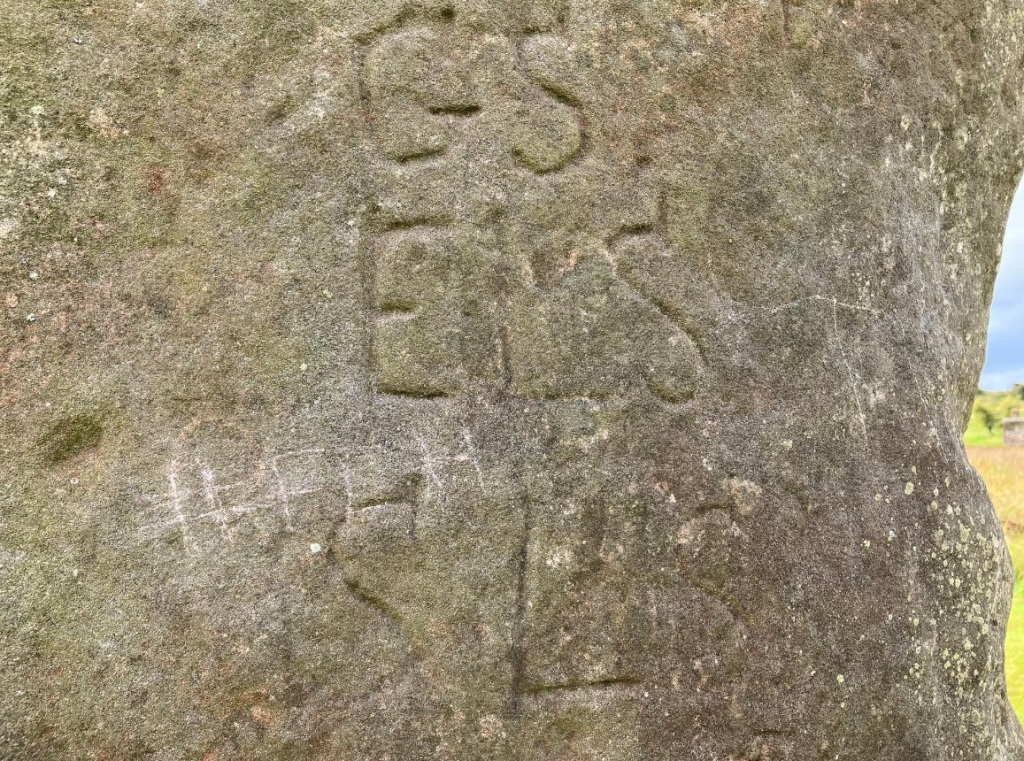

Graffiti has been on my mind a lot recently, prompted by a visit to Machrie Moor on the island of Arran in the summer where we noticed that one of the standing stones at circle 3 had been horribly defaced with a variety of very recent scrapings and markings.

The markings are a combination of scraped words including the F word, sketchy lines, and a hand-shaped zone where lichen seems to have been removed from the stone, perhaps using some sort of solvent or cleaning fluid.

This is as egregious an act of vandalism as I have seen at an ancient monument for some time, and literally a crime. It was also upsetting to see. This is now being investigated by Historic Environment Scotland, and a team have been at the site recently to undertake remediation work.

The tweet above shows recent graffiti at another site in Arran, the King’s Cave, a special place on the west coast of the island that is, ironically, defined by its carvings and graffiti from different eras.

This is not even the first time this has happened recently, with another example at Machrie documented and investigated in 2022. This may have been repaired but was the culprit ever caught? I doubt it or at least I have not heard of this happening.

A HES blog about heritage crime was in part prompted by an earlier incident at Machrie, and the carving of graffiti on one of the standing stones at the Ring of Brodgar on Orkney.

Repairs are all very well, but as HES stated in 2022, “Heritage crime can cause damage that can never be repaired and forces us to spend less resources on important conservation work.” In the aforementioned blog, they make the stark point: “Once the act is complete, the historic fabric is altered. In the case of incised graffiti, it will never be the same again”.

That was very much the case in a shocking prosecution in August 2023 prompted by permanent damage done to a Neolithic rock art panel on Eglwysilan Mountain in Caerphilly, South Wales. In this quite remarkable case, 52 year old Julian Baker had filmed himself for Facebook carrying out a crude excavation of this rock art site, which included damaging the site permanently.

