Following on from a recent post, Flint Head, this is the landscape from The Grey Mare and Her Colts, from which I found and carried the anthropomorphic flint back home.

In this picture, you’re looking west towards Golden Cap, the Blackdown Hills and over towards Dartmoor. The Western Lands. Peninsula airs.

And to accompany it, a short piece of prose on that part of the county of Dorset, travelling from Hardy’s Monument down to the Valley of Stones and the nearby Kingston Russell Stone Circle, another beauty of the British neolithic.

Landscape with White Horse

We’d driven up to Hardy’s monument. Not the writer Thomas, but Thomas the seaman who cradled Nelson as he died at Trafalgar. The wind is as big as the view from here, plunging away on all sides and playing in epic scales.

There was an old green bus parked up by the monument, a vehicle driven out of the Peace Convoys of the New Age, travellers who wound their way to Stonehenge for the summer solstice. The side of the bus was opened up, facing the coast, and a mother and daughter served tea and apple cake. ‘We’ve been travelling for a long time,’ said the mother. ‘We’re settled near here.’

She had a son, too, ‘a very good singer,’ said the daughter. She was slender, freckled, pale and pretty, a face like a mask, and she let the mask slip, an old god with a shining young face. I asked about the local music. There were local pubs that held monthly sessions. ‘We’re going to have a festival up here,’ said the daughter. She sounded defiant, looked it too.

‘Here?’ It was fabulous, an out of the way spot, but not for a gathering. The cloud shadows and gusty sunlight kept playing out its permutations over the waters of the channel and when we drove on the sky was clearing from the west. A clear day ahead, and a view of the western lands.

The landscape beyond here rose and fell between two great old roads through which your journey could sink down to the prehistoric level. Roads cut on foot, before horsemanship. One man and his gods and his charms – now in the local museum – terrifying big-cunted women, heavy chalk cock and balls, antlers, cattle bones, the long bones of his ancestors, finger bones, the right kinds of woods. The A303 and the A35 meet near Honiton, near the River Axe. These were old antennae of the body mythic.

We’d crossed over the A35 and were heading into the backwoods. The fork in the road came just below the brow of the hill, one way crossing the south eastern slopes of the Valley of Stones, the other reeling like a bobbin of cotton around the villages near Bridport. Not many cars came this way. Grass grew down the middle of narrow lanes that twisted and turned on themselves like stories from myth.

The Valley of Stones sounds like a Tolkein invention, but you’ll find it on any Ordnance Survey map. It takes its name from the clitter of conglomerate megaliths scattered across the hillside and down the valley bottom. It’s possible some organising agency may have taken hold of the Neolithic ritualists, for some see an arrangement of stones here. I could see nothing more deliberate than the scattering of Dorset Black Face across the higher slopes. It isn’t arable country here, but pastoral land for grazing. The air hums with insects and pollen, a skylark sings at different stations of the air above the long meadow grasses where it keeps its nest, the troubling young. The song is beautiful, and can’t be heard fully without the accompanying senses, pressed upon by the heavy heads of cow parsley, flashes of sunlight through the thick and twisted hedgerow, which is what Walton wrote into his music. You notice the hedgerow colours – green and blue and russet. Then a gateway of dried mud and a great circle of cattle faeces, across a field of grass your shadow advances upon you.

‘Dad did some paintings here,’ says John, leaning at the gate, sweat on his brow from the afternoon heat, and out of breath, full of time. What Dad did. An antique sign that had toppled over into the undergrowth announced our destination. Kingston Russell stone circle. My daughter clambered over the gate ahead of us and plunged into the long grass. John pulled it open and we walked through. Looking around, you could see why the spot had been chosen. Five paths met at just this point, walked out of the countryside by generations of feet. Pilgrimage, cattle drive, border march, festival?

Nearby, the Grey Mare and her Colts is an exposed, denuded burial chamber of sarsen stones from the mobile, pastoral Neolithic, a giant stone’s throw from here, down the hill towards Little Bredy, West Bay, the Jurassic coast and middens of shellfish. The three sarsens lean against one another like the fates, dried and haunted undersea conglomerate of the same geology as the stones here, 13 of them in a perfect circle, recumbent on grazing land. You could smell the fecundity. Sumer is a cumin in. I watched my daughter jump sunwise from one to another until she’d completed her circle, and I gave her a carton of apple juice. Someone had dressed one of the stones with a leather string through a hagstone, tied with a little bow of red silk. Done a careful job. The distances piled up from here, the skylark sang again. Bird music, mouth music, the wind in the high trees, through stones and walls and boughs. First music.

