All About That Fat, ’bout That Fat (yes, blubber!)

…Ok, bad pun reference to Meghan Trainor’s song, but I need ways to amuse myself here on the Ice, right? We had a seemingly neverending series of storms from late December through January that made it hard for me to connect to the internet, but now that things have calmed down a bit I can get back to writing about life in the field. And today I’m talking about weddell seal pups, how amazingly fast they grow, and the purpose of blubber in polar animals.

In the end of November I hiked out onto the sea ice towards the pressure ridges that I explored last year, and on my way I passed a baby weddell seal pup with its mother on the ice. I’ll admit I’m a total sucker for baby animals, particularly chance sightings of wildlife in their natural habitat, but I still stayed a fair distance away from the seals so that I wouldn’t disturb the pair or make the mother feel too defensive for her pup. Luckily I had a zoom lens on my camera that let me take a few decent photos from farther away on the ice, and I’m pretty pleased with a few of the shots I was able to take.

The weddell pup was very cute but I was surprised by how *large* it was- at only two weeks old, this seal was already around 80 pounds. I spoke to a few of the seal biologists at McMurdo station after my sea ice hike and learned that this pup was 4ft long and weighed ~58 pounds when it was born, and continued to gain 4 pounds per DAY for the first six weeks of its life. In order to help the seals grow quickly, the milk produced by weddell mothers is so extremely fatty (60% pure fat) that it has the consistency of melted wax. This helps the pups gain enough blubber to keep warm in the Antarctic cold, and after six or so weeks, when the pups have quadrupled in weight (now approximately 240 pounds), they begin hunting and eating small fish and krill.

They continue to grow until they reach an average of 1200 pounds and are 11ft long, and as active adults they eat an average of 110 pounds of food per DAY. It’s hard for me to imagine that massive amount of food; a seal eating a pile of krill approximately the weight of my entire body on a daily basis. Even when compared to their total body mass, that appetite would be proportional to if I ate 11.4 pounds of food per day (compared to the 3-4 pounds of food eaten/day by the average healthy American adult). Needless to say, these seals are enormous. Even when I’ve been closer to them when adult weddells have approached near me in the past, I wouldn’t have imagined they were 1200 pounds just because they don’t stand up or tower over us in any way, so somehow I think it’s harder to envision their true size when they’re laying down. They remind me a bit of water balloons, sort of ‘spreading out’ their body mass when they lie on the ice, but that blubber is actually very dense and contributes 40% (nearly 500 pounds) of their weight.

Alex Eilers, a PolarTrec researcher, comparing her size to a weddell seal during a veterinary study. It’s hard to imagine that the seal is 10x her body weight. (photo courtesy of Alex Eilers/ PolarTrec)

In order to find out all of those facts I did a bit of research online, and while reading I learned a bit more about the purpose of having blubber- sure, it’s to keep warm, and it provides a source of energy when food is more scarce, but what’s the advantage of having more fat instead of having fur to keep warm? The answer, I learned, has to do with pressure. Sea otters have the thickest fur of any animal (one million strands of hair per square inch of skin!) which traps air in the fur layer and helps insulate the otters from cold water. Otters sometimes ‘roll’ in the water to introduce more air into their fur and help keep them warm.

Sea otters, which live in the Northern Pacific Ocean, have the densest fur in the animal kingdom. (Photo courtesy of Mike Baird and wikimedia commons)

Weddell seals, on the other hand, do not have a lot of fur. When weddells hunt, they can dive up to 2000ft below the surface in order to find food, but the deeper they dive, the greater the pressure of seawater pushing against their bodies. Thick fur wouldn’t help seals in that situation because fur is compressible– the large water pressure in deeper water would squeeze all ‘warming’ air out of fur. Blubber, on the other hand, is not very compressible, so it can provide a layer of insulation for seals even deep below the ocean surface.

Weddell seal beneath the ice, insulated by its thick layer of blubber (Photo courtesy of Steve Rupp and PolarTrec)

Early explorers to Antarctica like Robert Scott and Ernest Shackleton used the high fat content of seal blubber for fuel and food, and during a visit to Cape Evans this season I actually saw (and unfortunately, smelled!) the enormous 104-year old blubber pile stored by Captain Scott’s team in 1911, but that’s a blog article for another day.

Cryolakes and Snoutburn

Well, I said I’d be busy for the next few weeks and that has definitely been the case. I wanted to show you what it looks like to collect water from cryoconite holes, but my camera only works for ~10-15 minutes on each glacier before the battery needs to be recharged. (I can recharge the batteries slowly using power from our solar panels as long as the sky isn’t cloudy.) Batteries don’t work very well in extremely cold environments. I’ve tried my best to burrow the camera inside my jacket to keep it warm, but I need to take it out in order to film anything and it quickly loses power when exposed to the windy air. A few of my youtube clips have little “shiver” moments where the video shakes more than normal, which is another sign of the battery struggling in the cold.

