The Seychelles: Really Away From It All

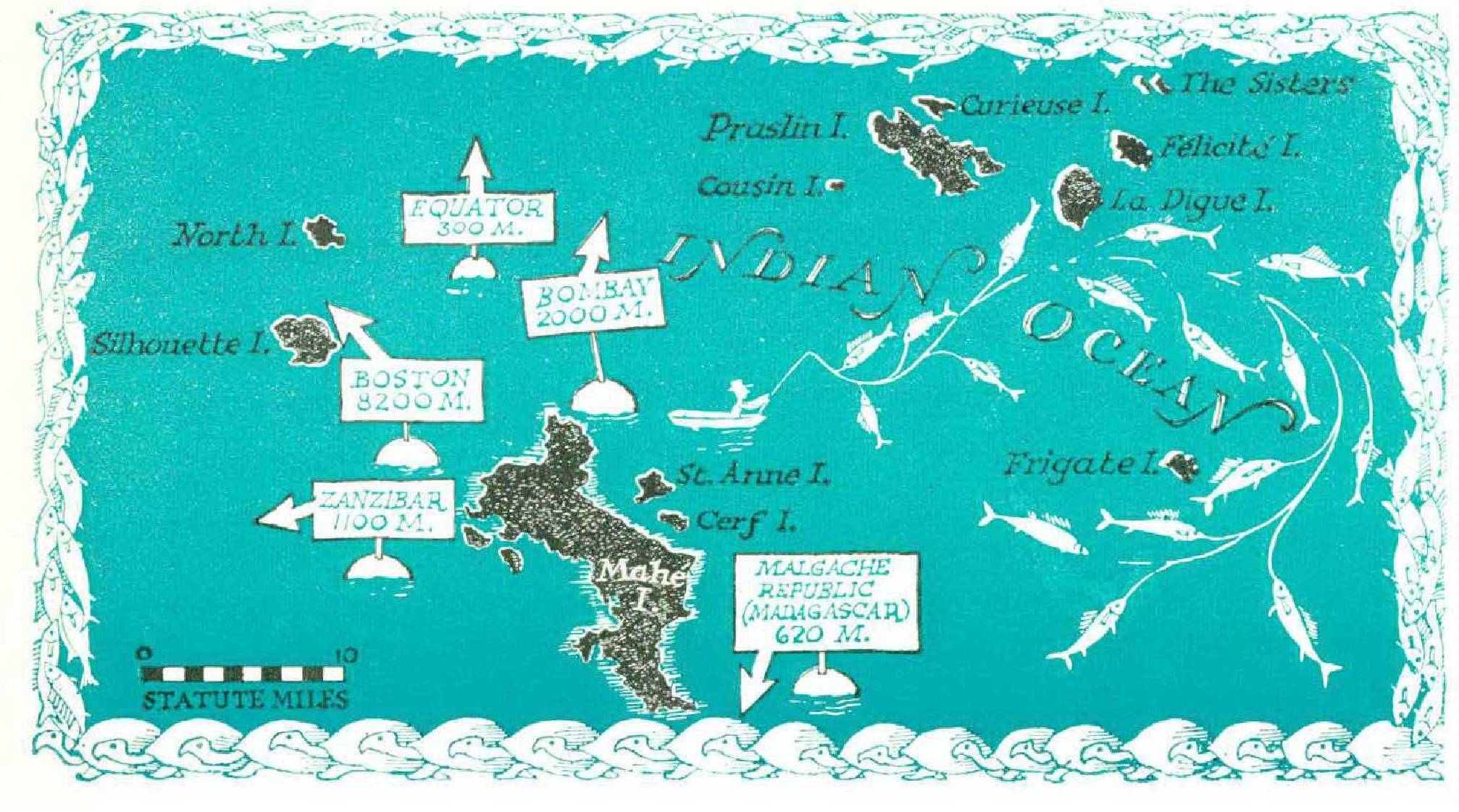

Only if your world map or navigator’s chart is a detailed one will you find clearly marked, at 4°40' south of the equator and at longitude 55°30', the Seychelle Islands. Some of these islands are made of granite, others of growing coral, a few of guano. There are ninetytwo in the chain — sixty are uninhabited — and they are strewn across the glittering ocean as if by some mischievous genie who gaily dipped his flying carpet down from Bombay on a scimitar-shaped spin to Zanzibar Island. Spread over 150,000 square miles of blue-black sea, they have brilliant white beaches and are totally isolated from the outside world. Most of them bear alluring names such as Silhouette, La Digue, Poivre, Curieuse, and Félicité. There is a town called Petit Paris, another named Zig Zag. The prominent twin peaks on the main island of Mahé (four miles wide and seventeen miles long, it is the granite home of a majestic shade tree called the takamaka) are daringly known as Les Mamelles to the predominately Roman Catholic locals, a proudly unique race of Creole-speaking, effervescing, and happy-go-lucky people known as Seychellois.

