Fraternal Purpose in the Establishment of Tammany’s “American Museum”

By Timothy Winkle

On May 21, 1791, a notice appeared in New York’s Daily Advertiser, announcing the opening of what would be the first public museum in the city. It had been established “for the purpose of collecting and preserving every thing relating to the history of America, likewise, every American production of nature or art.” The “generous public” was implored to help grow the collections, an appeal not only to wealthy patrons or men of science, but, in true republican fashion, to the people themselves, for “as almost every individual possesses some article, which in itself is of little value, but in a collective view, becomes of real importance.” It would truly be an “American Museum,” of the people, by the people, and for the people. Unlike other collections of the period, this museum was uniquely created by a fraternal organization, one that most citizens of New York City knew from their parades through the streets, members dressed in supposed Indian garb. The Society of Tammany, or Columbian Order, sought to keep the spirit of patriotism alive in the hearts and minds of the city’s populace, and this museum, “although quite in its infancy,” was born of this same fraternal purpose.[1]

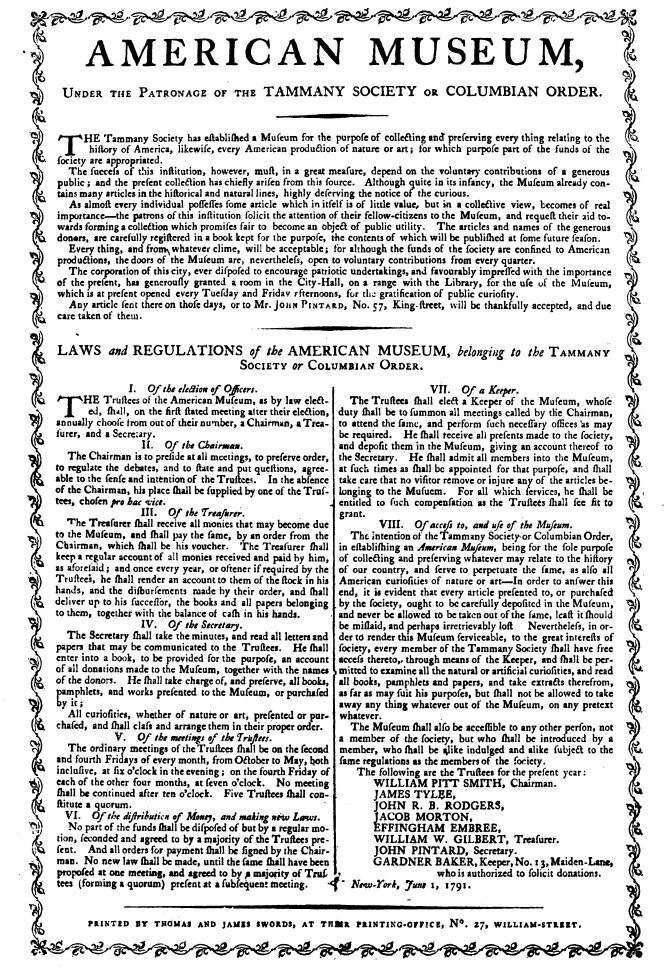

A reproduction of a broadside from June 1, 1791, repeating the announcement for the opening of Tammany’s American Museum first published in the Daily Advertiser on May 21, 1791.

The Tammany Society’s “American Museum” was not the first such venture in the early Republic. It was not even the first by that name. The Swiss émigré Pierre Eugene Du Simitiere opened his short-lived “American Museum” in Philadelphia in 1782. Charles Willson Peale occasionally advertised his 1786 venture as the “American Museum.”[2] Daniel Bowen would debut his own version – the “Columbian” – in Boston in 1791, his attempt to find a permanent venue for his famous waxworks. Despite the short or peripatetic lives of some of these early exhibitions, the creation of popularly accessible museums (that is, for those who could afford the price of a ticket or subscription) by a single enthusiastic impresario was becoming an established norm.

New York’s “American Museum” also had its own singular proponent in the person of John Pintard. A successful merchant and inveterate organizer, Pintard was the key figure in the re-establishment of the city’s Tammany Society in 1789. But Pintard was an antiquarian at heart. In correspondence, he confided in Jeremy Belknap, founder of the Massachusetts Historical Society, “my passion for American history increases” and as a means to assuage it, he claimed to have “engrafted” the idea of a museum onto the Society.[3] It was Pintard, on behalf of the Society, who petitioned the Common Council for free use of upper rooms in City Hall, prestigious if cramped quarters for a growing collection. As the museum’s secretary, Pintard solicited donations through broadsides and newspaper notices, even as he expanded his business connections in the city.

