A New Image with an Old Twist: The Orientalist Implications of Eastern Europe's Social Block Architecture

In recent years, the culture of the former «social block» has been receiving more and more attention. The Western perspective explores not only the literature, music, cinema and languages of the region commonly known as Eastern Europe, but also its urbanism, architecture and urban environment. But how does this exploration happen? This text examines the tendency to portray Eastern Europe and, especially, its cities and architecture as something different, exotic, and distinct. The Belarusian case is no exception. However, it is peculiar in certain ways.

These representations shape the image of the whole Eastern Europe as something alien and outdated. This phenomenon is termed «new orientalism» by researchers, drawing an analogy with Edward Said, who wrote about the non-European East. Within the discourse on decolonisation, the focus is often on former colonies outside Europe, while overlooking the persistent colonial patterns and inequalities within Europe itself. This article analyses the concept of new orientalism in theory, as well as in relation to the cities of Eastern Europe, and exposes the mechanisms of orientalisation and the colonial gaze.

In recent years, the architecture of the «former social block» has enjoyed particular attention of the international community. Images of Yugoslav military monuments, Belarusian bus stops and bus stations, Soviet sanatoriums, and Bulgarian resorts tend to appear on social networks, in printed publications, music clips and science fiction films.

Buildings erected in the late socialism era have become a pop culture phenomenon. Now we can see them being regularly used as a silent romantic backdrop for anything from post-punk music videos to parkour classes and sci-fi movies.

Interestingly, this contradicts the earlier negative ideas about socialist architecture, which was dominated by monuments of the Stalin era and monotonous panel houses and shows the memorable buildings of the 1970s and 1980s as objects of true admiration, even romance.

These new representations have been termed a new form of orientalism, drawing on the concept of Edward Said. However, while Said talks about the Middle East, in this case we are talking about the European East, namely, the Eastern Europe.

In this text, I will define the concepts of orientalism and new orientalism. Then, I will describe the specific features of the colonial gaze on Eastern Europe, as well as show examples of how the oriental nature of the view of the architecture of the social block is manifested in today's representations. Finally, I will turn to the case of Belarus as an illustrative one to analyse the specifics of the colonial gaze in a number of other countries in the region.

Orientalism

Orientalism is a concept introduced by Edward Said in his namesake book (1978).

Orientalism is understood as a set of discursive practices which the West employed to structure ideas about the «East». It originated during the colonial period and promoted the colonial project and the colonial worldview, i.e. it was used to justify the political, social and cultural domination of the West over the East. Orientalism creates an image of the East as something Other, exotic, mysterious and different from the West. This contributes to the establishment and maintenance of unequal relations between the West and the East.

Edward Said identified several key features or characteristics of orientalism. Here are some of them:

Transformation into the «Other»: orientalism involves the process of artificially creating regions of «otherness», while the East (Eastern cultures, peoples and traditions) is reflected as fundamentally distinguishable, mysterious and exotic compared to the West. This creates a binary opposition between the West as a more advanced and the East as a more backward region.

Stereotyping, which means that orientalism relies on simplifications, generalizations and stereotypes about Eastern cultures and peoples. These stereotypes often depict Eastern cultures as static, backward and irrational, inferior to the West in terms of development. In this case, the East does not appear as a concrete geographical region, but rather as a matter of imaginary geography. That is, the East exists as such, and real people live in this region, but the European idea of this region is a typical cultural construct that contributes to maintaining unequal power relations and exploitation of the East by the West.

Essentialism: orientalism tends to essentialize Eastern cultures, that is, to view them as something monolithic and unchangeable. It overlooks the diversity and complexity of Eastern societies and tries to beautifully «wrap» different cultures as a souvenir.

The political, economic, and cultural hegemony of the West over the East and its representation. The West not only dominates the East, but also controls the ideas about it. At the same time, the West positions itself as a normative standard against which the rest of the world is evaluated.

Academism: Orientalism is not only a product of popular culture. It is also present in academic disciplines such as Oriental studies, anthropology, and history. Academic knowledge about the East was shaped under the influence of Western views and interests, often strengthening the existing power structures and relations.

