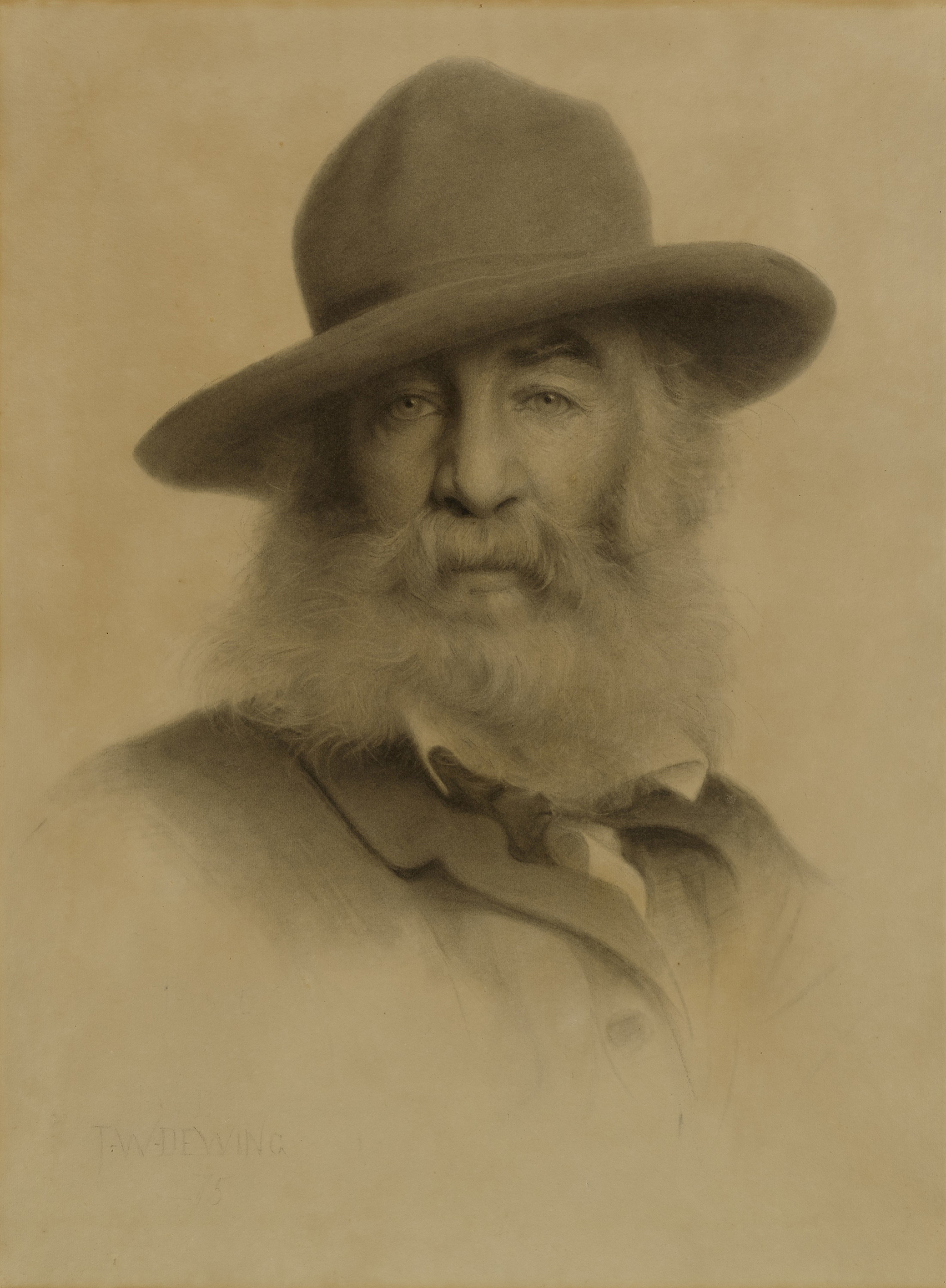

Walt Whitman, by Thomas Wilmer Dewing, 1875. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Robert Tyler Davis Memorial Fund.