In warmer conditions high volumes of meltwater can carve narrow channels into a glacier’s surface and expose denser layers of blue ice underneath. Usually water can only carve shallow channels 2-5 inches deep, but if new melt gets funneled through the same pathways each summer the channels will deepen. Multi-year channels are particularly common next to “cryolakes”; large indents on a glacier surface that are roughly the size of a smaller backyard swimming pool. Cryolakes usually start out as cryoconite holes (the small pockets of water and sediment that I use to collect meltwater), but as the holes get larger each year, they can trap more sediment blown by the wind and help melt more of the ice around it.

The sun never sets during Antarctica’s summer (see an explanation here) and for the majority of the summer it remains lower in the sky close to the horizon. Instead of shining directly above you, the low angle of sunlight in Antarctica will hit vertical surfaces (the ice walls around cryoconite holes) more directly than the horizontal glacier surface. Eventually the holes become so large that one of the side walls will melt away and the water will spill out from the shallow side. From that point onward, cryolakes essentially become big empty pools with a large bottom layer of dirt. Meltwater from uphill channels can spill into the pool, flow out through the ’empty’ wall, and connect to more cryolakes downhill. This causes deeper surface channels like the one in this video because all of the water that falls into the lake will try to drain through the downhill side of the pool, and a larger volume of water is all funneled through one spot.

I shot this video quickly because it was a rare moment when my camera actually had enough power to function (for a short while). It shows a series of cryolakes that serve as little steps for water flowing into and out of the pools. I’m out of breath in the video because I’d just hiked up the glacier, and you can see the deep sunburn on my face in the shape of a beard/ mustache.

This is a lovely condition many of us refer to as ‘snoutburn’. It’s unpleasant but not extremely painful. As I said earlier, the sun never sets during Antarctic summer and the light is very powerful even though it’s cold. If you’ve ever gone skiing you may know that light bounces off of snow/ ice and can burn your face in the winter, and this effect is very strong on the glaciers I study. I try to be cautious and I use a TON of sunscreen every day, but sometimes it’s a bit hard to avoid snoutburn. The reason for it? People tend to get runny noses in extremely cold weather. It’s not a cold/ flu, just a constantly runny nose. (Not glamorous, but true.) This means you end up wiping all of the sunscreen off your lips/ chin below your nose so much more often than you can reapply more sunscreen, and you’ll get a very localized sunburn on your lower face. It gets dark, it peels, and it can make you look like you have a weird mustache.

A lot of men in Antarctica grow beards to help protect their skin from burning, but this can lead to the even less-glamorous situation where their runny nose freezes ONTO the beard. No thanks. I don’t have the option to grow a beard anyway, but you can tell I’ve been working on glaciers quite a lot in the past two weeks by the look of the burn, and it explains why the bottom of my face is weirdly tanned in today’s video.

The Mountains Are Alive… With the Sound of Glaciers

[Written January 15, 2015]

Living in a small Antarctic fieldcamp can be a very quiet experience. Without the sounds of traffic, dogs barking, doors slamming, strangers talking, and cell phones ringing, for the most part all you hear is the wind. It doesn’t take long to fall into a routine with your campmates where you know what they want without speaking, and as chatty as I am there’s less to talk about halfway into a four month season with the same two people. Every morning we use a safety radio to call the main base at McMurdo Station and confirm that we’re alive and safe, but the radio operators at McMurdo need to keep the frequencies open to other calls so it’s usually a 20-second conversation. Our solar panels screech when we rotate them towards the new angle of the sun a few times each day. The rest of our time is spent in an oddly and somewhat hypnotizingly silent landscape.

One of the things I love about the field is how much you become attuned to your environment, and it makes me feel so much more connected to this place. “Genius loci” is a somewhat obscure latin phrase used in anthropology and architecture that I’ve always found beautiful. It means “the spirit of place” and in modern language it refers to how people may find particular locations so meaningful that it influences their personal identity. Don’t worry, I haven’t been in Antarctica long enough to get “toasty” (a little bit nutty from the isolation) and I don’t think “I AM Antarctica”. But without much contact with the outside world, my brain becomes entirely focused on being here and I’ve picked up on some of the tiniest details that keep me aware of my surroundings. It’s so quiet that I know the specific sound my footsteps make when I walk across particular lakes (the sound is different on each lake), and I can tell when I’m walking towards a weaker section of ice by VERY subtle changes in the tone of my steps. My research involves collecting liquid from little pockets of meltwater (called cryoconite holes) on glaciers. The pockets are sealed underneath a layer of ice, and my ice screw can’t crack through more than 4 inches of ice without contaminating the water inside. Ice lids can be as thin as tin foil, or more than 1ft thick. The thicker an ice lid is, the less water there will be underneath it, and I need to be able to collect at least 2 liters of water for each of my samples. So I use a sharpie marker to gently tap on the ice lids, and it gives me an idea of how thick the lid is and how much water there may be beneath it. Everything in Antarctica is subtle… until now.