Miniature portrait of John Pintard (watercolor on ivory) from around 1785. The image is attached to a wristlet worn by his wife. Courtesy of New-York Historical Society

Though put in motion by John Pintard’s vision, the museum was a Tammany Society enterprise. In comparison to other contemporary exhibitions of the time, their museum seems more in line with later professional institutions – a (initially) free institution established by a public-minded non-profit group, with board of trustees, paid staff, registration procedures, even a loan policy - that is, nothing was to be removed from the museum for any reason, not even by members of the Society. It even had a mission statement and collections policy. As the May 21st notice in the Daily Advertiser indicated, while the museum was established to collect and preserve the products of America, the museum’s trustees would accept any donation – “every thing, and from whatever clime, will be acceptable for although the funds of the society are confined to American productions, the doors of the Museum are, nevertheless, open to voluntary contributions from every quarter.”[4]

Detail from a late-19th century lithograph depicting Federal Hall in 1789. Upon the removal of the national capital to Philadelphia, the city government returned to the building and made upper rooms available to the Tammany Society for use as their museum. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The museum’s sponsorship by a fraternal organization, one with elaborate costumes and solemn obligations to keep its secrets, is perhaps the most incongruous aspect for such a venture. Though museums of the period were not the exclusive domain of individual promoters, organizational collections were normally not open to the general public. Medical schools, such as the Pennsylvania Hospital, maintained anatomical collections. The Charleston Museum was established in 1773 by the library company of that city, exclusive to its members until the 1820s. The creation of a public museum by a private association, and a fraternal one at that, was unique at the time. Others would follow - the East India Marine Society’s Salem museum in 1799, for instance. In establishing the museum, the Tammany Society appeared to be testing the limits of what was acceptable and respectable participation within the public sphere by a type of organization normally marked by private fellowship and introspection. What spurred these men to move beyond parading and patriotic toasts, beyond affecting Native American names and ritual, into such a direct relationship with their fellow citizens?

Part of the answer can be found in the principles underlying the establishment of the fraternity itself. In the New-York Register for 1791, in which the new museum was also advertised, the entry for “Tammany’s Society, or Columbian Order” declared the “national institution” had three objects – “the smiles of charity, the chain of friendship, and the flame of liberty.”[5] The pursuit of knowledge was a foundational principle for the American fraternal experience. Beginning in Great Britain in the 17th century, Freemasonry had taken root in the colonies in the late 1720s, and by the latter part of the century, it served as the template for the establishment of new, homegrown fraternal groups, such as Tammany. As Stephen Bullock has noted in Revolutionary Brotherhood, his account of early American Freemasonry, while their European brethren often focused on the supposed hermetic and mystical origins of their “craft,” American Masons tended to focus on an ancient legacy of learning and scientific knowledge.

The quest for knowledge, the pursuit of individual mental improvement through the study of the arts and sciences was fundamental to the experience of American Freemasonry and American republicanism. In December 1793, DeWitt Clinton, a Freemason and Tammany “brave,” encapsulated this view in an address to the Masonic brethren of New York City’s Holland Lodge, charging them that “every Mason ought to enrich his mind with knowledge, not only because it better qualifies him to discharge the duties of the character, but because information and virtue are generally to be found in the same society.”

The patriotic promotion of liberty, on the other hand, was an inherently public pursuit. Unlike contemporary New York fraternal groups such as the Freemasons and the Black Friars, whose membership focused on sociability and self-improvement, those who would re-establish Tammany Society saw its purpose as explicitly public-minded and political. Many Tammany officials were also members of the Holland Lodge, including Pintard, Mooney and William Pitt Smith (Tammany’s second “Grand Sachem”). The group’s relaunch in 1789 was set against the background of Federalist control in New York City, with merchants and mechanics temporarily united politically and patriotic nationalism permeating the public sentiment. According to their constitution, the group would “connect in the indissoluble bonds of patriotic friendship American brethren of known attachment to the political rights of human nature and the liberties of their Country.” This did not include Loyalists, recently returned to the city, nor foreigners, especially Catholics (non-Americans could join but were relegated to ceremonial roles such as “hunter”). According to a 1789 address by William Mooney, upholsterer and the group’s first “Grand Sachem,” the Tammany Society was created to protect American rights and “to counteract the machinations of those Slaves and Agents of foreign Despots.” Groups based on foreign national origin, such as the English St. George Society, were viewed with deep suspicion, if not outright hostility. Conversely, as a corollary to America’s own struggles and ideals, support for the French Revolution was deeply entrenched (Baker would even display a working guillotine and headless wax figure at the museum).[6]

