Family : Brassicaceae

Text © Prof. Giorgio Venturini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Is it a rose ready for a "can can" ? No, it is a leaf cabbage © Giuseppe Mazza

In this way G. Orwell introduces us in the squalid housing of Winston Smith, the protagonist of his novel “1984”.

In our imaginary the smell of cabbage is the emblem of the lifestyle of the more modest classes and of the neglect of the housings: we shall soon see how the preconceptions of this food are unfounded.

The genus Brassica, native to Europe, Central Asia and North Africa, includes some tens of species, whose definition is complicated by the ease of hybridization. As an example we recall the common cases of hybridization between three species common in our climates, the Brassica nigra, Brassica oleracea and Brassica rapa, who originate three species, Brassica carinata, Brassica juncea and Brassica napus.

Many species of Brassica are cultivated for alimentary, zootechnical or industrial use and this practice has diffused the genus practically all over the world.

The wild Brassica oleracea L. 1753 is a biennial plant (but the cultivated forms are harvested during the first year, excepting the plants intended for producing seeds), with a robust basal rosette with big fleshy leaves, that, being able to store water and nutrients, represent an adaptation to the arid and rocky environments of its habitat.

By the second year the nutrients stored are utilized for producing a long floral axis, up to more than 2 metres tall. Completely glabrous plant. Flowering stem from 30 to 200-300 cm tall, woody at the base, glabrous, covered by the scars of the dead leaves.

Basal leaves with usually entire terminal lobe, up to 40 cm long, fleshy and glaucous, usually petiolate, lobate, with 1-2 pairs of lateral segments and a bigger terminal segment, entire or crenate at the margins, that is with rounded and little marked teeth. Cauline leaves ovate-lanceolate or oblong, entire, sessile or more or less petiolate depending on the variety.

Today you can find it in different colour pairings, suitable for flower beds and bouquet © Giuseppe Mazza

Habitat

Rocky environments from the coast up to 1200 m of altitude. Blooming between March and April. The plant is spontaneous in the coastal regions of southern and western Europe. Due to its high tolerance for salt and limestone it often occupies the coastal limestone cliffs. In Italy is present in Liguria, Tuscany, Emilia, Marche, Lazio and Sicily.

Brassica oleracea is amply cultivated in most of the world with numerous varieties, or better groups of varieties, among which we recall here those more commonly cultivated in Europe:

Brassica oleracea var. acephala (several varieties of leafy cabbages, among which the lacinato kale or the leaf cabbage)

Brassica oleracea var. italica (i.e. the broccoli)

Brassica oleracea var. botrytis (the cauliflower and the Romanesco broccoli, with numerous varieties)

Brassica oleracea var. capitata (i.e. the headed cabbage, used for the preparation of the sauerkrauts)

Brassica oleracea var. capitata rubra (the red cabbage)

Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera (the Brussels sprout)

Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes (the kohlrabi)

Brassica oleracea var. sabauda (the Savoy cabbage)

Most of the varieties of cabbage get on the markets during the cold months and historically the cabbages have been the most consumed vegetables during the winter.

To the varieties acephala belong plants devoid of the central “head” typical of other varieties (“acephala” in Greek means without head). To this group belong besides the Tuscan lacinato kale various other forms cultivated for the edible leaves or for ornamental use, in such case thanks to the brightly coloured leaves.

In some regions, like the Canary Islands, some varieties of cabbage like the Jersey cabbage get to produce a stem even three metres tall and are utilized for the production of walking sticks.

The unusual curly cabbage, edible, also named scotch, it belongs at the same group. Rich in vitamines, minerals and precious antioxidants it should deserve a larger diffusion © Giuseppe Mazza

To the group capitata belong forms producing a head (“capitata” from the Latin caput, head) formed by countless leaves thickly compacted due to the extremely reduced internodes between the leaves. The leaves are very fleshy and carry out a function of accumulation of nutrients. Some varieties are of red-violaceous colour due to the presence of pigments called anthocyanins.

To the group italica belong forms having big floral heads, usually green, arranged to form a tree-like ramified structure that branches off from an edible stem. These forms have been selected probably by the Romans in ancient times and at the Empire times were widely consumed throughout the territory. The name “italica” refers to the geographical origin of these cultivars.

The variety gemmifera includes forms producing globular axillar buds, formed by strictly imbricate leaflets.