The melt season has finally started. If you’ve been reading this blog you know that this is what I’ve been waiting for; this is the time of year my research is particularly important. I could hear the water for a few days before I could see it because it began with meltwater flowing *inside* the glacier. A few days later the combination of higher temperatures and the ionic pulse caused meltwater to gush down glacial waterfalls and feed the Dry Valley’s ephemeral streams. I can hear the sound of waterfalls from my tent, and now that the ‘hydrologic tap’ has turned on I’ll have a lot more fieldwork to do in order to collect enough data on meltwater characteristics. The melt season occurs in austral summer, but it’s a short 6-week season before temperatures dip well below freezing in austral fall and nothing melts until the next year. So for now, it’s time for me to get my game face on and hike my heart out to all of my field sites. Water makes the Dry Valleys a more dynamic place; it changes the biology, chemistry, and physics of this area. But it also throws off my familiarity with each glacier because I can’t hear the tap-tap sound of my sharpie marker to know where the best cryoconite holes are, and the density of the ice I walk on is different. It sounds like I live next to a river. My glaciers are suddenly strangers again and I need to retrain my senses to “know” this place.

Wondering what it looks like when meltwater is flowing off of a glacier surface? Here’s a quick peak-

.

“Ce est l’Antarctique”

[This post was weather-delayed and was written in the field in January; my experience is below.]

January 14, 2015

Recently I returned to McMurdo Station for what was supposed to be a three-day visit to ship some of my water samples home and stock up on supplies, but bad weather (extremely heavy cloud cover and low visibility) left me stuck there for an additional week before the helicopters were able to return to my fieldcamp. It can be nervewracking when you’re away from the field and have so much work to do there, particularly since glacial melt only occurs during a narrow 2-month summer season each year and spending one or two of your “really important weeks” away from camp can make it feel like your limited time is audibly ticking away. What I have to remember, though, is that the weather is out of everyone’s control- there’s nothing I can do about it, so other than catching up on miscellaneous tasks, worrying about a week of ‘missed’ data won’t actually solve anything. I had to just sit tight at McMurdo base, enjoying the luxury of sleeping in a bed for the first time in months but anxiously waiting to return to the field.

This “flat weather” occurs when clouds descend too low into the mountains. Helicopters can’t fly safely into our mountain range when the cloud cover is low, so my quick resupply at McMurdo station turned into a longer visit as I waited for the weather back at my camp to improve.

There are a variety of ways people address difficulties on the icy continent– at Concordia Station, where I worked in 2012-13, when tough or unexpected situations arose my French colleagues would shrug and say “ce est l’Antarctique”. The translation, “this is Antarctica” is fairly literal, but the meaning behind it tacks on the additional suggestion “…and it was never meant to be easy”.

When I’m asked what the most difficult part about preparing for Antarctica is, I think most people assume I’ll refer to the physical conditioning (hiking, preparing your lungs for high altitudes, adjusting to the cold or sleeping in 24hr-daylight, etc.) but the real answer focuses far more on ‘logistical’ preparation; imagining any and every way that something could go wrong in the field and taking the steps to minimize those complications. If there’s a certain tool you need you’d better bring a spare or two, because there isn’t exactly a Wal-mart nearby to stock up on extra supplies. Need duct tape? Bring a few extra rolls. Use glass bottles like I do to collect samples? Expect a third of them to break. That may not necessarily happen, but I’d rather have a few extra bottles at the end of the year than run out of containers too early.

Helicopters shake things around. Katabatic winds soar down the Antarctic Plateau and tear our tents to shreds. Something that becomes damaged or ineffective when frozen, like lithium batteries or sunscreen, will freeze in your tent when you forget to take it out of your hiking pack and store it in the 2°C equipment shed. Last season my laptop met its demise when an unscheduled helicopter landed at our fieldsite due to weather delays- the helicopter didn’t actually land anywhere near my laptop, which was sitting roughly 150ft away in my zipped-up tent, but we work in a mountain valley filled with magnetic dust, and enough microscopic dust was blown through my tent zipper by the helicopter that it was sucked up by my laptop’s air vents and slowly magnetized and destroyed my old hard drive. Things happen. All we can do is try to adapt to the change.

When it comes to the unexpected, my boss prefers Dwight Eisenhower’s quote; ““In preparing for battle, [or in our case, fieldwork,] I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” What she (and dear ol’ Dwight) mean is that it’s useful to get an idea of what it is you’d like to do, but to keep in mind that there will always be things you couldn’t have anticipated and you’ll need to quickly adapt to new situations. In my case, getting stuck away from my camp for the second time this season means that I won’t have as many weeks of data as I’d hoped for this year. It’s certainly not the worst thing that can happen on a dangerous, icy continent. Keeping an optimistic attitude can be very important in an isolated part of the world like this. So, while I was waking up early every morning in McMurdo to see if the weather had changed and I could get back to my camp yet, I ended up being in town on January 11, 2015, which just so happens to be the day of the Antarctic Marathon.

