Allied troops who had the misfortune to be taken prisoner by the Japanese during World War II quickly learned that the Geneva Convention might as well not exist. Indeed, they endured years of not only malnutrition and starvation, disease and general neglect -- resisting all the while -- but also torture, slave labor and other war crimes.

Many POWs were murdered outright by their captors. In fact, only a little more than half of them ever saw home again. Here are some of their experiences, their stories of strength and resilience, based on interviews with and oral histories from veterans and the daughter of a POW.

PUNISHMENT

"Four of our group escaped. I -- along with three other men -- was taken to the Japanese commander. He alternated [between] questioning and beating us with a belt and a bamboo stick from 8 in the morning until 3 in the afternoon. The four of us denied knowing anything about the escape. Actually, we knew everything. We were finally taken back to our compound and the guards took our four top officers to the commander. We saw a Jap firing squad take them out of sight and heard the shots as they were executed."

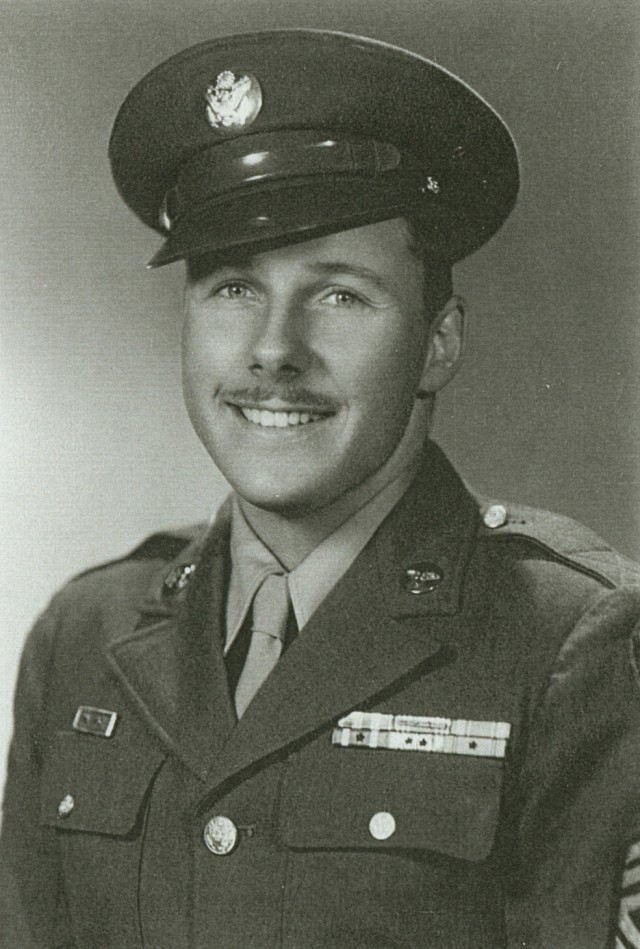

-- Tech. Sgt. Richard Henry Peterson, Army Air Corps, via the Veterans History Project.

"There were 10-man squads and, if one of you escaped, the other nine would be killed. There were two or three of those situations that happened and nine men got their heads chopped off."