The variety gongylodes (the kohlrabi, from the Greek “γογγύλος gongýlos” round, rounded) includes forms where the lower part of the stem produces a roundish edible swelling from where detach some leaves. The colour may be white, green or violaceous. It must not be mistaken with the celeriac (Apium graveolens var. rapaceum) that is an Apiaceae, therefore of the same family as the celery or the carrot.

The variety sabauda (the Savoy cabbage) includes plants similar to the variety capitata but characterized by ruffled leaves and with showy veins. The name refers to the origin of the cultivar in northern Italy (Savoy).

Etymology

“Brassica” from the latin name of the cabbage. The origin of the name is uncertain, possibly from the Celtic name of the cabbage, bresic. “Oleracea” in Latin adjective from “olus, oleris”, vegetables, of the vegetables.

Cabbage: from the Latin, caulus, in turn coming from the Greek kaulós, ‘stalk, stem’.

Broccolo from the Italian term brocco, that is bud (term nowadays outdated, but we recall Pascoli’s poetry “o Valentino vestito di nuovo come le brocche dei biancospini!”), (Oh, Valentino, newly dressed like the buds of the hawthorns!). Broccolo in fact comes from brachiolum, in turn diminutive of brachium, arm or branch, clear reference to the shape of this vegetable, similar to a small tree.

The broccoli must not be mistaken with the broccoli rabes, or rapinis, or turnip tops, very utilized vegetable in Lazio, Campania and Puglia regions, that are the leaves and the inflorescences of Brassica rapa.

As well Black cabbage, tipical of Tuscany kitchen, belongs to Brassica oleracea var.acephala, the leaf cabbages © Giuseppe Mazza

The domestication of the cabbages has probably started since the Neolithic in the fertile crescent and is a striking example of the possibilities offered by the artificial selection that operates on the base of the variability.

Inside the natural populations of the wild cabbage exists a variability, for instance for what concerns the ramification of the stem, the presence of lateral inflorescences, the size, the fullness and the roughness of the leaves, the duration of the vital cycle.

The man has selected some characters of the spontaneous forms, chosing the plants that presented the wished qualities and duly crossing them, till to obtain the numerous modern varieties.

The long and bullate leaves, very dark, are appropriate for salades, potatoes and cheese croquettes, soups or even, for the substance, for unusual chips to garnish appetizers © Giuseppe Mazza

In the old Rome they did amply utilize and appreciate various varieties of cabbages, as attested by Pliny. In the “Naturalis Historia”, in fact, this author, reporting also the opinions of Pythagoras, Hippocrates and Cato, explains that the Romans and the Greeks before them used the cabbage as food and as medicine since many centuries.

He knows several varieties of cabbages, smooth, wrinkled and with enlarged stem. The medicinal virtues, ingested or for external use, cooked or raw or mixed with various ingredients, are numerous, against the head ache, stomach ache, the cancer, the wounds and the fractures, the insomnia, the snakebites, the poisonous mushrooms, the gout and for many other applications. Particularly beneficial to the nerves is then the urine of who has eaten cabbages and, if used for washing the children will have them growing stronger. After Cato, when the cabbage proved ineffective against a disease, you could only use magic.

An important virtue is then against the drunkenness and its after-effects: after having eaten some raw cabbage it was thought that it was possible to drink wine at will with no consequences. As proof of this belief an image of the cabbage was accompanied by the written sentence “ne gravet ebrietas” : “so that the drunkenness is not too annoying”.

Among the cabbages, after Pliny, the best as taste, but difficult to digest, is the “cyma” (probably the broccoli), that, inter alia, with only one application treats the bite of the rabid dogs.

This plant, cornerstone of the feeding at the times of the Republic, in the times of the Empire was actually consumed mainly by the rabble: that is why still now it is used for indicating something of no value in many common expressions such as “not worth a cabbage” or “I don’t give you a cabbage”.

In the times of the Empire, even if Lucullus did not deem them worthy of his table, some considered the cabbages as a titbit, like Tiberius’ son, Drusus who, it seems, made an excessive use of them. Apicius, the celebrated gourmet, gives us various recipes for cooking the cauliculi, that is the tender buds of the cabbages. It was also consumed, when necessary, the wild cabbage: during the celebration of one of Julius Caesar’s triumphs his legionaries, to criticize the low level of the rations, staged pranks where they reproached the general of having survived by eating wild cabbages (during the triumphs the winning legionaries were allowed to joke and tease their leaders). In the 305 A.D., the emperor Diocletian left the power when 62 and retired in Split, where had built an impressive palace, still existing, and spent his time taking care of his work in his country. Urged to get back at the guide of the Empire, he refused saying that his cabbages gave him more satisfaction than the power.

Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica), with its typical branched structure, as a small tree, is on the contrary among the most known varieties. It used to be grown by ancient Romans but with few exceptions was eaten by peasants only. Presently it is widespread all over the world and is the one who conquered China and Asian market © Giuseppe Mazza

Along the old legends linked with the cabbages, it was told that Lycurgus, King of Thrace, decided to cut all his vines (maybe he had decided to stop drinking?). The god Dyonisus, to whom the vines were sacred, was offended and for revenge bound Lycurgus to a stump. The prince began to cry and from his tears were born the cabbages that since then were always enemies of the vines. After the popular belief the cabbage planted close to a vine did go way growing in the opposite direction (possibly this legend explains why the Romans deemed the cabbages a remedy against drunkenness). Actually, the myths related to Lycurgus and Dyonisus are many but are all relevant to a serious enmity and associated to the stump or the shoot of the vine.

Brassica oleracea var botrytis is the classical cauliflower with a moltitude of recipes © Giuseppe Mazza

About its diffusion in Europe, the data are contradictory, in fact, while after some historians only by the middle of the ‘500, thanks to Catherine de’ Medici, the cultivation of the cabbages started in France and only by the end of the 18th century these vegetables should have reached England, reliable information witness that already in 1541 the cabbages were introduced in Canada by the French and in 1669 by the British in their North American colonies.

For lovers of the uncommon, fanatics of the Brassica oleracea var. botrytis, today we find also yellow-orange and purple varieties © Giuseppe Mazza

It is possible that the cabbages have been introduced in Asia in relatively recent times, for instance they reached India thanks to the Portuguese probably around the 15th or 16th century and in Japan they were still unknown in 1775.

Also the varieties of cabbage presently more diffused in China and in other Asian countries, such as the Chinese broccoli kai-lan come from those imported from Europe (not to mistake with the Chinese cabbage Brassica rapa var. chinensis and pekinensis that probably have an old and local origin (already mentioned in treatises on Chinese medicine of the early sixteenth century).

Macerata cauliflower belongs to the same group, similar to roman broccoli but more roundish © G. Mazza

The President George Bush sr. will be remembered as one of the fiercest enemies of the broccolis: in 1990 he forbade their presence on the presidential plane Air Force One and declared:

” I do not like broccoli. And I haven’t liked it since I was a little kid and my mother made me eat it. And I’m President of the United States and I’m not going to eat any more broccoli.”

In response the growers of broccolis of California sent 10 tons of broccolis to the White House. It seems that this was an obsession for Bush, seen that during his term he cited the broccolis at least 70 times.

Nutritional aspects

The cabbages are a food very rich of vitamins, in particular A, B, C and K whilst they are poor of carbohydrates, fats and proteins.

The caloric intake is scarce. The low contents in carbohydrates renders the cabbages valid substitutes of the potatoes and of the flour products in the diets with low caloric contents. Fairly good is also the contents of fiber.

Even if the nutritional properties of the different varieties of cabbages are basically similar, we note some differences in the vitamin contents and in those of other substances.

Only as an example, we remind that the red cabbage is particularly rich of vitamin C and of antocyanins.

The high contents in vitamin C of the cabbages has represented a very important resource in the human nutrition, especially thinking to the populations of central-northern Europe for whom, during the winter months, this plant has been the only available fresh vegetable and consequently the main source of vitamins.

The scurvy, devastating disease due to the lack of vitamin C, for centuries has made victims among the seamen, who during their long voyages had no access to fresh vegetables, or among the poorest North European classes, malnourished for what concerns the fresh vegetables. It is estimated that between the ‘500 and the ‘700 about 2 millions of seamen have passed away due to the scurvy. Only as an example we remind the case of the English admiral Anson who during his voyage around the world (1740-1744) lost, mainly due to the scurvy, about 1300 of his 2000 seamen.

The cabbage has played the key role in eradicating this disease, with the most important example being represented by the voyage around the world (1768-1771) of Capt. James Cook.