The presence of the white and red ranging rod for scale here (and in other crime scene photo in this blog), so familiar from excavations, is used here to help to document a crime. In this case the rock art section of the panel was detached from the main outcrop. A CADW spokesperson said, “Significant archaeological information has been lost forever, and although some evidence may remain, the significance and value of the part of the monument damaged has been significantly diminished”. Mr Sands received a suspended jail sentence and was ordered to pay £4,400 in damages.

This had slightly uncomfortable echoes of some kind of unofficial excavation that had happened at Stronach Woods rock art panel on Arran when I visited with the Neolithic Studies Group in May 2023. I have no idea if this caused damage or not, but it could have. I reported this to HES and they are investigating.

Vandalism need not be in the form of carvings or crude excavations – take this spray painted standing stone, Maen Llia, in the Brecon Beacons from 2013. There are other examples if you have a google that are less amusing.

So many examples of what we must call the V word – vandalism – coming so close together has made me reflect on my own view of how we value and judge graffiti on prehistoric sites and monuments. Ironically, some of the most recent Machrie Moor graffiti overlies some rather more established carvings, date unknown but not recent. These have become part of the fabric of the monument and have not been erased. In fact, there are lots of examples of (neater) boilerplate Victorian writing on standing stones and megalithic tombs which have become part of the official story of the site e.g. Cuween chambered cairn on Orkney, Blackpark stone circle on Bute.

Graffiti of many types is a surprisingly common part of the fabric of prehistoric sites and monuments. The Ring of Brodgar and Maeshowe on Orkney were both covered in Viking scratchings, and indeed these are celebrated at the latter as a rare insight into informal Norse insults and ephemera. There are cases of modern vandalism of a standing stone carved with Viking Runes at Brodgar, in 2014 and 2015. At time of the latter, local media reported that, “An Orkney tour guide has spoken of his disgust at discovering one of the stones at the Ring of Brodgar has been vandalised this week, by someone scratching initials and a date on one of the stones, in an area close to where Viking runes are engraved”.

Disgust for the 2015 graffiti, celebration and preservation of graffiti carved on the same stones over 1000 years ago. This is not surprising. These Viking runes are significant heritage assets and have been and will continue to be studied; they are part of the historic significance of these Neolithic places, rich evidence of re-use, part of the monumental biography. They were not criminal acts at the time they were carved, although we have no sense of what social conventions were or were not followed at such megalithic sites in Norse times. Taking the act itself, they may have been illicit, taboo, or perhaps no-one cared or noticed.

On the other hand the carvings from last week or five years ago have no particular cultural or social value to us, and as such are in the wrong place at the wrong time. They are the outcome of illegal and illicit acts. I suppose were this to be 500 years in the future, then the initials of some drunk toe-rag carved onto a standing stone might provoke a different response although the long-term cultural significance of HFCH or FUCK is not clear to me.

Recent acts of vandalism at heritage sites can be complex. The repeated repainting of the Cofiwch Dryweryn (‘Remember Tryweryn’) on the wall of a ruined cottage is a case in point. This memorial was first painted in the 1960s to mark the flooding of a village by a reservoir in the Tryweryn valley in north Wales. The wall has been repainted many times, but also defaced, and has become a contested place that some want to preserve and others want to change. In recent years this mural has been defaced with Elvis (in 2019) and a swastika and white power symbol in 2020 amongst other things.

This is a serious business and here graffiti has become entangled with various different iterations of nationalisms, acts of subversion, and abuse. You can read more about this from archaeologists such as David Howell (chapter in this book) and Howard Williams.

Just this very morning as I write this post, I have been following twitter reaction to the illicit painting of a huge saltire flag on a wall on Cramond Island, near Edinburgh. As archaeologist Gordon Barclay has rightly pointed out, this is a heritage crime.

Many of the responses to this have been couched in nationalist terms downplaying the historic significance of the building that has been defaced. But as Gordon has argued, to what extent does the type of flag painted here cause some to excuse this crime or downplay the heritage value of this place? The V word is very much in the eye of the beholder.

