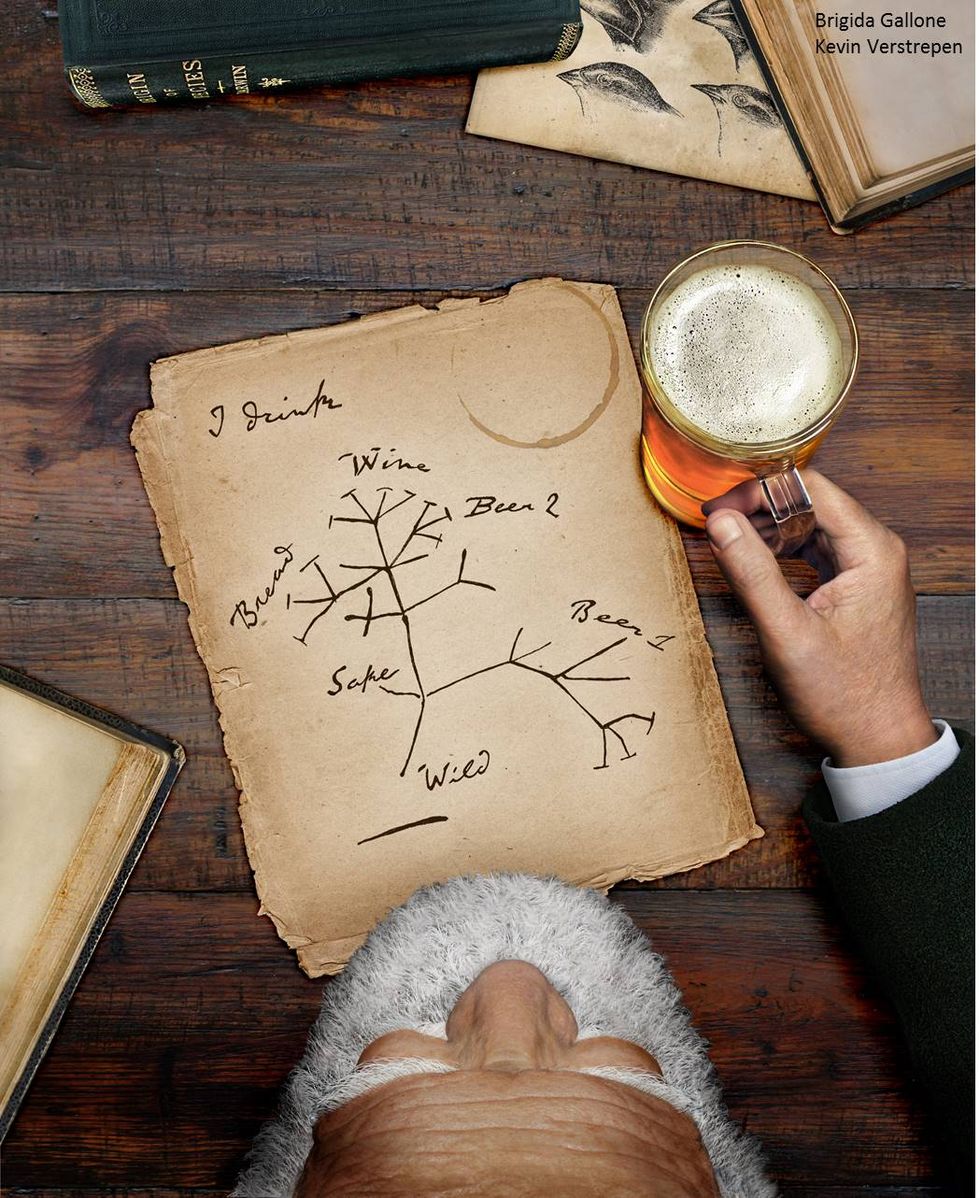

Beer just got its first genetic family tree.

From crisp lagers to hearty pale ales to cloudy hefeweizens, beer owes much of its stunning variety to the hundreds of strains of yeast that ferment it. Now a team of geneticists has created the first family tree of those yeasts, using samples collected from nearly a hundred breweries around the world.

The tree demystifies the historic spread of modern beermaking across Europe and America and outlines the relationship between yeasts used in different breweries—from Belgium's Duvel brewery to Sam Adams, Stone, and Sierra Nevada in the USA. One of the oddest takeaways from the family tree is the fact that modern brewing yeasts were domesticated in two separate lineages, and both pretty recently. The scientists published the family tree today in the journal Cell.