This nationalistic agenda was public-facing and intended to be instructive. Much of the activities of the Tammany Society in its first five years of its existence were intended to showcase American identity and values, to fellow citizens and visitors alike. In 1790, with the capital still located in the city, the Tammany Society injected themselves into government affairs, taking it upon themselves to officially greet and host Oneida and Creek delegations, acting as an honor guard to escort them through the streets of the city to meet with members of the federal administration. The group offered a somewhat relentless program of public activities – parades throughout the year, toasts and lectures (or “long talks”), stage performances, even public works (in 1794, Tammany members volunteered to build up the city defenses at Governor’s Island[7]). The Society took on quasi-bank status in launching a public tontine in early 1792, ostensibly to fund a permanent hall and home for the museum. Tammany “braves” publicly paraded in their own version of Indian costume, marking their anniversary (May 12) as well as secular holidays of patriotic importance – Independence Day and Evacuation Day, for instance. They were among the first to publicly celebrate George Washington’s birthday in 1790, and pioneered the national commemoration of Columbus Day, marking the 1792 tricentennial with parades, toasts, and the unveiling of a 14-foot obelisk, made to resemble black marble, dedicated to Columbus as both discoverer of America and victim of monarchy. This “portable monument” was later installed as a feature in the museum.

Detail from an illustration of a Tammany Society medal, possibly an officer’s jewel, from Wayte Raymond’s catalogue of the numismatic collections of W. W. C. Wilson (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1925). Columbus and Tammany, joint patrons of the Society, clasp hands in friendship, below the motto “Where Liberty Dwells, there is my Country.”

Tammany’s “American Museum” was a key part of this didactic and public expression of identity. As already mentioned, the by-laws that had established the museum specifically limited purchases for display to “American productions.” Despite the wide array of items on view, accounts often emphasized the abundance of Indian objects on display, and, indeed, a 1793 broadsheet lists native bows and arrows, weapons, clothing and decoration in the collection.[8] One of the first donations to the museum was a copy of John Eliot’s so-called “Indian Bible” of 1663. As with the adoption of the legendary Tammany as their patron, the prominent inclusion of Native American artifacts for public display not only matched the fraternal trappings of the Society but can also be seen as an attempt to highlight an antiquarian legacy on par with that of Europe, creating a “usable past” that fit the group’s preferred themes for the young republic. Citizens could see unique American fauna, from stuffed bison and alligators to a live bald eagle and a grey squirrel that operated a pepper grinder. American ingenuity and manufacture were combined in the display of an “air gun” that could discharge 20 shots at a time (for a small charge, visitors could even fire it).

Visitors to the museum could even encounter American history in the flesh. Late in December of 1794, James French, a survivor of the army under General St. Clair at the Battle of the Wabash, was put on display after his arrival in the city. According to the public advertisement, those attending could inquire about his experiences and examine “the wound of the Tomahawk in his head, and the place where the scalp was taken from.”[9] The display of James French would also meet another of Tammany’s fraternal purposes – “the smiles of charity.” The organization was certainly philanthropic, active in supporting New York City causes, such as the Dispensary and charity schools. In this case, James French stopped in the city on his way to Philadelphia, where he hoped to secure a pension for his military service. Those who came to view him at the museum were encouraged to donate to a fund intended to by him new clothes and further his journey to the capital.[10]

Tammany’s creation of a public museum was in line with its publicly stated purposes of brotherhood, charity, and (especially) patriotism, albeit threaded with nationalist sentiment. In establishment of their American Museum, however, another fraternal purpose may well have been at work – that of education and public edification.

In his address to the Society on their May 12th anniversary in 1790, Dr. William Pitt Smith, member of the Columbia College faculty and Tammany’s second “Grand Sachem,” framed the group’s existence around the tenets of “patriotism, philosophy, and benevolence,” and that philosophical purpose revolved around the “pursuit of science and truth.” In Smith’s view, human nature is improved and refined by the rational application of “celestial science,” while the darker aspects of civilization shrank away. The very future of the American experiment would be determined by the education of its participants: ‘It is indeed questionable, whether an ignorant people can be happy, or even exist, under what Americans call free government. It may also be doubted, whether a truly enlightened people were ever enslaved. Science is so meliorating in its influence upon the human mind, that even he who holds the reins of power, and hath felt its rays, loses the desire of a tyrant, and is best gratified in the sense of public love and admiration.”

