Taenia species

The cestode genus Taenia includes several species that as adults live in the small intestine of dogs and/or cats and free-ranging carnivores around the world.

Summary

The cestode genus Taenia includes manyspecies that cycle between predator-prey assemblages around the world. Adult cestodes live in the small intestine of dogs, cats, and free-ranging carnivores around the world. Examples include T. hydatigena and T. pisiformis in dogs and T. taeniaeformis in cats. All species have indirect life cycles that require a mammalian intermediate host, which becomes infected by consumption of immediately infective, environmentally resistant eggs passed in the feces of the carnivore definitive host. Each species of Taenia has a characteristic larval stage (metacestode) that develops in the tissues or organs of the intermediate host. In Canada, the most common form is the cysticercus. Carnivores become infected when they consume the metacestode stage inside an intermediate host (through predation or scavenging). Adult Taenia are usually non-pathogenic, but some larval stages in the intermediate hosts can be associated with significant pathology. Diagnosis relies on detection of taeniid eggs on fecal flotation (or preferably sedimentation), or segments passed in feces. Since methods based on recovery of eggs from feces have poor sensitivity, and taeniid eggs cannot be identified to genus level based on morphology alone, PCR based methods are often preferable for diagnosis in dogs, allowing differentiation of Taenia from Echinococcus spp. There are many products labeled for Taenia spp. in dogs and cats, usually based on praziquantel. Control relies on preventing dogs and cats from accessing carcasses of infected wildlife or domestic livestock serving as intermediate hosts. None of the species of Taenia infecting dogs in Canada are zoonotic.

Taxonomy

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Cestoda

Order: Cyclophyllida

Family: Taeniidae

The Order Cyclophyllida includes several families that contain virtually all tapeworms of domestic animals and birds. Adults of most genera within the family Taeniidae are parasites of carnivores and omnivores, and have many morphological and biological similarities. Other tapeworms of veterinary importance - Diphyllobothrium (Dibothriocephalus) and Spirometra are classified in another Order, the Pseudophyllida.

All cyclophyllid tapeworms have basically similar structures and life cycles, although the details differ. Similarities among the genera within a cyclophyllid family are greater than those between families.

Taeniid cestodes include many different species of Taenia and several species of Echinococcus. These species circulate in fairly specific host assemblages and produce morphologically indistinguishable eggs.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016.