Eastern European Orientalism

Edward Said's book greatly influenced the discourse on colonialism and the development of postcolonial theory. At the same time, for many years the latter itself remained a subject of criticism.

Among other things, Said is reproached for the fact that, speaking of the East, he refers to the Middle East mostly. Criticizing the imperialist perspective of the West, he nevertheless recreates the same one-sided way of knowledge generation in a bipolar East-West paradigm. Alltogether, territories to the west of Vienna and to the east of Russia do not exist for Said. The complex, intermediate position of Eastern Europe lacks analysis and consideration.

Nevertheless, Said's book inspired numerous subsequent works, some of which directly addressed Eastern Europe (Wolf, 1994) and the Balkans (Todarava, 1997; Bakich-Hayden, 1995; Bakich-Hayden and Hayden, 1992; Hayden, 2000), and spoke about such a concept as «new orientalism».

The New Orientalism

Rooted in the Edward Said's old concept (1978), this new orientalism still represents the East in terms of Western fantasies about the exotic Other, but the otherness in this case is described from an ideological rather than a cultural or racial viewpoint. Countries and regions are differentiated based on the extent to which they are adjusted to the free market and democracy. These criteria are generally determined by powerful players who set the rules of the game.

Furthermore, while earlier versions of orientalism were associated with the academic circles, this new wave is mostly aimed at a broader audience. It is more commercialized and linked to dissemination of images online (photos, memes) through mass media, social networks, etc.

Examples of Representations of Eastern European Architecture and Cities

Below are examples of various representations of Eastern Europe in popular culture (media, photo albums, quotes, memes, fashion and travel guides), which somehow refer to the orientalist image of the region.

Photography

The genre of photography that showcases the distinctive style of socialist architecture has been attracting more attention recently. In this regard, such projects as Nadav Kander's «Chernobyl», «Half Life» and «Dust» are extremely illustrative. The Calvert Journal published works by Sasha Mademoiselle and Sergey Kostromin featuring the «abandoned», as well by Sergey Novikov showcasing deserted Soviet cinemas. «Spomenik» by Jan Kempenaers and «Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed» by Frederick Chaubin.

The creators of these projects (a new generation of bold orientalist photographers), not unlike the colonial explorers of the past, wander through the «distant» and «desert» landscapes of Eastern Europe in search of ruins of a «long-lost» world.

They often describe their findings as something «otherworldly», «strange» or even «alien», thereby creating a new image of the post-socialist world as a land of bizarre, mysterious objects that the «intelligent» Western mind is unable to comprehend. This imagery spread so widely in the media that now it dominates the ideas of socialist architecture not only in the West, but also in the very east of Europe.

A leading media like The Guardian (for example,here andhere) displays fascination with the surreal and otherworldly nature of these structures. Parallels are drawn between them and «alien landing», «circles in the fields left by aliens», as well as Pink Floyd album covers. These structures are also compared with images of satellites, space rockets and flying saucers. The term «ruin porn»adressed in the «Soviet Ghosts» by Rebecca Bathory, highlights a certain voyeuristic appeal of these neglected buildings. The architecture of institutions such as the Minsk Polytechnic Instituteis described as «a mighty passenger ferry breaking through the frozen Belarusian river». These structures emphasise the grandeur and severity of their socialist design. Thus, the Western media present post-socialist architecture as an obsessive, albeit visually fascinating ghost story, told through a brick and cement Grove, imbued with futuristic inertia and a sense of Soviet history.