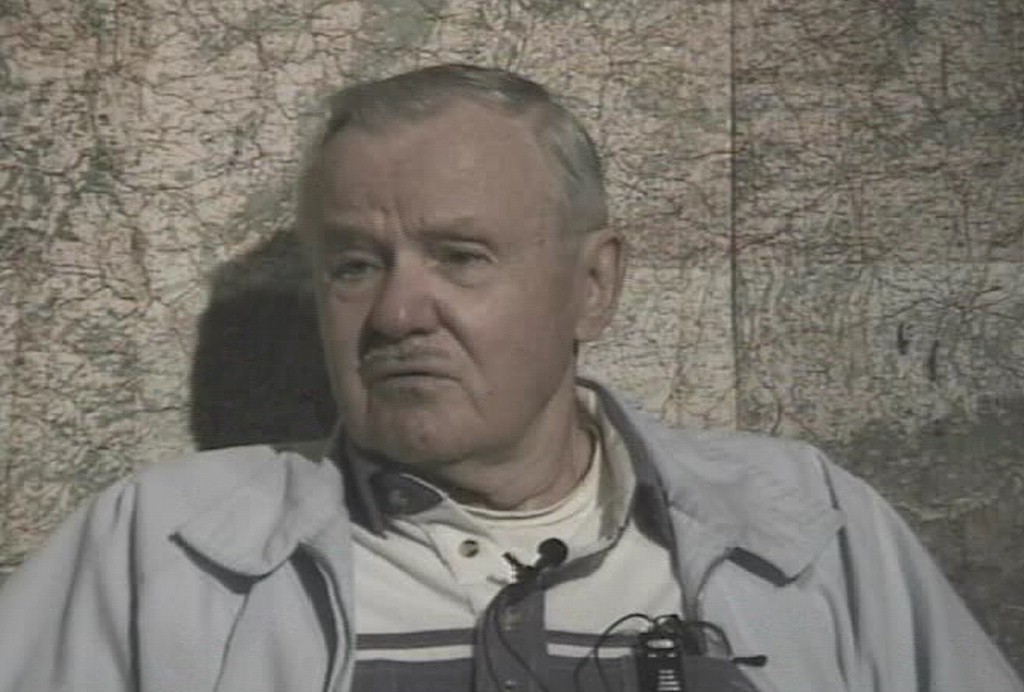

-- Staff Sgt. Henry Wilayto, former commander of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, via the Veterans History Project.

FOOD AND ILLNESS

"We got a green concoction that was made from the tops of potato plants. I don't think it had much nourishment in it. It kind of colored the water green. You could chew it for months and you couldn't break it down. The rice was filled with silt and worms. You'd get about two thirds of a mess kit, a couple of times a day. I think the consensus of experts is that we were fed about 700 calories a day and we were expending thousands."

-- Pvt. Dan Crowley, Army Air Corps.

"Rations for sick men were cut by one third, but we divided all food equally. The Japs weighed us every week. They were keeping records on how much food was needed to keep us alive and working. In August 1943, I went down to 114 pounds and had a pain in my side. It turned out to be a bad case of pleurisy. With a temperature of 103 degrees, I was allowed to stay in camp on light duty."

-- Peterson.

"We arrived in Japan in late November 1942. We were each issued a Japanese summer coat and pants. We wore those, day and night, for over three years. They were loaded with vermin and not sufficient to ward off the cold at the docks at Yokohama where we were put to work. The first year, we lost 30 to 50 men out of some 300. We were all skin and bones, weighing around 100 pounds. I had beriberi and pellagra. My ankles were swollen to twice normal size. I could not pass a stool without breaking open my anus. My bladder could not hold urine but a short time."

-- Chief Warrant Officer 3 John L. Stensby Sr., 60th Coast Artillery, via the Veterans History Project.

FORCED LABOR

"I was sent to the island of Palawan in the Philippines. It was the most brutal manual labor possible. We were attempting to build a runway. We had to cut down all the vegetation, even large trees. The only tools we had were manual: picks and shovels and axes and saws. The next step was to level the ground manually. Then you would dig up the rock, which was quite jagged. The distance to where you had to bring it back became longer and longer. It took about six men to push a fully loaded mine car. If you didn't get it moving and do it quickly, you were clubbed. You either worked very hard or you were beaten -- unto death if necessary. We were just north of the equator and the only clothing you had was a loincloth. We were burned black and our hair was down to our waists."

-- Crowley.

"In Taiwan, each man was given a pole across his shoulders with a bucket on each end. These were then loaded with rock. We were forced to haul rock up the mountainside from a riverbed to complete a rail bed. We went out to work when it was still dark, worked all day and came back at dark."

-- Stensby.

ENTERTAINMENT

"I started to write one-horse operas, like the poor girl whom the hero was going to marry but they didn't have any money and the mortgage was due. I transposed the characters. The girl went out to work, but the girl was the guy and the guy got pregnant. So it was as much of a farce as you could possibly build it into. Whatever we did, we included a blackout. You did a punch line and then you hit the curtain and that was the end of the show. In every camp where we had any talent at all, we would try to put on shows and invite the Japanese to come and see them. We did things that the Japanese enjoyed as much as the Americans."