Morphology

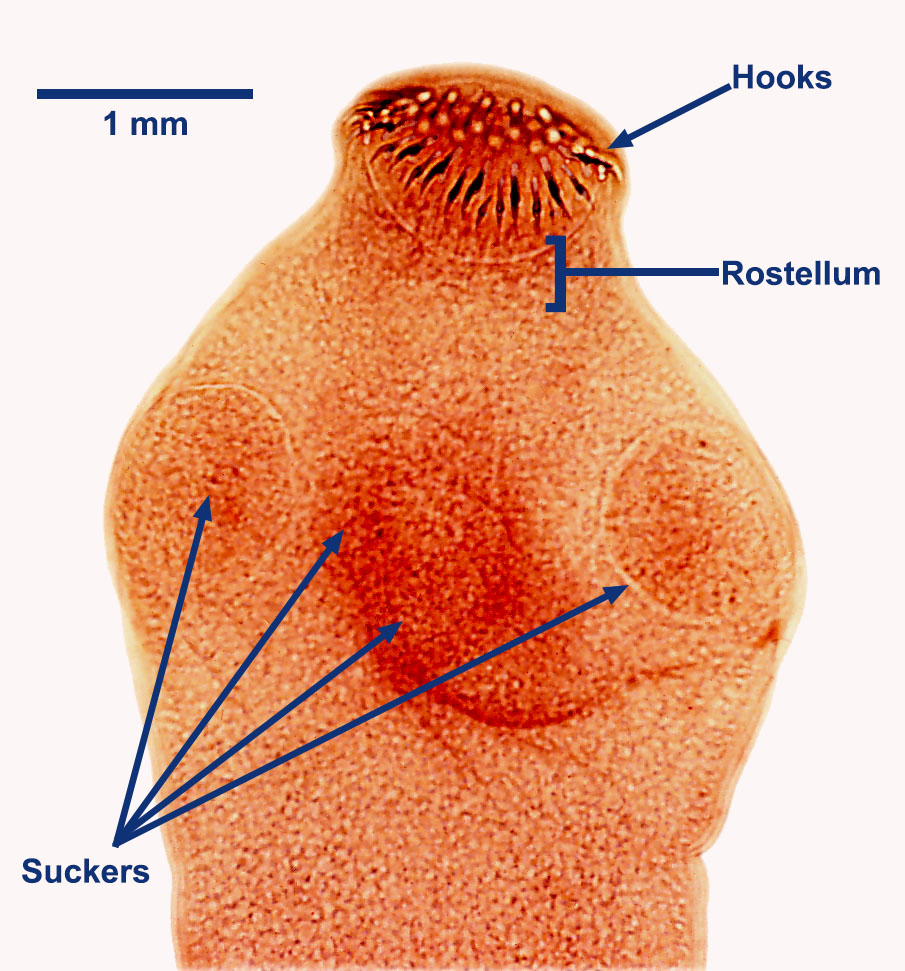

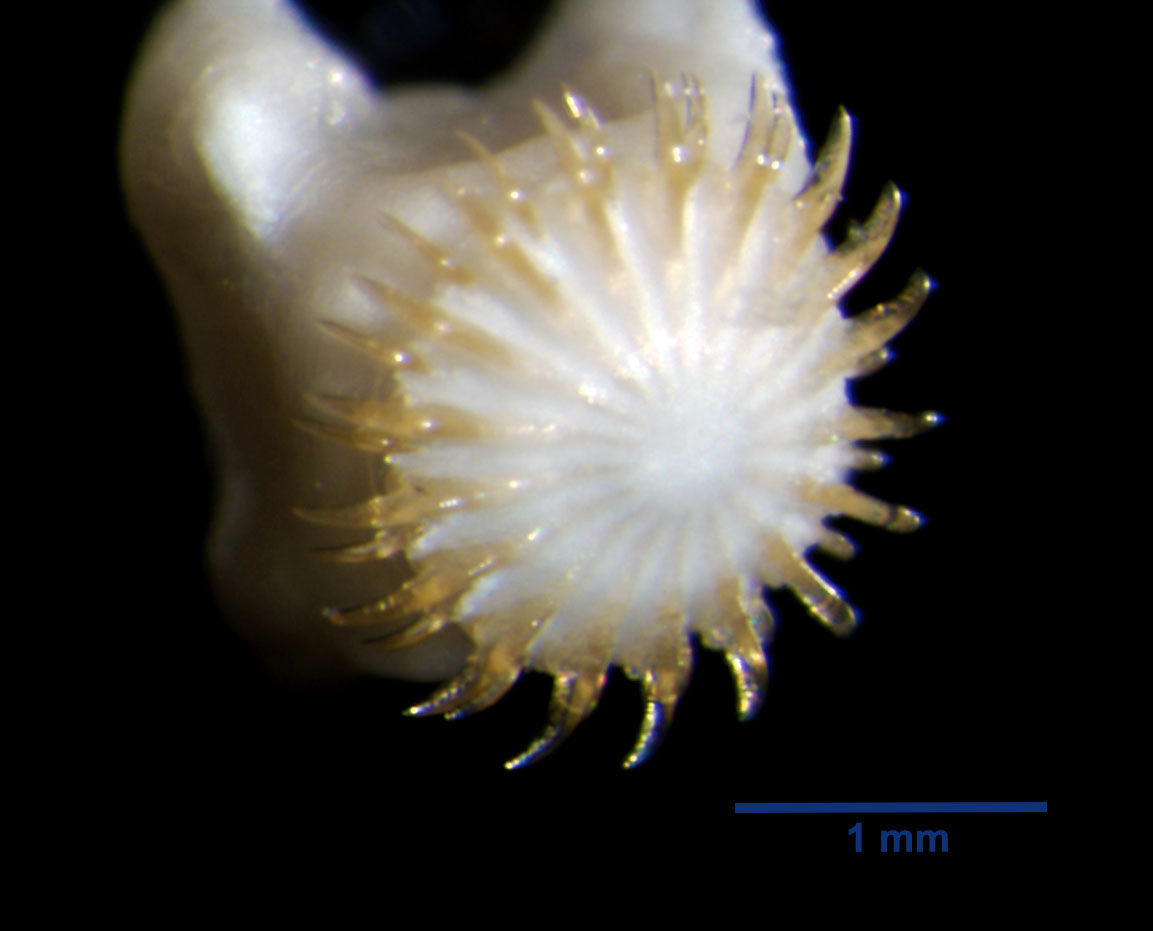

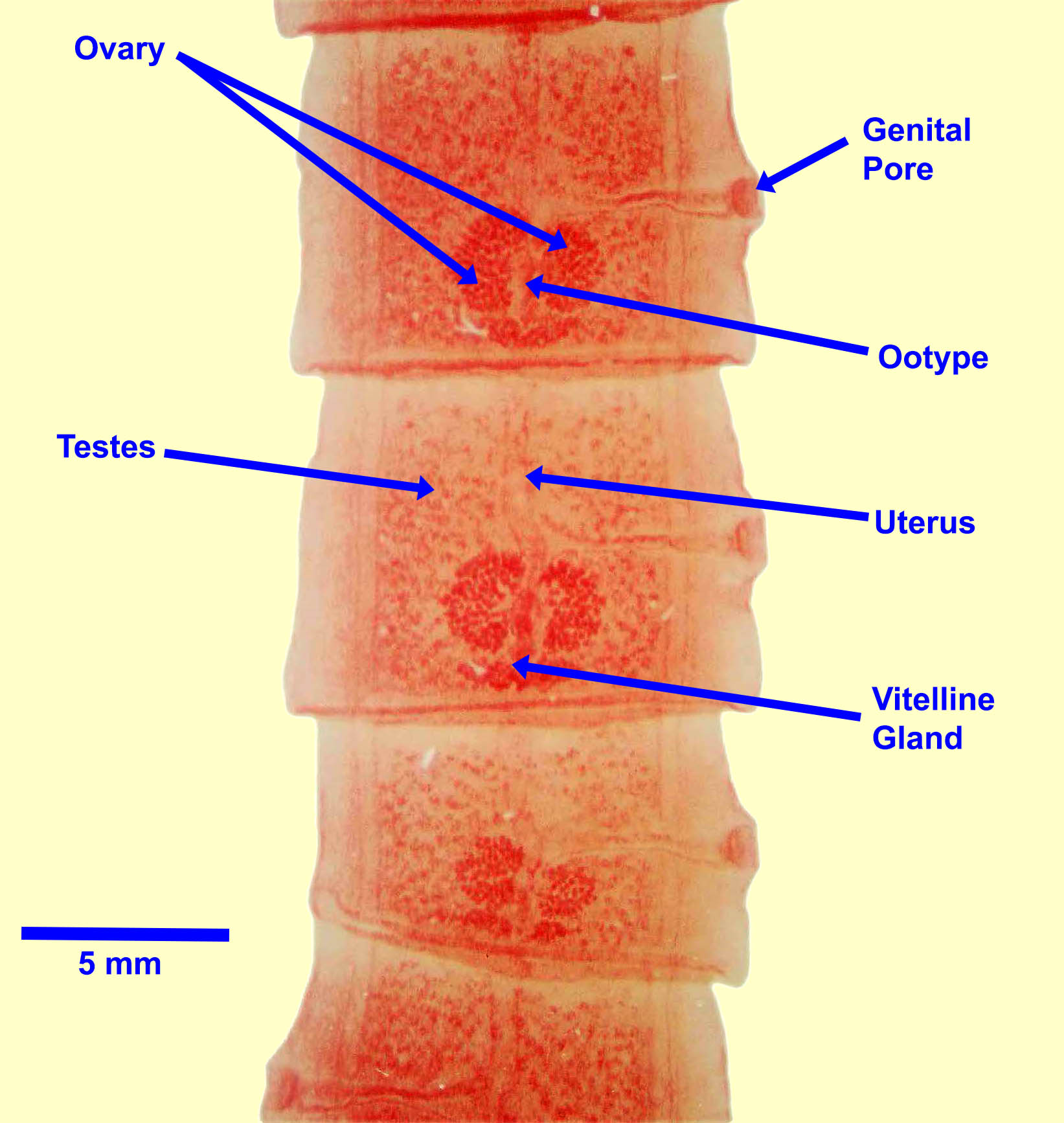

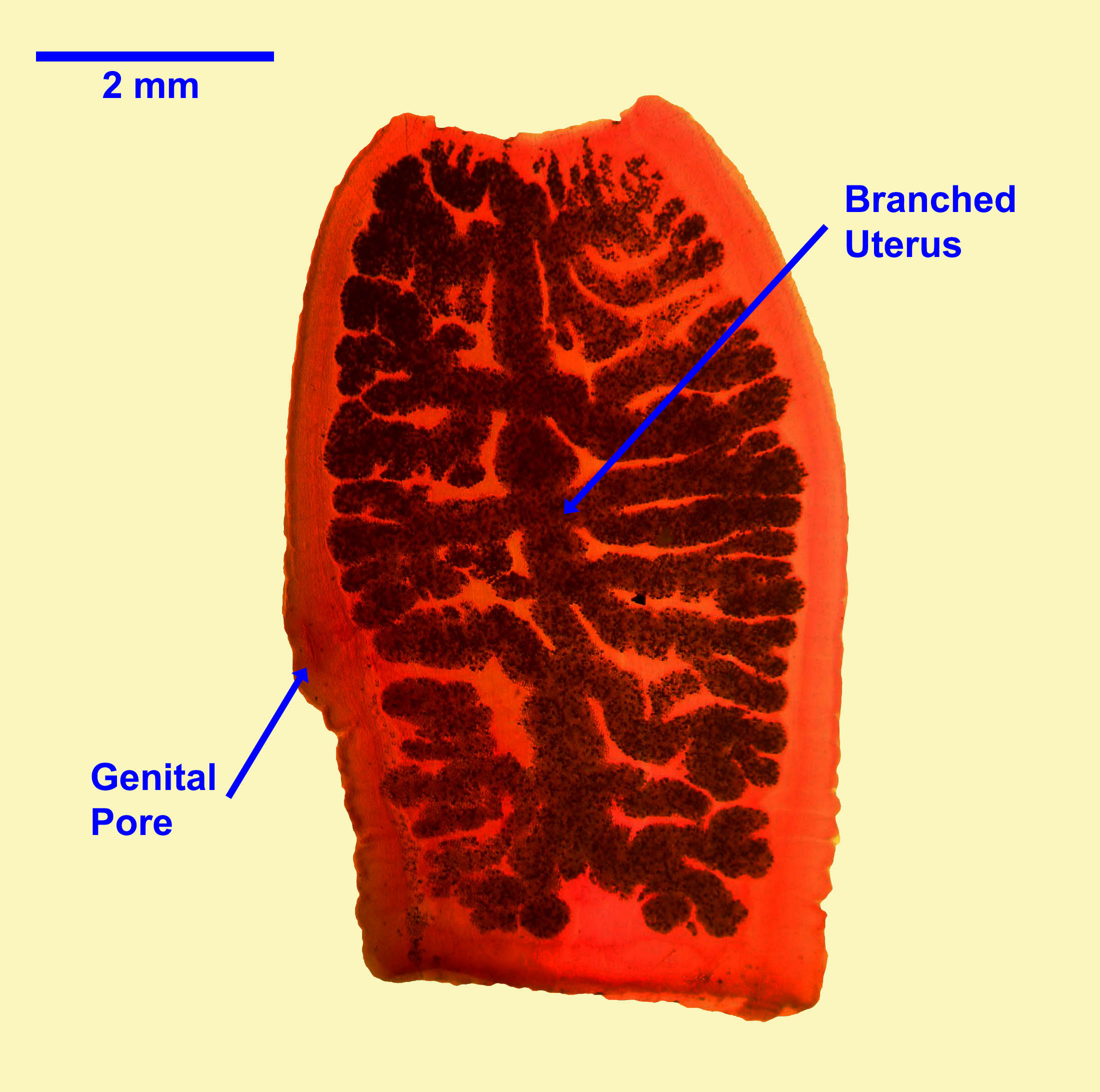

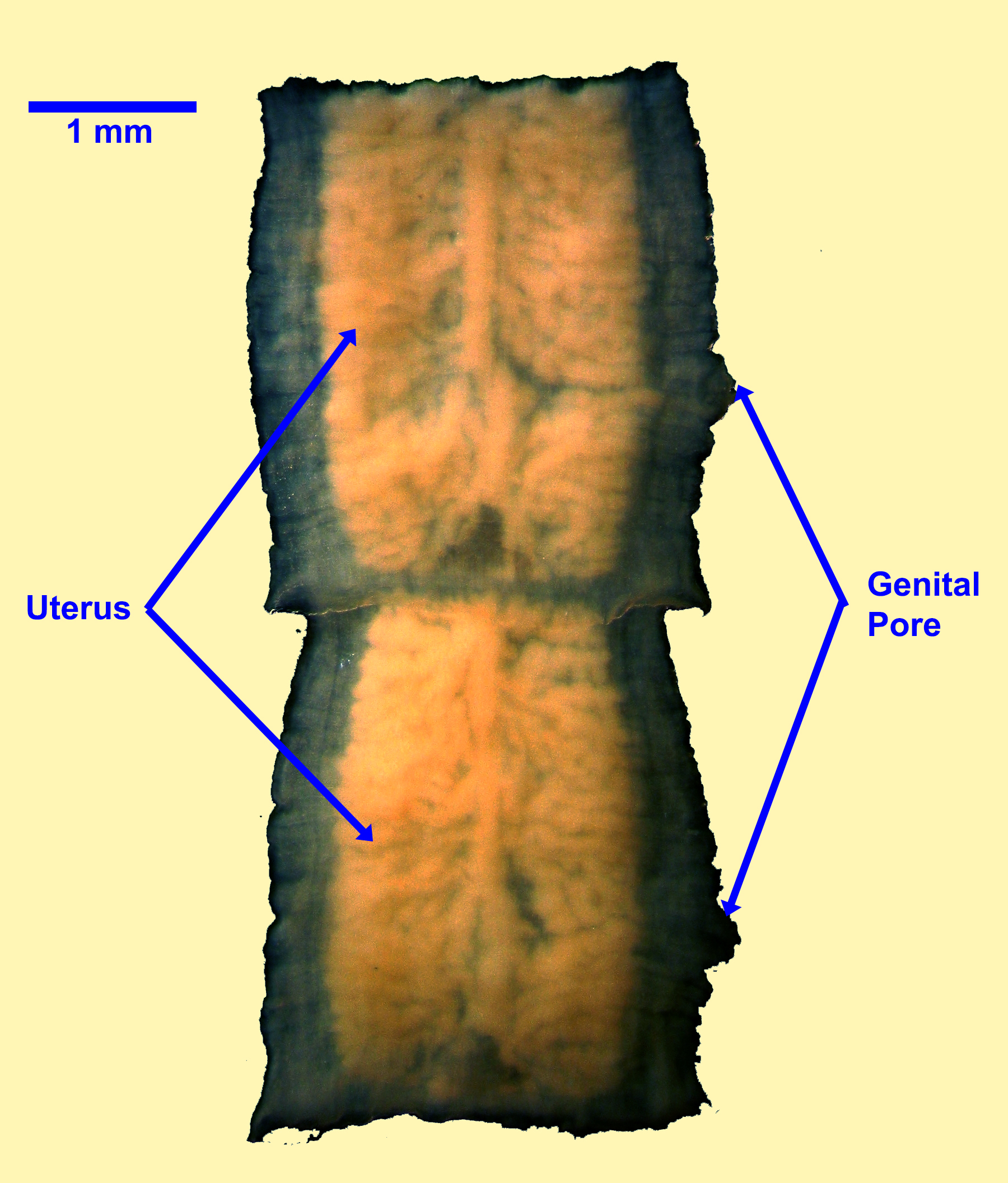

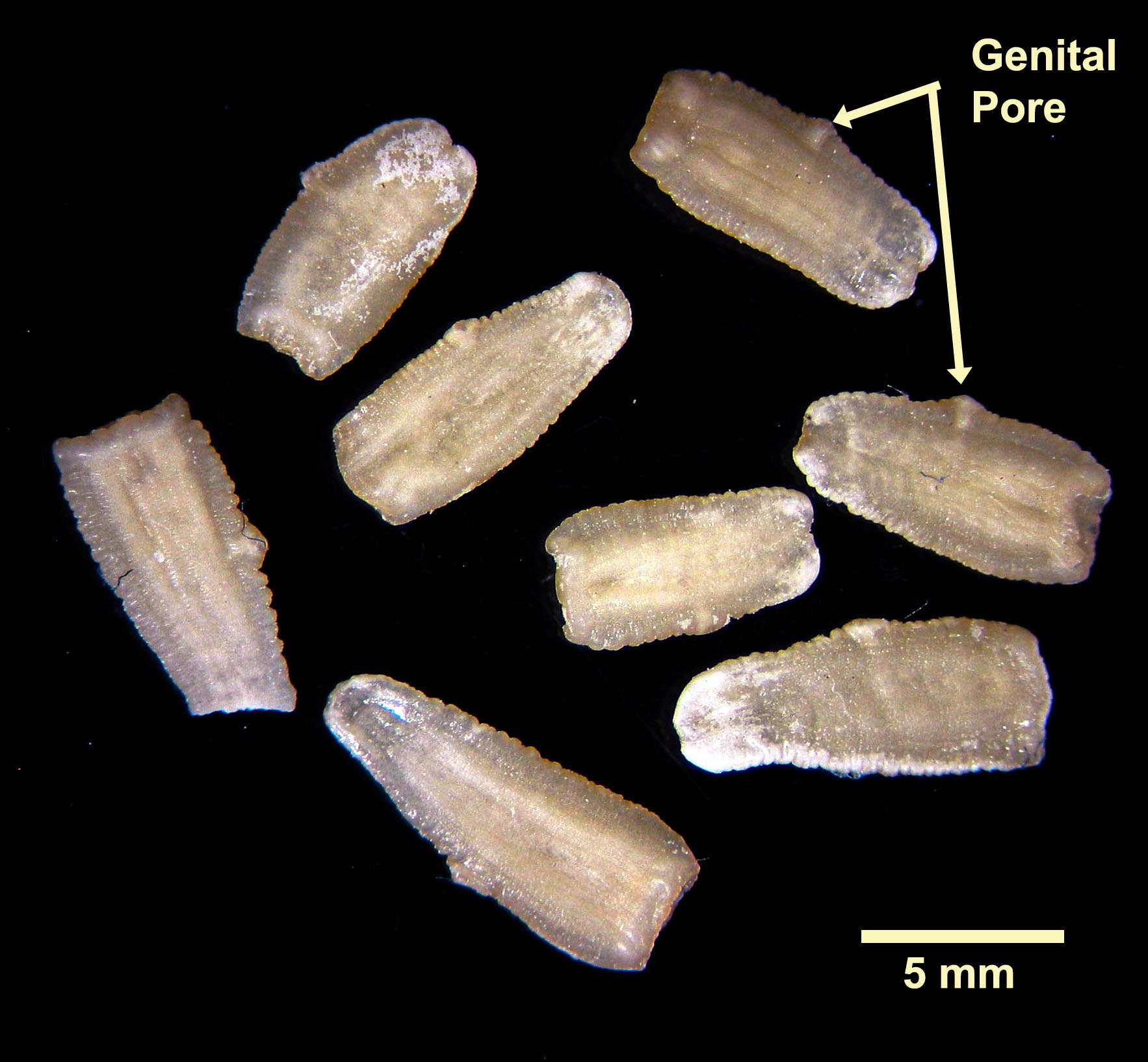

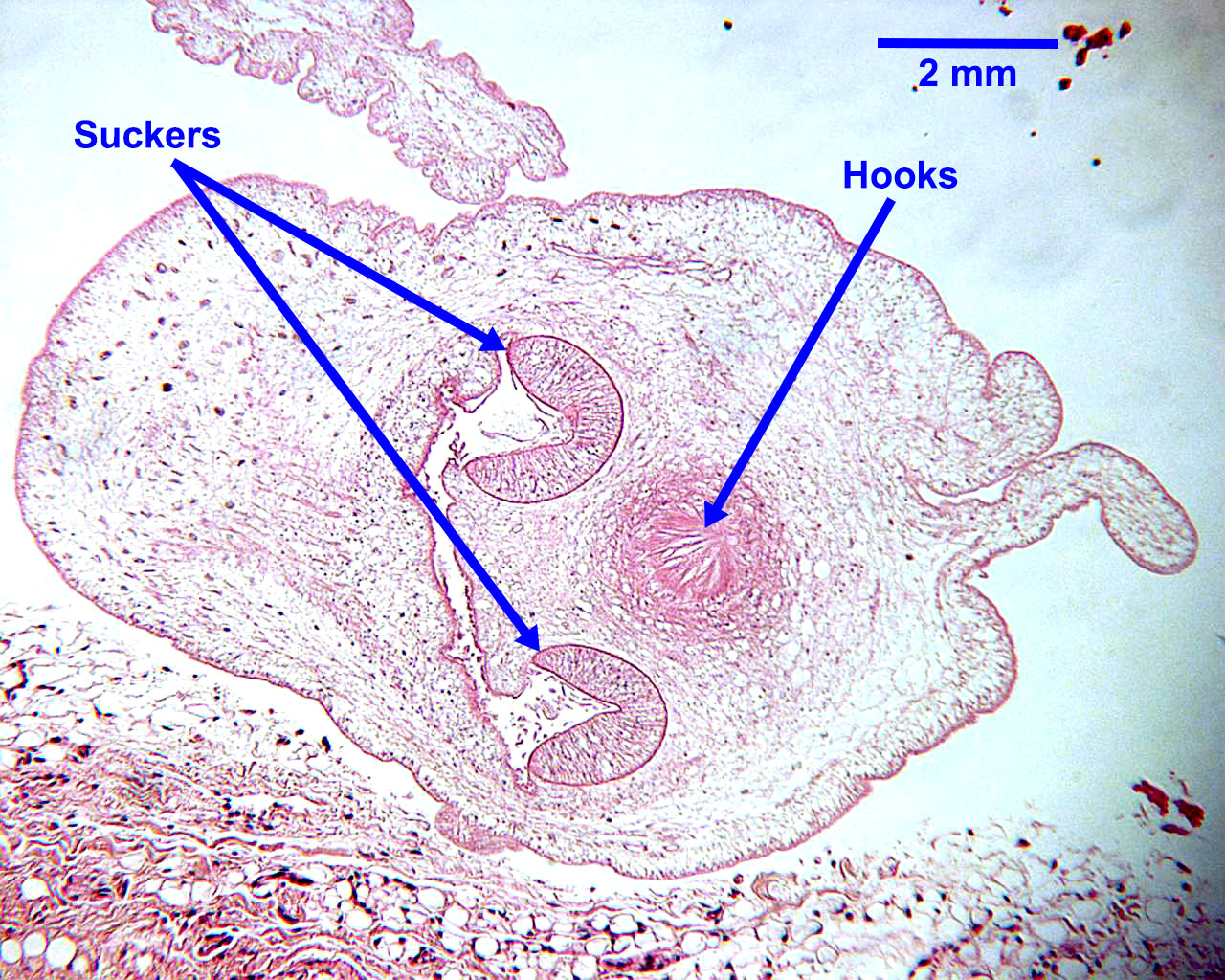

Adults of the species of Taenia that infect dogs or cats are large (up to 100 cm in length, or more) and have an anterior scolex (attachment or holdfast organ), behind which is the ribbon-shaped body composed of segments. Typically, anterior immature segments are smaller than the mature or gravid segments towards the posterior. At the anterior tip of the scolex is a rostellum, which is armed with two circles of hooks. Behind the rostellum are four circular, muscular suckers. Each mature segment of Taenia species contains a single set of reproductive organs, with a lateral genital pore at about the mid-point of the segment. In mature segments, details of the reproductive structures can be seen in fixed and stained, but not fresh, specimens. In gravid segments, however, the laterally-branched uterus (with the structure of a “Christmas tree”) is usually visible, even in fresh specimens.