Memes

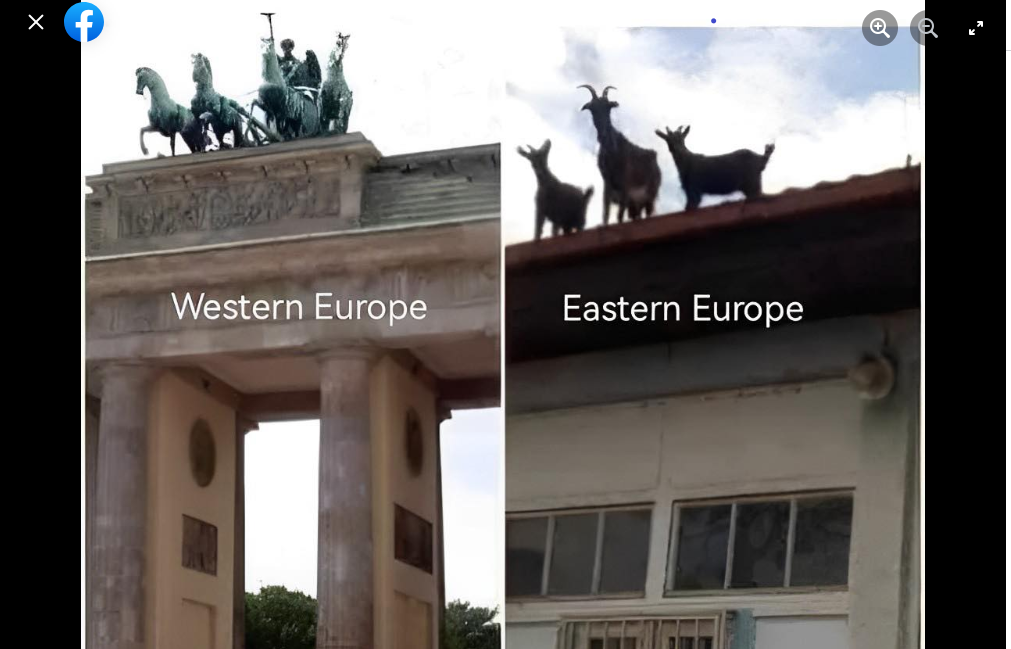

Examples of the orientalist view of Eastern Europe can also be found in a completely different domain of pop culture-such as humor production. Memes from publics like Squatting Slavs In Tracksuits, which actively exploit the orientalised image of residents and cities of Eastern Europe, are quite illustrative. In this case, we are talking more about self-orientalising*, because this public was created by Eastern Europeans. However, it is popular with international audience.

*The term «self-orientalising» refers to the process whereby people who are the object of orientalism (in this case, Eastern Europeans) adopt an orientalist perspective or stereotypes about their culture and begin to reproduce them. This may occur under the impact of external orientalist prejudice and manifest itself in the form of imitation thereof. Thus, self-orientalising becomes a form of internal colonialism that supports and spreads inequality and distorted view of culture and identity.

The Squatting Slavs public reflects the volatile mix of feelings of Eastern Europeans about their post-socialist heritage and peripheral position in Europe: from annoyance that they are seen as somehow different, second-class, to self-flagellation and self-demonisation, nostalgia for the Soviet past and self-orientalising/self-exotisation. Abstract «Slavs» are used as references for such humour, even though it exploits visual objects from non-Slavic cultures that are also clearly not considered as «examples of Western culture». For instance, there are photos of skyscrapers in Tbilisi, Georgia, with captions like «the dream house of a Slav».

Memes About «Brutalism»

Memes that mock the phenomenon of romanticising brutalism in the West, especially among the «left-wing» audience, are also peculiar. At the same time, the term «brutalism» as a definition of the style of Soviet/socialist architecture is often used erroneously, since in strictly formal terms there are more elements of modernism in it, while only certain buildings were truly brutalist. This is presumably because, since the mid-2000s, there has been a trend of fetishising brutalism in general, not only Soviet/socialist, architecture. It appears that in this case the architecture of Eastern Europe, which reminds the Western eye of the brutalism familiar to it, is perceived as something familiar.

Gosha Rubchinskiy

In the West the term «post-Soviet» became especially popular in a certain period of the 2010s, when people like the Russian fashion designer Gosha Rubchinsky burst onto the fashion catwalks, with streetwear collections rich in orientalist Soviet references. The title of Rubchinsky's very first fashion collection, «The Evil Empire» released in 2008, echoed a speech by US President Ronald Reagan during the Cold War, which condemned the «totalitarian darkness» of the Soviet Union.