The Seychelles are a British crown colony. The governor is an able and scholarly aesthete who knows the Empire’s islands well. He was posted to both Zanzibar and Santa Lucia before coming to the Seychelles in 1962. His Excellency and Right Honorable the Earl of Oxford and Asquith, CMG, son of Sir Herbert Henry Asquith, the British Prime Minister at the beginning of World War I, tends his flock of 42,000 Seychellois and 1.5 million palm trees in haut monde fashion. There is plenty of time for him to collect freckled strombs, play tennis, and entertain visitors in the highceilinged gleaming white palatial government house. Inside, a small boy in a well-starched white tunic pumps the punkah from behind an embroidered screen, while linensuited guests take the noonday Pimm’s or pink gin, and the governor’s charming Rumanian-born wife, smoking a dainty cheroot, discusses philosophy.

There is no air service to the Seychelles because there are no landing strips. Rusty-hulled dowagers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company Limited only occasionally, and then reluctantly, anchor off Mahé’s Sainte Anne Channel (for there is no dock either). There the captain picks up copra and the royal mail from Victoria, the capital, while depositing by small boat the odd visitor, who has probably spent most of the voyage (from either Bombay or Mombasa) in cabin and on Dramamine dispensed by the garlicky Goan medical officer. Until 1959 there was no bank on the islands, and trial by jury was “discovered” three years ago.

The world only seems to have passed up, and by, the Seychelles. Actually, they have a most prominent and adventurous place in both legend and history. Seychelle coves provided sanctuaries for the pirates who during the eighteenth century were working the lucrative East India routes, where the haul was usually chained slaves, Maria Theresa talers, and church plate. France claimed the islands in 1756 when it heard the British were also looking them over. But by the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Napoleon ceded them to King George III. During the 1870s, the African explorer Henry Morton Stanley kept a house, called Livingstone Cottage, on Mahé. However, it was not until the arrival of General “Chinese” Gordon in 1881 that the islands achieved a niche in history.

Upon setting foot on the island of Praslin (accompanied by his trusted guide, Adam, it should be noted), the hero of the Sudan campaign proclaimed: “It’s the original Garden of Eden.” Gordon was positive of this because he located the mysterious coco-de-mer palms growing in the island’s Vallée de Mai, lush, steamy, and inhabited by black parrots. He was sure the palm bore the biblical fruit of knowledge. Even today the palm grows nowhere else in the world. It was so named by sailors of old who thought it grew under the sea because the nuts were only found floating on the ocean. Indians and Chinese still pay enormous prices for the nut’s opaque jelly, considered a better aphrodisiac than even the famous Seychelles sea slug, or a ground rhino horn from East Africa.

The people of the Seychelles are truly an exotic breed. Their saga is an enchanting one, if uncertain historically. What is clear is that the people are a most recherché ethnical rainbow. They range in color, complexion, and design from woollyhaired cobalt blacks of Nubian beauty, through sepia-skinned Hamitic handsomeness, to blond-haired and blue-eyed Teutonic perfection. They speak the singsong Creole patois, which is warmly lilting though almost incomprehensible. The race, for it is now surely that, came about in the 1790s from a potpourri consisting of 487 African slaves, 63 French farmers, 32 Coloreds, 3 soldiers of the garrison, and one retired pirate.

Since then the bloodline has been enhanced by dashes of Chinese traders from Canton, Indian merchants from Madras and Sikh country, an occasional passing Malayan wanderer, and visiting sailors from a dozen European nations and ports. During the nineteenth-century reign of the clipper ship, dozens of whalers out of New England harbors often called on the islands for fresh water, turtle meat, and coconuts. Their visits resulted in the dozens of redheaded and freckle-faced Seychellois who today stroll the winding streets speaking Creole without the slightest trace of a New England accent.

Most Seychellois are positive that the Dauphin, heir to the throne of France if Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had not been guillotined, lived and died on Mahé after siring, under the name Pierre Poiret, until he was well into his seventies. Just how deeply the Seychellois believe this was explained to me one evening by an English seashell fancier, Tom Jones, who owns the local novelty shop, where the specialty is a handsome walking stick made from the bleached vertebrae of a killer shark. He insisted that a prominent Seychellois member of the Legislative Council recently rejected an invitation from the honorary French consul to attend the traditional July 14 Bastille Day celebration at the Pirates Arms Hotel.