At the beginning of Specimen Days, a collection of sketches and notes published in 1882 that amounts to a sort of autobiography of Walt Whitman, the poet shares the story of how he became a reader. He was working his first job as an errand boy in a lawyers’ office where he had a window nook all to himself. One of his bosses signed him up for a circulating library. It was a seminal moment.

For a time I now revel’d in romance-reading of all kinds; first, the Arabian Nights, all the volumes, an amazing treat. Then, with sorties in very many other directions, took in Walter Scott’s novels, one after another, and his poetry (and continue to enjoy novels and poetry to this day).

Whitman was omnivorous; “[I] devour’d everything I could get,” he said. Below is a sampling of what was on the menu.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“If anybody cares to know what I think—and have long thought and avow’d—about them,” Whitman writes in Specimen Days, “I am entirely willing to propound. I can’t imagine any better luck befalling these States for a poetical beginning and initiation than has come from Emerson, Longfellow, Bryant, and Whittier. Emerson, to me, stands unmistakably at the head, but for the others I am at a loss where to give any precedence.”

Whitman had the chance to visit the transcendentalist in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1881, and then visited Emerson’s fresh grave seven months later, paying tribute to a “just man, poised on himself, all-loving, all-enclosing, and sane and clear as the sun.” (Sixteen years his junior, Whitman outlived him by a decade.) The disciple was perhaps predisposed to like the man. Emerson had written Whitman a letter in 1855 after reading Leaves of Grass—which had been inspired in part by Emerson’s “The Poet”—calling it “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy.”

I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It has the best merits, namely, of fortifying and encouraging.

Whitman had his printers put Emerson’s letter—especially the line “I greet you at the beginning of a great career”—on later editions of Leaves of Grass, and gave the New York Tribune a copy so it could print the praise without asking for permission from its author. Emerson wrote to his friend Samuel Longfellow that Whitman had “done a strange rude thing” by having the letter bandied about.

In a reflection on the man that Whitman later put in Specimen Days, Whitman confessed that his adulation of the man was perhaps partly a case of a youngster hungry to attach himself to a hero. He had “Emerson-on-the-brain—that I read his writings reverently, and address’d him in print as ‘Master,’ and for a month or so thought of him as such…I have noticed that most young people of eager minds pass through this stage of exercise.”

The best part of Emersonianism is, it breeds the giant that destroys itself. Who wants to be any man’s mere follower? lurks behind every page. No teacher ever taught, that has so provided for his pupil’s setting up independently—no truer evolutionist.

Emerson’s influence, according to Whitman, “is to make his students cease to worship anything—almost cease to believe in anything outside themselves. These books will fill, and well fill, certain stretches of life, certain stages of development—are (like the tenets or theology the author of them preach’d when a young man) unspeakably serviceable and precious as a stage. But in old or nervous or solemnest or dying hours, when one needs the impalpably soothing and vitalyzing influences of abysmic Nature, or its affinities in literature or human society, and the soul resents the keenest mere intellection, they will not be sought for.”

His pages, Whitman goes on, “are perhaps too perfect, too concentrated. (How good, for instance, is good butter, good sugar. But to be eating nothing but sugar and butter all the time! Even if ever so good.)”

Whitman also enjoyed reading and learning about Henry David Thoreau. He wrote a letter to one of Thoreau’s biographers, journalist Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, to say he was indebted to Sanborn for the book, which approached biography from an angle that Whitman liked.