Mature segments (stained) Gravid segment (stained)

Gravid segments (unstained) Taenia spp. gravid segments found in the environment

Eggs of Taenia species are round to oval, measure approximately 30 to 35 µm in diameter and have a thick, radially striated shell. Each egg contains a hexacanth larva with six hooks, not all of which are visible in every egg. The eggs of the various species of Taenia cannot be distinguished microscopically from each other, or from the eggs of Echinococcus species.

Host range and geographic distribution

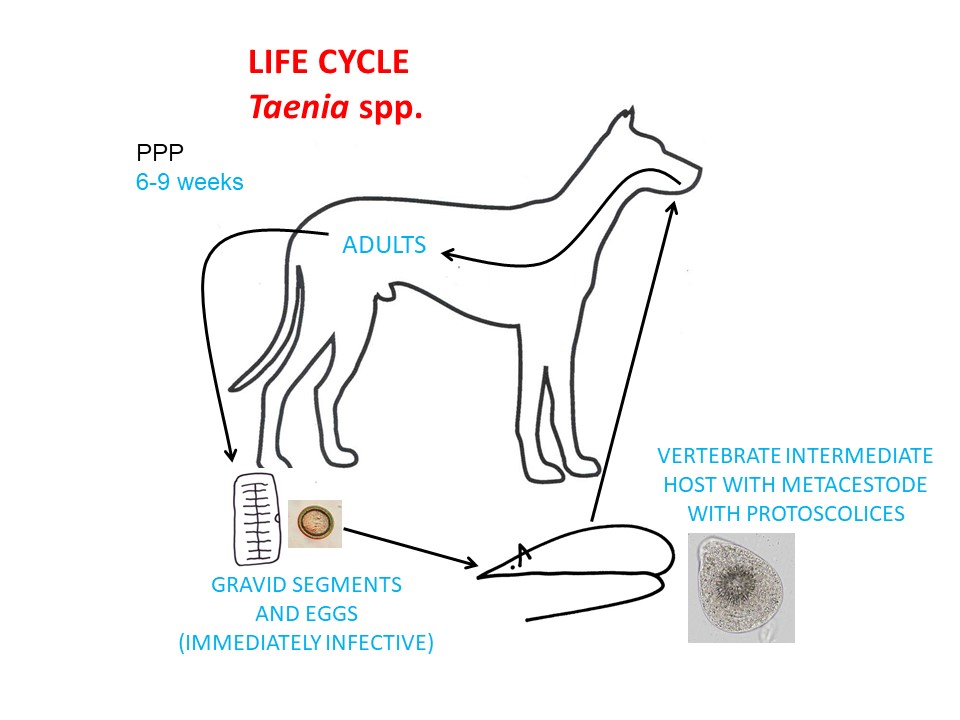

Life cycle - indirect

Adult Taenia species live in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and, like all cestodes of veterinary importance, are hermaphrodites. Gravid segments, which are full of eggs, drop off and pass intact in the feces or disintegrate in the GI lumen, releasing the eggs, which are also passed in the feces.

