The thing that strikes me most about the female gaze is that it is a rallying call, not only for women but for all the perspectives that have been missing throughout history in art and culture, where the male viewpoint has dominated. The concept of the female gaze is not new – women have always been active gazers – but the term is useful today to articulate an age-old absence in all forms of art, fashion and culture.

And yet it means so much more than this. The term emerged in the mid 1970s, out of an essay by the feminist film critic Laura Mulvey dealing with the superficial treatment of female characters in cinema. Then it mostly percolated in academic and radical feminist circles until it made its way into the vernacular in the 2010s.

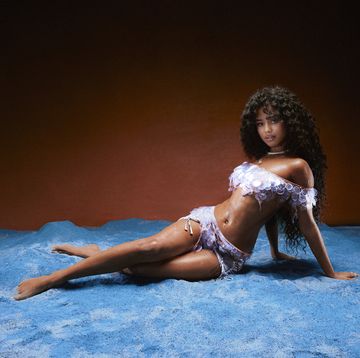

I first encountered the term on the internet, used to describe a movement of female artists, among them Juno Calypso and Maisie Cousins, who were using photography to explore their own, and sometimes other women’s, bodies. Their dazzling visions of different aspects of being a woman felt redemptive and relatable.

A subtle shift in observing snowballed into an avalanche: by the time I published my book on the female gaze, Girl On Girl, in 2017, the movement had expanded across the arts, fashion, culture and beyond. More than a counterbalance to the male point of view, the female gaze has driven conversations on diversity, inclusion, equity and power. The contributions of women of colour, trans women and differently abled women have updated the 1970s idea of the female gaze as our understanding and experience of woman-hood evolves. Soft, supple, and spacious, the female gaze continues to be reinterpreted and remoulded, the same way as our understanding of what constitutes ‘female’ is ever-changing.

The female gaze has also prompted female-centred narratives in cinema and TV, everywhere from the live action versions of the The Little Mermaid, starring Halle Bailey, and Barbie – where the doll is reimagined by a diverse cast of women including Hari Nef, Issa Rae and Sharon Rooney – to era-defining sheroes like Succession’s Shiv Roy, Queen Charlotte or Jennifer Coolidge’s Tanya in White Lotus. The allure of these characters is complex, as disturbing as it is compelling; far from the passive, one-dimensional depictions of women on screen that Mulvey railed against.

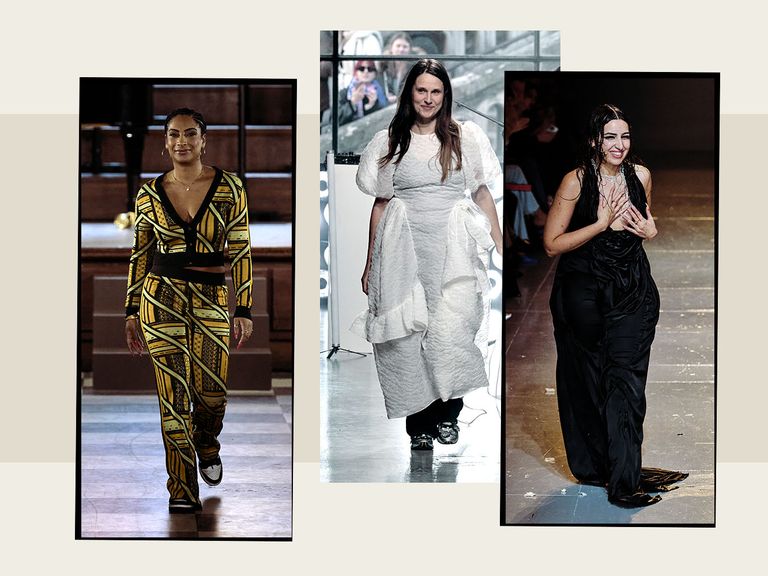

The age of the female gaze heralded a new era in fashion, too, with women at the creative helm of Dior and Chanel. Meanwhile, Balenciaga, Loewe, Saint Laurent and Christopher Kane blaze a trail with female CEOs. Intertwined with this is the groundswell of independent women designers and others working behind the scenes, lodestars for design for real women – not the image of a woman. The effect of this flows in all directions: the female gaze is not only about what we see, but what we wear, the spaces we inhabit; it’s about the day-to-day details and rhythms that have us in mind.

Do women see the world differently? I still don’t have a straightforward answer. But I believe we should continue to covet the female gaze, to insist on it as a synecdoche for women’s creativity and presence. The female gaze keeps us vigilant to oppression and patterns of domination. To notice the unnoticed and find beauty in unexpected places. To care for those who are neglected. To boldly envision worlds we haven’t yet seen. To honour the rich wells of our imagination. It is a conscious, continued, collective effort to recognise and celebrate women in all their glorious forms.