Tammany’s American Museum was still a year from its debut, but Pintard and Smith (who would also serve in its first group of trustees) were no doubt immersed in its creation. Near the close of his talk, Pitt tells his fellow Tammany members that under the framework of republican enlightenment, “your American museum presents itself as worthy the most zealous encouragement.”[11]

In the upper floor of City Hall in 1791, the American Museum of New York’s Tammany Society fused fraternal and national imperatives. The information imparted by its displays and the knowledge that was physically embodied in its artifacts served to satisfy the educational edicts of American Freemasonry and its progeny (including Tammany) as well as the republican needs for an informed and enlightened populace. As the Society observed in their opening notice, the collection was intended to become an “object of public utility,” one that would help to educate the citizens of the city and of the nation as a whole, not only with the knowledge of their history and the world around them, but also in their own national identity, and what it was to be American. Though Pintard was brought low by the financial panic of 1792—he fled his creditors by relocating to Newark and would spend several months in debtor’s prison—the American Museum continued under Gardiner Baker, Pintard’s museum manager and science-minded promoter.[12] The Tammany Society would gift the museum to Baker in 1795, and upon his death shortly thereafter, the collections passed through several hands until becoming part of another of “American Museum,” this time under the management of P. T. Barnum.

Timothy Winkle is a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, where he is responsible for fraternal history and community organizations. He received an MA in Popular Culture Studies from Bowling Green State University and an MA in Museum Studies from University College of London.

[1] New York Daily Advertiser, May 21, 1791 as referenced in Stokes, I. N. Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 New York : Robert H. Dodd, 1915-1928.Electronic reproduction. p. 1280, v. 5. New York, N.Y. : Columbia University Libraries, 2008. JPEG use copy available via the World Wide Web. Master copy stored locally on [74] DVDs#: ldpd_5800727_001 01-13 ; ldpd_5800727_002 01-19 ; ldpd_5800727_003 01-16 ; ldpd_5800727_004 01-16.. Columbia University Libraries Electronic Books. 2006.

[2] “Lately presented to Mr. Peale’s American Museum” The Pennsylvania Packet, May 21, 1789, p. 3 (donations included several from Samuel Latham Mitchill, scientist and member of Tammany).

[3] As noted in Kilroe, Edwin P. Saint Tammany and the Origin of the Society of the Tammany: Or Columbian Order in the City of New York (New York: M. B. Browning, 1913), p.136, p.155n.

[4] New York Daily Advertiser, May 21, 1791 as referenced in Stokes, I. N. Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 New York : Robert H. Dodd, 1915-1928.Electronic reproduction. p. 1280, v. 5. New York, N.Y. : Columbia University Libraries, 2008. JPEG use copy available via the World Wide Web. Master copy stored locally on [74] DVDs#: ldpd_5800727_001 01-13 ; ldpd_5800727_002 01-19 ; ldpd_5800727_003 01-16 ; ldpd_5800727_004 01-16.. Columbia University Libraries Electronic Books. 2006.

[5] Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. "New York City directory" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1791. p. 48. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c17c01a0-ea58-0134-e644-063df2ab41c5

[6] Tammany constitution and William Mooney’s address in Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Constitution and roll of members" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1916. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/de6fb340-b31c-0133-f5b0-00505686d14e

[7] Dennis, Matthew. “The Eighteenth-Century Discovery of Columbus” in Pencak, William and Dennis, Matthew, eds. Riot and Revelry in Early America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010.

[8] Francis, John Wakefield. Old New York: Or, Reminiscences of the Past Sixty Years. New York: W. J. Widdleton, 1866. p. 124.

[9] As referenced in Ellen Fernandez-Sacco (2002), “Framing ‘The Indian’: The Visual Culture of Conquest in the Museums of Pierre Eugene Du Simitiere and Charles Willson Peale, 1779–96,” Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, 8:4, 571–618, DOI: 10.1080/1350463022000068389

[10] The pairing of fraternal charity and museum exhibition was even more evident in the establishment of the Alexandria Museum, formed by the masonic Alexandria Washington Lodge No. 22 in 1812, in what was then the District of Columbia. According to its circular, still in the lodge’s collections, any profits from entry fees were meant “to raise a perpetual Charity Fund for the relief of the Poor and Helpless who may pass this way, or dwell amongst us.”

[11] “An Oration, delivered by Dr. William Pitt Smith, before the Society of St. Tammany…” The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository. May 1790; 1, 5; American Periodicals, p. 290.

[12] Upon his return to the city, John Pintard would have another opportunity at the preservation of history, this time as the founder of the New-York Historical Society in 1804.