The Elfin Palms of Central America and their Cultivation

by Jay Vannini

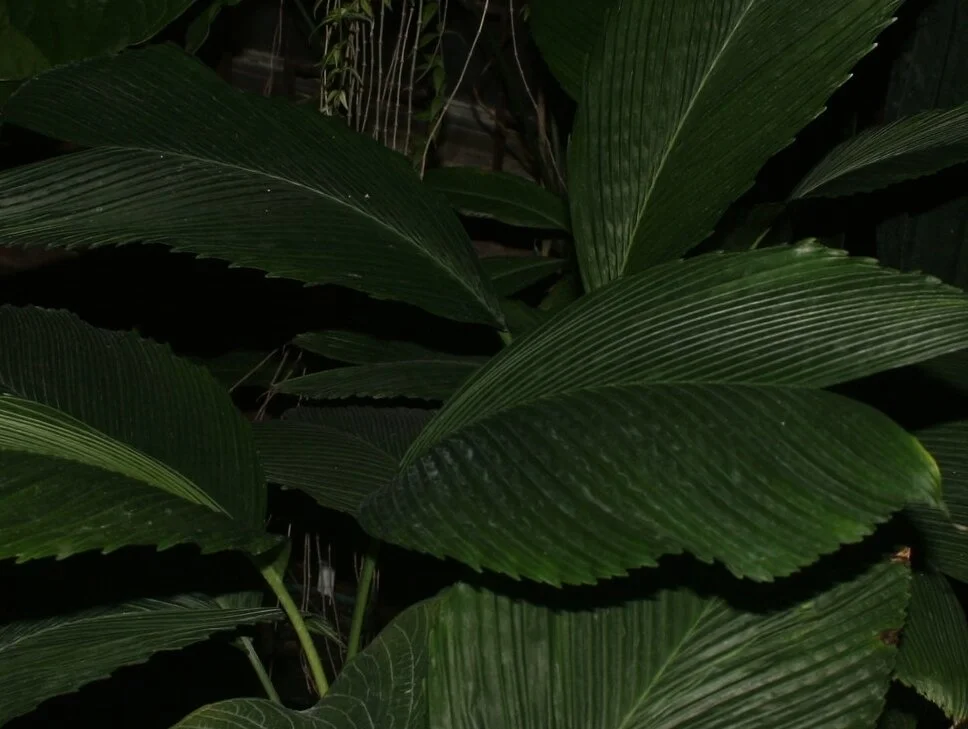

Chamaedorea correae, bifid form, Veraguas, Panamá.

As growing space comes at an ever-increasing premium, many tropical plant collectors are taking a pass on having palms in their collections. While all rare and difficult to find, those shown here are the Crown Jewels of Neotropical palms. With a bit of luck and creative cultivation, many can be adapted to flower and fruit in small spaces.

Elfin palms endemic to the region include members of the genera Chamaedorea, Geonoma, Reinhardtia and Calyptrogyne. A few species extend their ranges from Guatemala north into southeastern México and from Panamá's Darién Province east into northwestern Colombia.

All of these species have made their way into cultivation outside of their home ranges, even the Critically Endangered Chamaedorea piscifolia.

The image bank here is currently dominated by photos taken in situ throughout the region. Over the next few months, more images of cultivated elfin and smaller understory palms will be added, as well as specific recommendations to succeed with these often temperamental beauties in captivity.

Shown above, one of my automated small terraria in California used for establishing delicate Central American and Panamanian palm seedlings from germination boxes at my home prior to moving them into a more conventional greenhouse environment. This is a 24”/60 cm tall unit used as temporary staging only. There are three distinct ecotypes of Chamaedorea tuerckheimii shown here, two in flower (both sexes), several C. verecunda, C. palmeriana and a single Geonoma hugonis. The palms are all planted in soilless growing media in 3.5”/9 cm tall pots. Lighting, ventilation and mist system are all on timers. RO/distilled water is used for charging the mist system.

Taller commercial terraria (39”/1 m), combined with T5 and LED lighting are superb containers for growing many of these tricky palmlet species to flowering size. Several regional species can be grown to full size in these larger Wardian Cases and terraria.

(clicking on or hovering cursor over images here will display additional information and open them in an expanded lightbox).

All images are the author’s, unless otherwise noted.

Geonoma sp., emergent leaf. Lowland rainforest, Limón Province, Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Geonoma hugonis, new leaf, Chiriquí Province, Panamá (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea pumila, Costa Rican highland form, San Jose Province, Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea sullivaniorum, recovering colony of the threatened "blue-gray form", Valle de Antón, Coclé Province, Panamá. This ecotype was collected to near extinction in the early years of the last decade. As far as I am aware, perhaps a handful of living plants persist in foreign and local collections from thousands stripped from nature and suitcase-exported between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s.

