Historical fiction is suddenly everywhere. It’s on the bestseller list, in college classrooms, and probably on the lap of the woman sitting next to you on the train. A genre that at one point felt maligned and boring—neither serious nor sought after—has undergone a full-on transformation. In just the past few months, some of the most anticipated new releases by contemporary literature’s most beloved authors have been historical, including Lauren Groff’s The Vaster Wilds, Zadie Smith’s The Fraud, James McBride’s The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, and Jesmyn Ward’s Let Us Descend.

Evidence of historical fiction’s resurgence is everywhere: three out of five works of fiction nominated for this year’s National Book Award are historical. Hernan Diaz’s Trust won the Pulitzer Prize. New and anticipated film and TV adaptations like Lessons in Chemistry, Pachinko, All the Light We Cannot See, and Daisy Jones and the Six (alongside the enduring popularity of period dramas like Bridgerton) show an ever-widening interest in the genre, taking the form of everything from serious literary study to guilty pleasure.

Just as science fiction, once dismissed as merely “popular,” has enjoyed increasing acceptance as literary, historical fiction has become widely critically recognized. Like science fiction, historical fiction can speak to the present moment without necessarily responding to the most recent news headline or Twitter feud. It can also be a means of formal experimentation or inspiring empathy and identification with characters over time. Writers like Groff and Smith use historical settings to rewrite history and to expand our understanding of who and what is at the heart of the stories we already know. And, increasingly, they do so without being condemned to the back shelves of the bookstore.

While science fiction has long been beloved by readers, it has historically been shunned by critics, university writing programs, and award-granting institutions. Margaret Atwood, seeking to set herself apart in her 2004 essay collection, Moving Targets, claimed that none of her work was science fiction. She preferred the term “speculative,” which seemed closer to serious. Ursula K. Le Guin, reviewing Atwood’s Year of the Flood for The Guardian a few years later, called out the misclassification, one she claims Atwood made “to protect her novels from being relegated to a genre still shunned by hidebound readers, reviewers, and prize-awarders.”

It’s no wonder why. In his 2003 review of Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, New York Times critic Sven Birkerts wrote, “I am going to stick my neck out and just say it: science fiction will never be Literature with a capital 'L.'” This was not atypical thinking at the time.

The debate hasn’t aged well. In the intervening years, Atwood and Le Guin’s work has been read, reviewed, and prized beyond belief. Their acclaim has helped pave the way for a new generation of writers like Emily St. John Mandel, Sequoia Nagamatsu, and Ted Chiang, whose work has been described as “speculative” and “science fiction” interchangeably, all while being awarded, cited on bestseller lists, and adapted for film and television.

