After the culture loss experienced due to US nuclear experiments in the mid 20th century, the Marshall Islands face now the threat of climate change

G16epd

Huge mushroom cloud hangs over Bikini Atoll during an American atomic bomb test in a colourised image, 1946. Photograph courtesy of Science History Images/Alamy

Between 1946 and 1958, the United States tested 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands. The most powerful of these tests was Bravo, a 15-megaton device – a thousand times more powerful than the bomb exploded over Hiroshima – detonated on 1 March 1954 at Bikini Atoll. A second sun rose in the sky that morning, followed by the roar of thunder, winds at tornado strength and powerful earthquakes. Radioactive fallout from the blast was carried by the wind to the east, where it reached the inhabited atoll of Rongelap several hours later. People brushed the powder from their food and ate; they cleared it from their water cisterns and drank; children swimming in the lagoon put it in their hair and pretended it was soap. Shortly thereafter, the 64 people on Rongelap that day began to suffer the ill effects of acute radiation exposure: their hair fell out, their skin was burned, they began to vomit, and they suffered from a thirst water could not quench.

Two days later, the US Navy evacuated the people of Rongelap; they were subsequently resettled on Ejit island in Majuro Atoll, at the centre of the Marshall Islands. In 1957, three years after Bravo, the people of Rongelap returned home. They were assured that the background levels of radiation were within the parameters of safety. Yet the people of Rongelap were not informed about their increased risk from the contaminated food and water they continued to consume for many years, which resulted in their elevated rates of certain types of cancer and unusual numbers of miscarriages and birth defects. These health problems, combined with the release of additional information about their exposure to radiation, prompted the community to leave its atoll again in 1985, 31 years after the original event. Most of the people from Rongelap currently reside on Ebeye island, adjacent to the proving grounds for the US missile defence system in Kwajalein lagoon; on Mejatto island; and in the capital city, Majuro.

Gettyimages 172887476

US military commander Commodore Ben Wyatt (left) talks to islanders ahead of their evacuation to allow for the Operation Crossroads nuclear weapons test, Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, 1946. Photograph courtesy of Carl Mydans/the LIFE Picture Collection/Getty

Leaving bikini 1946g

People from Bikini Atoll being evacuated prior to the testing of US atomic weapons, 1946. Photograph courtesy of AP/Rex/Shutterstock

In 1999, I joined two other anthropologists in the Marshall Islands for preliminary research in support of a case representing the people of Rongelap Atoll before the Nuclear Claims Tribunal. The tribunal was established to adjudicate compensation for loss and damage to persons and property resulting from exposure to radiation and other negative consequences of nuclear weapons testing by the United States during the 1940s and 1950s.

‘Adequately conveying the experiences of the people from Rongelap requires paying attention to their concerns about “culture loss” – of knowledge, ideas and practices of value’

Adequately conveying the experiences of the people from Rongelap requires paying attention to their concerns about ‘culture loss’. This does not refer to disappearance of entire societies or ways of life but the loss of particular things – knowledge, ideas and practices of value. Local vocabularies are often inadequate to account for these experiences, which have therefore found expression in terms of culture. This suggests that the concept of cultural property rights can provide a means to identify these losses, which might otherwise be obscured or ignored.

Aaeaaqaaaaaaaa3paaaajgmxogfkmdc2lwmyntytngnjzi04yzazltjhytu5zjbhywnlza

US military and VIPs observe atomic detonation from Enewetak Atoll, 1951. Photograph courtesy of US Air Force

Gettyimages 838118674

Vice-Admiral Blandy (left), Mrs Blandy (centre) and Admiral Lowry (right) with the atom bomb cake served at the Army War College in Washington DC in 1946, in recognition of the nuclear testing programme on Bikini Atoll. Photograph courtesy of Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho/Getty

During an advisory committee meeting with representatives from Rongelap, we were told, ‘you cannot put enough value on land … How do you put a value on something that people consider as a living thing that is part of your soul?’ Several committee members framed their concerns with reference to loss, especially the loss of culture, including the observation, ‘When the bomb exploded, the culture was gone, too. It is impossible for people to act in their proper roles’. Another person we interviewed explained, ‘We have lost our knowledge, our ability, our moral standing, and self-esteem in the community. What we were taught is no longer practical … A lot has been lost, not just our land’.

‘You cannot put enough value on land … How do you put a value on something that people consider as a living thing that is part of your soul?’