I wasn’t supposed to be in town that day, but I was. And I had nothing else I could do. I hadn’t trained for the race at all, but I figured, well, when else will I get the opportunity? So I ran the joint McMurdo/Scott Base Marathon across the sea ice near McMurdo Sound along with 63 other people from the American and New Zealand research stations.

————-

I run in the US in order to keep up a strong lung capacity to work in the field, but I never tried to run a 10k or marathon because I couldn’t justify paying the registration fees (often $80-200 per race) required when I can run anywhere else for free. I just didn’t understand the point of paying to run. The day before the Antarctic marathon, though, I was talking to a Canadian pilot I’d met earlier in the season who was describing how excited he was to run. All he wanted was to get his hands on one of the race numbers you pin to your shirt during the race, to try and finish the race, and be able to frame that race number back at home and know that he had accomplished something so great. He seemed SO driven for that goal that he sold me on the race with his passion. I decided I wanted a race number and that sense of achievement too, and since the Antarctic marathon is hosted by a research station and planned by volunteers, it was free. So with less than 24hrs notice, I added my name to the list. I had to search around and borrow an appropriate hat, I didn’t have proper gloves, and I didn’t have a running pack or water bottle (I was only at McMurdo because of weather delays; I hadn’t packed anything for the race) but, well, I didn’t have any long-distance running training either so it was going to be an interesting day.

The day of the race, the 64 of us were shuttled out to the sea ice of McMurdo Sound by large tundra vehicles. I’d guess that at least half of the runners had two or more marathons under their belt already, and I got the sense that I was the only one that hadn’t trained for this race at all. (To be fair, I hike on a daily basis for my job and I wouldn’t consider myself out of shape. I just hadn’t trained for long-distance running, which exhausts a few different muscles than hiking.)

And we’re off! The start of the Antarctic Marathon. Photos during the race itself courtesy of Sage Asher and Kelly Swanson

A few weeks earlier, the IT/communications department at McMurdo decided to restrict the bandwidth on social media websites in order to make sure there was enough internet for science research, and after that change many of McMurdo’s residents commented on how slow the “recreational internet” had become. I knew that I would probably be running more slowly than many of the experienced marathoners, so as a joke I made a sign on my back that said “Still Faster Than Facebook!” to make fun of my slower pace. Sure enough, I was one of the slower runners out of the group crazy enough to run a marathon across the Antarctic sea ice on a whipping cold day, but I was determined to see it through. Running across soft snow is much slower than the mountain trails or streets I’m used to at home, and that ‘sink with each step’ feeling can be brutal on your knees. I also had to remember that since I was on day nine of my weather-delayed-standby to go back to the field, there was a small chance that if the weather cleared up at my fieldcamp I would actually be able to leave McMurdo the next day. That would would mean getting dropped off on top of a glacier and having to hike back to my camp with gear, so I couldn’t push myself to an exhausted limit like some of the other runners because I had to make sure I wasn’t too tired to hike the next day, just in case the weather cleared.

What amazed me about the race itself was how friendly and supportive everyone was during the run. Since I spend most of my season at a three-person fieldcamp in the mountains, I don’t know many of the people at McMurdo Station. During the race, though, the entire group of people I’d either never or ‘barely ever’ met were encouraging me, high fiving me as we passed each other during the route, and cheering on “Yeahh! Faster than Facebook!!” while laughing at the self-deprecating sign on my back. That enthusiasm and strong feeling of ‘energized community’ during the race is what taught me why people pay to do it back in the US. Sure, you can run 26.2 miles anytime, but registering for a race is the chance to be part of the collective spirit in a group and I think I understand that feeling much better now. Even when my knees were killing me to run through the snow, and I walked through part of it to make sure I didn’t strain anything I might need to use in the field later. It hurt. It was cold. The UV radiation was devastatingly strong as it bounced off the snowy sea ice and burned my face, because my sunscreen had been wiped off by sweat and wind and I didn’t know how to carry any more with me as I ran. And that whole time I had a smile on my face, as did everyone who passed me along the way.

Yours truly, staying excited at the halfway point of the race. (Without gloves. Not recommended. 😉 )

Our mobile ambulance / ‘skibulance’ patrolled the route to make sure nobody needed help. While a few of the runners behind me decided to stop early and accepted a ride to the finish line, I don’t think there were any actual injuries during the race.

I crossed the finish line at 4h-44m-44s. The guy with the stopwatch was actually amazed at the pattern of 4’s and showed the watch around to others, but after almost five hours of running through snow, I was a bit too dazed to do much but walk around in broad circles and stretch my muscles until one of the tundra trucks drove a group of us back to McMurdo. (Since I was dressed to run a marathon, I didn’t have as many layers as I usually wear and didn’t want to sit down in the snow where I would’ve gotten cold instantly.) Once back at McMurdo, I sat down with a group of runners and didn’t get back up for a few hours, but it was nice to chat with some of the folks who work at the station. Many of the runners had a bit of a ‘Clint Eastwood’ limp for the rest of the day, walking stiffly like a cowboy, but after icing my knee for a few hours I actually felt much better and wasn’t nearly as sore as many of the others. (I had also stayed VERY conscious of taking it easy during the race, since an injury could ruin the rest of my field season.)

