Listen to this article 5 min

For years, environmentalists have been protesting plans for a new quarry next to Umstead State Park – causing challenges for Wake Stone Corp., a Knightdale company run by a family that says they didn’t see the controversy coming.

Ask Sam Bratton, CEO of Wake Stone, and he’ll tell you the business has been a “good neighbor” to the park – so much so that when he signed the lease for land – located between the park and Intestate 40 -– to operate a second quarry in March 2019, he thought permit approval would take six months to a year.

Bratton knows not everyone likes the idea of a quarry crushing rock next to a state park. But where else should it go, he asks.

“You have to have construction, you have to have aggregate materials to have construction, so you’re going to have to have this,” Bratton said. “Is it better to say that this ought to be in somebody else’s backyard … because they’re less important than Umstead State Park? We have an existing site, we’re just trying to expand it.”

Recently, the company scored a major win. The initial rejection of its application for a mining permit was overturned by the state Office of Administrative Hearings. While the decision is being appealed, Wake Stone sees it as validation and is moving ahead with work to get the new quarry up and running.

On a recent Wednesday, Bratton took Triangle Business Journal on a site tour of the current Triangle Rock Quarry and the area he hopes will house the expansion to keep the operation going for the next few decades.

Bratton said that Wake Stone’s plan will preserve natural resources for the long term – not tear them down. When the pit is up and running it will support 25 jobs – not including customers and truck drivers moving and using the rock.

Wake Stone is leasing the land, a 105-acre site known as the Odd Fellows Tract – from the Raleigh-Durham Airport Authority. Lease payments over the 25-year term (which has the option to be extended) would mean “minimum” annual payments of $8.5 million to RDU. The airport would be entitled to 5.5 percent of the proceeds of the stone extracted from the site – which, according to to the Airport Authority, could total $20 million to $25 million. Much of that will go toward major infrastructure projects at the airport.

Getting to the site

The quarry site is through a mess of trees – not accessible by the pickup truck Bratton uses along the twisty roads surrounding the 42-year-old quarry pit.

Bratton pulled out a black metal spray can. “I hate ticks,” he said, letting the chemical fog over his khakis before stepping through the brush.

It’s not a long walk to Crabtree Creek from the gravel road overseeing the pit. It’s through high, thick grass and thorns – so dense and full of life that we have to sweep caterpillars off our pants back at the truck. It’s steep, leveling out into brown leaves and trees. It’s a straight shot to the edge of the embankment overlooking the brown waterway.

“The bridge will be here,” said Cole Atkins, Wake Stone’s head geologist and environmental supervisor, pointing to the tree-lined bank. Atkins, the main author of the firm’s permit modification application, pulls out a large white survey map to get his bearings.

The bridge – already under design – will transport trucks from the new pit to the legacy quarry.

As the pit is being dug out, “the overburden,” the earth currently over the rock, will be transported to the legacy quarry, which will also collect stormwater runoff.

“It’s pretty unique to have an exhausted pit next to where you’re developing a new pit where you can move the dirt,” Bratton said. And while fill will be available for grading projects around the Triangle, the proximity of that pit means digging won’t be limited by what dirt the quarry can move out to other projects.

The legacy operation – the Triangle Rock Quarry that has been operating since the early 1980s – will also house the processing, stockpiling and sales operation for the new pit.

Atkins said that if a new quarry operator had come in, it would be much more impactful to the site, as the crushing operation would have to be built from the ground up. With the existing infrastructure, the impact will be less than if it all had to be built from scratch, he said.

But going after the legacy operation is one tactic those opposed to the new quarry are trying in court.

They’ve filed litigation over the so-called “sunset clause," a term quarry officials say is made up. The phrase refers to an agreement Wake Stone signed in 1981 that would have the rock crusher turning its existing Triangle Rock Quarry over to the state after either 50 years or 10 years after quarrying operations cease, “whichever is sooner.”

Wake Stone secured modifications to its original permit in 2018, changing the wording to “whichever is later.”

Bratton has consistently argued that it’s minutiae that changed over the years – despite what others have said.

He said the intention had always been to operate for 50 years or whenever mining completes. But it's a moot point, Bratton said, as the new permit modification gives the quarry a second pit to continue the mining.

Wake Stone brought the wording to regulators’ attention in 2011, and pushed harder when it set its sights on the quarry expansion. “By 2017 we knew [expansion] was a possibility because we had talked to (RDU Airport officials), we needed to get it right,” Bratton said.

Atkins insists the change was to “clean up” the language, correct typos and shift terminology around buffers that had changed through multiple renewals over the years. The original permit marked buffers from the property line, the center of the creek, he said. Over the years, the language changed through renewals to mark the buffer from the top of the bank. Both men say the language modifications weren’t nefarious.

“It was us getting everything consistent with what was originally agreed upon,” Bratton said. “There was no agenda. It was just changing the wording. … How it got from later to sooner, we don’t know. We don’t know, but we know it was incorrect.”

If a court rules that Wake Stone must stop mining in 2031, “everything would stop,” Bratton said.

“But there’s not a chance that it will be successful,” he said of the sunset clause suit. “This has been made into an issue that is not an issue … and we have a new permit, so any previous permits don’t matter.”

While Bratton’s operation scored a major victory in getting the permit rejection overturned (and a court order that it be paid more than $878,000 in legal fees) – he knows there will be appeals.

But Bratton has time. The existing pit still has a few years of aggregate left to mine. And the planned bridge over Crabtree Creek needs to be fully designed.