Rubchinsky was just one of the many creators who, through street culture, tried to portray Eastern Europe in an orientalist way as «poor, but sexy». Alongside that, he fetishized an imaginary view of the Soviet, and not reality as such.

Another example of the aestheticization of post-Soviet cultural artifacts is the use of old panel high-rise blocks in the visual design of the post-punk music scene (examples can be found here, here and here). In this case these blocks often become «protagonists» of the videos, adding a touch of pessimism and predestination to their overall atmosphere.

What is the problem with this particular representation of Eastern European architecture and cities?

The examples shown recreate myths about Eastern Europe as a kind of alien, yet supposedly simple, imaginary space. They rely on the same orientalist patterns described by Edward Said. Thus, they construct otherness, exoticism (Eastern Europe as a land of strange, extraterrestrial objects), and backwardness (socialist architecture is presented as a product of an extinct social system, the ruins of a long-lost world). They are also marked by Stereotyping, Desemantisation (the loss of primary meaning and artistic value), and Essentialization (the tendency to represent eastern European cities as something monolithic and static, ignoring the changes that happen to them).

This could be seen as orientalism in its classic form — the portrayal of the whole complex culture of the region as a homogeneous Other. At the same time, the West establishes hegemony over how this region is described and represented.

What does this mean for the reproduction of social inequality in Europe and the wider discussion about racism?

The problem of orientalisation of Eastern Europe is connected with such a concept as Eastern Europeanism, which Ivan Kalmar resorts to in his book «White But Not Quite: Central Europe's Illiberal Revolt». By «Eastern Europeanism», he means «prejudice against Eastern Europe, which conjures up the image of a desperate, distressed region exploited by a corrupt elite, where most people will stop at nothing for a euro or a dollar». Eastern European societies are portrayed as «demoralised populations who, simply due to cultural traits, tend to support autocratic governments. They appear innately anti-semite, islamophobic, homophobic and racists».

Eastern Europe is depicted as the direct opposite of the West.

In this context, prejudice concerning Eastern Europe acts as a kind of cultural classifier, whereby every country to the east of Western Europe seems less and less «Western» (and therefore less civilized), inter alia, in the local residents' own view. East Germans consider themselves more Western than the Czechs, who, in turn, consider themselves more Western than the Slovaks, who treat Belarusians and Ukrainians similarly, until it comes to the «ultimate» Eastern Europeans — Russians.

When the inhabitants of this region say that they consider themselves to be «central Europeans», they mean that they are different from Russians and want to be considered more «Western». However, the West does not always take this into account.

It is possible say that these biases fit into the concept of xenoracism. Although Eastern Europeans are predominantly white and enjoy many of the privileges of a white person, they nevertheless suffer from discrimination and racist stereotypes in the West and feel themselves positioned on the periphery of the Western world.

Belarus

The Belarusian case has peculiarities even among those of other Eastern European countries. This is a blatantly authoritarian system of dictatorship, with close ties to Russia and linguistic russification. Altogether, it turns Belarus into a perfect — in terms of orientalisation — example of a country where nothing has changed since the days of the «Soviet Union». At the same time, the ignorance about Belarus and its small size allow its local historical and cultural complexity and originality to be more easily overlooked, than those of Russia.

A striking example of the orientalist depiction of Belarus in the West is the YouTube bloggerBald and Bankrupt, who became famous for his travels to Belarusian cities, towns, and villages.

In his blog, he seeks to show the seemingly unobvious side of Belarus, which one will not find in tourist guides. At the same time, he often uses clichés about Belarus as a «Soviet museum» and confuses Belarus with Russia.

Here are some examples of phrases he accompanies his stories with:

«Time travel back to the USSR»,

«Welcome to the Soviet Union»,

«Nothing has changed since Soviet times».