And you know what? After nine days of waking up at 6am every morning to see if the daily weather assessment would allow helicopter flights back to my field site, on day 10, the day after the marathon, the weather cleared. Fifteen hours after I ran my first marathon and was completely exhausted, a helicopter dropped me off on top of Canada Glacier, where I spent a few hours snowshoeing across the ice with my gear and collecting water samples before scaling down the glacial wall to my camp. In a place like this, if you’re going to push yourself ‘for fun’ on a day off, you still need to conjure up the energy to get back to your usual physically-demanding job when the weather clears.

But hey, this is Antarctica… and it was never meant to be easy.

Reconnaissance for the Ionic Pulse

Dec 21, 2014

I’ve been at my fieldcamp next to Canada Glacier for a few weeks now, waiting for the melt season to start. And… it hasn’t. Every week I’ve been hiking up the mountainside and onto the top of Canada to look for surface melt, but the surface pools (see my blog post on surface pool cryoconites here) are still frozen over, even on warmer days. Last year there was far more melting at this point in the season, which has led a few people to ask me “So is this year colder? Does that mean climate change has stopped or isn’t real?”

Meltwater streaming through Canada Glacier in December 2013. In addition to the melt, ablation (evaporation of ice into air in very dry, sunny and cold climates) removes the snow first, then starts removing surface ice into the soft and ‘punchy’ (low-density) layers seen here.

The same location on Canada Glacier in December 2014. The surface ice is still very dense and slippery, with wisps of snow blowing across the glacier and no melt yet to be seen.

Not quite- this year isn’t actually any colder, it simply has far more intradial (‘within a day’) and transdiurnal (‘across a few days’) temperature variations than last year. In the summer time, temperatures in the Dry Valleys will fluctuate between well-below (-18C or 0F) to slightly above (3C or 37F) freezing. Last year these fluctuations tended to happen slowly, so that you’d have a few days of warmer weather, followed by a few days that were colder, then a few warmer again, slowly moving towards warmest days in early January but with a slight variation here and there. This year, instead of ‘multi-day’ weather patterns, we’ve been having ‘jumpier’ conditions where one day is very cold, then the next day is much warmer, then back to cold again. Overall if you were to compare the total number of ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ days between both summers the number would be the same, but the rapid speed of temperature jumps this year (rather than gradual changes like last season) has a few significant impacts on glacial melt and a process called the ‘ionic pulse’.

Renee offered to join me on a hike up the mountainside towards the ridgeline of Canada Glacier to check on the status of the melt in early December

When I tell people I work in Antarctica studying the deposition of pollutants into glacial melt, some people ask why I have to stay here for the whole summer season– instead of waiting around for the melt season each year, why can’t I just carve a block of ice out of a glacier, melt it in a lab, and study it there? Why spend my time living in a tent, collecting water at different times during the summer? The answer is that glaciers aren’t made of ‘pure’ water and don’t melt evenly; different components within the ice will melt at different times and the composition of meltwater itself will change throughout the summer.

Higher up the mountainside with the tongue (bottom ‘fan’) of Canada Glacier in the background, on a ‘reconnaissance trip’ to check the status of the glacial surface melt.

Like most natural water around the world, glacial ice has additional compounds dissolved within it such as sodium, calcium, potassium, chloride, sulfate, and carbonate. These solutes decrease the freezing temperature of water so that if pure ice melts at 0C (32F), the impurities in glacial ice might instead melt at -2C (28F). (In other words, you need colder temperatures to freeze impure water, and those impurities will also melt out sooner than pure water.) So as temperatures warm up during the summer, if the average temperature in early December is -2C and the average temperature in early January is +1C, this means the impurities within the glacier will start to melt out earlier in December, leaving ‘purer’ ice behind to melt in January. This is called the ‘ionic pulse’; an initial burst of solutes and nutrients that preferentially melt out of a glacier at the beginning of the melt season before the temperatures are warm enough for the cleaner ice to start melting. In other areas of the world like the Colorado Rockies, the same type of ionic pulse releases nutrients from snowmelt during early spring and has significant impacts on plants and organisms that rely on those compounds for growth. Each spring you can see a spike in the nutrient load (concentration of solutes in the water) in rivers and streams that are fed by glaciers or snowmelt. So for my research, I can’t just carve out a bit of ice and take it back to a lab to study it because the environmental conditions of Antarctica itself will affect which parts of the ice melt at different times, which in turn affects the chemistry and composition of the meltwater that I study.

There is still a lot of snow that hasn’t yet ablated from the surface of the glacier. Snow has a very high albedo (reflectivity to light) that prevents sunlight from penetrating down to the ice level beneath it, delaying the beginning of the melt season.