Roman broccoli has the typical look of a fractal, a complex structure that repeat itself in its shape always in the same way but in different scale © Giuseppe Mazza

For the purposes of Cook’s voyage it was impossible to think to the fresh vegetables, so was prepared some dried lemon juice that proved useless (nowadays we know that the dehydrated lemon juice loses most of the vitamin contents), remained the sauerkrauts, thanks to which the Master, with his vessel Endeavour, did not loose due to the scurvy none of his seamen.

Cook embarked about 3,5 tons of sauerkrauts (fermented cabbages), that, with their rich intake of vitamin C, prevented the occurrence of this disease. (The fresh cabbage is itself a good source of vitamin C, but the fermentation process increases very much its contents and the bioavailability).

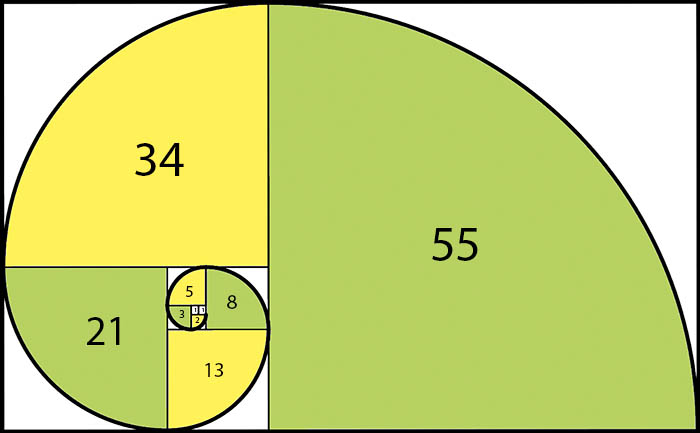

Broccoli tops are set according to the famous spiral of the renowned mathematician Leonardo Pisano called il Fibonacci (Pisa 1115-about1235), shaped by a series of arches with growing radiuses according to the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the previous two. Figures shown in the picture are indeed the radiuses of the arches © G. Mazza

Here are his words: “The Sour Kroutt, the Men at first would not eat it, until I put it in practice – a method I never once Knew to fail with seamen – and this was to have some of it dressed every day for the Cabin Table, and permitted all the Officers, without exception, to make use of it, …… but this practice was not continued above a Week before I found it necessary to put everyone on board to an allowance; for such are the Tempers and disposition of Seamen in general that whatever you give them out of the common way – altho’ it be ever so much for their good – it will not go down, and you will hear nothing but murmurings against the Man that first invented it; but the moment they see their superiors set a value upon it, it becomes the finest stuff in the world and the inventor an honest fellow.” Actually, Cook during his voyage lost no opportunity in sourcing fresh vegetables, all excellent sources of vitamin C, so during their stay in the Hawaii, often embarked sweet potatoes, bananas and fruits of the breadfruit tree, whilst during the circumnavigation of New Zealand collected huge quantities of sea celery (Apium prostratum).

The use of the sauerkrauts on the vessels became later the norm and so also the whaling ships were able to face hunting cruises lasting three or four years thanks to the stocks of sauerkrauts.

Headed cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata), with numerous leaves thickly compacted, is used to prepare sauerkrauts. Rich in C vitamin granted to sailors, formerly, to prevent scurvy © Giuseppe Mazza

The Dutch and the Scandinavians already were aware of the alimentary virtues of the cabbage for the prevention of scurvy during the long winter months and during the long navigations, but apparently the information had not reached all: after the British naval officers, still in ‘800, the best prevention was given by the discipline and by the hard work.

Pharmacological properties

The cabbages contain various substances with interesting properties, as antioxidants, potential anticancer and especially detoxifying. Among these substances we recall the glucosinolates, such as, for instance, the glucoraphanin, glucosides containing sulphur, that have an important role in the defence of the cabbages and of other Brassicaceae against animal aggressors.

These substances are themselves inactive when the plant is injured or crushed, for instance by the bite of an animal, they transform by an enzymze, the myrosinase, originating substances having a sour taste and with antiparasitic properties (and beneficial to man). This phenomenon is made possible by the fact that the glucosinolates are contained in compartments different from those containing the enzyme. When the tissues of the plant are injured the enzyme mixes with the glucosinolates and produces substances like thiocyanates and isothiocyanates (for instance the sulfuraphane), acrid, and consequently repellent for the predator, and with insecticidal properties.

The transformation of the glucosinolates may also happen in the rumen of the ruminants done by the enzymes produced by the bacterial flora. In our gut the transformation is extremely modest due to the more reduced bacterial flora and of the shorter contact of the foods with this.