The genetics research was led by Kevin Verstrepen, a yeast biologist at the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology and the University of Leuven, in Belgium. Verstrepen and his colleagues genetically sequenced more than 150 yeasts for the project. Most are brewers yeasts, with some wine, sake, bread, and biofuel-making yeasts thrown in to boot. Verstrepen notes that today's family tree focuses heavily on the yeast behind ales, and that his team is currently working on the genetic linage of the yeasts behind crisper, lighter lagers.

Domesticated Microbes

To be sure, brewing beer is an activity as old as civilization itself. It reaches as far back as at least the early Sumerian civilization, five thousand years ago. But Verstrepen found that brewing yeasts were only truly domesticated sometime in the late 1500s or early 1600s. That's when yeasts were still unknown to humans—before Louis Pasteur discovered microbes for the first time. "It's pretty fascinating to think that we started domesticating these creatures before we even knew that they existed," Verstrepen says.

It was then, Verstrepen says, that brewing yeasts started to look genetically quite different from their feral cousins. In particular, beer yeasts lost the ability to sexually reproduce and gained genes that helped them chomp through a type of sugar called maltose that is abundant in the grainy slop prepared by brewers. "With this domestication, the yeasts started to look almost like a new species, much like how dogs don't look like wolves anymore," he says.

So why did this happen in the 1500s, and not earlier? "You have to understand, for most of human history beer making happened in homes and sporadically. Because it keeps for a long time, you can imagine making beer only once a month or so," Verstrepen says. That's important, because if you're making beer sporadically, your short-lived yeasts will have to survive in the wild for generations between batches. They'll interbreed and share genes with other wild yeasts and stay feral. This is one reason why wine yeasts—which are used just once per year—look almost identical to wild yeasts even today.

"But around the 1500's and 1600's in Europe, you start to see more commercial brewing, in towns and cities and monasteries," he says. "You have brewers continuously making beer, and practicing what's called 'backslopping', where you take sediment that forms at the end of the brewing process—which contains yeast—and inoculate your next batch with it." By this time, people had an intuitive understanding that leftover brewing waste somehow helped beer taste consistent. This is the period when brewing yeasts started to live in batches of beer for generations without returning to the wild.