The bizarre Chamaedorea tenerrima near type locality, upper Río Polochic valley, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Unfortunately, this particular population was completely lost to deforestation in 2000.

Chamaedorea simplex and juvenile C. carchensis (lower left) growing in riparian cloud forest at the type locality for both, vicinity of Carchá, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Population extirpated due to development earlier this decade.

The delicate and challenging Panamanian velvet palm, Chamaedorea pittieri, Chiriquí Province, Panamá (Image: F Muller).

A beautiful group of salvaged, wild-collected Chamaedorea tuerckheimii growing under native forest cover in a private reserve locate in their recent historical range in Alta Verapaz Department, Guatemala. (Image: W. Elben).

A vividly-marked example of the stained-glass palm, Geonoma eptiolata, western Panamá (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea verecunda, wild Chiriquí highlands, Panamá (Image: F. Muller)

Calyptrogyne allenii, caught in a stray shaft of sunlight, headwaters of the Río Indio, Valle de Antón, Coclé Province, Panamá.

A recently rediscovered enigma, Chamaedorea piscifolia, perhaps one of the world's rarest and last-studied palms, shown in situ in Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea tuerckheimii, F1 "blue form" leaf detail of the potato chip palm, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala.

Chamaedorea scheryi, Santa Fé, Veraguas Province, Panamá.

Chamaedorea stenocarpa, type locality, Cerro San Gil, Izabal, Guatemala (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea castillo montii, type locality, Cerro San Gil, Izabal, Guatemala (Image: F. Muller).

Geonoma ferruginea, Cerro San Gil, Izabal Department, Guatemala (Image: F. Muller).

Despite this species extreme rarity across its natural range in lowland rainforest of northeastern Guatemala and northern Honduras, Chamaedorea brachypoda is a popular dwarf, colonial palm for warm, shady tropical garden corners.

The remarkable medusoid fruits of the newly described, Critically Endangered Chamaedorea vanninii (Cascante & Muller 2020) from Costa Rica. These fruits ripen orange red. (Image: F. Muller).

Portrait of older mature leaf of Critically Endangered Chamaedorea piscifolia with epiphylls (Image F. Muller).

A young Chamaedorea deneversiana, reaching for the sun in lightly-disturbed lowland tropical rainforest understory, Veraguas Province, Panamá.

Chamaedorea cf. sullivaniorum leaf detail, Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Reinhardtia gracilis var. rostrata, one of the dwarf windowpane palms in lowland rainforest, Limón Province, Costa Rica.

Four species of dwarf reinhardtias occur in southeastern México and Central America. The smallest (and rarest) “windowpane” species is the solitary Reinhardtia koschnyana that occurs discontinuously in very wet lowland ecosystems from Honduran Mosquitia southeast into the Darién Province of Panamá and the Province of Antioquia in Colombia. This beautiful miniature palm has so far eluded almost every effort to bring it into cultivation outside of its range countries. Two others are shown below in nature, while the fourth (R. elegans) is a rather challenging palm to encounter in nature in the middle elevation cloud forests of Oaxaca and Chiapas, México, as well as western Guatemala and northern Honduras. The much larger and commonly-cultivated R. latisecta shares habitats with the three lowland species throughout their ranges.

Reinhardtia elegans in nature, Caribbean lowlands of Limón Province, Costa Rica.

Reinhardtia gracilis var. gracilis, Izabal Department, Guatemala.

Reinhardtia gracilis var. gracilior growing as a tall ground cover in a private collection in Guatemala. This species, including three forms, requires deep shade and warm, very humid tropical conditions to thrive.

Although by no means a dwarf palm, Reinhardtia latisecta makes for a wonderful source of low canopy shade for its elfin cogeners.

Mature stained glass palm (Geonoma epetiolata), Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Stained glass palms (Geonoma epetiolata) are a widespread but localized understory premontane rainforest species in Costa Rica and Panamá. They require undisturbed or very lightly disturbed climax forest to thrive, but can be locally abundant under optimum conditions at some remote sites. These heart-breakingly beautiful palms have proven to be very challenging in cultivation outside of Central America and parts of Hawaii. This is one of the most coveted palms originating from the region, and many have been collected from wild populations since its discovery in the 1970s only to die in captivity. They have been artificially produced to F1 in a handful of collections in Queensland, Hawaii and Panamá, but remain very rare in collections worldwide. Wild-collected seed sporadically appears on the market but often shows poor germination. Seedlings are extremely prone to sudden declines and loss until they are about three years old. Outside of fully wet tropical conditions, these palms do best in warm mist chambers charged with pure water and - frankly - overall, require horticultural skills that exceed most growers’ abilities. Stained glass palms are variable across populations, with the highest-color forms originating from the very wet foothill forests of northern Costa Rica and western Panamá. While almost entirely restricted to Caribbean slope localities, they also occur on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide at a few sites in central Panamá. Their closest relative appears to be the somewhat similar, dwarf Geonoma hugonis from cloud forests of the Chiriquí highlands in western Panamá that also has undivided leaves and colorful new growth. This species appears to require cool nights to thrive, but is otherwise less finicky than G. epetiolata.