The telling of life after all refuses to be put in a polish’d, formal, consecutive statement—better, living glints, samples, autographic letters above all, memoranda of friends &c—You have pursued this plan & the result justifies—Froude’s late Carlyle, a precious book, pursues it too—& succeeds—

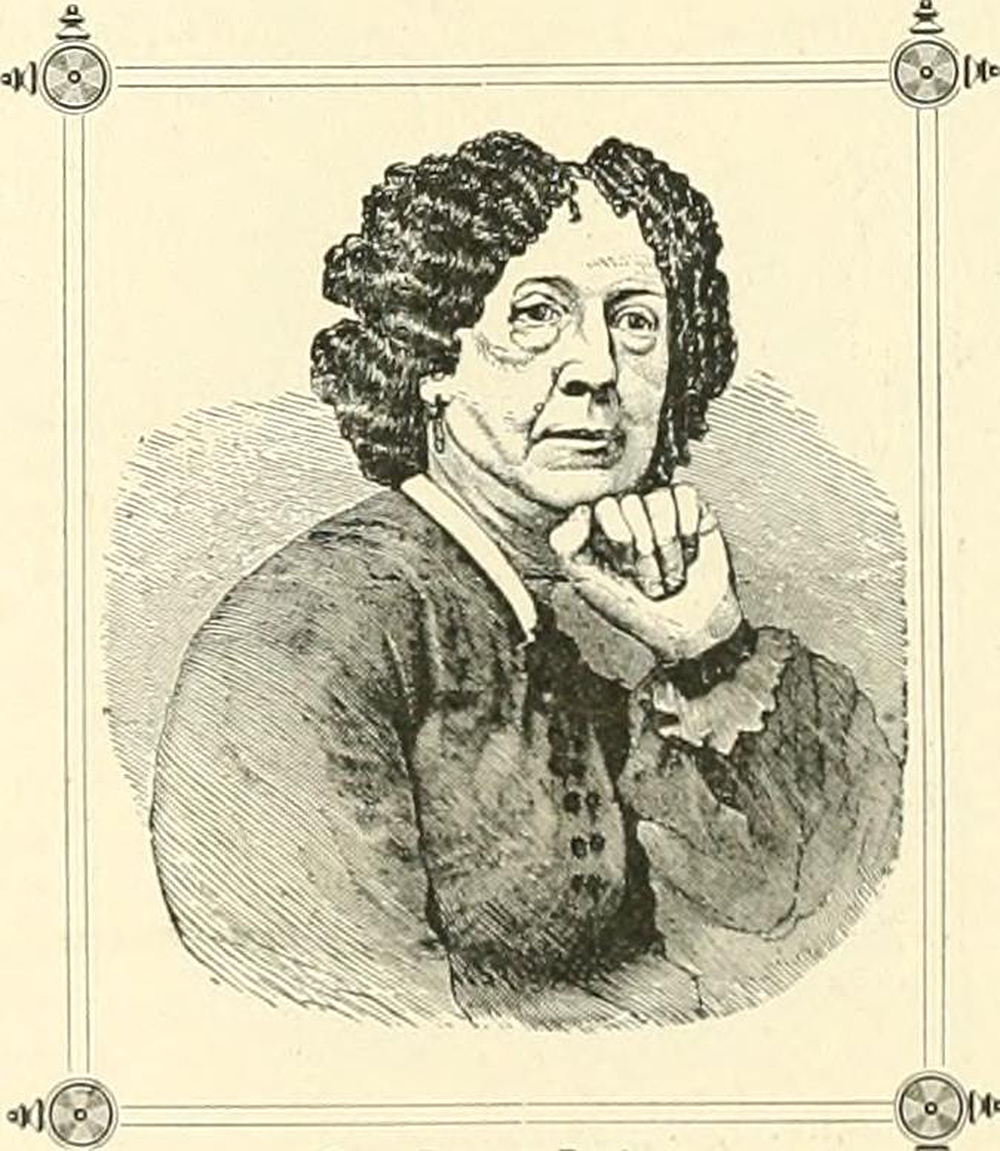

Fanny Fern

“Leaves of Grass”

You are delicious! may my right hand wither if I don’t tell the world before another week, what one woman thinks of you.