So even though I study glacial melt, I need to be here in the mountains BEFORE the initial ionic pulse of melting starts, in order to make sure I’m here when it happens and I don’t miss it. Then I’ll continue to take different samples during the whole season as the composition of the meltwater changes, to keep examining how atmospheric pollution reacts with and deposits into the different stages of melt. This year, though, the pulse hasn’t happened yet– we need to have a few nice, warmer days all in a row to get the process going. It’s like pushing a boulder down a hill- a few consistent shoves in the right direction will get the ball rolling and once that happens it will gain enough momentum that it can’t be stopped, and likewise a few warm days are enough to initiate glacial melt strong enough that the occasional colder day won’t stop it (until the end of the summer season when it is always below freezing again). Last year, we had a few warm days in a row that initiated that downhill ‘push’. This year, the cycle of ‘cold! warm! cold! warm!’ days hasn’t offered a long enough temperature consistency to start the process yet. And so I wait…

Trekking across a glacial surface of dense ice. When we finally do have a few consecutive days of warm weather, (hopefully soon!) the ionic pulse is going to surge quickly and start to melt out of the glacier like a sponge.

Brinicles Under the Sea Ice

Dec 11, 2014

When I was at McMurdo Station, I had the opportunity to visit the ‘Observation Tube’, which is a narrow tube drilled through the sea ice surrounding McMurdo Sound that leads to a small, windowed seat where you can take in the scenery beneath the sea ice. I took my GoPro camera into the tube with me and was able to hear the sounds of a few different seals making their surreal, ‘sci-fi’ sounding squeaks under the ocean, as well as get my first view of brinicles.

Brinicles are concentrated columns where extra-salted seawater sinks to the ocean floor. When ice freezes, the purer water freezes first and pushes saltier water away from the ice structure. As more and more fresh water freezes, the liquid remaining behind gets increasingly concentrated (as well as increasingly cold-while-not-frozen), and eventually this salty brine, which is denser than the surrounding fresh water, sinks towards the bottom. Since the brine is still very cold, though, the low temperature causes nearby freshwater to freeze around it as it sinks, creating a tunnel of freshwater ice surrounding the column of deepening salty brine. The brinicles were distinctly visible as ‘ice tubes’ underneath the sea ice in the video, and it was beautiful to sit in the Observation Tube and take in the 360 degree view beneath the ocean surface.

Check out the video below! I included a little video section of the hike towards the Ob-Tube across the ice simply to show a little more of what it looks like to hike around near McMurdo Station, but the dialogue between my friends and I isn’t important, it’s just part of my experience taking a trip under the ice. (*To read the text within the video, make sure your youtube settings are set to a quality of at least 320p. Most faster internet connection speeds will use HD quality (720p) anyway, but if the text is blurry, check this setting.)

The BBC series ‘Frozen Planet’ also has an amazing segment where they filmed an extreme time-lapse of the formation of brinicles under the ice, part of which is available here-

Not Your Typical Commute To Work

Dec 3, 2014

I’ve arrived at my fieldsite in the mountains! I had a great week visiting McMurdo station before arriving at my final destination at Canada Glacier in the Dry Valleys of the Transantarctic mountains. I had a few opportunities to explore the area around McMurdo Station before I left, including a trip to an underwater observation station underneath the sea ice, a trip out to the historic explorer’s hut out at Cape Evans, and my first Thanksgiving at an American Antarctic station. (Since all my previous Antarctic station experience has been working for the French, Italians, and Swedes who don’t celebrate Thanksgiving.) I’d like to write a few more articles about those later, (don’t I always tend to say that??) but in the mean time I wanted to show you all a video clip of my helicopter trip from McMurdo Station on Ross Island, across the Sound to mainland Antarctica, and into the Transantarctic mountain range. In the video you’ll notice that the first mountains we pass are still covered by part of the Antarctic ice sheet, but the second valley range is dry on the bottom- that’s why it’s called the Dry Valleys.

What I like about this video in particular is that it’s often difficult to show the proper sense of *scale* for the size of mountains and glaciers here- people see pictures like these two,

Canada Glacier spills down across the landscape in the upper left side of this photo of Taylor Valley, while my camp from 2013-14, F6, is labeled on the right of the photo

which are taken from quite high up in a helicopter, and the glaciers look smoothly sloped and not all that tall, even though their downslope edges (called a ‘glacial tongue, the part that sticks farthest out from a glacier’s uphill origin) are often more than forty feet tall. This is simply a problem because the valleys and mountains themselves are so BIG that when a camera is zoomed out or a helicopter is high in the air, the glaciers look smaller than they really are. For instance, here are a few different photos of Canada Glacier again (seen in the second photo above) with people or buildings that add a sense of proportional perspective-

Hiking towards Canada Glacier. The orange box in the photo is a gauge station used to measure streamflow, the same size as the gauge station in the picture below–

This is a similar view to that seen in the end of the video posted below. The tiny blue squares in the bottom left of the photo are the Lake Hoare laboratories, while tiny yellow specs on top of the ‘islands’ on the lake are scientists’ tents. My tent this year is slightly more uphill towards the mountains than this site. The glare in this photo is because it was also taken from a helicopter; the only way to get this sort of angle on the size of the glacier compared to the buildings below.

