1900 book cover of Heriberto Frias’ Historia de los dos volcanes

1900 book cover of Heriberto Frias’ Historia de los dos volcanes

Book cover from Frias, Heriberto. Historia de los dos volcanes: Corazon de Lumbre y Alma de Nieve. Mexico: Maucci Hermonos, 1900.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

On 8 November 1935, Mexico’s president, Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940), established the Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl National Park, the first of nearly forty national parks created during his term. Mostly scattered across the central highlands and containing mixed pine and fir forests, these parks typified the natural and social landscape surrounding the capital, Mexico City.

This first decree gave many justifications for the park, including scientific conservation, afforestation, climatic stability, tourism, and promoting a “living museum to nature.” Most importantly, it articulated federal authority over land that had long been claimed by resident indigenous and mestizo communities or private hacendados and entrepreneurs. This assertion of federal power came from the first social revolution of the twentieth century that strove to represent the best interests of “Mexico for Mexicans” by integrating desires for capitalist development with the recognition of rural people’s rights to land and resources (fields, forests, and waters). This radical claim embedded within a national park decree characterized the moment in which Izta-Popo National Park was created and Mexico’s innovative approach to conservation.

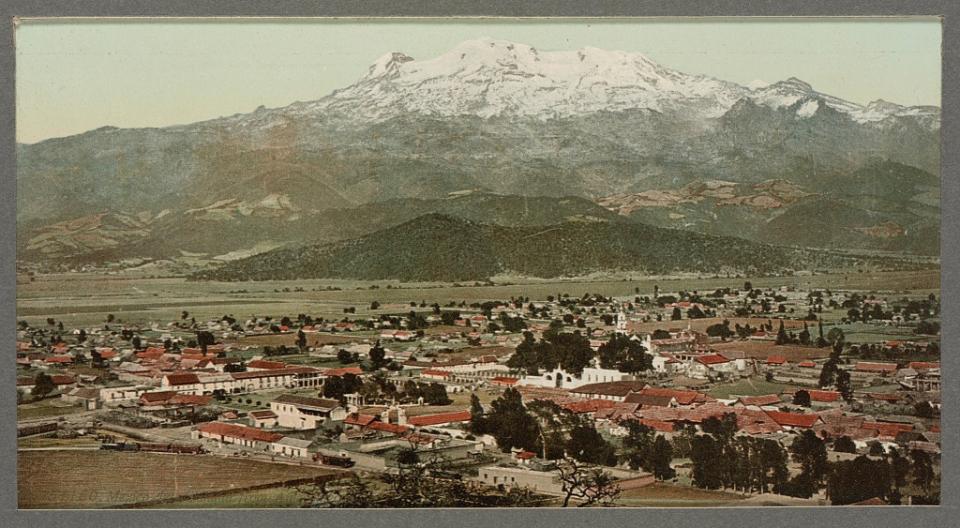

Photo by William Henry Jackson of the Iztaccíhuatl volcano from Amecameca (between 1884 and 1900)

Photo by William Henry Jackson of the Iztaccíhuatl volcano from Amecameca (between 1884 and 1900)

Photography by William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Click here to view LOC source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Like other countries, in the late nineteenth century Mexico began to feel both the social and the environmental effects of forest loss, but it was not until the 1930s that environmental conservation meaningfully entered national policies. National parks formed a keystone of conservation legislation during the first stable, elected government after years of revolutionary fighting. By the end of Cárdenas’s term in 1940, Mexico had more parks than any other country in the world. These parks testify to a particular style of conservation—one that occurred alongside urban development, privileged local use, and invoked flexible scientific principles. The parks came to represent these values in the give-and-take of social reconstruction and as part of a revolutionary project that embraced methods of retaining village life while positioning Mexico as a modern nation.