This is illustrated by ongoing discourse about graffiti and damage to ULEZ cameras in London too – vandalism or a legitimate reaction to a political decision? How would the same fringe politicians and right-wing commentators who champion such costly actions react to the carved FUCK on a standing stone? We know how they respond to orange paint being thrown on the window of a bank headquarters. It is clear that the label vandalism is applied to any damage where you disapprove or disagree with the motivation of the perpetrator, which it not necessarily aligned with the law of the land.

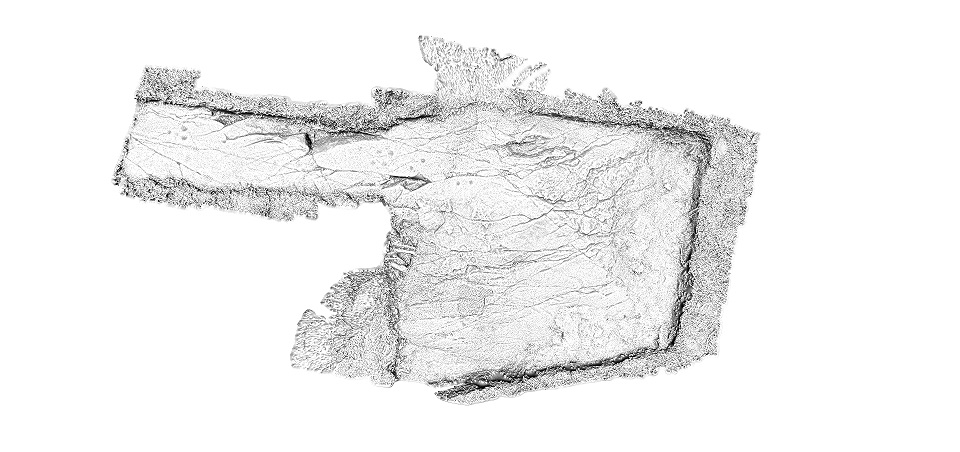

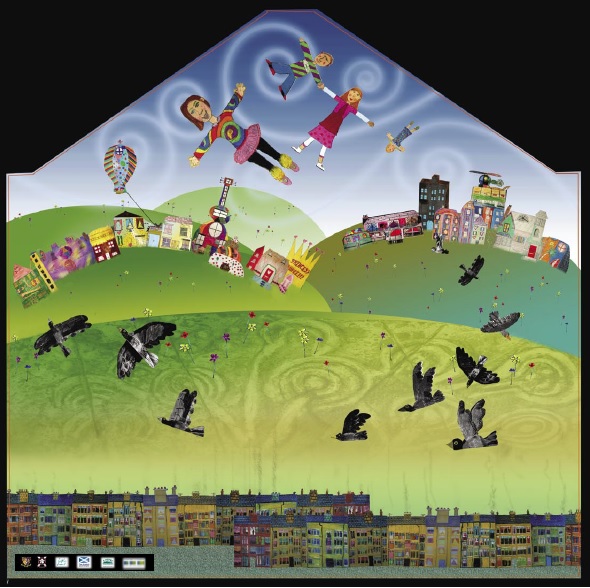

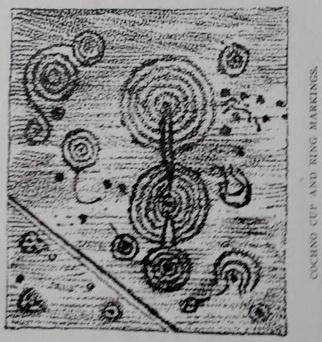

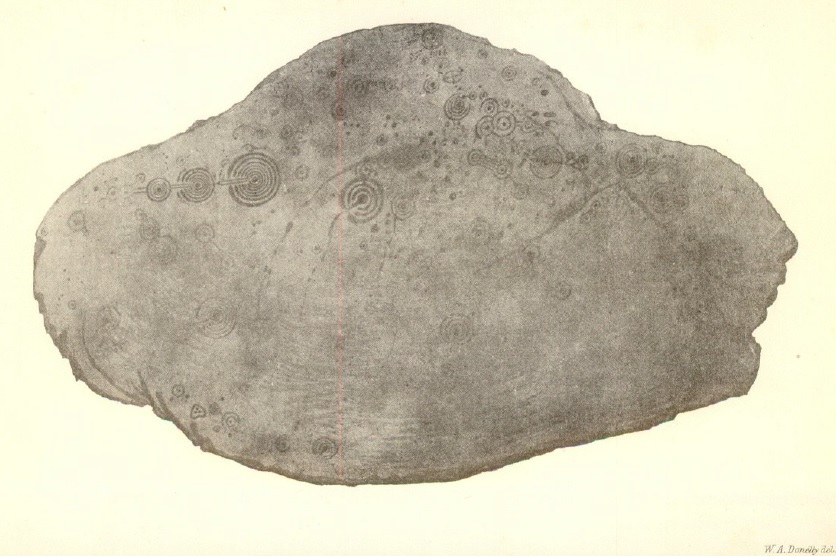

Perhaps where all of this hits home hardest for me is in relation to my own research into the Cochno Stone. In public lectures on this huge rock art panel in West Dunbartonshire I have called this site ‘the most vandalised prehistoric monument in Europe’.

