“Recite the story of the battle at Dan-no-ura,—for the pity of it is the most deep.”

Then Hōïchi lifted up his voice, and chanted the chant of the fight on the bitter sea,—wonderfully making his biwa to sound like the straining of oars and the rushing of ships, the whirr and the hissing of arrows, the shouting and trampling of men, the crashing of steel upon helmets, the plunging of slain in the flood. And to left and right of him, in the pauses of his playing, he could hear voices murmuring praise: “How marvelous an artist!”—“Never in our own province was playing heard like this!”—“Not in all the empire is there another singer like Hōïchi!” Then fresh courage came to him, and he played and sang yet better than before; and a hush of wonder deepened about him. But when at last he came to tell the fate of the fair and helpless,—the piteous perishing of the women and children,—and the death-leap of Nii-no-Ama, with the imperial infant in her arms,—then all the listeners uttered together one long, long shuddering cry of anguish; and thereafter they wept and wailed so loudly and so wildly that the blind man was frightened by the violence and grief that he had made.

The Story of Mimi-nashi Hōichi,

from Kwaidan by Lafcadio Hearn

Hi blog.

Happy New Year and all that.

I’m resting up on the last couple of days of my winter holidays before the rush that is third term, not to mention dealing with my eldest trying to get into university.

We just had a reasonably heavy snowfall (9cm in central Tokyo), but luckily almost all of it has already melted away. Ice on roads and footpaths is NOT a good thing. I still have mental scars from my exchange student days in Hokkaido and the perils of walking a couple of hundred metres to the bus stop and slipping over every few paces.

This blog post was inspired by the post “Akama Shrine and the Tale of Hoichi the Earless” from fellow Japan-based blog Going Batty with Matty. Do yourself a favour and check out what Matty has to say.

It was interesting that almost as soon as I read the title I thought to myself, “I wonder if he’s going to mention the crabs.”

In summary:

In the final decisive battle between the Minamoto (AKA Genji) and Taira (AKA Heike) clans in their feud – which escalated into a civil war – the Minamoto emerged victorious in their naval engagement, despite the Taira traditionally having the stronger maritime force. Several Taira lords were killed in the battle, and the child emperor Antoku was drowned when his nurse/grandmother jumped into the sea with him in her arms to avoid capture. Folklore has it that many of the Taira samurai also threw themselves into the sea.

There is a kind of crab, commonly known as the heikegani (平家蟹, literally “Heike crab”), with patterns on its carapace that resembles an angry human face. These crabs are said to be the souls of the lost Heike clan. It is said that fishermen throw them back out of respect for (or fear of) the Heike.

Hearn summed it up nicely:

More than seven hundred years ago, at Dan-no-ura, in the Straits of

Shimonoseki, was fought the last battle of the long contest between the

Heike, or Taira clan, and the Genji, or Minamoto clan. There the Heike

perished utterly, with their women and children, and their infant emperor

likewise — now remembered as Antoku Tenno. And that sea and shore have

been haunted for seven hundred years… Elsewhere I told you about the

strange crabs found there, called Heike crabs, which have human faces on

their backs, and are said to be the spirits of the Heike warriors.

But then a question formed in my mind. “If the name heikegani stems from the events of the Battle of Dan-no-Ura, what were these crabs called before 1185?”

This led me on a search which turned up alternative names including kiyotsunegani, takebungani and shimamuragani, all of which are named after historical or semi-historical characters who drowned themselves. Furthermore, two of these characters lived long after the events of 1185 and the other died just two years before.

Not only did crabs number among the yokai of Japanese folklore, it seems that the lost souls of heroes who died at sea reappear as crabs in a number of stories.

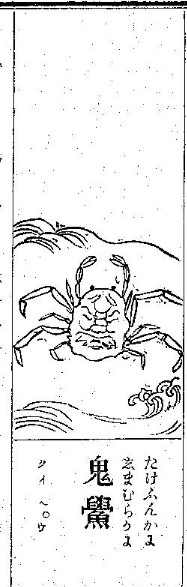

The Wakansansaizue uses the names takebungani and shimamurakani, plus the name onigani (鬼蟹), but my research suggests the earliest recorded use of this name as coming from the 16th century.

A name given to the crabs in parts of Kochi Prefecture is kumogani, literally “spider crab”. It must be noted that heikegani belong to a different family from the groups known as spider crabs in English.

I also wondered about the narrative that these crabs are not eaten. That seems to be true – all the sources I could find suggested the crabs are not sold commercially, and I wasn’t able to find any references to either the crabs being eaten, or any reason (beyond folklore) why they can’t be eaten. Maybe size has something to do with it – the crabs’ shells rarely exceed a width of 20 mm or so.