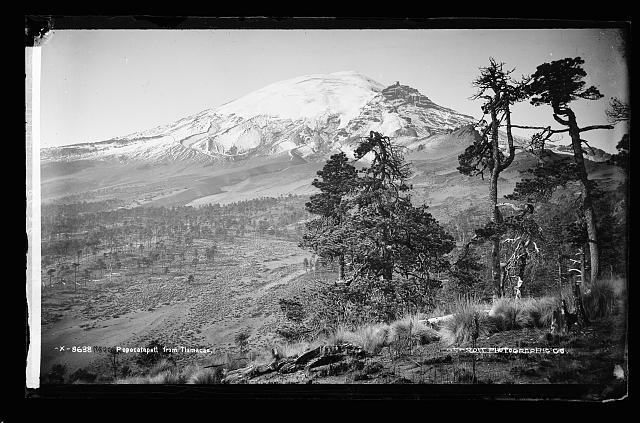

Photo by William Henry Jackson of the Popocatépetl volcano from Tlamacas (between 1880 and 1897)

Photo by William Henry Jackson of the Popocatépetl volcano from Tlamacas (between 1880 and 1897)

Photography by William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Click here to view LOC source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Izta-Popo Park itself contains an interesting assortment of natural, social, and historic landscapes characteristic of the Mexican countryside and the political heritage of colonialism. The park’s namesake volcanoes, Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl, are known by Nahuatl names that anthropomorphize the mountains as a sleeping woman and a smoking warrior. Popular myths explain these figures as lovers separated by war and catastrophe and finally reunited immortally on the skyline. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés laid eyes for the first time on the impressive Aztec (Mexica) city of Tenochtitlán (today’s Mexico City) from a pass between the two mountains. Now known as the Paso de Cortés, this pass in the park’s center was the portal through which the two worlds encountered each other.

Popocatépetl (the “smoking warrior”) from the “feet” of Iztaccíhuatl (the “sleeping woman”)

Popocatépetl (the “smoking warrior”) from the “feet” of Iztaccíhuatl (the “sleeping woman”)

All rights reserved © 2005 Emily Wakild.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Today the park retains vestiges of Mexico’s past environments. Despite centuries of use, vibrant stands of forests crowd the flanks of the mountain slopes. Animals, like the zacatuche, or alpine rabbit, and the gato montés, or Mexican bobcat, persist. Popo continues to rumble and send plumes of volcanic ash skyward, paralyzing air travel or provoking evacuations in surrounding communities. Izta stewards the country’s few remaining glaciers and hosts hundreds of climbers every year. But the symbolism of the park—a compromise between social reform, revolutionary justice, and scientific management—looms large as both an example and a warning for parks created with human use at their core.

How to cite

Wakild, Emily. “Resources and Revolution: Mexico’s Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 15. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5607.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2013 Emily Wakild

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Boyer, Christopher R., and Emily Wakild. “Social Landscaping in the Forests of Mexico: An Environmental Interpretation of Cardenismo, 1934–1940.” Hispanic American Historical Review 92, no. 1 (February 2012): 73–106.

- Bray, David Barton, Leticia Merino-Pérez, and Deborah Barry, eds. The Community Forests of Mexico: Managing for Sustainable Landscapes. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005.

- Craib, Raymond. Cartographic Mexico: A History of State Fixations and Fugitive Landscapes. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Donnet, Beatriz. Leyendas del Popo y algo más. Mexico: Lectorum, 1999.

- Tortolero Villaseñor, Alejandro, ed. Entre lagos y volcanes: Chalco, Amecameca, pasado y presente. Vol. 1. México: El Colegio Mexiquense, 1993.

- Wakild, Emily. “‘It Is to Preserve Life, to Work for the Trees’: The Steward of Mexican Forests, Miguel Ángel de Quevedo, 1862–1948,” Forest History Today, Spring/Fall 2006, 4–14. View article

- Wakild, Emily. Revolutionary Parks: Conservation, Social Justice, and Mexico’s National Parks, 1910–1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2011.