The Insidious Creep Of Inefficiency

A sub-edited version of this article was published by Gulf News dd. April 11, 2019, headed "Take a better grip of grappling with costs creeping up" (link).

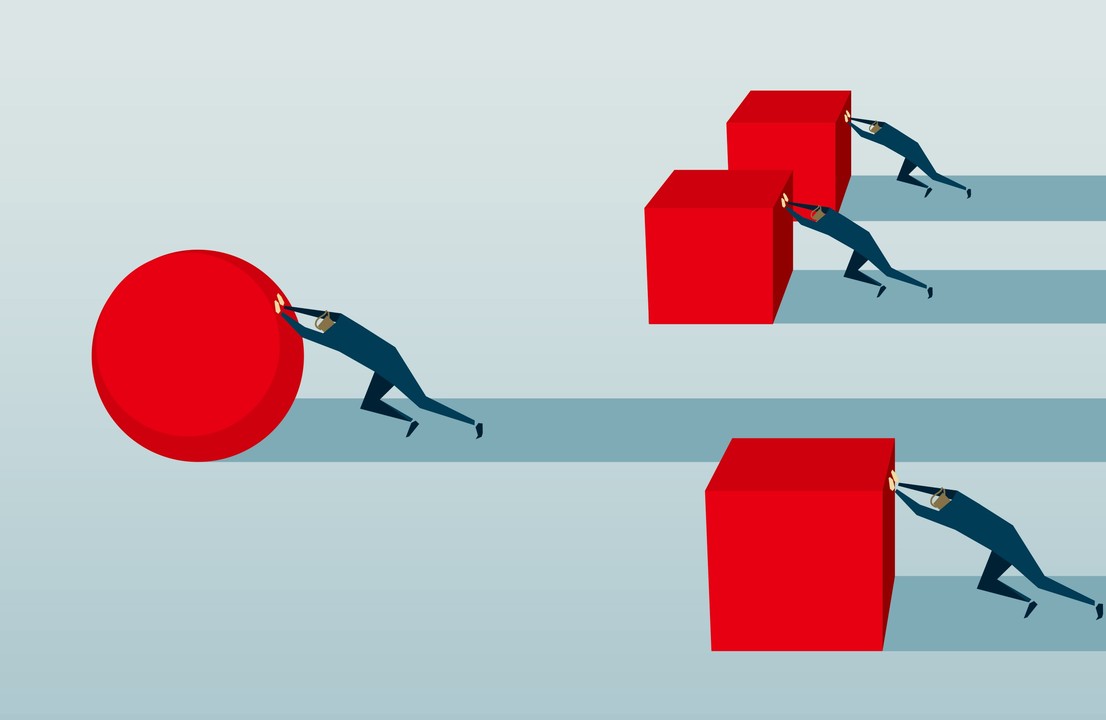

Over the years, I have noticed that organisations appear to have a natural tendency towards inefficiency and entropy.

Every year, budgets creep by 5% here and 10% there. Yes, it is a fact that we will spend more on utilities next year, and yes, we desperately need another salesman and more manpower in production to handle the workload. It is only one more person and it is only a small increase in overheads, but it is necessary. This division is one of our largest and most profitable, so it is worth the investment.

Any of these reasons when taken in isolation is completely reasonable, even logical, and therefore very hard to dispute. In many organisations that is even how budgets are set. We take last year’s full year figures, add a few percent for inflation and cost increases, apply the same logical growth to revenue to cover the increased overheads, which is an easy “fix”, and there we go, the annual budget is done.

The problem with this approach is that it is not based on reality. It is the start of a very slippery slope whereby the compound effect of all these cost increases and small reductions in efficiency quickly add up. In two or three years, what was once a very profitable and efficient business, or product or service line, suddenly starts to look less shiny. When a competitor comes along who can do what we do for less than our cost, we say it is ridiculous, it is surely not possible, we have been doing this for years, so we know how much it costs to make, they must be losing money.

The brutal fact is that we have grown fat, and this leaves us exposed to lean and hungry upstarts with low overheads who have not been piling on costs year after year. We have eroded our own margins and tied up capital and investments in less efficient parts of the business, which prevents us from reacting and investing in the areas of the biggest growth. Despite always being busy, we never seem to have free resources to allocate into new exciting areas of potential growth, so we do nothing, we entropy.

To compound this, our steady growth projections in revenue that assume we will grow by that same 5% per year for established divisions, or more worryingly, the magical hockey stick of exponential growth that we all aspire to often fail to materialise, resulting in the “hairy-back” we see with so many autopsies of failed sales forecasts.

I came to the conclusion that our company was also suffering from this exact symptom some time ago when watching a video of a task being performed that required seven people to complete. Now, many of our works are quite labour intensive, so this is not necessarily a surprise. However, at the same time I noticed our historical timing estimates were based on three people, not seven. On inspecting footage from three years earlier, there were indeed only three people doing exactly the same task. This must mean that over the past three years, at least for this task, and in likelihood many more across the organisation, we now need 60% more resources to do exactly the same task. If the same logic is applied across the board, then every year that we have added additional resources with the view to improve productivity. Those resources have in fact just been absorbed into the organisation and not generated the additional productivity they were intended to. I do not think this happened quickly, nor intentionally. It was a gradual process, so gradual that we did not even notice.