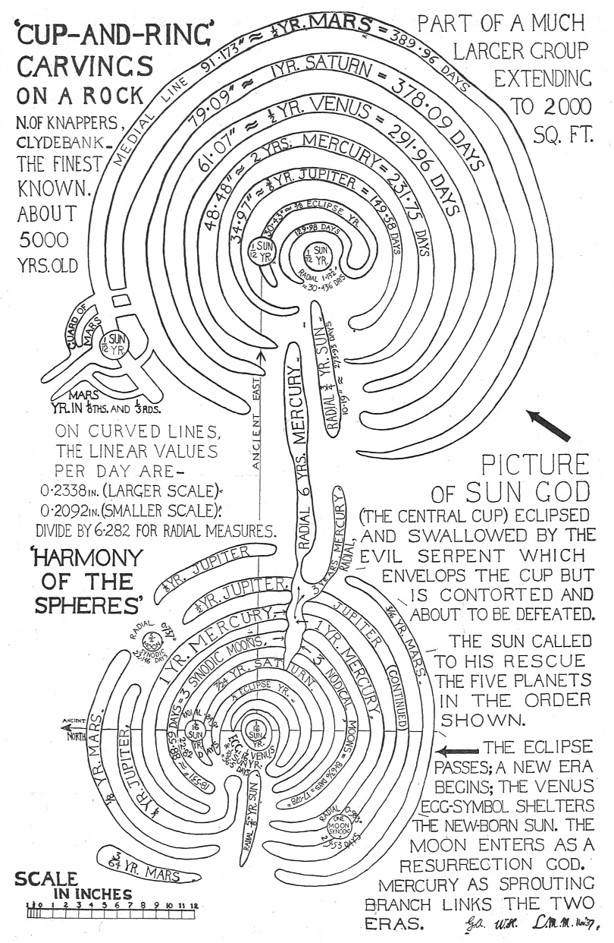

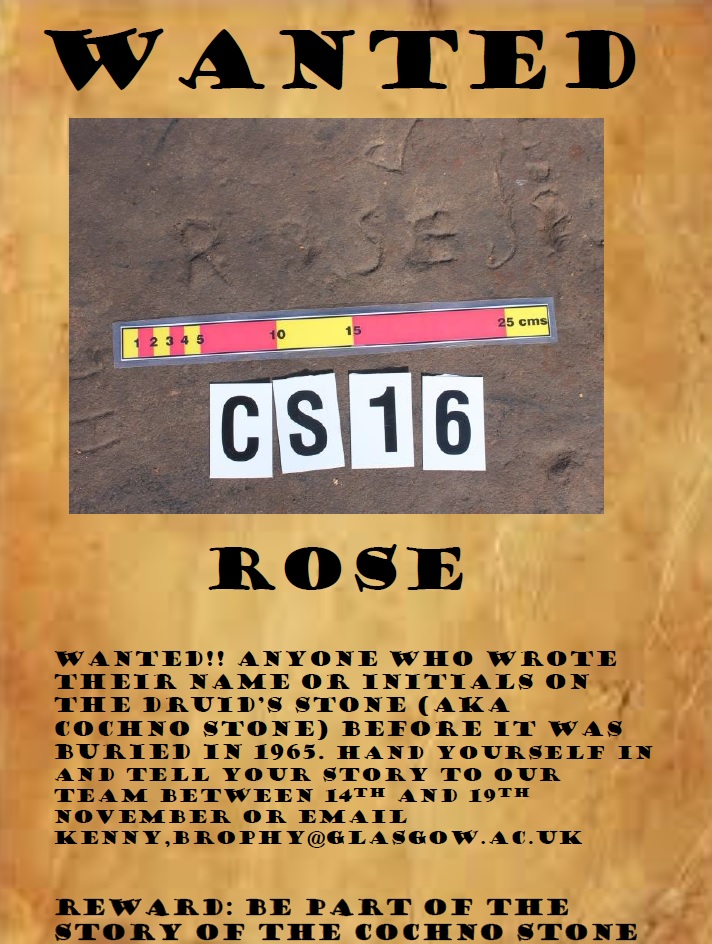

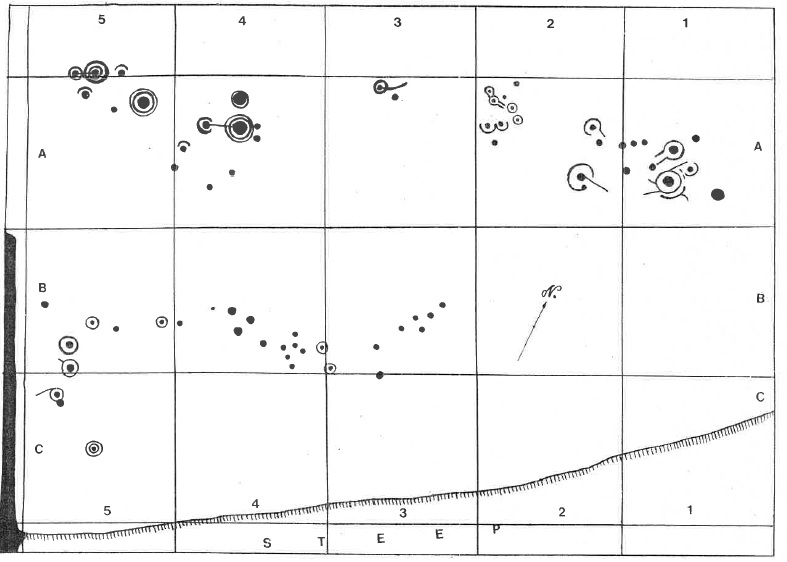

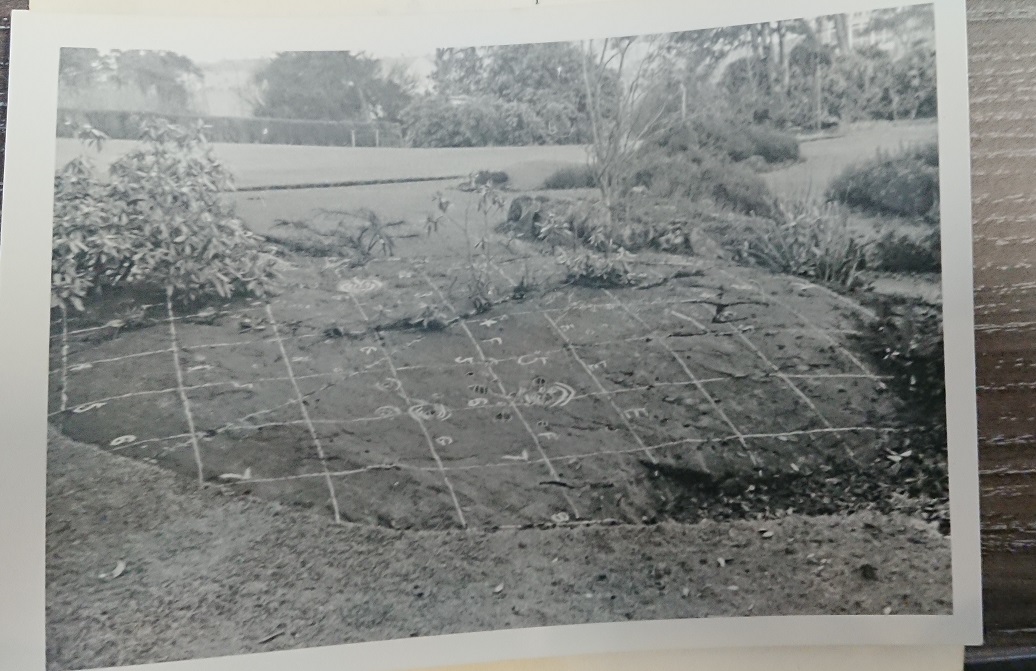

The story may be familiar to some readers. This Neolithic site became something of a tourist attraction after Ludovic McLellan Mann painted the surface of the stone with oil paints in 1937. The prehistoric symbols (and natural marks) were painted white and green, and Mann covered the stone with an elaborate yellow, blue and red grid based on megalithic measurements and cosmological tales of his own devising. This led to the site being scheduled — given legal protection — immediately. However, as more and more visitors came to the site, and urbanisation brought big populations to the area, so the Cochno Stone became an increasing focus for new markings – graffiti – with names, initials and dates scraped onto the surface of the stone. After decades of trying to manage the site, finally it was decided to bury the stone for its protection without any consultation or warning in Spring 1965 on the order of the Ancient Monuments Board (these are my words but taken from this source, yes I am plagiarising myself!).

So this is a site that in the 20th century was covered in oil paints by Mann in 1937 and some 100 piece of graffiti that only ended in 1965 with the burial of the stone. What Mann did was deeply eccentric and probably rooted in his own campaign for respectability. But it was not illegal even if he should have know better. However after the monument was scheduled in 1937 each act of graffiti was a heritage crime in the true legal sense even although my research suggests that many of the culprits were children, and the community had little sense of how significant or old this site was.