Section of Brassica oleracea var. capitata rubra, the red cabbage, rich in healthy anthocyanins © G. Mazza

The products of the hydrolysis of the glucosinolates have important pharmacological effects, especially for their capacity to activate the systems of detoxification against many harmful substances. Being volatile and equipped with a pungent odour, these substances generate the characteristic odour during the cooking of the cabbages and are responsible of the spicy properties of the mustard and of other Brassicaceae such as the Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.).

Our sense of smell is very sensitive to these substances and this may represent a drawback for the culinary use of the cabbages (there are recipes, more or less effective, aimed to reduce the uncomfortable inconvenience, for instance the acidification with vinegar or lemon of the cooking water). Actually, responsible of the odour are several sulphurated compounds deriving from the thermal degradation of the glucosinolates, especially sulphurated hydrogen and dimethyl- and trimethyl sulphide.

The contents in glucosinolates changes depending on the variety of the cabbages and of the stage of ripening, the buds of the broccolis, for instance, are richer than the ripe broccolis and the cauliflowers are an excellent source. The most important factor is however that linked to the necessity that the glucosinolates are transformed in the active products such as the sulfuraphane.

We have seen that of the transformation are responsible enzymes present in the cabbage and we know that the enzymes are degraded by the colour. Hence the quantity of sulphuraphane (or similar products) reaching our body is much bigger in the case of raw cabbages (or, also even if less, in cabbages submitted to very short steam cooking) than in boiled cabbages, where the enzymes are completely inactivated.

It must be therefore remembered that the cooking, inactivating the enzymes present in the cabbages and that are necessary for converting the glucosinolates, makes these foods losing most of the detoxifying or anti-cancer properties that are attributed to them. In this sense it is preferable to consume them raw in salad or however little cooked.

The kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes) has a edible and roundish trunk © Giuseppe Mazza

The beneficial effects of the sulphuraphane of the other isothiocyanates released by the glucosinolates present in the cabbages are manifold and important, seen that these substances have detoxifying, antioxidant and antiinflammatory properties. The detoxifying action is due to the fact that the sulphuraphane stimulates strongly the production of the enzymes in charge of the deactivation and the elimination of toxic and carcinogenic substances such as the aflatoxins and many more.

For this reason, and for the antioxidant and antiinflammatory properties and also on the base of epidemiological and laboratory studies, the cabbages are considered as good candidates in the prevention of many kinds of cancer, including those to the bowel, the prostate, the ovary and the lung.

The cabbages contain also other substances with antiinflammatory activity, like for instance the anthocyanins, particularly abundant in the red cabbage, and other polyphenols. Another substance coming from the glucosinolates of the cabbages is the indole-3-carbinol, to which are ascribed anti carcinogenic, anti atheromathosis, and beneficial effects against the lupus erythematosus.

The cabbages might also be useful in treating pathologies like gastric ulcer. The cabbage juice (or the raw cabbage) in fact, thanks to the contents in S-Methylmethionine (this substance is also called vitamin U, but is not a vitamin), has the property of accelerating the repair of the peptic ulcers.

The assumption of cabbages may however have also negative effects for the animals and in some measure also in the man. The derivates of the glucosinolates assumed with the cabbage have in fact an antithyroid action, as they interfer with the uptake of the iodine necessary for the thyroid hormone synthesis. The thyroid insufficiency obliges the pituitary gland to secrete a hormone (TSH) that stimulates the growth of the thyroid tissue and this may cause an enlargement of the gland, that is the goitre. For this reason, the cabbages are considered as goitrogenic foods and therefore their use is discouraged to those having hypothyroidism. The antithyroid activity of the cabbages is not such to cause harm to healthy individuals, but can represent a problem in the cattle breeding, where the quantities of Brassicaceae used may be very great.

Brussel sprouts field (Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera) © Giuseppe Mazza

Studies are under way for producing Brassica with low contents of SMCO to be utilized as animal food.

Even if the cabbages represent an excellent food, an excessive alimentary assumption of cabbages can cause production of intestinal gasses, resulting in bloating and flatulences. This phenomenon is caused by the presence of the raffinose carbohydrate, a trisaccharide that the enzymes of our gut cannot digest and that then is exposed to fermentation by the intestinal bacterial flora, with production of gasses such as methane, hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

We must also not forget that the cabbages assume minerals from the soil among which also heavy metals. Plants grown in polluted soils may be the cause of poisoning.