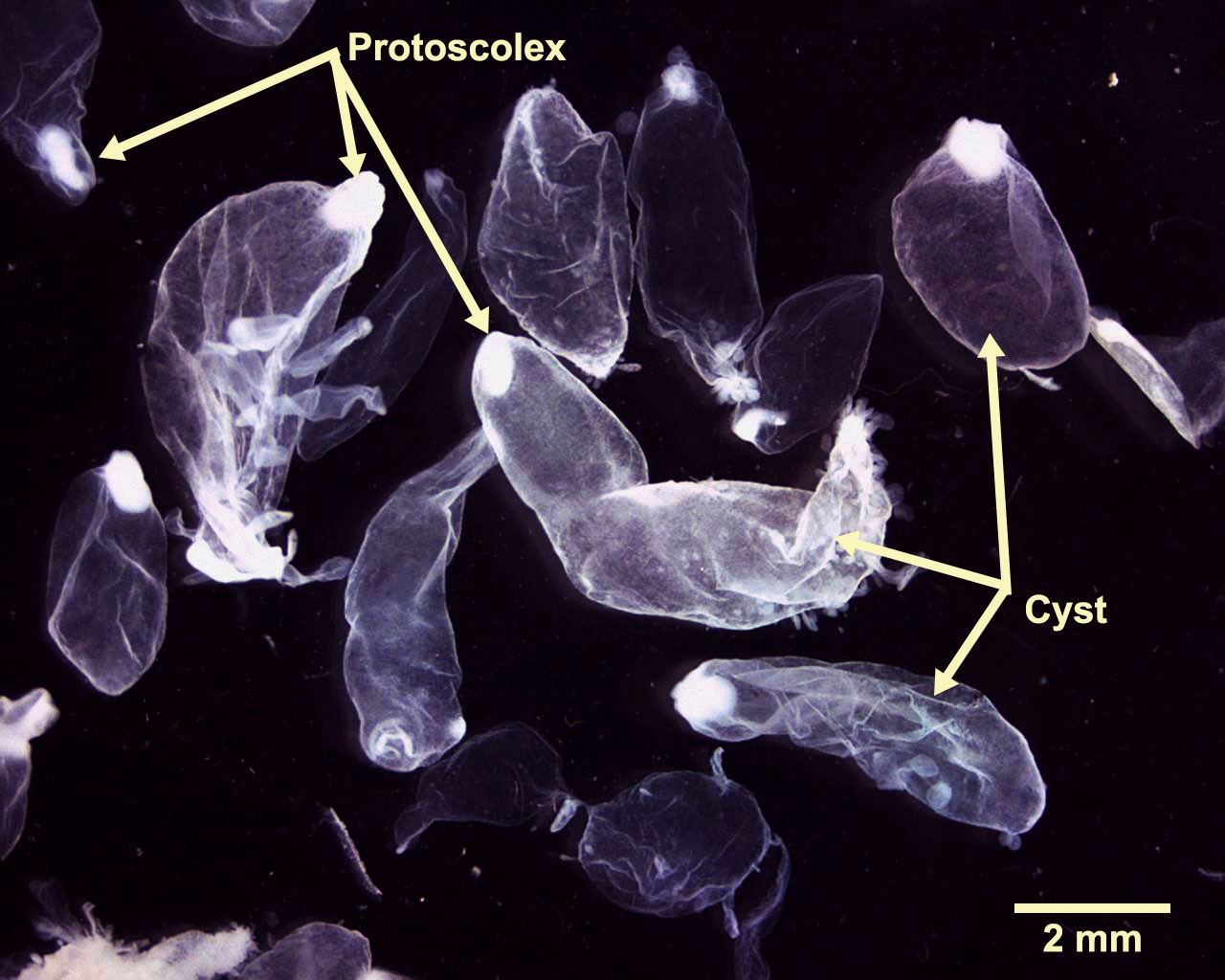

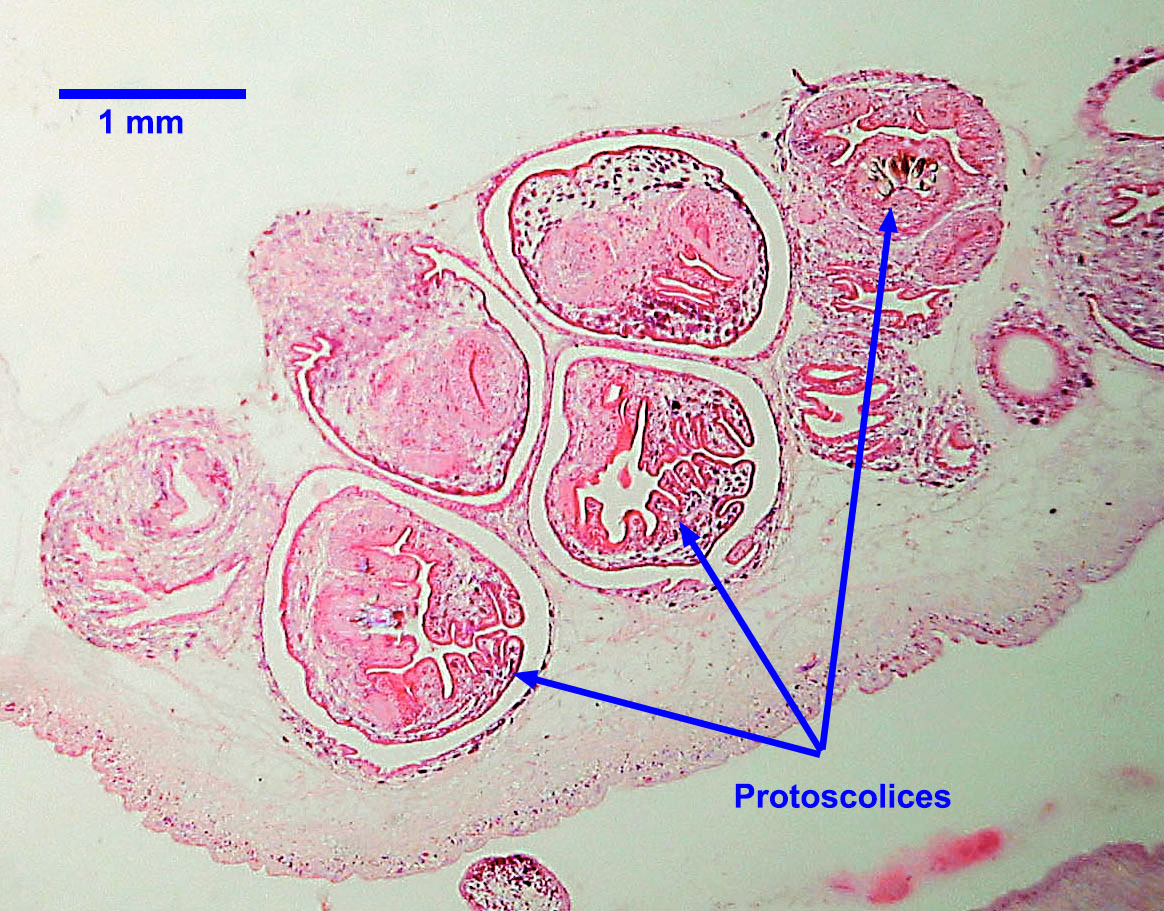

If an egg is ingested by a suitable mammalian intermediate host (required for completion of the life cycle) the egg hatches in the stomach. The hexacanth larva that is released then invades the intestinal wall – using its six hooks - and migrates in the bloodstream to various tissues, where it develops into the metacestode, or larval stage. Each species of Taenia has a specific metacestode stage; for most species in Canada, this is the cysticercus, which serves as the infective stage for the canid definitive host (T. pisiformis, abdominal organs of rabbits and rodents; T. hydatigena, abdominal organs of domestic and wild ruminants; T. ovis, muscle in sheep and goats; T. krabbei, muscle of cervids; T. polyacantha, abdominal organs of rabbits and rodents; T. crassiceps, connective tissue and body cavity of rodents). Each cysticercus contains only a single protoscolex. Each protoscolex has the potential to become the scolex of an adult tapeworm.

Cysticerci from IH Cyticercus section

The life cycle continues when the metacestode in the infected intermediate host is eaten by a dog or a cat or another suitable definitive host. Here the infective larval stage is released from the intermediate host tissues, protoscolices evert and attach to the mucosa of the small intestine, forming the scolex of the adult cestode, which buds off segments (proglottids) to form the strobila of the adult cestode. The pre-patent period varies for different species but is roughly 6-9 weeks.

