Cataract: Hot topics in ophthalmology

December 2022

by Liz Hillman

Editorial Co-Director

The use of NSAIDs in the context of cataract surgery remains a hot topic among surgeons. In 2015, the American Academy of Ophthalmology published the Topical Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Cataract Surgery OTA, which concluded that 1) “there is a lack of level 1 evidence that supports the long-term benefit of NSAID therapy to prevent vision loss from CME … ” and 2) there is no evidence that preop NSAID use “[affects] long-term visual outcomes.”1

Following this report, in 2016 the ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee published a paper in the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery calling out NSAIDs’ “history of significant safety and demonstrable effectiveness.”2

“Topical NSAIDs have been useful in preventing intraoperative miosis, postoperative inflammation, and the development of CME,” the authors wrote. “In addition, they may modulate postoperative pain and inhibit the proliferation of LECs that are responsible for PCO. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a synergistic effect with steroids on the development of CME but may be used alone in high-risk eyes in which topical steroid use may be detrimental. Whether used solely in eyes at increased risk for the development of CME or universally in all patients having cataract surgery, the benefits of these topical medications should be assessed by each clinician as appropriate for their particular practice or patient population. … A thorough understanding of the potency, approaches for avoiding and treating CME, and adverse reactions and contraindications of these medications should help surgeons maximize their benefits and improve surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

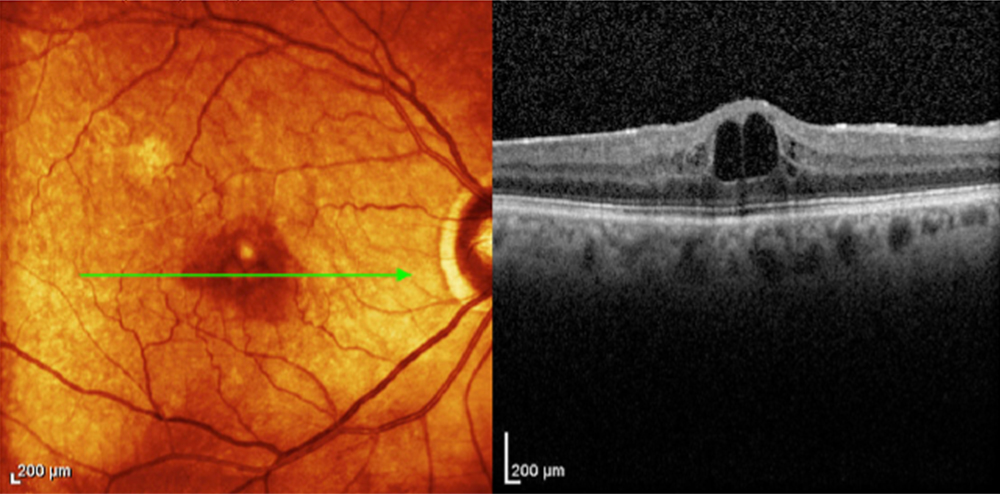

Source: Neal Shorstein, MD

EyeWorld spoke with Richard Hoffman, MD, and Neal Shorstein, MD, who were both authors on this paper, to hear their current perspectives on NSAID use in the context of cataract surgery.

Dr. Hoffman said there are “a whole host of different anti-inflammatory products for cataract surgery, including steroids and nonsteroidals.” In the latter category, he said topical NSAIDs are the mainstay, but intracameral administration is now an option with Omidria (phenylephrine and ketorolac intraocular solution, Rayner).

The biggest impediment for the use of many of these products is the expense. “Older NSAIDs, which are usually not as effective as the latest NSAID products, are less expensive for patients. I tend to stick to these older NSAIDs due to complaints from patients regarding the cost of acquiring the latest and greatest product,” Dr. Hoffman said, noting that he most frequently uses generic prednisolone acetate and generic ketorolac or bromfenac in his topical regimen. “As these newer NSAIDs become cheaper generics, I tend to switch to them.”

Dr. Shorstein said his anti-inflammatory regimen changed in 2008 when he switched from topical prednisolone to subconjunctival triamcinolone injection.

