- Defensive torpedoes are emerging as the best weapons for killing other torpedoes.

- Despite being relatively slow and ponderous, submarine-fired torpedoes are ridiculously difficult to intercept.

- The very attributes that make torpedoes slow also make them relentless killers.

In wartime, a new generation of anti-torpedo weapons could improve the survivability of surface warships. Today’s guided torpedoes are exceptionally difficult to defend against, despite their relatively slow speed, and for the past 70 years, navies worldwide have tried various countermeasures to confuse and distract incoming torpedoes to mixed results.

The result is typically sunken ships, but the emerging consensus is that nothing stops a torpedo like blasting it to bits ... with more torpedoes.

How do Torpedoes Work?

The torpedo is one of the most iconic weapons of modern warfare. Today’s torpedoes, unlike their ancestors welded to metal poles, are fired from submarines via torpedo tubes. Running off a single propeller, modern torpedoes are guided to the target by human control or an onboard package of sensors. Once at the target, they detonate their 600-plus-pound high-explosive warheads. One method of attack is to detonate on contact with the side of the hull. Another detonates the warhead directly under the keel, generating enough destructive force to snap smaller warships in half.

Heavyweight torpedoes can stalk their targets a number of ways. Most modern torpedoes have their own sonar capable of tracking a target by bouncing an acoustic echo off it and then measuring the distance to target. That method is known as active sonar. A more passive technique that doesn’t broadcast a telltale sound involves the torpedo listening for, and homing in on, the movement of enemy ships. Still other torpedoes home in on the foaming wakes ships leave behind as they ply their way through the oceans. Many trail control wires behind them that run all the way back to the firing submarine, allowing the sub crew to target individual ships, change targets, and more.

How to Stop an Incoming Torpedo

There are two fundamental ways to stop an incoming torpedo: countermeasures and physical destruction of the torpedo. Countermeasure devices don’t require the destruction of the torpedo, simply the foiling of its mission. A countermeasure defensive device might, for example, mask a warship’s noise or distract a torpedo into going off course. The U.S. Navy’s AN/SLQ-25E “NIXIE” countermeasure is a towed device designed to lure away a guided torpedo from its intended target, far enough that the torpedo’s warhead is detonated a safe distance away.

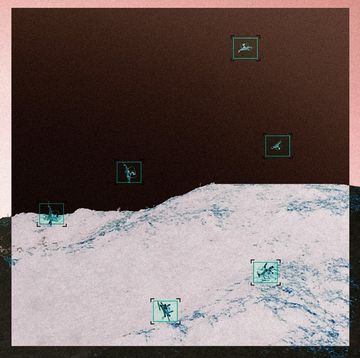

Countermeasures tend to be specific to the torpedo’s guidance system, so the best way to ensure a torpedo misses its target is to kill it. That’s not as simple as it sounds: It is much easier to intercept a cruise missile flying at 600 miles per hour than a torpedo swimming at 60 miles per hour. Torpedoes—while slower than cruise missiles by a factor of ten—are more difficult to detect, especially if they are simply listening for their target. Their underwater method of travel requires an interceptor that also travels underwater.

Will the U.S. Start Using Torpedoes in Anti-Torpedo Warfare?

Traditionally, the U.S. Navy’s first line of defense against torpedoes has been aggressive anti-submarine warfare—detecting, tracking, and destroying submarines before they can get close enough to launch torpedoes. Yet a sudden leap in submarine technology might make subs more difficult to detect, resulting in an increased likelihood of torpedo attacks. This leads us back to physical destruction of the torpedo. And anything that enters the water, moves under its own power, and takes action to intercept an enemy torpedo is … by definition ... another torpedo.

The modern torpedo has been around for about 120 years, so it’s ironic that it’s more difficult to stop than a guided missile. Is the torpedo the ultimate anti-torpedo weapon? If the intent is to destroy the torpedo instead of decoy or lure it away, it’s certainly looking that way. The U.S. Navy canceled its anti-torpedo/torpedo research in 2018, but as China’s submarine forces grow, we’re betting the service will sooner or later circle back to that research—much like a guided torpedo.

Kyle Mizokami is a writer on defense and security issues and has been at Popular Mechanics since 2015. If it involves explosions or projectiles, he's generally in favor of it. Kyle’s articles have appeared at The Daily Beast, U.S. Naval Institute News, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, Combat Aircraft Monthly, VICE News, and others. He lives in San Francisco.