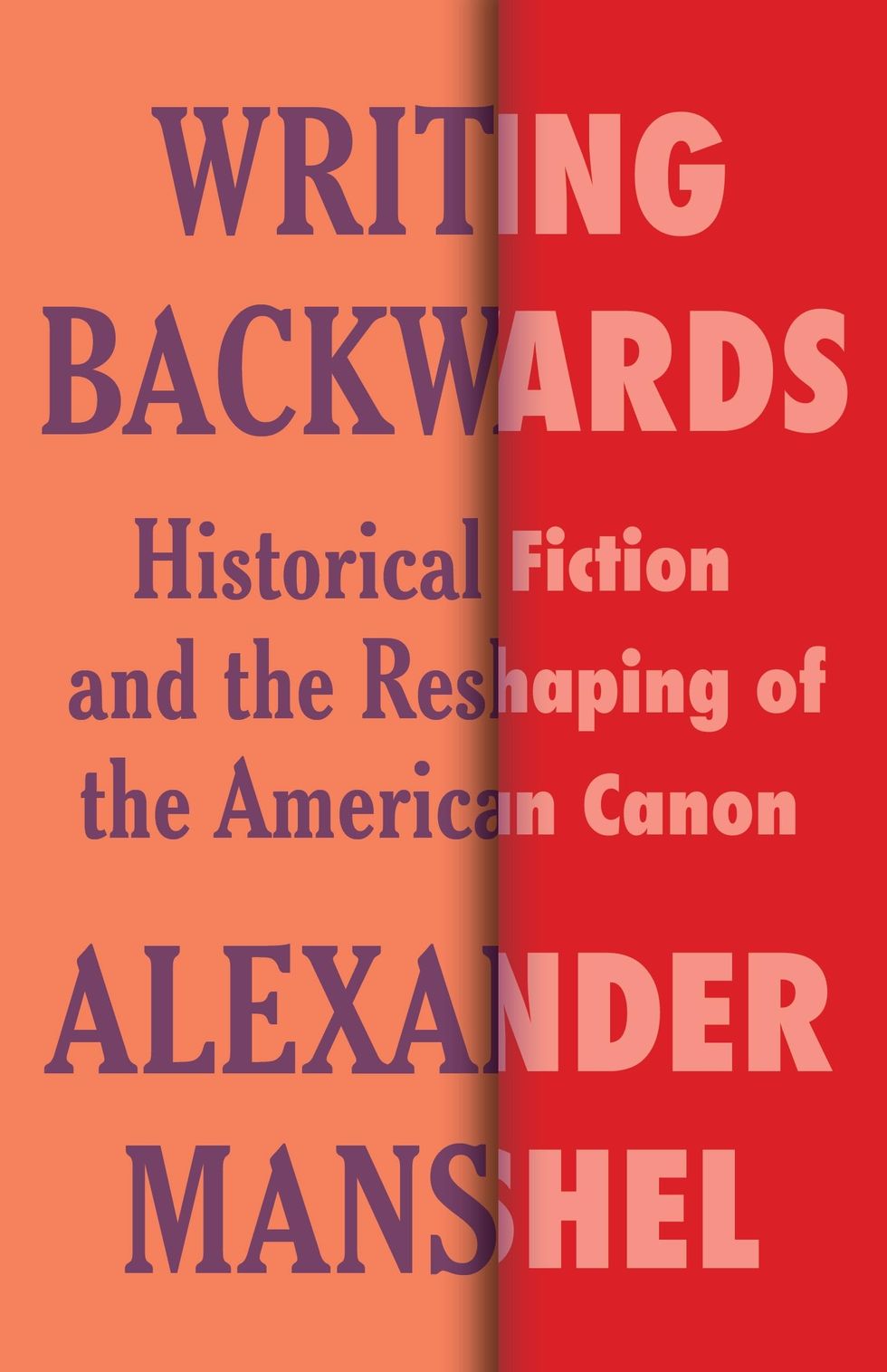

Alexander Manshel’s new book, Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon, out November 21, tells a similar (albeit longer) story about historical fiction’s transformation from denigrated to celebrated. Reading Manshel's account, I had a realization that a moment in Nathan Hill’s new novel, Wellness, summed up fully. One of Hill’s protagonists, Elizabeth, looks up to realize that summer has turned into fall, seemingly all at once. It must have happened gradually, but she ignored the signs until they were undeniable.

People use foliage trackers to determine when they can see the changing leaves at their most colorful and vibrant. By all measures, historical fiction has reached what such a tracker would categorize as peak conditions.

Wellness is itself a sign of this culmination. It is a New York Times bestseller and an Oprah’s Book Club pick. It has received glowing reviews from major literary and popular outlets, recently appearing as a recommendation on the Today Show. It is also a serious book—a weighty tome of 600 pages. Moving back and forth through the literary past to today, tracing the lives of two married people, it looks at prominent and pressing issues of the present, like how so much of what we read and believe is determined by algorithms. For Hill, the past becomes a tool to look at how people succumb to and are changed by these contemporary phenomena.

Critics appreciate the ambitious nature of such a project, and readers of all kinds are drawn to books that follow families over time. Multi-generational family sagas like Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing enjoy both literary acclaim and widespread popularity, prescribed by university professors and book clubs alike.

Reading Pachinko, the story of a young woman named Sunja and her family during the Japanese occupation of Korea and onwards to the present, it’s impossible not to become invested in the family’s fate. Knowing their interwoven origins and backstories makes them all the more real—especially at a time when social media and literature have popularized psychological thinking, and we view people’s early lives as determining so much of who they are.

These sprawling narratives superimpose a family’s story onto history, allowing one to amplify the other—personalizing historical moments while also elevating familial events to the same level of importance. I know I am not alone in having wept as Sunja’s family expanded and contracted over the course of generations.