“Je refuse!” he proclaimed. “You French killed my great-great-greatgreat grandfather.”The descendants of Poiret are numerous and are usually named either Louis or Marie.

In recent years retired British civil servants, about one hundred strong and from posts around the world, have added a new group to the islanders.

It is quite understandable to be told by the locals how completely content they are with things just as they are. They love their rickety houses on pencil-thin stilts (in case the tide comes in high). They feel completely protected with a flock of geese as home guards. Their dogs and cats thrive on the plentiful coconuts. Berry-loving myna birds do most of the sowing of the main crop, cinnamon, through their droppings as they wing around the islands. The waters are alive with tasty fish — the bourgeois, becuna (barracuda), and all sorts of mackerel. After sleeping, fishing is the national pastime of the Seychellois. I once asked a fisherman the hour. He shrugged. “All I know is it must be in the afternoon, for I have already taken lunch, Monsieur,” he explained, and went back to sleep under his favorite takamaka tree.

The clock chimes in Victoria strike twice — on the hour and one minute later, for those who were not paying attention.

The British have been kind in ruling this paradise. The government subsidizes the staple of rice, doles out free tea, and maintains palm-toddy shops throughout the islands.

This year the local economy got an American-style shot in the arm. The U.S. government, along with the Philco Corporation, built a satellitetracking station on Mahé. It is called '‘Le Golf ball” by the locals because of its resemblance to one. The hundred civilian technicians are good spenders in the local pubs, like Sharkey Clarke’s place, when they come down from their hilltop barracks. Several laborers have found the Yankee dollar more acceptable around the island than the traditional rupee (4.5 rupees to $1.00). A result has been several attempts by local forgers to crank out U.S. dollars on a “borrowed” U.S. Air Force mimeograph machine.

Despite all the inaccessibility, the hope and prayer of every Seychellois is tourism. Everyone is gossiping about a landing strip being built someday, even though a RAF survey team recently reckoned there was not enough flat land on Mahé to launch a balloon. The crafty Seychellois merchants and plantation owners are now plotting blackmail.

“Let’s tell the Americans that if they want Le Golfball to stay, they must build an airport” is the strategy line making the rounds on the sturdy interisland steamer, the Lady Esme, where all passengers are supplied with brightly colored plastic bowls in case of trial de mer.

Mahé itself already has six hotels, with cottages for two costing $5.00 per day, meals included. They offer unexpected hot water from the cold faucet, stream-washed laundry brought to you on a tray, sunsets and beaches that make Jamaica’s Ocho Rios and the French Riviera look like Coney Island in a perpetual foggy drizzle.

The Seychelles represent the last Shangri-La islands that are likely to remain so for decades to come. News of the outside world barely trickles in via a thin government handout; the usual topics are the rugby scores from Great Britain, what new films have arrived, and ship schedules. Radio Seychelles is on two hours daily and can be picked up only on certain streets of the city. “Bon,” say most Seychellois to all this.

The people are more concerned with letting outsiders know that the big-game fishing is considered better here than off Baja California or the Peruvian coast, with swordfish running to twenty-five feet (according to the tourist board). The goggling is exciting out on the coral reefs near Anonyme Island. For clothing, all one really needs is a beach towel, which can be used for both drying and covering, and a pair of sandals.

The biggest attraction still is the isolation, which the locals are in no hurry to change, although they would like that airport. Politically, the islanders wish to remain a British dependency. It is an annual occasion for the leading political party, the Seychelles Taxpayers’ Association, to cable Queen Elizabeth about its undying loyalty and utter horror at the mere thought of freedom. There are two ways to make Seychellois mad. One is to close down a toddy shop; the other is even to hint that maybe the islands should link up with one of the newly independent African countries to the west. To most Seychellois, Africans are just not their kind of people.

Though some outsiders have made visits to the islands to attempt stirring up anticolonialism, a government security officer, lounging in his starched white shorts, yawned as he explained: “The Seychellois suffer from a congenital disease — they can’t keep secrets.” And since the policeman on the beat is also the mailman, any overseas literature more radical than the Times of London never makes it to the mailbox.

“We’re fifty years behind the times,” said graying Henri Daubon, a leathery sixty-three-year-old French plantation owner from Praslin. He beamed with Seychellois pride, then pointed out a bright blue-feathered bird, called pigeon hollandais, that winged over my patio at the Hotel des Seychelles, cable address IDYLLIC.