-- Wilayto.

SABOTAGE/RESISTANCE

"I'm probably the only GI in the United States Army that sunk a warship single-handedly. We worked in the shipyards, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Shipyards. I was working on a big ship. The bow that hits the water first, you weld those two plates up. I cranked the transformer way on down so it wasn't hot enough to really weld. The next day we had a day off. The following morning, there was that ship, sunk in the waves. We must have thrown a thousand welding rods in the bay. We'd go back for more like we were using them up. Good workers, you know."

-- Stensby.

"We were mixing the cement by hand and filling in wooden squares. We poured probably around 10 inches. You had to smooth that and finally you had a runway, after about 3,000 feet. The first aircraft to take off on it was our Jap commander. We were supposed to love him. We had a big send off and we lined the runway. We had sabotaged the mix of concrete pretty well. The tail on his plain ripped a beautiful hole in the cement."

-- Crowley.

"We became stevedores in the Port Area POW camp in Manila Harbor. We were treated well because the Swiss Red Cross monitored that camp, so we were a show camp. I gained back 50 pounds. We had a softball field and a boxing ring. They allowed us to use the Japanese commissary. If we worked one day we would get the next day off. We had a good life there, but we were trying to destroy whatever we could.

"We unloaded alcohol drums, 55-gallon drums, and we unscrewed the caps and put them upside down so the fluid came out. When the ship went out in the harbor, sparks, bang, and it blew up. Our two officers were working with the Spanish underground. They were able to have somebody put dynamite or something under the ship and they blew it up. I saw it go up myself, right up in the air. We were on board a cargo vessel going to Japan in about 10 days. They didn't want us hanging around anymore."

-- Wilayto.

HELL SHIPS

"More than 14,000 POWs died on hell ships to Japan, Korea and China. Many of those deaths were from friendly fire from U.S. Navy bombers and submarines because these ships were unmarked. Whole transports were lost. My father was on three. The Japanese shoved 1,600 men in a space meant for 500. They couldn't move. This was in the Philippines. It's hot. They started moaning and screaming for water, screaming for air. The Japanese decided they didn't like the noises, so they put the tops on and then men started to suffocate. They started to do strange things like cut each other to drink their blood."

-- Jan Thompson, daughter of a POW, president of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society and documentary filmmaker.

"We were put aboard a ship, the Totori Maru. About 2,000 Americans were crammed into the lower deck. There was not enough room for all to lie down at once so some sat, some lay flat and some stood up. We traded places doing this for 40 days. A few men at a time were allowed to go topside once a day for 10 minutes to go to the toilet and get one canteen of water, which didn't go far. Our food for the first two weeks consisted of a cup of fish soup and crackers contaminated with soap. This gave all of us diarrhea. Soon we were all sitting in excrement. Several dozen men died and were buried at sea."

-- Peterson.

MINING

"I spent the final year and a half at a 400-year-old copper mine in Ashio, Japan. All the timbers were rotting and the overhead was very low. It was a constant stream of pebbles and small stones and water running. It was rather a frightening place. They would pack about 25 of us in an iron bucket with a cable attached to the top and drop us down this shoot about 2,000 feet every morning. They had fun every morning bouncing us up and down. We were positive that that cable that was attached to the top would snap any minute, any day."

-- Crowley.

"We worked in a nickel ore mine. The nickel ore was for rifle barrels so we were helping the Japanese war effort, which was against all international regulations. We worked 13 months. I couldn't have lasted another year. My toes were weeping. They were rotting away because we wore size-14 rubber hip boots and we were working with hot ore and there was no ventilation. I was down to 135 pounds. We had to be weighed every month. I was carrying men who couldn't walk to the scale, and then we would see little 12-inch boxes and we knew they had died and were cremated. We had one Japanese civilian who let us sit down and take a break, and would give us cigarettes. He got caught and they put him to work as a laborer."

-- Wilayto.