Kristin Hannah’s novels represent another side of the same coin. One of today’s most popular writers, although not necessarily known as a literary one, Hannah has an uncanny ability to reduce readers to tears. Review after review of her more than twenty novels (the majority of which are historical fiction) include descriptions of puffy, tear-ravaged faces or warnings to keep a box of Kleenex handy.

The books are also loved, read widely, and consistently awarded prizes by popular outlets. The Nightingale, a shattering World War II-era romance, won Goodreads' Best Historical Fiction novel and the People’s Choice Award for best fiction in 2015. Its film adaptation is currently in production at TriStar starring Dakota and Elle Fanning. The Great Alone, published in 2018, tells the difficult story of a Vietnam veteran’s return to his family. A changed man, he moves his wife and daughter to a remote area of Alaska, where the realities of his condition are revealed. It became an instant New York Times #1 bestseller—as did The Four Winds, a Depression-era dustbowl drama that makes the Grapes of Wrath seem almost hopeful. Firefly Lane, another sometimes devastating novel following the friendship of two women over three decades, was adapted into a wildly successful Netflix series.

Hannah’s work features characters who are tested by great historical moments. As readers, we become not only invested in their personal histories, but in their place in the history we all share. Seeing them live through pasts we are familiar with adds another layer of recognition and heightens the books’ emotional resonance.

If Hannah’s work gives us emotional insight into why historical fiction enjoys such a large degree of popularity, in Writing Backwards, Manshel helps to explain how it rose to literary preeminence. Manshel traces the genre’s lineage from the start of the 20th century, when it was famously described by Henry James as “fatally cheap” and seen largely in terms of the bodice-ripping we associate with Bridgerton today.

The 1960s and 1970s marked the start of a reversal with postmodernist novels like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. Writing about World War II with a sense of irony, these books challenged mainstream narratives of history and literature at the same time. Their inventiveness and popularity began to bestow a degree of prestige on the genre.

More sweeping changes came in the 1980s and 1990s, when, responding to cultural pressures both inside and outside of school walls, universities and publishers began to more widely recognize the importance of including works by a wider spectrum of people, and to consider the ways the books we read both inform and are informed by history.

Historical fiction filled that role in many ways, becoming a way to elevate histories by and about all kinds of people. During this period and into the present, historical novels have become more and more prominent on university syllabi. They’ve also increasingly been celebrated by prestige-granting institutions like the National Book Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Pulitzer Prize committee.

Toni Morrison’s 1987 book Beloved is a prime example of (and a prime contributor to) this shift. The haunting story of Sethe, a woman who fled slavery but not its memory, Beloved holds many awards and a superlative amount of space on college English class syllabi. According to Manshel, Beloved is both “the single most canonical work of contemporary fiction” and “the contemporary novel book most cited by literary scholars.”

It’s only logical that as the genre gained acclaim, more and more writers turned to historical settings. But there are other factors that explain its widespread appeal. Just as authors and readers have used science fiction to describe the current landscape (as in dystopias like Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, or C. Pam Zhang’s more recent The Land of Milk and Honey), historical fiction is uniquely well-positioned to address contemporary issues without necessarily calling them by name.

When news and social media timelines move so quickly that yesterday’s headline is today’s back page story, zooming out towards the longer arc of history allows readers (and writers) a break from the speed of contemporary life, without retreating from what matters. Genre fiction no longer has that old dusty patina of escapism. These books feel smart, insightful, and timely—and their contents won’t feel dated or irrelevant by the time the author has finished writing.