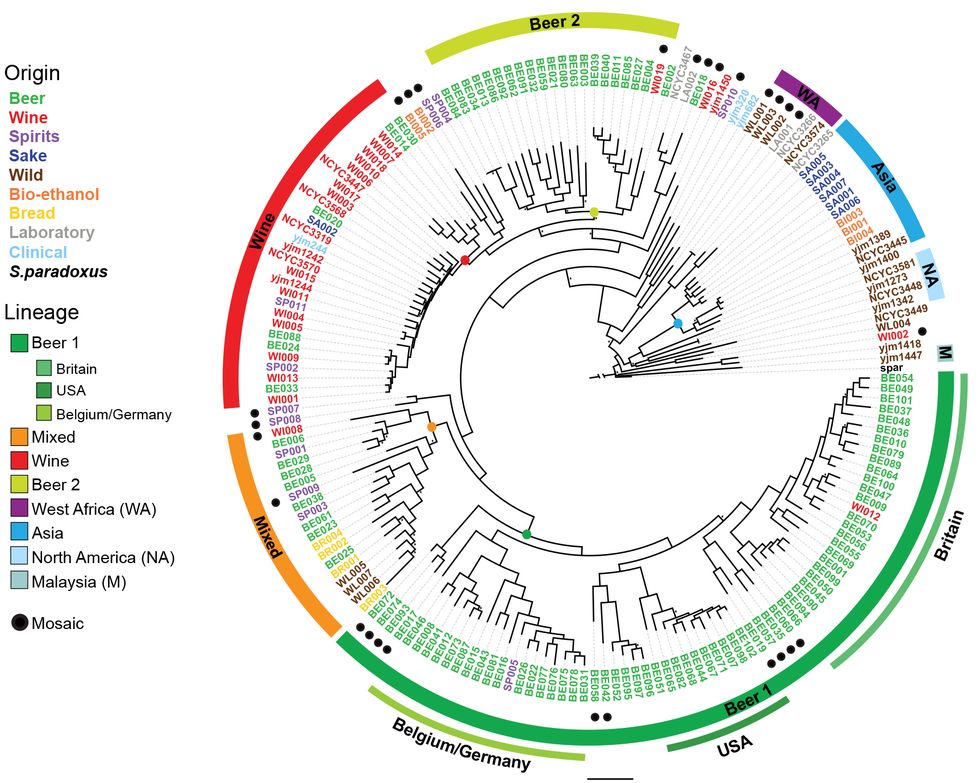

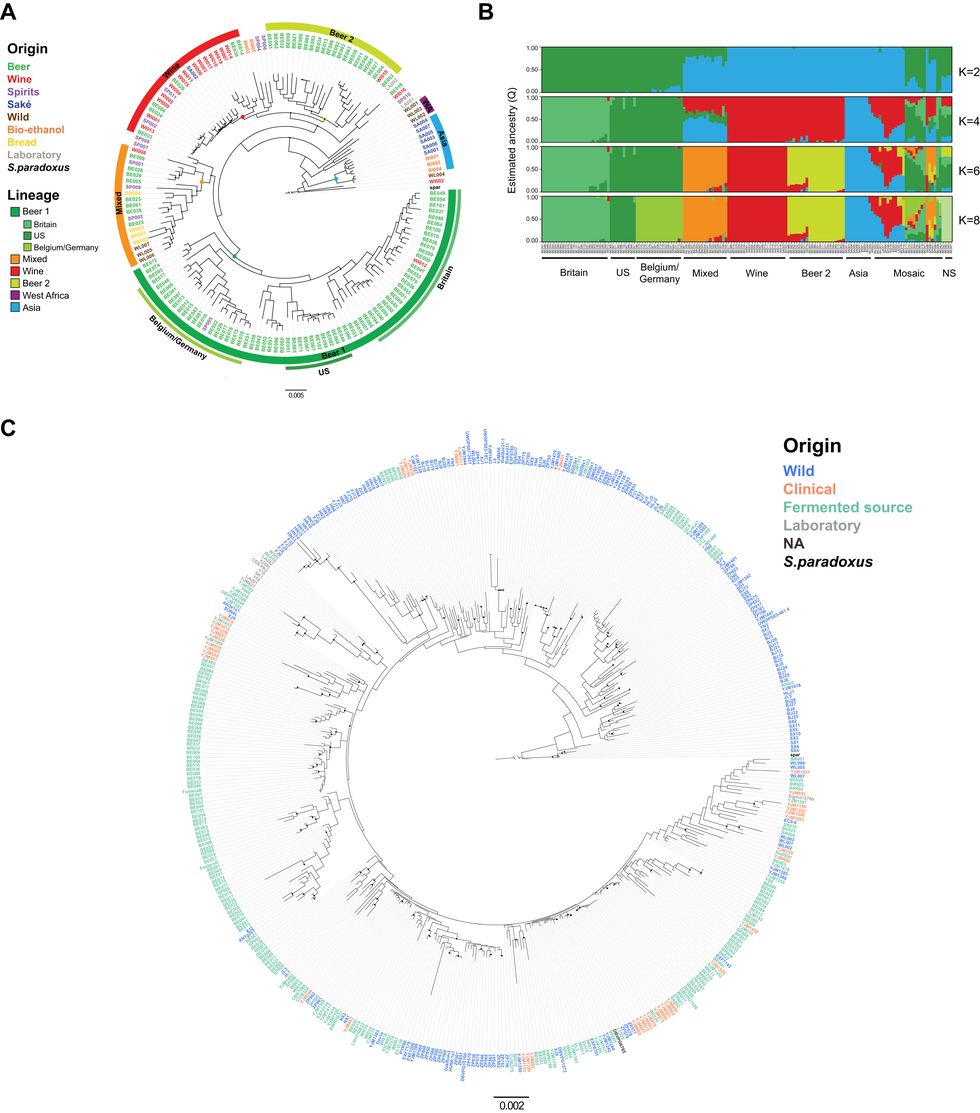

Yeast Family Tree

By comparing the genetic makeup of modern yeasts the world over, Verstrepen found that the first linage of domesticated brewing yeasts (called Beer 1) formed around this time, the turn of the 17th century. This linage of yeasts started in breweries around Germany and Belgium. As brewers shared tips, tools, and yeast sediment, those yeast spread to breweries in the U.K., and then branched off into American breweries. Most of the yeasts used in brewing today fall under this Beer 1 linage.

But half a century later, around roughly 1650, another linage of beer-making yeasts arose independently. This linage is called Beer 2, and generally speaking these yeasts make beers with higher alcohol content. Based on these microbes' genes, scientists can tell that they evolved from yeasts found in wineries. Because this new yeast was rapidly shared among brewers across the U.K., America, and Europe, Verstrepen says it's hard to place exactly where it first arose.

It's almost impossible to distinguish which of the two lineages a yeast comes from based on the flavor alone. That's because yeasts can create such a wild menagerie of flavors that the brewing differences between even two closely related yeasts can be vast.

Although Verstrepen's team collected yeasts used in famous breweries around the world, from Sam Adams to Duvel, in the new family tree "we deliberately obfuscated which yeast came from which specific brewery, to protect the brewers," he says. That's because many brewers—especially old, longstanding institutions—still "consider their yeasts something of a top-secret ingredient."