“This change occurred about 6 months after I began injecting intracameral antibiotic without topical postop antibiotic drops for endophthalmitis prophylaxis. I was comfortable injecting subconjunctival steroid, as I had experience doing this in patients with poorly controlled iritis, and there were a few studies in the literature showing the safety and effectiveness of subconjunctival steroid injections at the end of cataract surgery to reduce inflammation,” he said.

Dr. Shorstein said that when he was in practice at Kaiser Permanente (he retired from practice and is now doing research), a retrospective cohort study found reduced risk of macular edema in eyes with a combination topical drop (steroid plus NSAID) compared to steroid alone or injection of 2 mg of triamcinolone (the incidence among these latter two was similar).3

“Some surgeons surmise that the effect of reduced inflammation seen with combination treatment (steroid plus NSAID) in a number of studies comparing it to steroid alone is due to an overall increase (usually a doubling) in the total dosage of anti-inflammatory drug in the combination group,” Dr. Shorstein said. “Our group subsequently increased the dosage of triamcinolone to 4 mg, injecting a few more millimeters inferior from the limbus to reduce the risk of intraocular pressure spike, and we noticed even fewer patients with macular edema, akin to the combination group. We have not published these results as of yet.”

When asked whether NSAIDs should be used in every case or in specific, higher-risk cases, Dr. Hoffman said that he doesn’t think either stance is wrong. NSAIDS, he explained, are primarily used to reduce the incidence of postop cystoid macular edema (CME), and they offer some pain relief and can help maintain pupil dilation intraoperatively. The overall incidence of CME after cataract surgery is 1–2%, which means that 98% of patients could be using an NSAID somewhat unnecessarily, Dr. Hoffman said. Diabetic patients are more likely to develop CME, so Dr. Hoffman said he’ll order the strongest NSAIDs for these patients.

While Dr. Shorstein said his practice had been to inject steroid as the sole anti-inflammatory agent in routine patients, if patients have a history of diabetic macular edema, vein occlusion, uveitis in the operated eye, or postop macular edema in the fellow eye, he would prescribe postop diclofenac or ketorolac for 2 weeks. He also said he might add a topical NSAID to a topical steroid for younger patients (in general, he avoids injecting triamcinolone in patients younger than 50 and in high myopes) because they may exhibit a more vigorous inflammatory response.

“In my opinion, NSAIDs are a reasonable postop regimen,” Dr. Shorstein said. “The optimal treatment period, whether to begin a few days preop or not and for how long to treat after surgery (2 weeks, 4 weeks, or 6 weeks) has not been completely worked out yet. Most generic NSAIDs seem to be as effective as newer brands, however, the newer products have been approved for fewer dose instillations per day, which may increase patient adherence.”

The 2016 ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee paper stated that “Both universal and selective approaches to incorporating NSAIDs have validity, and neither should be considered a standard of care in modern cataract surgery.”

NSAIDs do carry a risk for adverse effects, namely punctate keratopathy, according to Dr. Hoffman.

“Despite this, I currently prescribe NSAIDs and steroids for all of my cataract patients, however, if they show signs of significant epitheliopathy on the first postoperative day (especially in dry eye patients), I will stop the NSAIDs but continue the topical steroids,” he said.

He added that he might hold off on NSAIDs altogether in patients with severe dry eye. On the flip side, there are patients who are steroid responders. Dr. Hoffman said these patients might have their steroid discontinued after a week but continue on a strong NSAID until the anterior chamber is quiet.

About the physicians

Richard Hoffman, MD

Drs. Fine, Hoffman, & Sims

Eugene, Oregon

Neal Shorstein, MD

Seva Foundation

Berkeley, California

References

- Kim SJ, et al. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cataract surgery: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2159–2168.

- Hoffman RS, et al. Cataract surgery and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42:1368–1379.

- Shorstein NH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of three prophylactic strategies to prevent clinical macular edema after phacoemulsification surgery. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2450–2456.

Relevant disclosures

Hoffman: None

Shorstein: None

Contact

Hoffman: rshoffman@finemd.com

Shorstein: nshorstein@seva.org