So it can be difficult to show both how WIDE the valleys are and how TALL the glaciers are within the same photograph, and that’s why I’m happy with this video below because it shows the valleys both from up high, and the eventual landing spot in front of Lake Hoare’s storage building (the green semi-circle dome at the end of the video) that gives the trip a sense of scale.

Filming in a helicopter without the permits to have ‘mounted cameras’ can be pretty bumpy, so I wrote a program *into* the camera before filming to try to anticipate the vibration and smooth out the video. It’s only effective when the helicopter maintains constant speed (so it doesn’t work during acceleration/ landings and during high wind interference, which you can see in the video) but for a back-of-the-envelope calculation made by a non-programmer with a borrowed GoPro living in a tent in Antarctica without proper video editing software, I’m pretty pleased with the results of this first attempt. I applied a second stabilizing program in post-production, but I still need to crop the video a little to remove the frame interference. (I don’t have a decent video-editing program for that, but I’d like to find one…)

It’s Nice Back on Ice!

November 19, 2014

I’ve arrived back in Antarctica! It’s nice to see familiar faces at McMurdo Station, where I’ll spend the next week prepping and packing my gear for life out in the field. If you’re new to this blog, check out this video from last year (Season 3) to see what it’s like to fly to Antarctica. This blog article, ‘Scaling Giants’ describes the research I do in the field and why I’m here for the season. If you’re interested in reading more about life at McMurdo Station (the main base of operations for Antarctic science, located on Ross Island next to the Antarctic continent) check out my article about the Station here, or the short video tours of station here. I never spend very much time at the main station but since it’s where the vast majority of scientists work and live, a lot of people are curious about what it’s like there.

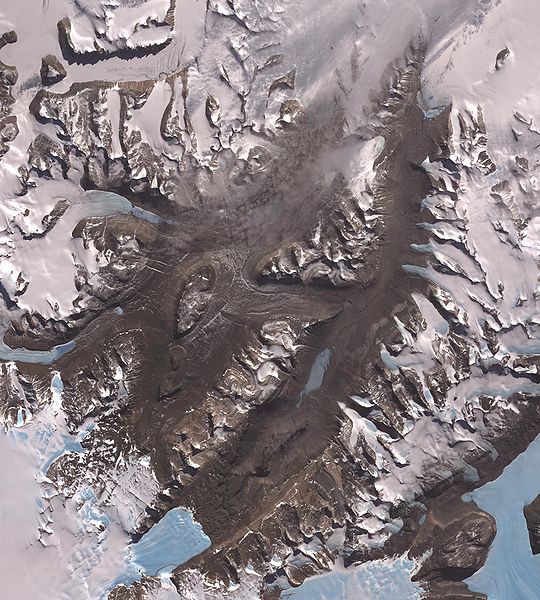

Despite the similar name, my field site in the ‘McMurdo Dry Valleys’ of the Transantarctic Mountain range is a completely different area from McMurdo Station and requires a helicopter to get out us out into the field across the sea ice from Ross Island to mainland Antarctica. The Dry Valleys are the largest ice-free area of Antarctica– approximately 97-98% of the continent is covered by the Antarctic Ice Sheet (which contains 70% of the planet’s fresh water as ice), while the Valleys consist of exposed earth and mountains mostly uncovered by ice, although there are plenty of glaciers between the mountains. The interesting thing about this area is that due to the ‘warmer’ temperatures that can rise above freezing during the austral summer months, seasonal rivers and streams are created by the glacial melt that run through the valleys and deposit meltwater into various lakes. Average temperatures in the Dry Valleys are approximately -20C (-5F) and the streams only flow when the weather is warm enough for glacial melt (0C or 32F), so from late November to the end of January (austral summer in Antarctica) when these temperatures are possible, water slowly melts out of the ice and I’ll be looking at the atmospheric contaminants that deposit into glacial melt here.