The famous newspaper humorist Sarah Payson Willis, better known by her pen name Fanny Fern, was also one of the few people to champion Leaves of Grass when it first appeared—and the first woman to praise it in print. She wrote the above note to Whitman in 1856, and he kept it—although he didn’t rush to have it printed in the papers. He also didn’t need to; Fern’s column about his poems appeared in the New York Ledger a few weeks later.

Walt Whitman, the effeminate world needed thee…Where an Emerson, and a Howitt have commended, my woman’s voice of praise may not avail; but happiness was born a twin, and so I would fain share with others the unmingled delight which these “Leaves” have given me.

I say unmingled; I am not unaware that the charge of coarseness and sensuality has been affixed to them. My moral constitution may be hopelessly tainted or—too sound to be tainted, as the critic wills, but I confess that I extract no poison from these Leaves—to me they have brought only healing.

Fern was much more famous than Whitman at the time; her columns were widely read, her books bestsellers. They met and briefly were friends—camaraderie that may have withered when Whitman failed to pay back a loan from Fern and her husband.

From what Whitman told publisher and writer Horace Traubel in a letter, it seems he thought that his book of poetry was designed to appeal to female literary connoisseurs:

Leaves of Grass is essentially a woman’s book: the women do not know it, but every now and then a woman shows that she knows it: it speaks out the necessities, its cry is the cry of the right and wrong of the woman sex—of the woman first of all, of the facts of creation first of all—of the feminine: speaks out loud: warns, encourages, persuades, points the way.

William Shakespeare

Whitman loved New York City, the place where he set many poems and worked as a journalist. One specific location that sparked joy: the bus that traveled down Broadway.

As he wrote in Specimen Days,

How many hours, forenoons and afternoons—how many exhilarating nighttimes I have had—perhaps June or July, in cooler air—riding the whole length of Broadway, listening to some yarn (and the most vivid yarns ever spun, and the rarest mimicry)—or perhaps I declaiming some stormy passage from Julius Caesar or Richard (you could roar as loudly as you chose in that heavy, dense, uninterrupted street-bass.)

He repeated such behavior when traveling across the East River on the ferry, but Shakespeare wasn’t reserved for public transportation. Whitman was also known to head to Coney Island and “and declaim Homer or Shakespeare to the surf and seagulls by the hour.”