Alison Douglas’s research into the graffiti shows it to be a mixture of initials, names and occasional doodles, of a type that I am comfortable as being viewed as engagements with a place that had a special meaning for a local community. Yet is is also true that we found evidence of other less excusable damage such as remnants of a plastic bag or bucket that was been burned and melted onto the stone, and scuffs from folk walking across the stone constantly.

And during the 2016 excavation, one new piece of graffiti was added to the stone. Another heritage crime but one that I did not report or think much about at the time. Would I act differently now? Possibly.

What is the material difference between the 2016 graffiti and a similar set of initials from 1964? Why do I treat the graffiti and paint across the Cochno Stone differently from more recent examples that I have found upsetting? Rock art and the making of marks on stone seems to be especially vulnerable to such modern additions. It is a human desire but is it wrong? In some cases, legally and morally, yes. But not all.

I have been treating the Cochno Stone graffiti as if it were Viking Runes in Maeshowe. A cultural tradition that tells us something about a human engagement with an ancient megalith in a very specific place and time that is not now. The motivations for carving on these Neolithic stones were not especially noble – names, dates, doodles, indicative of casual interactions and not grand statements. But unlike the vandalism that this blog post was prompted by, my sense is that the carvers of initials and runes did not have the same motivations as the person who scraped the F word into a Machrie Moor stone.

I had something of as revelation as the graffiti was revealed – I wasn’t angry or upset Rather I was curious. HES historic graffiti expert Alex Hale has captured this feeling well:

“at some point graffiti emerged as a suitable subject to most of us and we realised that this unknown, potentially unruly, or even feral phenomena could open up new research possibilities—including those beyond the academy” (Hale 2022).

So when I started to try to make sense of the graffiti at Cochno, I was careful never to call if vandalism, instead using the term ‘historic graffiti’. I have never been judgemental and have spoken to some adults who carved their initials onto the stone when they were kids. I have tried to be playful about this such as the poster above (something that never saw the light of day as far as I can recall). But I accept that not everyone will see it like that.

There is no temporal cut-off point for when vandalism becomes historic graffiti. Nor should there be. Creative interventions and subversions can be legitimate and illegal at the same time. But we also have to acknowledge that graffiti and the like can be used by bad actors for political, nationalistic and sinister reasons. Some of this might be called ‘mindless’ as is likely how we would characterise damage at Machrie, but this is not always the case. For some, the motivation does matter. Rather amusingly Ludovic Mann went to the media in the late 1930s to complain about vandals throwing red paint over a cup-marked outcrop neat the Cochno Stone; this could charitably be described as mental gymnastics.

Proactively having a motivation to damage a prehistoric monument is not a get out of jail free card. Think about this Extinction Rebellion logo sprayed onto an interior orthostat at West Kennet long barrow in 2019. The world is burning so does anything go? The local ER Group coordinator Bill Janson does not think so: “We heard from the police that someone had sprayed our symbol on the stones, we were horrified and concerned. This act is completely against our principles”.