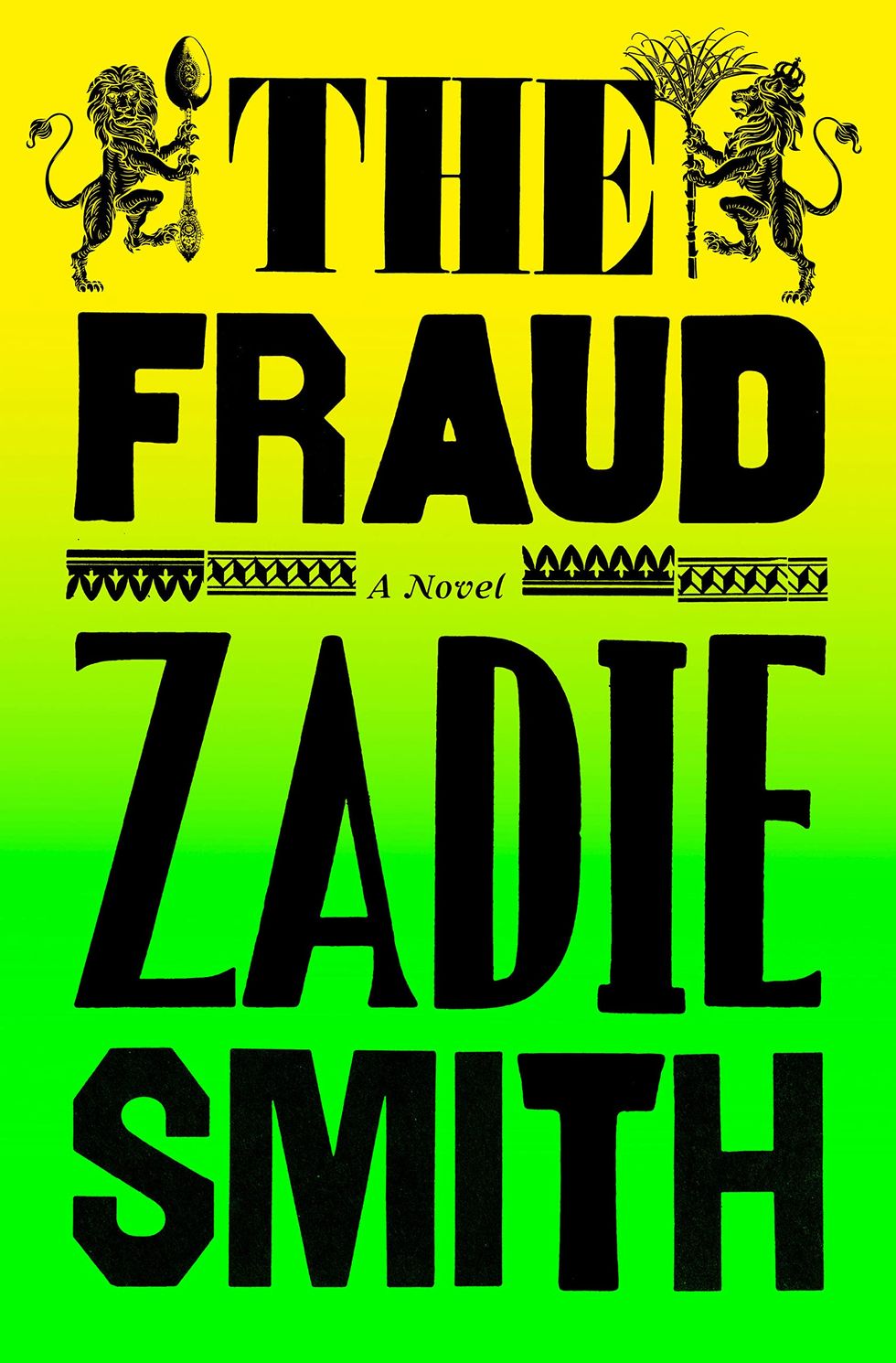

It also doesn’t hurt that distinguished writers like Zadie Smith are producing them. In her latest novel, The Fraud, Smith uses historical setting in expert ways—critiquing historical narrative, while parodying the recent present and the literary profession at the same time.

In the novel, Sir Roger Tichborne, the heir to a fortune, was presumed drowned in 1854. In 1866, a man comes forward and assumes his identity, while almost everyone disputes his claim. The ensuing trial and events surrounding it are a spectacle that inspires the heated populist division (reminiscent of both 2016 Twitter and a football game), with one group of people pointing out the dubiousness of this so-called Sir Roger and another insisting that Sir Roger is the people’s aristocrat, maligned because he does not adhere to their standards. The tone is, to say the least, familiar. As the narrative deepens, we see the ways that almost everyone seems focused on this trivial matter that they view as a major injustice, all while their livelihoods rest on the real horrors of slavery.