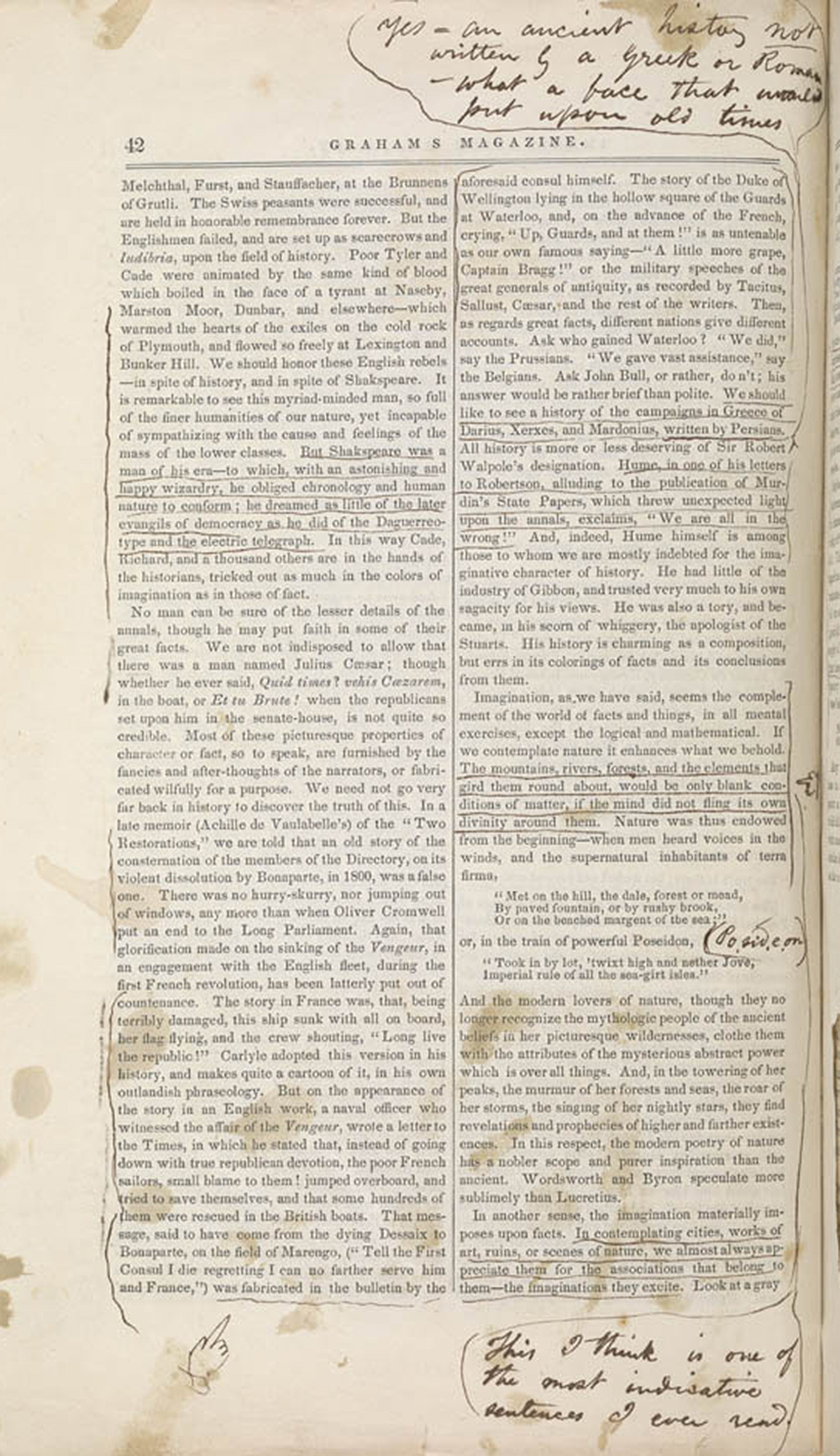

“Imagination and Fact”

Imagination, as we have said, seems the complement of the world of facts and things, in all mental exercises, except the logical and mathematical. If we contemplate nature it enhances what we behold. The mountains, rivers, forests, and the elements that gird them round about, would be only blank conditions of matter, if the mind did not fling its own divinity around them.

Walt Whitman underlined these words in his January 1852 copy of Graham’s Illustrated Magazine of Literature, Romance, Art, and Fashion, which reprinted an essay titled “Imagination and Fact” that had originally been published in the November 1851 issue of the American Whig Review. The line that began “The mountains, rivers, forests,” Whitman wrote in a cloud emanating from a tiny manicule inscribed on the page, “was one of the most indicative sentences I ever read.” In another bubble next to the line “We should like to see a history of the campaigns in Greece of Darius, Xerxes, and Mardonius, written by Persians,” he wrote, “Yes—an ancient history not written by a Greek or Roman—what a face that would put upon old times.”

The author of this essay remains anonymous, but Graham’s Illustrated Magazine of Literature, Romance, Art, and Fashion did publish many other writers that Whitman read or knew of: Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and James Fenimore Cooper, who was the magazine’s highest paid writer.

Edgar Allan Poe

“For a long while, and until lately, I had a distaste for Poe’s writings,” Whitman said in a November 1875 newspaper interview concerning a new monument to the poet erected in Baltimore.

I wanted, and still want for poetry, the clear sun shining, and fresh air blowing—the strength and power of health, not of delirium, even amid the stormiest passions—with always the background of the eternal moralities. Non-complying with these requirements, Poe’s genius has yet conquer’d a special recognition for itself, and I too have come to fully admit it, and appreciate it and him.

He once had a dream about a boat stuck out at sea during a midnight storm.

