hundreds of years. And each person who offers a new translation, a new retelling, a new adaptation, is part of that work, too. Everyone who has ever been part of this evolving story is a little bit Biwa. Everyone who worked on The Heike Story no doubt brought their own perspective to it, their own losses and loves. Biwa is the character who focalises all of that: that noble and melancholy need to tell stories, even tragedies, to make sure that it’s all worth it.

Like this blog? Consider buying me a coffee or supporting me on Patreon!

Pingback: Piece of Cake: February ’22 Roundup | The Afictionado

Pingback: National Novel Fighting Month: November ’22 Roundup | The Afictionado