It is interesting to note that, whilst most of us appreciates the taste of the various types of cabbages, some find them sour or having a too strong taste. It has been discovered that these persons, called “supertasters (supersensitive)” have the tastebuds of the tongue particularly sensitive to the sulphur compounds of the Brassicaceae.

The sulphur compounds present in the cabbages are eliminated through the urines and, after having been modified in the kidney, are then responsible of the odour assumed by the urines after having eaten in particular the Brussels sprouts.

Traditional medicine

Apart the previously cited uses done by the old Greeks and Romans, also in the Middle Ages and in modern times the traditional medicine has widely used the cabbages for internal use as well as for external applications, for instance for rheumatisms, breast engorgement, sore throat, colics, ulcers, depression. During the first world war the British soldiers used cabbage leaves compresses for treating the trench foot.

A very diffused utilization of the raw cabbages is that as anthelmintic, that is for the elimination of the intestinal parasites such as pinworms, roundworms and tapeworms.

The cabbage as pesticide

The glucosinolates and their degradation products have fungicidal, bactericidal and nematocidal properties and are one of the weapons the Brassicaceae use in the struggle against their parasites. When an animal chews the tissues of a cabbage, or when a parasite in general damages the tissues, it causes the mixing of the glucosinolates with the enzyme that transforms them in isothyocianates that will have a repellent or toxic effect.

Globular axillary buds, show small leaves strictly scaled © Giuseppe Mazza

Of course, in the eternal armaments race between parasites and hosts has evolved a specialized fauna of insects able to evade the defences of the Brassicaceae. Examples are the common cabbage butterflies such as those of the genus Pieris, but also some aphids, coleoptera and many others.

The cabbage butterflies are not affected by the toxicity of the isothiocyanates and their larvae even are favoured by them. Some Pieris, nourishing of Brassicaceae accumulate in their tissues these substances that then defend them from the birds, their predators.

One of the mechanisms exploited by some parasites such as the harlequin cabbage bug (Murgantia histrionica) is that of producing an enzyme transforming the glucosinolates in compounds not toxic instead of in isothiocyanates.

Cabbage parasites

Among the parasites that may attack the several varieties of the Brassica oleracea we can remind, as an example, the following: Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV), Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus (TYMV) and bacteria of the genus Erwinia, responsible of the rottenness of the cabbages.

Numerous are the fungal diseases like the Downy mildew (Peronospora brassicae) , the Alternariosis (Alternaria brassicae; Alternaria brassicola) and the powdery mildew (Erysiphe cruciferarum.) Among the insects are important some Aphids like the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) and the cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae), and above all Lepidopterans such as the Cabbage moth (Mamestra brassicae), the Cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) the Small white (Pieris rapae). The small lepidopteran (Plutella xylostella), of Mediterranean origin but now diffused in all the world, is one of the most dangerous parasites for the cabbage crops (it eats only plants producing glucosinolates) and, with no treatments can get to destroy the 90% of the product.

We remind also coleopterans like elaterids (Agriotes spp.), curculionids (Baris spp.; Ceuthorrhyncus spp.) , dipterans among which the cabbage fly (Delia radicum), and hemipterans like the harlequin cabbage bug (Murgantia histrionica) and finally nematodes of the genus Meloidogyne.

In cooking Savoy cabbage (Brassica oleracea var sabauda) is one of the most adaptable vegetable. It matches with mithical and traditional recipes but also with sushi © Giuseppe Mazza

The romanesco broccoli has the typical look of a fractal, a complex structure that repeats in its shape always identically on different scales: enlarging any part thereof we obtain a figure similar to that of the whole. In other words, a fractal is a conglomeration of itself copies in different scales. If we examine a single top of the broccoli, it resembles a mini broccoli with all its very small tops.

Fom an evolutionary point of view the fractal organizations in nature explain with the fact that the nature proceeds with the maximum of economy, proposing the same genetic sequence coding of a certain structure for a ‘n’ number of times. The fractals have the property of producing complexities starting form single repeated rules. If we observe the arrangement of the tops in a broccoli we see that the rules of self-similarity operate with a spiral pattern, generating an elaborate architecture.