–

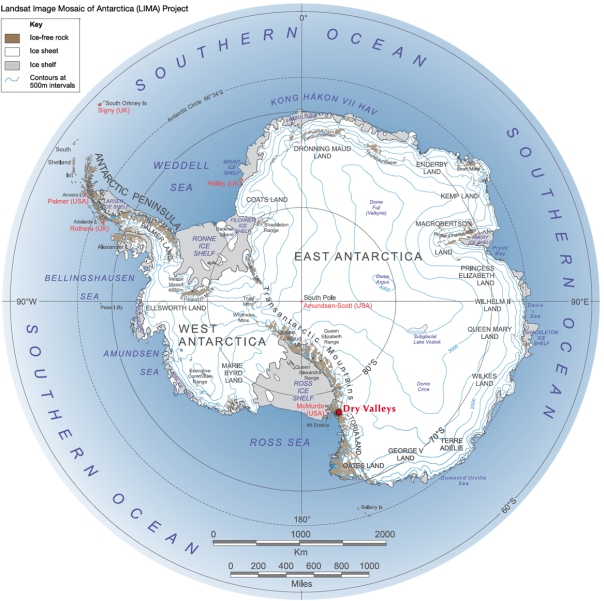

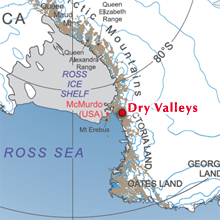

A map of Antarctica (courtesy of exploratorium.edu) marking the Dry Valleys withing the longer stretch of the Transantarctic Mountains that divide the West (left) and East (right) Antarctic Ice Sheets

Even though this looks close to McMurdo base, it’s actually about a 45 minute helicopter ride away. McMurdo is on Ross Island, while the Dry Valleys are on the continent of Antarctica.–

–

Glaciers pouring down into the Dry Valleys. Since this photo was taken from a helicopter it’s difficult to get a sense of scale, but most of these glaciers are more than forty feet thick at their downhill (thinnest) edge.

Since these mountains are farther away from the research stations, I’ll be living out of a tent at the base of Canada Glacier at a fieldsite called Lake Hoare, with 2-3 other people who will be working on other projects. I’ll arrive there next week but in the mean time I’m excited to spend Thanksgiving here at McMurdo Station, where there are currently 930 people living and working on base.

Season 4: The Beginning of the End

Nov. 8, 2014

After a few months of hectic and rushed fieldwork in different states, time zones, and continents, I’m getting ready for my fourth and possibly final season in Antarctica. It’s a strange feeling because I love working on this continent, but I have to remind myself that my work here is towards a degree (my PhD in environmental engineering), and I would like to graduate at some point soon, which unfortunately means I’ll have to face the reality of the adult world and ‘real’ jobs that don’t involve wearing a snowsuit and ski goggles to work. (But hey, if anyone out there is hiring a Transantarctic toxicologist, keep me in mind! 😉

This upcoming season, from mid-November to mid-February, will be unique in a few ways- I’m going to be working in the McMurdo Dry Valleys again like last year (Season 3) although at a different fieldcamp in the mountains, closer to the glaciers where I do my research. This is different because my first three seasons, on a Swedish Icebreaker, a French/ Italian Station on the High Plateau, and last year in the Dry Valleys were all so different from each other that I never had any idea what to pack. This year since I’ll be in the same general region as my beloved tent at F6 during 2013-14, it means that at least I have a good idea of what to bring without packing too much, and what sort of weather/ temperature conditions I can expect on the Ice. I’ll be living out of a tent again and working at a fieldcamp that has between one and four other people there, but my research examining global pollution deposition onto glaciers will be by myself. There is a policy in Antarctica that field scientists can’t live *completely* on their own; anyone who gets dropped off by a helicopter needs to be in a pair of at least two people for safety purposes, so since my work is by myself I’m living at a fieldcamp called Lake Hoare (named after Antarctic physicist Ray Hoare) with people conducting other research simply so that we’re (all 2-4 of us) together for meals, etc. It makes logistics like cooking, collecting glacial ice chunks to melt for drinking water, and charging our emergency radios with the solar panels we have all easier tasks when they’re split between a few people. I’ll find out more about the specific conditions of my life in the field once I arrive there next week, but in the mean time I wanted to update on the fact that I’m about to embark again on another season, hopefully with a lot of pictures and descriptions along the way, and I’m excited and a little bit nostalgic to be returning to Antarctica once again!

Season 3 Comes to an End

This post is a bit delayed, and because of an interesting story… it’s the adventures of my GoPro camera all around the world! During my 2013-14 Antarctic season, I took a bunch of video footage of various aspects of life in the field, and hoped to put that together into a series to show you guys back home. Unfortunately, when I shipped my equipment back to the US at the end of my season in February 2014 after the storms that delayed my departure, I mailed the GoPro back to my Colorado address but instead it decided to take a series of riveting detours through New Zealand, Hawaii, California, Florida, Washington DC, New York, and finally Colorado… in October 2014, nine months after I initially mailed it to myself. The one nice thing is that at least now I have it before I head back to Antarctica again this year, in precisely one week! So this season I’ll go through the videos I took last year and try to put something together (although it’s difficult to upload videos from the Ice) and see what I can show you from my third season. I should (hopefully) have somewhat more reliable internet during my 2014-15 year on the Ice, coming up quite shortly, so I’d like to be more thorough with this blog. (I also have more than 50 schools following along with my adventures this year, so I’ll try to answer questions as I can but it’s a lot of people to answer to!) In the mean time though, I’m excited to go through the pictures and video from my third season, since I kept promising to upload them during the last few months as I eagerly awaited my adventurous camera’s return.

My fourth season on the Ice should be from mid-November 2014 to mid-February 2015, and stay tuned for updates as I arrive next week!