Videos on his channel show Soviet cafes, Soviet hotels, bus stations, sleeping areas, broken asphalt in slushy and wet February weather. The author draws attention to the green paint on the walls, which decorators «liked to use in Soviet times». He seems to be surprised by the low prices and Soviet-like service. His videos create an impression that Belarusian cities consist only of such «islands of socialism», although in fact they are not so many in number.

«No one has the means to create these places anew, so you can see the real Soviet architecture (decor, furniture, and curtains)»

It is worth noting that he shows the Soviet heritage with such genuine enthusiasm and admiration that it even evokes sympathy. It may seem that he is doing a good thing, trying to educate the Western audience about «real» and «true» Belarus. But in the end, he also constructs the image of Belarus as a backward, exotic region that is stuck in the Soviet past, in the spirit of Eastern European orientalism. If you take an outside look at these representations, you might think that before the Soviets, Belarus did not exist at all. Interestingly, he pays attention and includes in the blog not everything that he sees around, but only those aspects of the Belarusian reality that seem to him the most characteristic and unusual, because such exoticism helps to attract more subscribers. But for his audience, which does not see the whole picture, this creates the image of the «real» Belarus, which they can later take at face value.

Occidentalism / An «Eastern» View of Belarus

It is interesting that if one looks at the representations of Belarus in the «East», for example, in the Russian media, they will see, on the contrary, a very «western» image of Belarusian towns and cities. If the Western media pay attention to the extent to which Belarus is «stuck in the Soviet past,» Russian ones depict some kind of future Belarus (a little romanticized ass well, though).

An illustrative example of such a representation can be found in the YouTube blog by @Margo.tikhonova. Belarusian society and its cities look ultramodern, European, and progressive, which is sometimes quite unexpected and surprising even for Belarusians.

Here are some of the personal observations Margo shares, describing the differences between Belarus and Russia:

The famous «cleanliness», which the locals have grown rather tired of, is presented as a kind of a benefit and a discovery in itself. As if it were something inherent in Belarusians since ancient times: «cleanliness is something in the mentality of Belarusians». «They don't litter, everyone tries to keep their surroundings tidy». In this context cleanliness acts as a certain marker of civility, Europeanness: «everything is very civilized», «just like in Europe».

Safety. The author pays attention to the fact that in Belarus, compared with Russia, it is much «safer and calmer». She is surprised that «people leave their belongings on the tables in the cafe freely and are not afraid that they will be stolen» and «that outside cities and towns people do not lock their houses and cars». She links these observations, among other things, to the fact that Belarusian society has no strong social stratification and that «people are more polite and intelligent».

Positive driving experience. Somehow unexpectedly for local residents, the blogger found it significant that there are no traffic jams in Belarusian cities, and that the roads are of high quality and cleaner: «even the roadsides are cleaned». She also notes that Belarus has a strong driving culture, and that speed limits are observed.

Based on the above, she concludes that Belarus is a great place for tourism and relocation.

Although this image of the country may seem flattering at first glance, it fits perfectly into the same geographical constructs and cultural stereotypes that we discussed above. However, in this case we are no longer talking about orientalism, but about occidentalism. Occidentalism is a stereotypical image of the West/Western world, which emerged as the opposite of the concept of «orientalism». As a rule, occidentalist stereotypes are also based on romanticization and a stereotyped view of the region. The only difference is that they are of a more favourable and complimentary nature when it comes to western regions compared to eastern ones.

Occidentalist representations of Belarus are also clearly exemplified by Russian tourist sites. If one looks at tours to Belarus offered by Russian companies, they can notice a significant emphasis on the «Western», medieval cultural heritage of the country, such as visits to medieval fortresses, castles, churches, and Franciscan monasteries. Recently, the list of «attractions» has been supplemented by stores of Western brands that are no longer available in Russia.

This is somewhat reminiscent of the image of the Soviet «Baltic States» and the way Baltic countries were presented in Soviet times as «the West», but «their own», Soviet one. Clearly, this kind of occidentalism did not mean that the Baltic republics were recognised as subjects, and that they had the right to make independent decisions The stereotyping of Belarus from both perspectives should be critically questioned, even if it is flattering rather than dismissive.