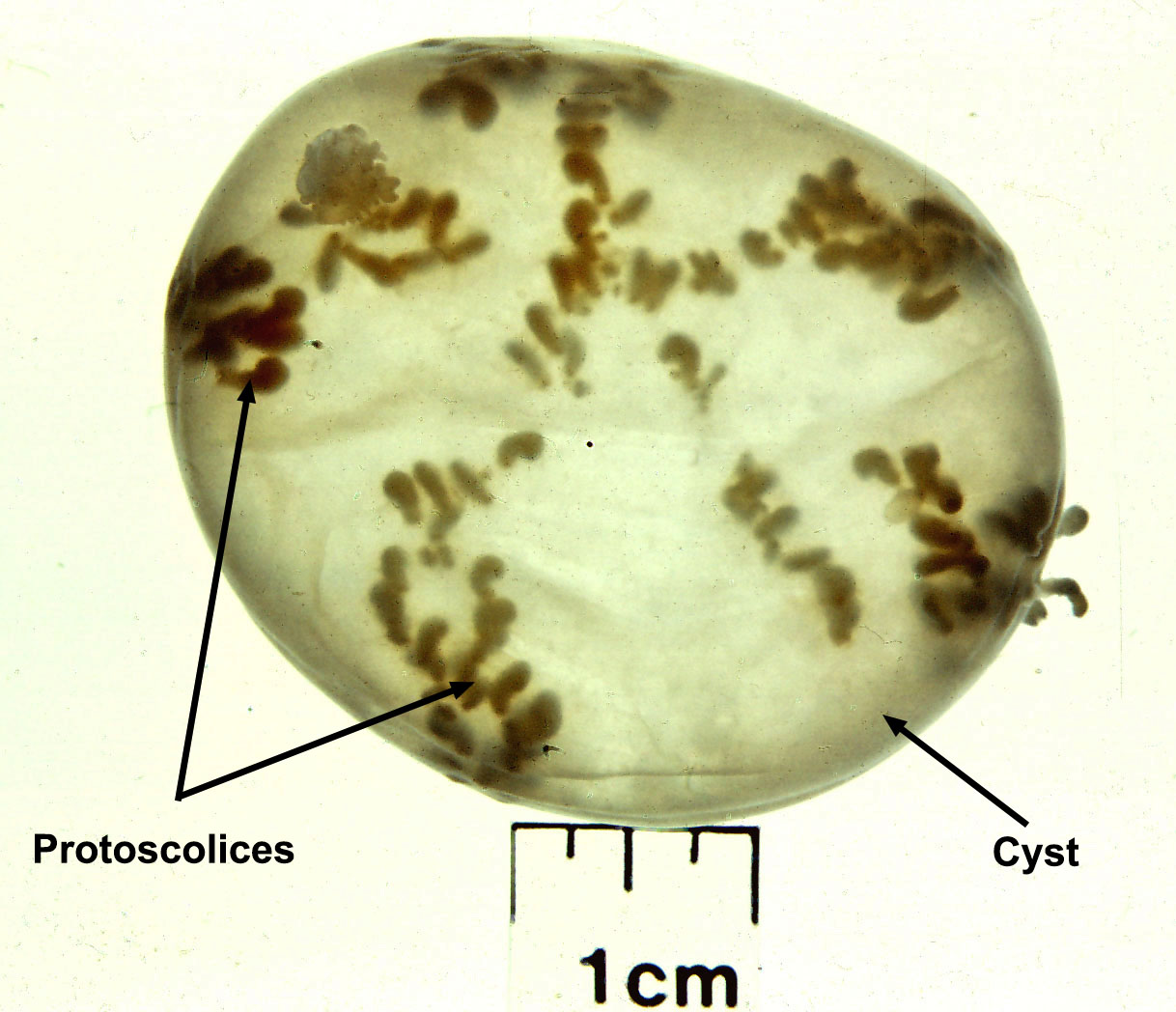

Taenia taeniaeformis has an atypical metacestode stage called a strobilocercus, which is found in the liver of rodents. For T. multiceps (not in Canada) and T. serialis, the larval stage is a coenurus, which develops from a single egg and which contains several protoscolices attached to the wall of the thin walled cyst. In these two species, therefore, the parasite can increase its numbers in the intermediate hosts (T. serialis, connective tissue of rabbits; T. multiceps, central nervous system and connective tissue of wild and domestic ungulates). While dogs and cats are generally definitive hosts for Taenia spp., rarely dogs, cats, and people can serve as aberrant intermediate hosts for Taenia spp., sometimes with serious consequences (i.e. coenurus of T. serialis in the brain of cats).

Coenurus from IH Coenurus section

Epidemiology

Pathology and clinical signs

Diagnosis

The gravid segments and eggs of the Taenia that infect dogs and cats cannot be identified to the species level macroscopically; this requires microscopic examination of the hooks on the rostellum or, most recently, commercially available coproPCR methods which can detect non-patent infections and differentiate Taenia from Echinococcus spp., important because of the zoonotic potential of the latter.

Treatment and control

Public health significance

References

Kolapo T et al. (2021) Copro-polymerase chain reaction has higher sensitivity compared to centrifugal fecal flotation in the diagnosis of taeniid cestodes, especially Echinococcus spp, in canids. Veterinary Parasitology 292 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109400

Villeneuve, L. Polley, E.J. Jenkins, J.M. Schurer, J. Gilleard, S. Kutz, G. Conboy, D. Benoit, W. Seewald, F. Gagné. 2015. Parasite prevalence in fecal samples from dogs and cats across the Canadian provinces. Parasites and Vectors 8:281 doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0870-x

https://research-groups.usask.ca/cpep/parasites/cestodes-supplementary.php