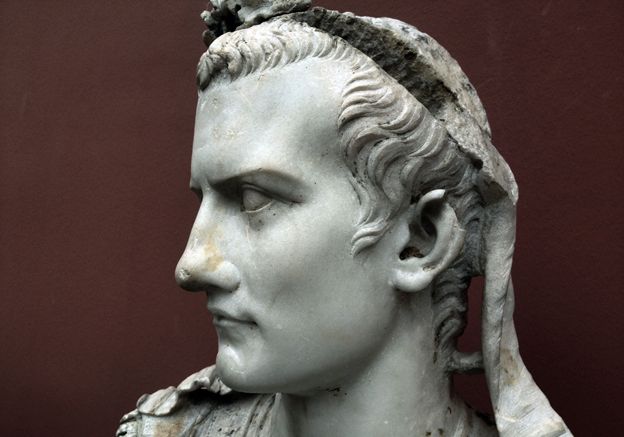

Viewpoint: Does Caligula deserve his bad reputation?

- Published

The Roman emperor Caligula's name has become a byword for depraved tyranny, used as a popular benchmark for everyone from Idi Amin to Jean-Bedel Bokassa. But was Caligula really mad and bad, or the victim of a smear campaign, asks historian Mary Beard.

Our modern idea of tyranny was born 2,000 years ago. It is with the reign of the Caligula - the third Roman emperor, assassinated in 41 AD, before he had reached the age of 30 - that all the components of mad autocracy come together for the first time.

In fact, the ancient Greek word "tyrannos" (from which our term comes) was originally a fairly neutral word for a sole ruler, good or bad.

Of course, there had been some very nasty monarchs and despots before Caligula. But, so far as we know, none of his predecessors had ever ticked all the boxes of a fully fledged tyrant, in the modern sense.

There was his (Imelda Marcos-style) passion for shoes, his megalomania, sadism and sexual perversion (including incest, it was said, with all three of his sisters), to a decidedly odd relationship with his pets. One of his bright ideas was supposed to have been to make his favourite horse a consul - the chief magistrate of Rome.

Roman writers went on and on about his appalling behaviour, and he became so much the touchstone of tyranny for them that one unpopular emperor, half a century later, was nicknamed "the bald Caligula".

But how many of their lurid stories are true is very hard to know. Did he really force men to watch the execution of their sons, then invite them to a jolly dinner, where they were expected to laugh and joke? Did he actually go into the Temple of the gods Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum and wait for people to turn up and worship him?

It is probably too sceptical to mistrust everything that we are told. Against all expectations, one Cambridge archaeologist thinks he may have found traces of the vast bridge that Caligula was supposed to have built between his own palace and the Temple of Jupiter - so it was easier for him to go and have a chat with the god, when he wanted.

So the idea that Caligula was a nice young man who has simply had a very bad press doesn't sound very plausible.

All the same, the evidence for Caligula's monstrosity isn't quite as clear-cut as it looks at first sight. There are a few eyewitness accounts of parts of his reign, and none of them mention any of the worst stories.

There is no mention in these, for example, of any incest with his sisters. And one extraordinary description by Philo, a high-ranking Jewish ambassador, of an audience with Caligula makes him sound a rather menacing jokester, but nothing worse.

He banters with the Jews about their refusal to eat pork (while confessing that he himself doesn't like eating lamb), but the imperial mind is not really on the Jewish delegation at all - he's actually busy planning a lavish makeover for one of his palatial residences, and is in the process of choosing new paintings and some expensive window glass.

But even the more extravagant later accounts - for example the gossipy biography of Caligula by Suetonius, written about 80 years after his death - are not quite as extravagant as they seem.

If you read them carefully, time and again, you discover that they aren't reporting what Caligula actually did, but what people said he did, or said he planned to do.

It was only hearsay that the emperor's granny had once found him in bed with his favourite sister. And no Roman writer, so far as we know, ever said that he made his horse a consul. All they said was that people said that he planned to make his horse a consul.

The most likely explanation is that the whole horse/consul story goes back to one of those bantering jokes. My own best guess would be that the exasperated emperor one day taunted the aristocracy by saying something along the lines of: "You guys are all so hopeless that I might as well make my horse a consul!"

And from some such quip, that particular story of the emperor's madness was born.

The truth is that, as the centuries have gone by, Caligula has become, in the popular imagination, nastier and nastier. It is probably more us than the ancient Romans who have invested in this particular version of despotic tyranny.

In the BBC's 1976 series of I Claudius, Caligula (played by John Hurt) memorably appeared with a horrible bloody face - after eating a foetus, so we were led to believe, torn from his sister's belly.

This scene was entirely an invention of the 1970s scriptwriter. But it wrote Hurt into the history of Caligula.

The vision even spread to comics. Chief Judge Cal in Judge Dredd was based on Hurt's version of the emperor - and appropriately enough Cal really did make his pet goldfish Deputy Chief Judge.

But if the modern world has partly invented Caligula, so it also has lessons to learn from him and from the regime change that brought him down.

Caligula was assassinated in a bloody coup after just four years on the throne. And his assassination partly explains his awful reputation. The propaganda machine of his successors was keen to blacken his name partly to justify his removal - hence all those terrible stories.

More topical though is the question of what, or who, came next. Caligula was assassinated in the name of freedom. And for a few hours the ancient Romans do seem to have flirted with overthrowing one-man rule entirely, and reinstating democracy.

But then the palace guard found Caligula's uncle Claudius hiding behind a curtain and hailed him emperor instead. Thanks to Robert Graves, Claudius has had a good press, as a rather sympathetic, slightly bumbling, bookish ruler.

But the ancient writers tell a different story - of an autocrat who was just as bad as the man he had replaced. The Romans thought they were getting freedom, but got more of the same.

Considering what happened then, it's hard not to think of the excitements and disappointments of the Arab Spring.

Caligula with Mary Beard is broadcast at 21:00 BST on 29 July 2013 on BBC Two