The oldest music written down comes from Sumer, a Hurrian hymn in cuneiform on a clay tablet from 1400BC, from the city of Ugarit, an ancient port town in northern Syria. We now know it as Homs. The hymn is to Nikkal, a goddess of orchards, a wife of the moon god. The Hurrians came from Anatolia, home to the oldest settlements in the world. Gobekle Tepe, ‘navel of the world’, was uncovered here by a German archaeologist in 1994. The previous expedition, an American crew, had mistaken the tops of the T-shaped stones for medieval graves. It is a temple complex, stones carved with an animal bestiary, dating to around 10,000BC. The last of the cave art was only a thousand years older. The complex was deliberately buried around 2,000 years later under thousands of tonnes of earth, around the same time the first root sounds of the European tongue are said to have emerged. Expert etymologies.

When this hymn was written down, its culture and place in history was already coming to an end. The music may have been thousands of years old, even then. Lend an ear, and feel your mind bend at the strain of a half-familiar tune, like the taste of the first domesticated wheat. The music has the quarter tones of the future, and the group chant, the weight of the past. It has been reconstructed as music for voices – the voices of men – and for the nine strings of the ancient lyre. Stringed instruments were old but the world’s oldest known instrument, apart from the hands and mouth, was the hollowed out bone of a cave bear, finger holes matching the inscrutable habits of harmony embedded in homo sap like a fossilised bear’s tooth lodged in the crevice of a cave painting. Singing do re mi through eternity.

The three of us sat on the stones for a while, absorbing the landscape as if it was freshly made, still wet, and we were taking in its colours like blotting paper. Down below was Little Bredy, the name an old word for broiling water – spring itself. Just beyond the village and in view still of its steeple, the descendents of Auroch cattle a Falklands War veteran had bred back out of the cave wall and into the Dorsetshire meadows. Long Horn breed, moving at the pace of epic timescales, tectonics churning in the mouth and cud. The most expensive meat in the farmers’ market.

We sat and listened to the skylark, the subtle tones of fields under a sky cleared of traffic. Pointing to the north, I told my daughter to scour the sky beyond the hills for the indigo pall of the Icelandic volcano. “There it is Daddy!” Not a plane in the sky…

Crammed in the car, doubling back to the forked road under Hardy’s Monument, and taking the little lane that unwound north of the Valley of Stones, into woodland spreading out from the valley floor. Ash, oak, thorn, birch, pine. Beech cathedrals vaulting over the road, the Dreamachine flicker of sunlight and shade. I can remember on the first long slow curve of the road out of the valley spotting a white horse standing in a dappled glade on the edge of woodland. And beyond that, a white caravan parked up at the edge of the greenwood, barely any traffic on this grassy byway. A black-haired man, very white skinned, naked to the waist, stepped from the van into the sun. He saw us, but he saw through us, we were chimeras from a later time, and not wholly part of his world, or of the white unsaddled horse in the sunlit glade of the deep wood, where the land folds in on itself and hides away.

Below, the original field drawing from The Mare.

Field work: Looking west from the Grey Mare and Her Colts

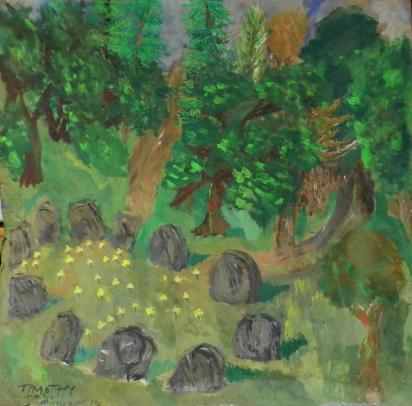

On a final note, preoccupation with prehistory and stone circles

goes back a long way in my book of life. This is an imagined picture from 1974,

with poster paints on cardboard.