Emerging leaf detail on mature wild stained glass palm, Geonoma epetiolata, Costa Rica (Image F. Muller).

Leaf detail, cultivated F1 Geonoma epetiolata, California.

Eighteen month-old F1 Geonoma epetiolata seedlings growing in soil-less media, Guatemala.

Geonoma epetiolata, five year-old F1 plants bred in Panamá and growing in cool greenhouse in Guatemala.

Group of F1 Chamaedorea amabilis, part of my reproductive colony grown in Guatemala.

Chamaedorea frondosa colony in Caribbean coastal cloud forest, Cusuco NP, San Idealfonso, San Pedro Sula Department, Honduras (Image: F. Muller).

A group of my F1 Chamaedorea tuerckheimii, Alta Verapaz "blue" ecotype, edging the koi pond of a friend's indoor conservatory in Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Leaf detail, Chamaedorea deneversiana, Veraguas Province, Panamá (Image: F. Muller).

Juvenile Geonoma cuneata subsp. indivisa, Guna Yala Comarca, Panamá (Image F. Muller).

New leaf on a cultivated Chamaedorea pachecoana, a dwarf species resembling a scaled-down C. tenerrima from the western volcanic highlands, Guatemala. F1 flowering-sized plant in a cool tropical California greenhouse. This palmlet has now been bred to F2 both in California and Hawaii.

Chamaedorea tuerckheimii, leaf detail eastern form (Image: F. Muller).

Exceptional form of Chamaedorea dammeriana in lowland rainforest, Limón Province, Costa Rica.

Chamaedorea palmeriana in cloud forest Limón Province, Costa Rica (Image: F. Muller).

Young seed-grown examples of two very rare and challenging Central American elfin palms, greenhoused in Guatemala (2008); Chamaedorea tenerrima on the left and C. robertii on the right.

A very old example of the beautiful and rather localized Chamaedorea rigida in Oaxaca, México (Image F. Muller).

Dwarf form of Chamaedorea cf. nubium, Lempira Department, western Honduras in cultivation in California. This population is characterized by plants that mature between 4-5’/1.25-1.55 m in height, which is approximately one third the height of large C. nubium from central Guatemala and Chiapas, México. The plant shown is a particularly compact clone, mature at 11 years from seed and ~30”/75 cm in height. Other than susceptibility to spider mites, this palm is an outstanding selection for small growing areas and has shown excellent tolerance for cold temperatures overnight. Unfortunately, very few plants from this population are in cultivation and most are male.

Chamaedorea guntheriana in lightly disturbed premontane forest, Panamá Province, Panamá. Populations on this extremely localized and endangered palmlet have declined markedly over the past two decades as the result of fires and development at its sole known locality.

Established mass planting of Calyptrogyne allenii in private collection, Guatemala.

Backlit Geonoma sp. Costa Rica. (Image: F. Muller).

Chamaedorea tuerckheimii, leaf detail northeastern form from Veracruz, México. Author’s collection in California.

Geonoma monospatha, tall pinnate form, western Panamá (images: F. Muller).

Geonoma monospatha, short simple leaf form, Veraguas Province, Panamá. This diminutive morph occurs alongside typical taller, pinnate forms at localities in western Panamá, including the one shown above (Image: F. Muller).

Leaf detail, Chamaedorea amabilis, Limón Province (Image: F. Muller).

Above, several examples of the elegant cloud forest southern Central American palm, Geonoma monospatha, in Veraguas, Panamá (Images: F. Muller). A number of the smaller Middle American geonomas are polymorphic and have very striking-colored new leaves. All require cool nights and pure water to thrive.

Below, mature undisturbed lower montane rainforest habitats in northern (Caribbean versant) and southern (Pacific versant) Central America. This type of permanently cool tropical and perhumid ecosystem often harbors a diversity of dwarf species of several palm genera in close sympatry at any given locality. The future of all of the most beautiful Central American elfin palms depends on preserving large rainforest blocks at middle elevations throughout the region.

Geonoma sp. (aff. chococola?), lowland rainforest, Limón Province, Costa Rica.

Chamaedorea stricta colony, Chiapas, México. This is a highly endangered palm restricted to several cloud forest localities in extreme western Guatemala and southeastern Chiapas state (Image: F. Muller). Guatemalan plants of this species have now been propagated to F2 in California and Hawaii.