One example of culture loss stems from the lack of access to the resources necessary for canoe building, which has affected communication of these practices across generational lines. Women on Enewetak no longer teach their daughters how to weave the mat sails for outrigger canoes because the necessary varieties of pandanus are unavailable, and men no longer teach their sons how to build sailing canoes because they do not have access to the tall, straight breadfruit trees used in fashioning canoe hulls. The knowledge of how to construct and maintain the long-distance sailing canoes of Enewetak, unique in design, may already have been forgotten. On Rongelap, the consequences of nuclear testing and relocation have also ‘terminated the transmission of navigational knowledge’ needed for inter-island sailing, including the ability to maintain course by tracking the rising and setting of the stars, and by interpreting ‘changes in wave action occurring when sea swells strike the islands of the chain’, known as wave piloting. Such knowledge is cultural property, and its value should be recognised.

Fmib 33842 sailing canoe, rongelabtc copy edit

Long-distance sailing canoe (walap) at Rongelab Atoll, Marshall Islands, c.1900. Photograph courtesy of the Freshwater and Marine Bank

Sailing canoe brailed on starboard tack, jaliut lagoon, marshall islands (1899 1900)

Marshall Islands outrigger sailing canoe in Jaliut lagoon, 1900. Gulf of Maine Cod Project, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Sanctuaries. Photograph by Stefan Claesson/National Archives

During interviews on Majuro, informants described how they had become dependent on the cash economy since their relocation from Rongelap. Contemporary replacements for traditional subsistence practices require capital investment. For example, whereas fishing grounds in Rongelap were accessible to all without restriction, in Majuro and Ebeye only people with boats and fuel are able to fish. A man from Rongelap explained the transformation in terms of restrictions on his personal autonomy: ‘If you live in town, you are like a guest in someone’s house, [whereas] on your own land, you feel freedom’.

‘Any discussion of change must acknowledge its potential benefits. Yet it is difficult to conceptualise the losses experienced by the people affected by nuclear testing as productive’

Any discussion of change must acknowledge its potential benefits. Yet it is difficult to conceptualise the losses experienced by the people affected by nuclear testing as productive. Their land was not transformed into something of value; rather, it was destroyed because it was of value to the US government only in its potential loss. This is negative reciprocity writ large across the landscape: the wholesale destruction of things (property, land, memory) and social relations organised through land, including the capacity for reproducing these relationships in place.

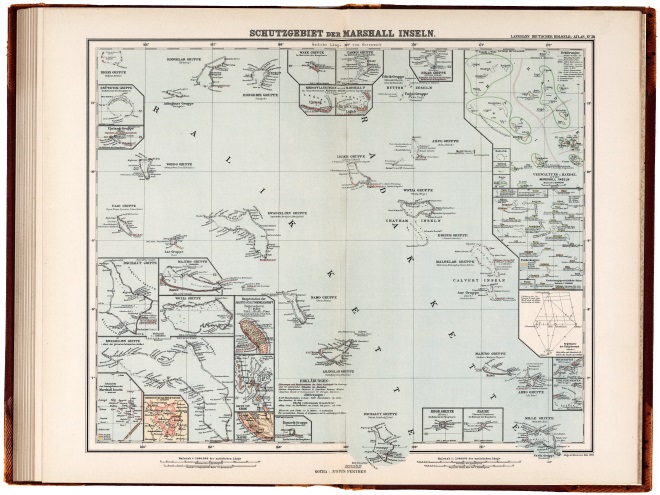

Schutzgebiet der marshall inseln deutscher kolonialatlas 1897 justus perthes karte 30 tc

Paul Langhans’ map showing the Marshall Islands as a German protectorate in 1897. Image courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection

14783361945 0b6ff21be2 o

Marshall Islands stick chart representing ocean swell patterns, and how these are disrupted by the islands. These diagrams are memorised during navigational training

On 17 April 2007, the Nuclear Claims Tribunal issued its decision in the Rongelap case, ‘calling for payment of just over $1 billion in compensation to the claimants, a figure reflecting the costs for remediation and restoration of Rongelap (and associated islands/atolls), future lost property value and compensation for damages from nuclear testing’. The award was substantially greater than prior judgments by the Nuclear Claims Tribunal for Enewetak ($323 million in 2000), Bikini ($563 million in 2001), and the smaller atoll of Utrik ($307 million in 2005). Each successive award incorporated and expanded on previous determinations in calculating the appropriate level of compensation. The tribunal had already established that compensation rates should be set with reference to the ‘highest and best use’ of land, which they identified as residential and agricultural use rather than government purchase or rental. Consequently, the award to the people from Rongelap was based on lost use-values rather than real-estate transactions.