It was no great full-rigg’d ship, nor majestic steamer, steering firmly through the gale, but seem’d one of those superb little schooner yachts I had often seen lying anchor’d, rocking so jauntily, in the waters around New York, or up Long Island sound—now flying uncontroll’d with torn sails and broken spars through the wild sleet and winds and waves of the night. On the deck was a slender, slight, beautiful figure, a dim man, apparently enjoying all the terror, the murk, and the dislocation of which he was the centre and the victim. That figure of my lurid dream might stand for Edgar Poe, his spirit, his fortunes, and his poems—themselves all lurid dreams.

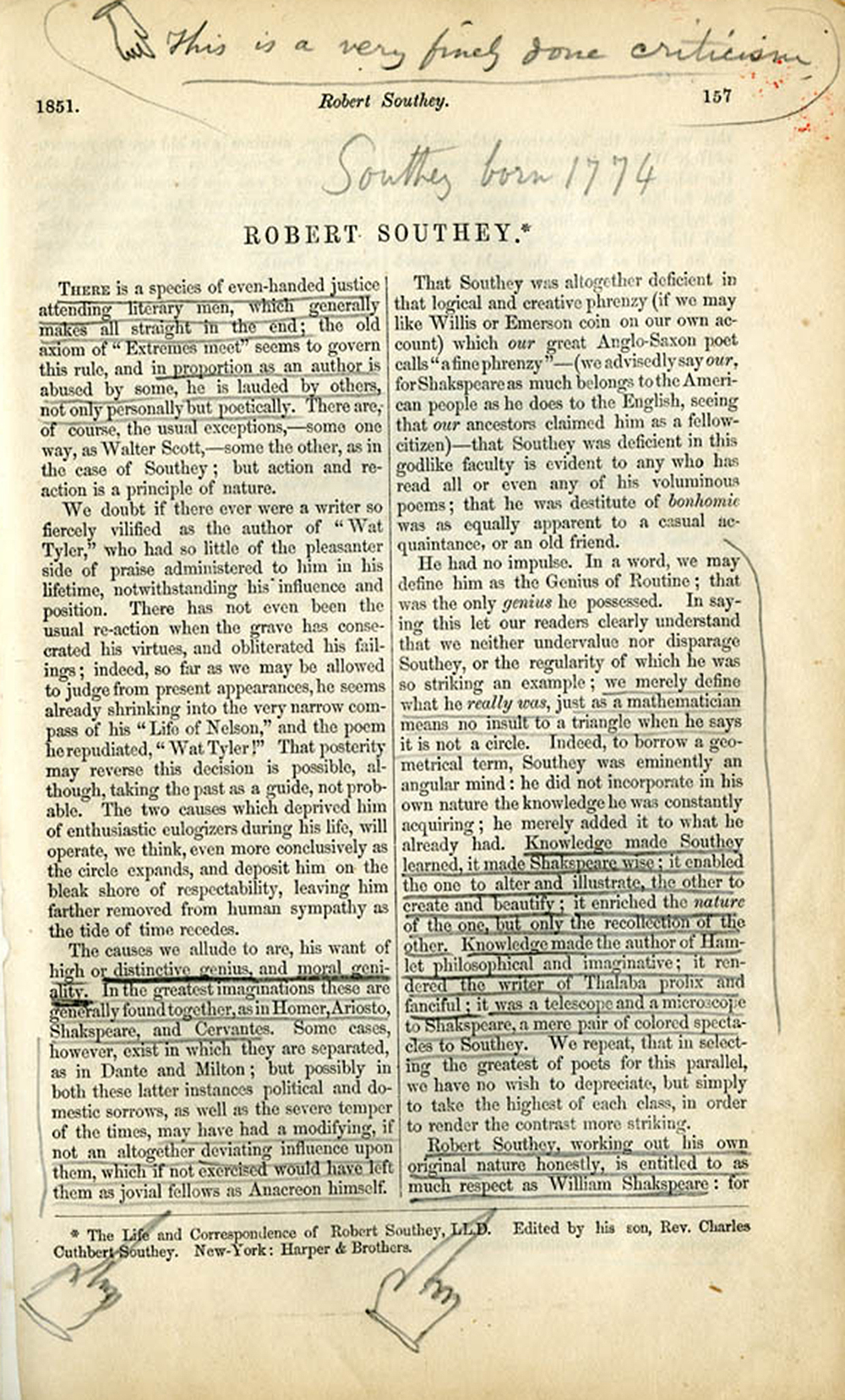

Robert Southey

In another issue of the American Whig Review, Whitman thoroughly marked up an article about Robert Southey. His penciled manicules aggressively pointed at lines he thought particularly good. “This,” he wrote at the top with one of his insistent pointing hands, “is a very finely done criticism.” He especially liked the line “Robert Southey, working out his own original nature honestly, is entitled to as much respect as William Shakespeare.”

Yet in a July 1846 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the newspaper he edited for many years, he wrote that “Walter Scott, Croly, Alison, Southey, and many others well known in America exercise an evil influence through their books, in more than one respect; for they laugh to scorn the idea of republican freedom and virtue.”

Kenelm Chillingly

On June 23, 1873, Whitman wrote a letter to Charles W. Eldridge from his home in Camden, New Jersey—the place, as he notes in the letter, where his mother died. He’s sleeping well, eating, but he is getting old. “My head does not get right,” he writes, “that being still the trouble—the feeling now being as if it were in the center of the head, heavy & painful & quite pervading—locomotion about the same—no better. I keep pretty good spirits, however, & still make my calculations on getting well.” But his head is well enough for him to read a book.

I have amused myself with Kenelm Chillingly—read it all—like it well—Bulwer is such a snob as almost redeems snobdom—the story is good, & the style a master’s—Like Cervantes, Bulwer’s old-age-productions are incomparably his best.