While the rest of England is held in rapt attention by the Tichborne saga, William Ainsworth, the historical novelist at the book’s core, is uninterested, focused on what he sees as timeless truths. But, really, instead of confronting the actual problems of his time, he retreats into the past. A thesis of The Fraud, it seems, matches one of mine: it is easy to lose sight of what’s really important in the tumult of what’s popular. Smith expands that to say that it is also easy to lose it in the pursuit of literary fame and big truths. The Fraud, like many of these novels, might show us the way to a middle ground.

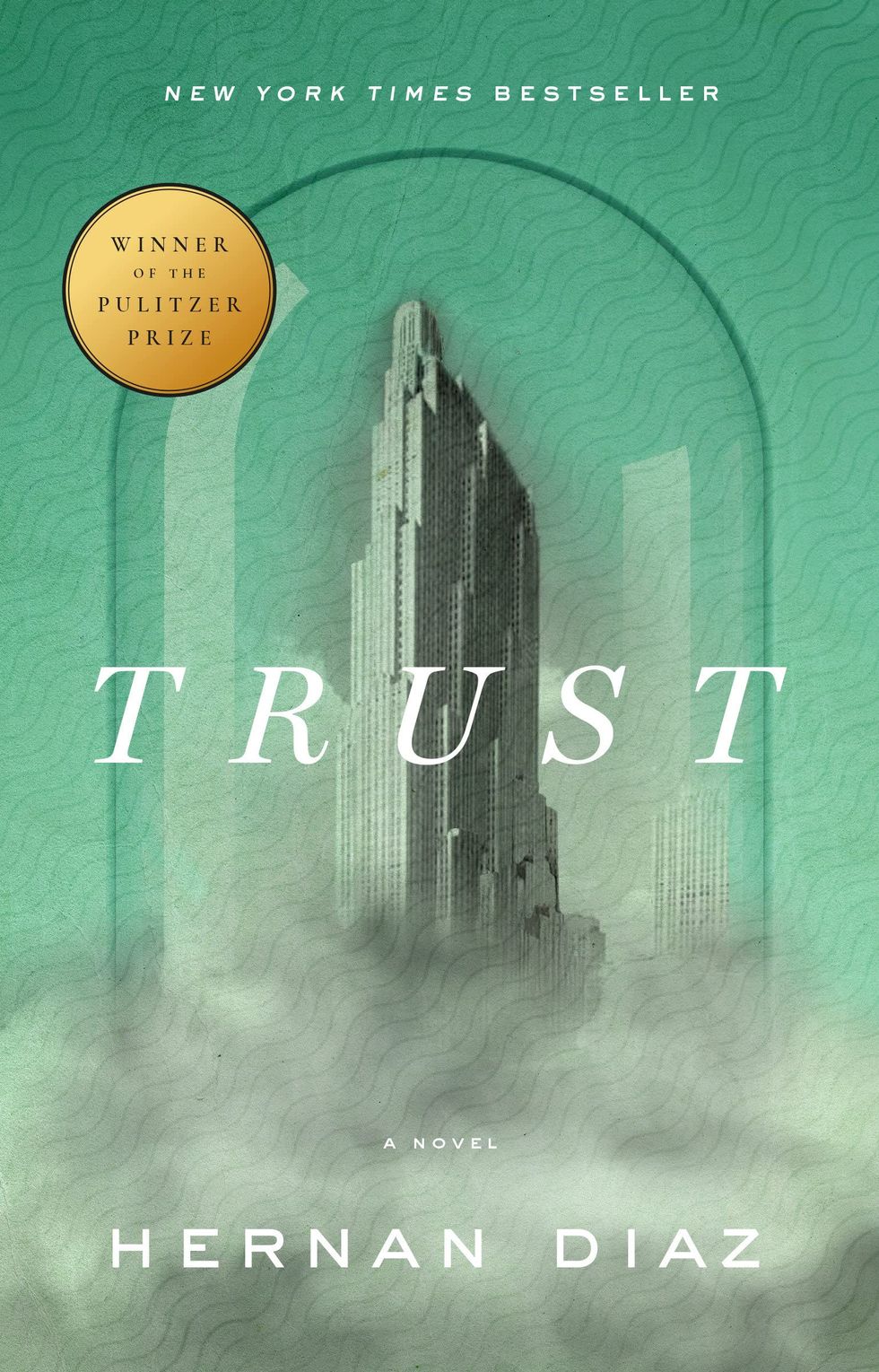

Similarly, Hernan Diaz’s Trust, the 2023 Pulitzer Prize winner, also addresses the present with the past, while highlighting fiction’s own role in the arrangement. Focusing on the relationship between financier Andrew Bevel and his wife, Mildred, leading up to and after the financial crash of 1929 (which Bevel has seemed not only to predict but to profit from), Trust deconstructs the myth of a purportedly “self-made man.”

One section of the book, a parody of the autobiography of a great man, is Bevel’s attempt to mythologize himself. He is a narcissist who writes in elevated terms about his own contributions to his success in a tone that is recognizably Trumpian—here, Diaz offers a critique that both addresses and transcends the present moment.

Trust is about money and power, but also about how those things inform our telling of history, who is empowered to tell it, and how creative works have the potential to rebalance the scales. Moving from grand narratives like Bevel’s, which casts Mildred as a childlike and minor figure, to more and more personal and singular experiences, Bevel’s autobiography is followed by the memoir of the woman who helped write it. Her recollections show the way he lorded over the image of his wife. Finally, we reach Mildred’s own voice in her journals, tilting the focus of everything that comes before.

Trust moves from big histories to Mildred’s own experience. The person who is hinted at and talked about and around becomes realized. Trust’s trajectory illustrates exactly what historical fiction has the capacity to do. It shifts perspectives, recasts history’s leads, and calls mainstream narratives into question.

Lauren Groff’s latest novel, The Vaster Wilds, performs this same recalibration of history. A play on the wilderness narrative or novel of captivity, it is a strange, lonely and, at times spiritual book.