Tales, legends and medicinal properties. Even if under cabbage leaves you cannot find babies, these are precious for life. A B C and K vitamins, antioxidant properties, anti-cancer virtue and detoxifying agents © Giuseppe Mazza

All organs of the plant have origin in the apical meristem through a process very well organized and genetically governed. The cells composing the meristem, on the apex of the stem, divide many times and their descendants differentiate in specific cellular types to obtain complete and functional, like the tops of the broccoli. It is in this very first stage of development that determines the final geometry of the plant, with the outlines arranged in optimal functionally positions and distances.

But how can the plants generate such patterns? Tests conducted on the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (also a Brassicaceae) suggest an essential role for the vegetal hormone auxin.

The accumulation of auxin in particular regions of the meristem determines the position where will be started the differentiation of a new outline. In the meantime, the transportation of the hormone towards the outline itself will produce a strong reduction of its concentration in the surrounding regions. In this way we shall have an inhibitor field that prevents other outlines in the offing. Then it will be necessary to wait till when the primordi grow and get away from the centre of the meristem to have the appearance of regions with a concentration of auxin sufficiently high to allow the formation of a new primordium. The combined effect of activation and inhibition of the differentiation ruled by this hormone, determines a spiral geometry evident in the Romanesco broccoli.

All the small tops are positioned around a spiral that satisfies the requirements of a Fibonacci spiral, that is a series of arcs with radii following the sequence of Fibonacci (that is a number of the homonymous succession formed by numbers where each one is the sum of the preceding two: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and so on).

The cross shaped flowers, formerly allocated this species in the Cruciferae family but as the paramount importance of the Brassica genus, presently is better to talk about Brassicaceae © Giuseppe Mazza

How can we explain these numbers?

It is easy to understand applying to the ramification of a plant the celebrated reasoning ascribed to Fibonacci for the growth of an ideal brood of rabbits.

The stem produces only one branch every year, in order not to weaken too much the plant.

Each new branch is able to ramify in its turn only after two years of its appearance. Let’s count the branches: First year: only the stem (tot. 1); second year; stem plus 1 branch (tot. 2); third year: the stem has again ramified, the first branch not yet (tot. 3); fourth year: the stem ramifies and also the first branch (tot. 5); the following year we shall have 8 ramifications and so on, following Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and so on.

Many plants display the Fibonacci numbers also in the phyllotaxis, that is in the arrangement of the leaves around the stem. In fact, the leaves are not arranged casually, but following a sort of spiral; every leaf tends to occupy a position such not to hide the underlying “companions”. Thanks to this order every leaf can receive the quantity of light sufficient to perform its own vital cycle regularly and the rainwater may rapidly reach, through the stem, the roots.

The cabbage in the art

Several varieties of cabbage appear in paintings, as still life, by various authors, but the best known paintings are those made by Arcimboldo (Vertumnus).

Finally the quotation of a famous poem cannot miss: “Una certa farfalletta, mossa un dì dall’appetito svolazzava in su la vetta di un bel cavolo fiorito …” (a certain small butterfly, moved one day by the appetite, fluttered on the top of a nice cabbage in flower)

(Clasio, pseudonym of Luigi Fiacchi 1754 -1825).

Synonyms

Brassica alba Boiss. (1839); Brassica alboglabra L.H.Bailey (1922); Brassica arborea Steud. (1821); Brassica bullata Pasq. (1867); Brassica campestris subsp. sylvestris (L.) Janch.; Brassica capitala DC. ex H.Lév. (1910); Brassica cauliflora Garsault (1764); Brassica caulorapa (DC.) Pasq. (1867); Brassica cephala DC. ex H.Lév. (1910); Brassica fimbriata Steud. (1840); Brassica gemmifera H.Lév. (1910); Brassica laciniata Steud. (1821); Brassica maritima Tardent (1841); Brassica millecapitata H.Lév. (1910); Brassica muscovita Steud. (1821); Brassica odorata Schrank ex Steud. (1821); Brassica peregrina Steud. (1821); Brassica quercifolia DC. ex H.Lév. (1910); Brassica rubra Steud. (1840); Brassica sabauda (L.) Lizg. (1965); Brassica sabellica Pers. (1806); Brassica subspontanea Lizg. (1965); Brassica suttoniana H.Lév. (1910); Brassica sylvestris (L.) Mill. (1768); Crucifera brassica E.H.L.Krause (1902); Napus oleracea (L.) K.F. Schimp. & Spenn. (1829); Raphanus brassica Crantz (1769).

→ For general notions about BRASSICACEAE please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the BRASSICACEAE family please click here.