We are not working less hours, in fact everyone is working harder and longer than ever before. How did this happen - Was it a conscious decision? Laziness? Ineptitude? I do not think it is any of these. I think it is the gradual tendency of any organisation, and those within it, to hit autopilot, to ease off the accelerator and without conscious thought it becomes the natural pace. This is why we can achieve more some days in 2 hours than we can in 10 hours – because our default is to self-pace ourselves to fit our work day into the available time. We also have natural scope creep, which is an equally insidious fact of life. Over time, we take on more and more tasks but rarely drop tasks. We add more processes, checklists, quality controls but never think to stop, wipe the slate clean and start again with the bare minimum that is relevant for the business today like a start-up would. Entire books could be written on working smarter, not harder, so I will not even go into that. But, in terms of how the general principles apply to business, I will throw out how we do it at Ecocoast.

This is an idea that has been around for decades, and maybe now, I hope is coming back into fashion – Zero-Based Budgeting. Again, I will not go into the background or what it is, only how we apply it at Ecocoast. We treat Zero-Based Budgeting as a forcing function. In our case, the forcing function is to constantly re-evaluate our resources, to question whether they are being deployed in the right areas and to force us to redeploy them constantly. This makes us take an active and a conscious effort in reallocation of resources and prevents the insidious cost creep and the constant loss of efficiency that plagues organisations.

In its basic form, we apply it in three stages:

- Improvements: These are investments in equipment, machinery, processes or systems that FREE UP resources, not add them.

- Growth: Is then obtained by using these FREED-UP resources in the areas with the highest potential return on investment.

- Risk: Is then how we as a company go about ensuring that the downsides are managed, the upsides are properly planned and that the above does not result in shortages that hamstring the business.

1. Improvements

Quite simply, we strip our budgets back to zero each year. By default, every department is forced to cut costs by 10-20%. Removing resources forces alternative thinking and a mindset of how to do more with less. For example, by forcing headcount reductions in divisions by default, it forces investment in equipment, machinery, automation or systems to compensate. If so, there could be a business case for investment that can be put forwards (more on this later). What other options are available? Can processes be improved? Are there tasks that we are doing now that add little or no value to our end product or to the client? Are we spending time going back and forwards for approvals with outdated sign offs that are no longer valid? So much time can be gained by simply mapping out a process clearly. By looking at this alone, we can immediately free up time and improve our internal efficiency, and quite often, this is enough.

2. Growth

In this phase, we take the surplus resources that have been freed up from the reductions and allocate them to a communal pool for reinvestment. Here we go from being in a position where we never have enough resources to having surplus resources to reinvest. We suddenly have resources – both capital and manpower to reallocate into the area with the most opportunity. But before we do this, we zero base one more thing – revenue.

Revenue is another area that is oh so easy to take the previous year and add 10%, or 15% or for the more optimistic Sales Directors, 50%. This is where we end up with the infamous hockey stick of growth. But what are we doing to achieve that? Can we hope that simply by showing up and doing our work clients will come flocking to us? No, Hope Is Not A Strategy! Hope without action leads to the equally infamous hairy back we see in most unrealised sales plans. An initial spike, and then the inevitable flatline. At Ecocoast, we assume the worst by default. We assume we will not grow next year and that our sales by product category will decline by at least 10% if we carry on business as usual. In order for a division to forecast higher sales than the previous year, there needs to be a special business case for that growth. What big moves are being undertaken to achieve that growth? What are we going to do differently? The steeper the growth projection, the more special the move should smell. In divisions that cannot justify an increase but are forecasting a reduction in sales, this forcing function loops back to further cost reductions, which by doing so, frees resources from unprofitable or declining segments of the business to be reallocated in growing segments.

So now we build our aspiration case for growth. What needs to be true for these divisions to grow? What big moves are needed to bridge the gap? These discussions drive annual strategic planning and investments. Here we debate this move versus that move before settling on only one, two or three big moves for the year or the upcoming period and throw everything and everyone behind achieving them. By only focusing on a few big moves, we avoid peanut buttering resources across everything that increases distractions and risk of failure.

3. Risk

Finally, there is risk. What could go wrong with our big moves? Here we look into the next period and conduct a retrospective. It is the 31st December 2019 and this move failed. Why? This forces us to identify key actions or blind spots that might cause us to fail, and ensures we cover as many bases as possible to mitigate risk and achieve success.

-

The above comments are thoughts I have had on the topic and are in no way meant to be a comprehensive argument on the subject. The approach definitely does not always work out perfectly, can never be taken in the extreme and will always be subject to exceptions. However, in a general rule, this is the way we approach our budgeting and investment decisions.