Graffiti and the vandalism of heritage sites is a can or worms because sometimes graffiti can be the heritage, but sometimes it is a heritage crime. This is not always as clear-cut as one might imagine. My own research at Cochno straddles this boundary and so it does no harm to reflect on the words I use and consider alternative views. The F word is almost certainly the V word – but beyond that things can become complicated.

Sources and acknowledgements: thanks to Alison Douglas for her work on the Cochno Stone graffiti and community members I spoke to and thanks also to Alex Hale for many conversations about historic graffiti over the years.

The Hale quote comes from a conference presentation he gave in 2022 entitled Graffiti Some Times: Archaeology, Artefacts and Archives – download.

To find out about Mann’s paintjob at Cochno 1937 see K Brophy 2000 The Ludovic technique: the painting of the Cochno Stone, West Dunbartonshire. Scottish Archaeological Journal 42 [contact me if you want a pdf of this article]

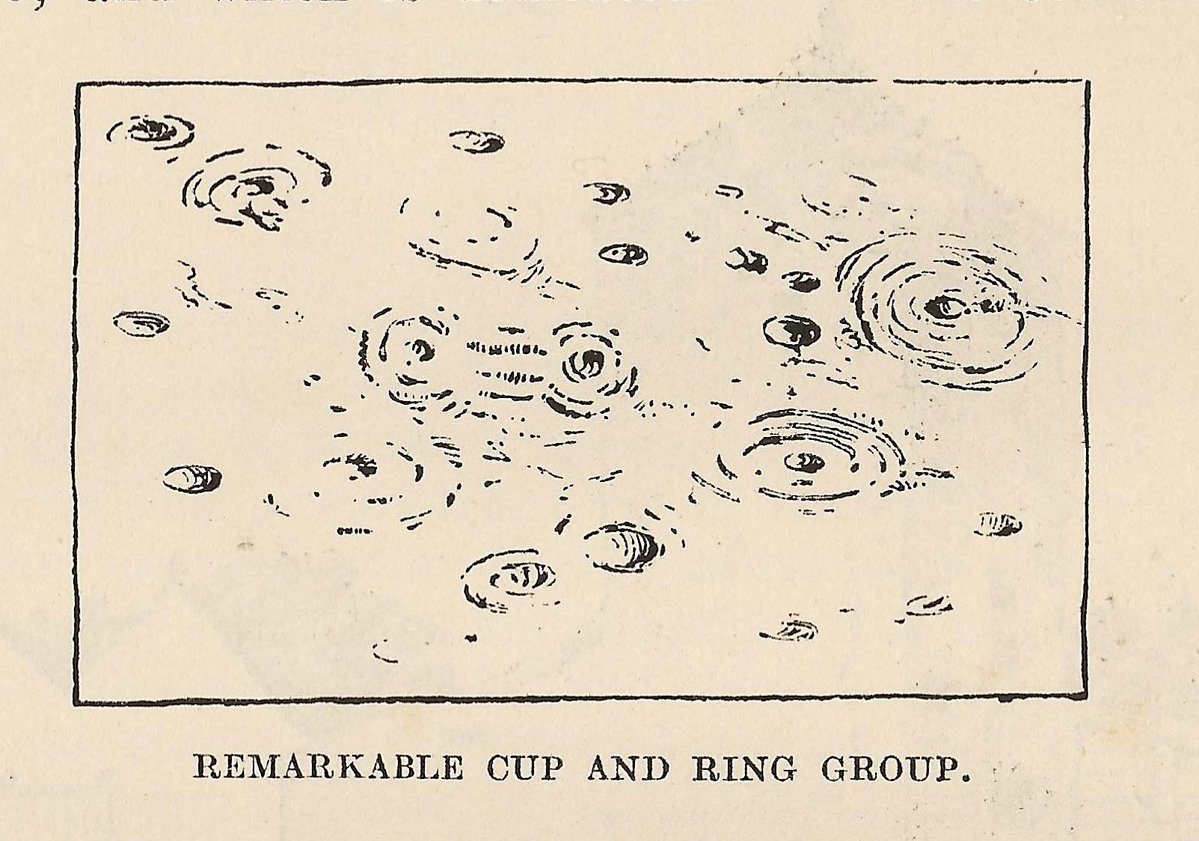

Source: Bradley et at 2019

Source: Bradley et at 2019

(c) HES

(c) HES