Kenelm Chillingly was published in 1873, the year its author, Edward Bulwer Lytton, died. Although few remember Lord Lytton or his last novel, several of his ideas outlived him, if rarely packaged with his name. He came up with the phrases “The pen is mightier than the sword,” “pursuit of the almighty dollar,” and “the great unwashed.” He was not the first writer to start a novel with the line “It was a dark and stormy night,” although he was the person to make the line famous for being terrible, in his 1830 novel Paul Clifford.

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Lytton also wrote The Coming Race, a science fiction novel influential with theosophists (and maybe Nazis) about a subterranean master race that considers women superior to men.

The New York Times review of Kenelm Chillingly sums up the book as a beautiful, if messy, posthumous offering.

While the character of Chillingly is clearly drawn, and is certainly a genuine creation of its author, there is much that is fault in the conception of it. The brilliancy of his epigrams is scarcely true to nature, and at times the young man impresses the reader as a rather tiresome and quite impossible person. He is, however, the most successful creation to be found in the long list of Lord Lytton’s heroes, and he is certainly new to English fiction. In the women to whom the reader is introduced there is the usual Lytto-man absence of flesh and blood, and though they are less exasperating than the lifeless fashion plates that adorn the author’s earlier novels, it is impossible to accept them as actual or desirable women. The plot of the book is meager, but there is no lack of incident or interest in its pages.

Alfred Tennyson

“Yes, Alfred Tennyson’s is a superb character, and will help give illustriousness, through the long roll of time, to our nineteenth century,” Whitman wrote in Specimen Days.

In its bunch of orbic names, shining like a constellation of stars, his will be one of the brightest. His very faults, doubts, swervings, doublings upon himself, have been typical of our age. We are like the voyagers of a ship, casting off for new seas, distant shores. We would still dwell in the old suffocating and dead haunts, remembering and magnifying their pleasant experiences only, and more than once impell’d to jump ashore before it is too late, and stay where our fathers stay’d, and live as they lived.

