I feel a little late to this whole blogging thing so please bear with me whilst I get into the swing of writing. My name is Lauren Baker and I am a 21 year old PhD student in Plant Science at the University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington campus. I spent my undergraduate years at the same campus studying first Applied Biology before swapping to Plant Science in my third year (but that’s another blog all together!).

I hope to write a blog showing you not just what I am studying, but exactly what a PhD entails; believe it or not we don’t get the massive holidays undergraduates do and yes, it is a real job! (Rant over).

It’s nearly Christmas and I’ve been working on my PhD officially since the 1st October 2014, although I was a bit keen and started looking around the week before and found my desk!. It is now suitably messy!

I have joined a team of scientists working on wheat crop improvement using genetics, but not GMOs. I personally have no qualms with GMOs, they have vast potential to help feed an ever growing population, however our work is different. We are simply looking at genetic variation already existing in the wheat population and in its wild relatives such as rye and tall wheatgrass.

Current global issues facing crop production include drought, diseases, pests, salinity increases, soil structure destruction and nutrient deficiency. Imagine you have a field where you grow wheat and in one year you lose over 50% of your crop due to severe drought. Obviously a wheat crop with natural, improved drought tolerance would be an attractive concept for you to plant the following year!

Using genetic concepts we can identify relatives of wheat with this natural tolerance and then crossbreed this relative with common bread wheat in an attempt to produce drought resistance offspring.

I have spent a lot of my three months on the job so far researching previous work done on wheat and there really are some fantastic papers out there:

Shewry P.R. (2009) Wheat: Darwin Review. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 1537-1553.

This paper is a great review to get the ball rolling in terms of understanding what makes wheat such an attractive crop today and how it evolved. Whilst researching all this work I have produced my first literature review on the topic, identifying exactly which wild relative I am going to be working on and what I hope to achieve. If anybody wishes to read it in full (its really not amazing) please just ask and Ill happily send it out.

I have also spent a great deal of time learning my basic skills needed for the next four years. Emasculation is the first of these three skills – it involves removing all of the stamen (male parts) of the wheat ears before they start producing pollen. This prevents the wheat plant from self-pollinating itself and requires some supreme tweezer skills. Below is a picture I took of a wheat ear after I had removed the green stamen – the white fluffy bit on show is the stigma (female part).

It’s a fiddly job! For every stigma shown there are three stamen that circle it and ideally you want to avoid damaging the stigma whilst getting the stamen from around it!

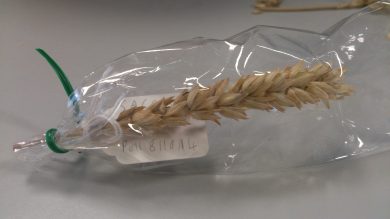

Once emasculated we contain the wheat ear in a plastic bag to prevent any cross-pollination from neighbouring wheat plants we don’t manage to emasculate on time.

After a few days of maturing, this wheat head is now ready for pollination. Going back to our drought resistance analagy, at this stage you would select a drought resistant wheat relative plant that is giving off pollen. You then remove stamen from this plant and gently “shake” or “rub” the stamen onto the stigma of the wheat plant, hopefully causing pollination! (There’s a few more steps involved in this bit but Ill go into that another time otherwise you’ll be reading all day!)

The third and final job is threshing. This happens after you harvest the wheat ears and place them in another bag as shown below.

Threshing is a very simple job done in the lab where a radio is essential in keeping you going. You carefully open each piece of the ear to see if seed has grown and separate the seeds into their own little pile. The only thing you have to avoid is the clouds of dead bugs that sometimes accompany the ear into the lab!

Threshing is a very simple job done in the lab where a radio is essential in keeping you going. You carefully open each piece of the ear to see if seed has grown and separate the seeds into their own little pile. The only thing you have to avoid is the clouds of dead bugs that sometimes accompany the ear into the lab!

The picture below shows you a wheat ear with a seed still inside (its the darker brown bit).

Hopefully when you’re done you’ll have a nice little pile of seeds which you store in their own bag with what they are on it, how many seeds you’ve collected and the date you collected them on! Job done!

Hopefully when you’re done you’ll have a nice little pile of seeds which you store in their own bag with what they are on it, how many seeds you’ve collected and the date you collected them on! Job done!

Sorry this first post has been so long but I thought I’d get the basics out the way first and not bore you with them later.

Thank you to anyone who reads and I wish you a very Merry Christmas!