Confusing the issue further is the number of similar and closely related crabs. In addition to Heikeopsis japonica, I have found references to Heikeopsis arachnoides, Paradorippe granulata, Dorippe sinica, Ethusa quadrata, E. sexdentata, and E. izuensis, while the Japanese carcinologist Tsune Sakai suggested that there are at least 17 different species of crabs in two families in the Indo-West Pacific that are similar enough to be called Heike-gani by local residents.

Let us return to Hearn, this time from Kotto:

These reflections were induced by a box of crabs sent me from the Province of Chōshū,—crabs possessing that very same quality of grotesqueness which we are accustomed to think of as being peculiarly Japanese. On the backs of these creatures there are bossings and depressions that curiously simulate the shape of a human face,—a distorted face,—a face modelled in relief as a Japanese craftsman might have modelled it in some moment of artistic whim.

Two varieties of such crabs—nicely dried and polished—are constantly exposed for sale in the shops of Akamagaséki (better known to foreigners by the name of Shimonoséki). They are caught along the neighbouring stretch of coast called Dan-no-Ura, where the great clan of the Heiké, or Taira, were exterminated in a naval battle, seven centuries ago, by the rival clan of Genji, or Minamoto. Readers of Japanese history will remember the story of the Imperial Nun, Nii-no-Ama, who in the hour of that awful tragedy composed a poem, and then leaped into the sea, with the child-emperor Antoku in her arms.

Now the grotesque crabs of this coast are called Heiké-gani, or “Heiké-crabs,” because of a legend that the spirits of the drowned and slaughtered warriors of the Heiké-clan assumed such shapes; and it is said that the fury or the agony of the death-struggle can still be discerned in the faces upon the backs of the crabs. But to feel the romance of this legend you should be familiar with old pictures of the fight of Dan-no-Ura,—old coloured prints of the armoured combatants, with their grim battle-masks of iron and their great fierce eyes.

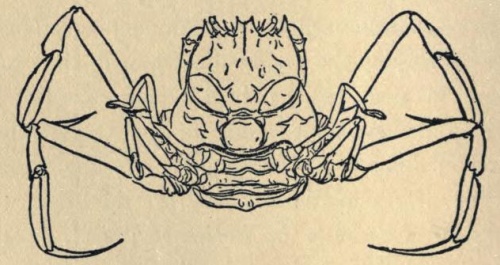

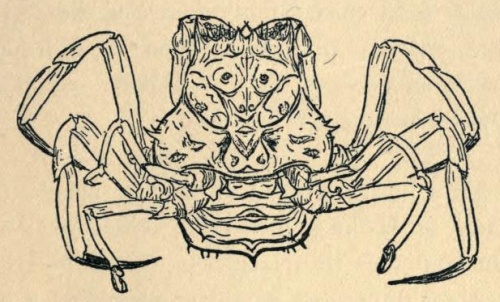

The smaller variety of crab is known simply as a “Heiké-crab,”—Heiké-gani. Each Heiké-gani is supposed to be animated by the spirit of a common Heiké warrior only,—an ordinary samurai. But the larger kind of crab is also termed Taishō-gani (“Chieftain-crab”), or Tatsugashira (“Dragon-helmet”); and all Taishō-gani or Tatsugashira are thought to be animated by ghosts of those great Heiké captains who bore upon their helmets monsters unknown to Western heraldry, and glittering horns, and dragons of gold.

I got a Japanese friend to draw for me the two pictures of Heiké-gani herewith reproduced; and I can vouch for their accuracy.

Oddly enough, I was unable to find usage of either tatsugashira or taishogani. I wonder if they are not regional names. Given the illustrations, however, we can probably be safe guessing that the upper picture is Heikeopsis japonica and the lower picture to be Dorippe sinica.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nihonbunka/26047461420/in/photostream/

Dorippe sinica, by the way, is commonly known in Japan as kimengani (鬼面蟹), literally “demon face crab”.

A commonly held misconception is that fishermen would throw back the ones that looked most like a human face, inadvertently allowing them to breed and pass on their unusual appearance to their offspring. Fossil records show the exact same patterns on crabs that existed before the appearance of humans, and these crabs are eaten in other parts of the world but show no difference in pattern from ones in Japan.

So, while I never did solve the mystery as to the original name for the crabs, I learned a great deal while doing my research.

Again, a big shout out to Going Batty with Matty.

Thank you for the shout out! Excellent post! I learned a lot about heikegani and realized my mistake about fishermen throwing them back. I will cut that part out of my post haha