Maybe I am non-literary and non-decorous (let me at least be human, and pay part of my debt) in this word about Tennyson. I want him to realize that here is a great and ardent Nation that absorbs his songs, and has a respect and affection for him personally, as almost for no other foreigner. I want this word to go to the old man at Farringford as conveying no more than the simple truth; and that truth (a little Christmas gift) no slight one either. I have written impromptu, and shall let it all go at that.

He said in conclusion, “Best thanks, anyhow, to Alfred Tennyson—thanks and appreciation in America’s name.”

Robert Williams Buchanan

“I have read this little sketch three or four times—at intervals—sometimes when ‘gloomy’—& every time it sets me up,” Whitman wrote at the top of Robert Williams Buchanan’s story “The Fair Pilot of Loch Uribol: A Yachting Episode,” published in The Saint Paul’s Magazine in 1872. Whitman also left some marginalia at the end of the tale: “one of my favorite stories.”

The British writer Buchanan—described as a “poet, novelist, playwright, and controversialist” in his New York Times obituary—is not much remembered anymore, and when he is remembered it is more for denouncing the pre-Raphaelites as “the Fleshly School of Poetry” rather than for any sentences he managed to string together into a longer work. Algernon Charles Swinburne later jumped to defend Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his crowd in a long attack against Buchanan published in his Under the Microscope.

I cannot profess to have read any book of Mr. Buchanan’s; for aught I know, they may deserve all his praises; it is neither my business nor my desire to decide. But sundry of his contributions in verse and prose to various magazines and newspapers I have looked through or glanced over—not, I trust, without profit; not, I know, without amusement.

The eviscerating goes on.

Time may have hidden from the eye of biography the facts of Shakespeare’s life, as time has revealed to the eye of criticism the grossness of his works and the purity of his rival’s; but none need fear that the next age will have to lament the absence of materials for a life of Buchanan. Not once or twice has he told in simple prose of his sorrows and aspirations, his struggles and his aims. He has told us what good man gave him in his need a cup of cold water, and what bad man accused him of sycophancy in the expression of his thanks. He has told us what advantage was taken of his tender age by heartless publishers, what construction was put upon his gushing gratitude by heartless reviewers. He has told us that he never can forget his first friends; he has shown us that he never can forget himself.

But he had at least one fan who read his story about a boat whenever he felt blue.

The Bible

“This afternoon, July 22d, I have spent a long time with Oscar F. Wilber, company G, 154th New York, low with chronic diarrhoea, and a bad wound also,” Whitman wrote in a sketch in Specimen Days, documenting a moment from his time serving as a nurse in the Civil War.

He asked me to read him a chapter in the New Testament. I complied, and ask’d him what I should read. He said, “Make your own choice.” I open’d at the close of one of the first books of the evangelists, and read the chapters describing the latter hours of Christ, and the scenes at the crucifixion. The poor, wasted young man ask’d me to read the following chapter also, how Christ rose again. I read very slowly, for Oscar was feeble. It pleased him very much, yet the tears were in his eyes. He ask’d me if I enjoy’d religion. I said, “Perhaps not, my dear, in the way you mean, and yet, maybe, it is the same thing.” He said, “It is my chief reliance.” He talk’d of death, and said he did not fear it. I said, “Why, Oscar, don’t you think you will get well?” He said, “I may, but it is not probable.” He spoke calmly of his condition. The wound was very bad, it discharg’d much. Then the diarrhoea had prostrated him, and I felt that he was even then the same as dying. He behaved very manly and affectionate. The kiss I gave him as I was about leaving he return’d fourfold. He gave me his mother’s address, Mrs. Sally D. Wilber, Alleghany post office, Cattaraugus County, New York. I had several such interviews with him. He died a few days after the one just described.

For other menus prepared by other famous word devourers, see past entries in our reading list series: Julia Ward Howe, Walt Whitman, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Frederick Douglass, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roosevelt, Nella Larsen, Flannery O’Connor, and Emily Dickinson.