The Vaster Wilds is told entirely through one girl’s claustrophobic perspective as she flees Jamestown, Virginia, traveling alone through unfamiliar woods in the winter. The dialogue is interior, constructed from the voices in her own head and the spirits within and around her. It is a poetic and brutal story of moment-to-moment survival. Both her present in the woods and her flashbacks to life in Jamestown are punctuated by aching and violent hunger.

The girl, taken from an orphanage and brought overseas by her employer, would not even be a footnote in the mainstream retelling of that era. As Groff explained in a recent interview with Esquire, “She would have been overlooked because she’s a servant and a foundling.”

But hers is a lens through which we can clearly view the horrors of colonialism and the brutality of nature, human and otherwise. Instead of glorifying empire and domination, we can see their failures. Pointedly, her experience in nature diverges greatly from the kind of wilderness narratives we are used to—ones that show white men conquering both nature and other people.

Groff’s survival narrative can sit alongside a group of novels challenging and revisiting the western novel, as The New York Times reported on this summer, citing Claudia Craven and Victor LaValle’s books. These works tackle this very traditional narrative structure, retooling old tales to include women, people of color, indigenous, and queer people. This isn’t a new phenomenon (Brokeback Mountain was published in 2005), but it is a trend that’s enduring and expanding.

In the past, publishing a work of historical fiction might have been seen as a left turn for a writer who has published a series of literary books on contemporary themes. Even in 2017, Jennifer Egan’s historical Manhattan Beach was described as a “surprising swerve” in The Atlantic.

But Groff’s career has been a series of these kinds of turns. She wrote an epic story of the unraveling of a hippie utopian community and those who lived on in its wake in Arcadia; followed by a contemporary account of a marriage in Fate and Furies; and then there was the thrilling departure of Matrix, about the 12th-century abbess Marie de France, a poet-nun who, guided by heavenly visions, transforms her priory from a home for starving nuns to a place of power and prosperity. The sweeping trajectory of Groff’s career and the vast amount of acclaim she has received illustrate both the potential and the power of the genre.

For Groff, and for many contemporary authors, historical settings have become a tool and a playground—a way to explore themes that cut across time and challenge the myths that have constructed our view of it. Historical novels of substance and quality are no longer exceptions. They are expected and celebrated, anticipated and awaited—as natural as the changing of the leaves.