‘The environmental threats experienced by the people living in the Marshall Islands are examples of slow violence, the consequences of which have historically been neglected in comparison with sudden, catastrophic events such as an oil spill or a tsunami, which remain the archetype for disaster and intervention’

According to the tribunal, all specific cultural values were taken into account by the accounting procedures for residential and agricultural use, including loss of access to ‘lagoon, reef heads, clam beds, reef fisheries, [and] turtle and bird nesting grounds’, ‘damage and loss of access to family cemeteries, burial sites of iroij [chiefs], sacred sites and sanctuaries, and morjinkot land’, which was given by chiefs to commoners for bravery in battle. The tribunal even argued that land that was culturally significant, but which had no economic value – providing the example of an uninhabited and unused outer island in an atoll – was implicitly included in their analysis.

Screen shot 2018 02 26 at 13.09.56 copy edit

Nuclear fallout on Rongelap Atoll after the 1954 Bravo test, Marshall Islands. Image courtesy of Bill Nelson/Stuart Kirsch

Gettyimages 475693381

People from Rongelap Atoll exposed to radiation and their descendants march in the capital city of Majuro on the 60th anniversary of the nuclear explosion that led to their exile, 2014. Photograph courtesy of Isaac Marty/AFP/Getty

The claims made by the people of Rongelap about the problems resulting from their ‘inability to interact in a healthy land and seascape in ways that allow the transmission of knowledge’ were not explicitly recognised as a separate category of compensation by the Nuclear Claims Tribunal. The tribunal did not challenge or dispute arguments about the ‘loss of a way of life’ or ‘culture loss’, but concluded they were adequately addressed by the award for the loss of use.

In the Marshall Islands case, there is a fundamental incommensurability between what was taken and what might be given back in the form of compensation. When an equivalent is unavailable, the substitute is always inferior to the original, perpetuating the original sense of loss. The issue arises in both the payment of monetary compensation and attempts to imagine the possibilities of compensation in kind. Legal forums that adjudicate claims of loss might also be seen to further commodification by establishing monetary values for cultural property that previously existed outside economic domains.

‘In the Marshall Islands case, there is a fundamental incommensurability between what was taken and what might be given back in the form of compensation’

Although money is hardly an ideal substitute, it can be used as a means to other ends – to decontaminate Rongelap Atoll, for example – that cannot otherwise be achieved. Legal activism can provide important political and economic resources for indigenous peoples, particularly when the terms of the debate are otherwise set and the mechanisms of justice controlled by non-indigenous bodies. Nonetheless, not all losses are compensable or even judicable. The acknowledgement of loss, however – along with appropriate acts of commemoration, historical documentation, and, where relevant, acceptance of responsibility, in addition to the implementation of reforms designed to prevent past wrongs from recurring – is a partial but valuable response to the experience of culture loss.

Majuro atoll 2009

Seven of the 1,225 islands in the Marshalls. The average elevation in the Marshall Islands is only 1 metre above sea level, and the highest point in the island chain is only 10 metres above sea level. Photograph by Peter Rudiak-Gould

Questions about culture loss have acquired new salience in the context of global climate change. Not only are the people living in the Marshall Islands still grappling with the radioactive legacy of nuclear weapons testing, but they also face potential inundation from rising sea levels. Like the claims about loss and damage from nuclear weapons testing adjudicated by the Nuclear Claims Tribunal, the adverse effects of global climate change raise questions about the assessment of values that are not adequately measured by the market. In both cases, the environmental threats experienced by the people living in the Marshall Islands are examples of slow violence, the consequences of which have historically been neglected in comparison with sudden, catastrophic events such as an oil spill or a tsunami, which remain the archetype for disaster and intervention. The novel application of previous work on the consequences of nuclear weapons testing to the potential impacts of climate change shows how the analysis of local contexts can have global significance. Whereas exposure to radiation forced the residents of several atolls to relocate, rising sea levels may imperil the social and cultural reproduction of the entire population of the Marshall Islands.

Extract from: Stuart Kirsch, Chapter 5: ‘How Analysis of Local Contexts Can Have Global Significance: Double Exposure in the Marshall Islands’, Engaged Anthropology: Politics Beyond the Text, University of California Press, 2018.

This piece is featured in the AR’s April 2018 issue on Rethinking the rural – click here to purchase a copy

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design