Can This Man Save U.S. Soccer?

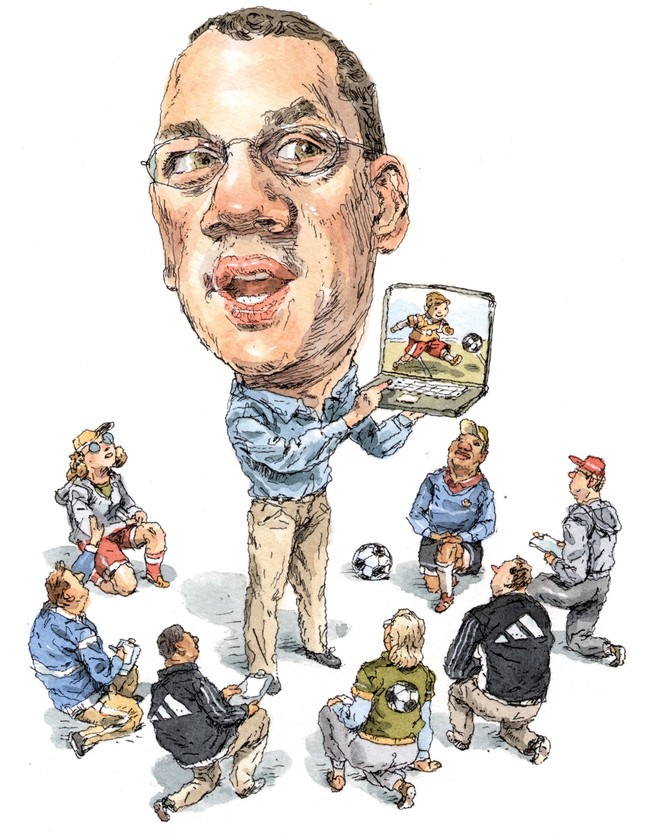

How one teacher is attempting to train a generation of globally competitive players—starting with their coaches.

Americans perform about as unimpressively in soccer as they do in education. In both cases, the United States has suffered from a lack of focus and rigor, despite significant investments. More than 4 million kids are now registered in American youth-soccer leagues—more than in any other country—and yet the U.S. has never produced a Lionel Messi or a Cristiano Ronaldo. The men’s national team still struggles to compete internationally. The women’s team just won the World Cup, a shining accomplishment, but its players owe their success more to speed and athleticism than to technique; with powerhouses like Germany and France finally getting serious about girls’ sports, the American women will likely face stiffer competition in the years ahead.

American soccer officials are therefore humble in a way that other sports executives are not. “We need to improve, or in a few years, all those people we’ve gotten to pay attention [to soccer] will drift away,” says Neil Buethe, the head of communications for the U.S. Soccer Federation, the sport’s governing body in the United States. “A win only happens if our players get better, and our players only get better if the coaches get better.”

This thinking has led U.S. Soccer officials to an unconventional idea: that a teaching expert they first read about in The New York Times Magazine—a man with no professional soccer expertise—might help them advance the sport.

Among teachers, Doug Lemov is a sort of celebrity. He’s spent years studying great educators, creating a taxonomy of techniques they use to manage common challenges (like defiant kids or tired kids or kids who need a lot of time to learn something that other kids learn quickly). Each year, he trains thousands of teachers around the world to use these tactics. He’s also written a popular book called Teach Like a Champion and co-founded a chain of public charter schools in the Northeast.

When U.S. Soccer first reached out to Lemov, in 2010, the organization was already in the midst of a wholesale reformation. Four years earlier, soccer executives had toured the world, studying what other countries did differently. They had learned, among other things, that kids in other nations spent less time playing soccer games than did their American counterparts, and more time practicing. In response, the federation created its own youth league, called the U.S. Soccer Development Academy, modeled after international best practices. Top youth-soccer clubs could apply to join, if their coaches agreed to get licensed and follow a new model for training. The academy now comprises 152 soccer clubs across the U.S., which have produced more than 180 professional players.

