Edvard Munch, Norway’s national treasure and best-known artist, was one of the most innovative painters of his time. Over six decades spanning two centuries, he produced works that were technically daring and profoundly human, exploring themes of love, death, illness, and isolation.

Edvard Munch, The Dance of Life, 1925; photo: courtesy the Munch Museum, Oslo

1. He kept most of his own work for himself.

Edvard Munch, Munch Sitting in the Winter Studio, ca. 1938, © Munch Museum, Oslo

Munch was incredibly prolific, creating thousands of artworks over his six-decade career. And because he enjoyed widespread fame by the end of his life, he wasn’t compelled to sell the majority of his paintings and prints, but rather retained and lived with them. Upon his death in 1944, he bequeathed 1,150 paintings, 17,800 prints, 4,500 watercolors and drawings, and 13 sculptures, as well as numerous sketchbooks, letters, and manuscripts, to his native Oslo.

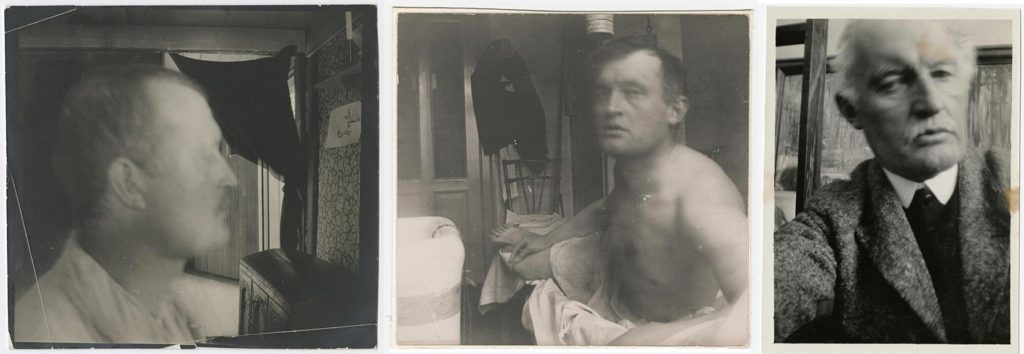

2. He was an enthusiastic selfie taker.

All photos by Edvard Munch; © Munch Museum, Oslo. From left to right: Edvard Munch in Profile, Indoors, 1904; Edvard Munch as Marat in the Bath at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic, 1908; Edvard Munch in Front of “The Death of Marat,” 1930.

Munch’s enormous talent was accompanied by an equally large ego. In addition to painting no fewer than seventy self-portraits in oil (and including himself in many of his other works), he was also a fervent selfie taker — more than a century before the advent of Instagram.

3. He most likely never had the Spanish flu.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919; National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design, Oslo

In Munch’s moving Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, you can almost hear the artist moaning with effort to keep himself upright in his chair. But recent research suggests that he never actually had the virus, which swept Europe from 1917 to 1920 and killed an estimated fifty million around the world. One theory is that he hoped the painting would arouse sympathy among the Norwegian public. In any case, the work explores a significant theme for Munch — illness and death as essential aspects of the human condition.

4. He frequently painted — and even stored some of his canvases — outdoors.

Edvard Munch, Munch in the Open Air Studio, ca. 1927; © Munch Museum, Oslo

Munch, like many of his contemporaries, frequently painted outdoors. He also subjected some of his paintings to the elements after they were completed, stacking canvases in roofless studios he had specially constructed at Ekely, his residence on the outskirts of Oslo. His reasons for doing this remain a topic of scholarly debate. Exposure to the elements left some of his works with brittle or cracking paint, stains, mold, and even traces of bird droppings.

5. His first solo exhibition in San Francisco was nearly 70 years ago.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894; © Munch Museum, Oslo

In 1951, San Francisco’s De Young Museum was one of several stops on a nationwide traveling exhibition of Munch’s work. A Los Angeles Times review at that time noted that Munch “painted vigorously for 64 of his 80 years,” and was effusive in its praise of one particular piece titled Puberty (a version of which is in SFMOMA’s current exhibition), noting, “If he had never painted anything but Puberty, the picture of a bewildered young girl, we should be in his debt.”

Opening on June 24 at SFMOMA, Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed is the global debut of a new exhibition featuring 44 of Edvard Munch’s intensely personal, groundbreaking artworks, and includes seven pieces never before shown in the United States. Tickets are on sale now.