The opposition

But as fervently as Bratton believes the permit should go through, detractors say the opposite – in petitions, on signs and in courtrooms.

Jean Spooner, chairwoman of the Umstead Coalition, said that she’s confident the courts will ultimately side against the permit.

She said any attempt to compare what’s being proposed to the existing quarry isn’t relevant. The two sites have completely different topographies, Spooner says.

“There’s nothing comparable to what they are currently proposing in their current pit. It’s just nuts," she said.

Bratton said the location of the quarry is ideal. In terms of aggregates, there’s 10 tons per capita annual consumption in Wake County. The quarry will likely produce just a tenth of that, its rock used primarily within a 5-mile radius.

What's next

If the litigation stops and the permits all stand, it would take about two years for the bridge and infrastructure to be placed so that Wake Stone can start harvesting rock. Roadway improvements have to be made. The property needs to be timbered, erosion control measures installed and a security fence will need to be erected in certain places.

A trek to the Reedy Creek roadside entrance of the property shows why. Cyclists are still using RDU-controlled property – airport officials say they're trespassing. The bike trails are still evident in the dirt. A large tree that had been blocking the site entrance has been cut away with chainsaws – and not by Wake Stone. The fact that those using the unsanctioned trails were bold enough to bring chainsaws onto the property shows the need for fencing measures, Wake Stone officials said.

Bratton said he’s been trying to engage with the opposition – hosting groups from both the Umstead Coalition and Triangle Off-Road Cyclists in the conference room of the Triangle Rock Quarry, taking them on tours of the site.

It was Wake Stone’s idea to lease 150 acres to the county for mountain biking trails, he said.

But the opposition continues.

The company has made some changes at the suggestion of park proponents. Initially a rock crusher was supposed to be on the other side of the creek, but there was concern that the elevation in the area could allow the noise to travel to the park. So Wake Stone “agreed,” keeping the crushing operation in the legacy campus.

It’s putting up a sound wall to protect the park when it hauls materials across the creek.

But noise has been a consistent concern for those affiliated with the park – and figuring out how to define the impact has been a challenge.

Bratton insists it’s hard to model, as there’s already noise – from I-40 and planes flying overhead. And he said the most trafficked area of the park is close to the existing operation – where Wake Stone didn’t receive complaints until it announced its intent to expand.

“There were no problems until we announced that we were going to apply for a modification to expand the quarry, then all of a sudden we became a bad actor,” he said (it's a statement the Umstead Coalition disagrees with, pointing to a landslide impacting Crabtree Creek in the 1990s).

Bratton sees some positives – primarily the fact that expanding an existing operation instead of starting a new one mitigates the environmental impact.

Bratton thinks the opposition is coming from a very vocal minority.

“I don’t think the residents of Wake County as a whole are very engaged in this issue at all,” he said.

That’s as both North Carolina State Parks and the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources have opposed the expansion permit.

“The problem is, not liking something is not a denial criteria,” Bratton said.

Protecting the legacy

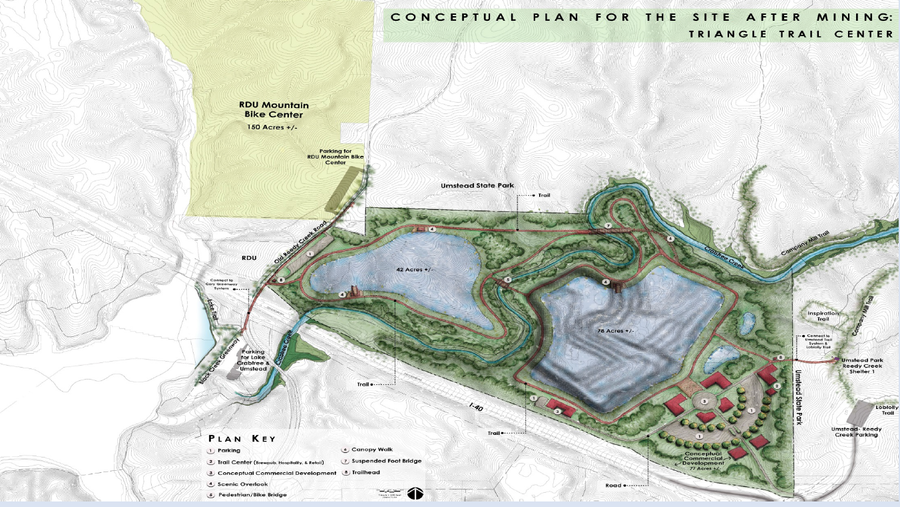

After a few decades of mining, the land will be used for recreation – a fact Bratton repeats on each site tour. Quarrying the property prevents other forms of industrialization, protecting the area for the future, Bratton said.

“Umstead Park is going to be here forever … once the quarry is completed, it will become a recreational amenity adjacent to Umstead that will enhance Umstead,” he said.

It's something Spooner calls "insulting."

“It’s hard to imagine what recreational facilities can fit in a measly, tiny, 25 feet of setback,” she said.

Bratton, the youngest of seven children, lives a mile from the house he grew up in. He watched his father and brothers lead the company – and now it’s his turn.

Someday, one of his nephews will take over.

Bratton remembers watching slideshows on the weekends from the couch when he was six years old- his father booting up a projector with carousel on top, showing his family the pit they were constructing. He remembers wanting to be a part of it – “it was a dream of my father’s.”

It’s his family’s legacy, he said. But park proponents say it’s their legacy too.