"I was working in the Japanese coal mines in the last days of the war. I told my buddy, 'Watch me tonight. I'm going to let one of those cars run in my leg because I'm not going to live anyways. I'm at the end of my damn rope.' I'd let it smash my leg and then they'd keep me up topside. Do you know that night the war ended? One more day and I'd have been dead or wounded for life."

-- Stensby.

SURVIVAL

"How did I survive? I haven't the slightest idea. It was a nightmare."

-- Crowley.

"One of the men said, and I have to believe this is true, 'you either survived on love or you survived on hate.' And I think for the most part, everyone hated and they hated the enemy, and there was no way they were going to let those sons of bitches walk out before they walked out."

-- Thompson.

"I realized that if you help somebody else, somehow God will help you. And that's what I did. Whenever I could, I helped somebody. And in turn, I survived. You have to have faith to survive. We did the best we could. We tried to be Soldiers the whole time we were prisoners and we tried to work against the enemy and do everything we could for our country."

-- Wilayto.

FREEDOM

"When the war ended, we marched out of our camp and went into town to get onto two trains to go to Yokohama and rejoin the Americans. They said, there is no reason to send troops out there. You guys can get a train and come in by yourselves. They had dumped so much food in 55-gallon drums from airplanes that we had plenty to eat. You would be in the latrine eating and eliminating at the same time and then you would go back and get some more to eat."

-- Wilayto.

"It's sort of a strange let down. Actual freedom takes so long to occur. You wonder, is it true? It's not done in a rapid or efficient fashion. We were just wasted, abandoned creatures. They flew us down to the Philippines. I understand one plane crashed and lost everyone. The one I was on had two engines go out in the dark of night. When you heard them shutter, you said, 'Oh my God. I've gotten this far. How can this happen?' It's a frightening sound, if you're over water especially. I asked the crew chief, 'Do you think we can make it?' He said, 'I sure as hell hope so.'"

-- Crowley.

"We got back to the States and they were doing some tests and we wanted to go home, but they wouldn't let us. I got with the guys and said, 'Don't say nothing. Let me take care of it.' So I found out who was in charge and I says, 'I'm just going to let you know as a matter of courtesy, we ain't going to be here tomorrow morning. We were told we're going to be released and we're not going to sit around for a bunch of tests when our home is up that way and we've been away for almost four years.' They gave us our clothes and they got us on a train and they shipped us to the port nearest our home."

-- Stensby.

LONG-TERM HEALTH

"There are some areas of what would be classified as a mental damage. It would be impossible not to have it. Tooth problems. Stomach problems. Arthritis. All kinds of ills. I'm going to be 95 and you don't know how much of what you have is because of age or the damage you were receiving by the body being punished so hard. I still have tremendous pain in my arm, my shoulder, where I caught a lot of clubs."

-- Crowley.

"I had a disability that's pretty hard, see. On the left side of my head, I was hit with the butt of rifles and so forth many times to get me to move or do something. That scarred it. And my short-term memory from that time was nil. I'd go to school and I'd understand everything they said. And when I got back to the cotton-picking barracks, I don't remember a thing they said."

-- Stensby.

"These men had horrific trauma. When they came back, none of them really sought psychiatric help because their generation saw it as a weakness, and when they finally did, they were usually in their 80s or their 90s. The toll on not only the former POW, but his family, his wife, the caregiver was immense. As soon as my father was liberated, he met my mom and he knew her two weeks before he proposed. That was common. I think it was their way of trying to get back to normal as fast as they could. A lot of those early marriages did not succeed. Young women just had no clue what they were dealing with. A lot of the men drank. Often the men would be violent. They didn't have to be violent during the day, but their nightmares, their dreams. A lot still have nightmares on their deathbeds."

-- Thompson.

(Editor's Note: Quotes have been condensed and edited for clarity. All of these veterans survived the sieges on Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines. The link to that story is below. Stensby, Peterson and Wilayto have passed away since recording their oral histories.)

Related Links:

Experiencing War, Prisoners of War: Stories from the Veterans History Project

After Pearl Harbor, Soldiers held out for months against Japanese invasion of Philippines

Social Sharing