Still, officials felt that more could be done. “For 20 years, we had focused almost exclusively on closing our global gap in the technical and tactical components of the game,” says Dave Chesler, U.S. Soccer’s director of coaching development. “In doing this, perhaps we had lost perspective on the quality of our delivery—a k a the essential mechanics of teaching. ” Chesler, who had himself spent 15 years as a high-school chemistry and physics teacher before becoming a full-time soccer coach, realized after reading about Lemov in The Times Magazine that he had never transferred some of his own best teaching techniques to the field. He made immediate modifications to his coaching—for example, slowing down practices and focusing more on watching the players, making sure each one demonstrated every step in a drill before moving on—and he sent copies of Lemov’s book to his national staff. And then he asked Lemov for help.

Lemov was thrilled to hear from U.S. Soccer. But he was nervous, too, like a fanboy unexpectedly pulled up onstage. He understood teaching, and it so happened that he loved soccer, but he didn’t know whether his work would translate for coaches—or whether they would listen.

Lemov started playing soccer when he was about 7 and still has the build of an athlete, tall and broad-shouldered. He was never a star, but he managed to win a spot on the Hamilton College soccer team through constant, solitary practice. It was a highly inefficient process, he now realizes, akin to learning French by sitting in a room, alone, with a French-English dictionary. Like many American soccer players, he was largely coached by people who lacked expert knowledge of the game. Once, at a friend’s house during his senior year in college, he found a dusty videotape on defensive tactics, which demonstrated how best to bend your knees and angle your body when confronting an opponent. Lemov felt blindsided. The advice made sense, but he’d played defense for 14 years, and he’d never heard it. “All my life I’d been yelled at to ‘defend,’ ” he says, “but no one had ever told me how to do it.”

These days, he spends more time watching his own children on the soccer field than he does playing. He has seen them coached well, which fills him with gratitude. But he’s also seen them coached poorly. One of his son’s coaches sometimes yelled negative, perplexing things. “He would speak in these riddles: ‘Where should you be?’ ” Not knowing the answer, the boy would stand still, afraid of making a mistake. Lemov found the scene heartbreaking and also familiar; he’d had the same feeling many times before, standing in the back of classrooms, watching well-intentioned teachers flounder.

This coach, Lemov knew, was generously donating his time and doing what he thought was right. But coaches, like teachers, need practical training and meaningful feedback to do well. Teachers rarely get that support; coaches almost never do. And so, with Chesler’s help, Lemov set about identifying specific tactics coaches could learn from great teachers—establishing rituals so drills start faster, say, or helping players get comfortable making mistakes in practice. So far, Lemov has trained about 200 coach educators, who in turn teach rank-and-file coaches around the country. He and U.S. Soccer have also created an online lesson that will be required viewing for tens of thousands of volunteer coaches seeking the federation’s entry-level license.

This training will not look familiar to American adults who learned to play soccer at more traditional practices—where they ran laps to warm up and then waited in lines to take practice shots on goal. Little kids don’t need highly structured warm-ups, according to U.S. Soccer; they arrive ready to move. And kids of all ages should be touching a ball as often as possible, without wasting any time waiting around. Throughout practice, players need productive, quick feedback in a culture that encourages them to take risks and make mistakes.

Soccer, it’s sometimes said, is a player’s game. The 22 people knocking a ball around a big field are bound by few rules. Predictable patterns rarely occur. As a result, coaches can’t succeed by designing plays and ordering players to execute them, as they can in, say, football. Players have to make judgment calls in the moment, on their own.

This means that rote skills, while essential, are not in themselves adequate. “The thing that makes elite players is decision making,” Lemov told me. “They need to integrate not just how to do something but whether, when, and why.” He sees parallels to the difficulty many American students have solving problems independently. “If you give [American] kids a math problem and tell them how to solve it,” he said, “they can usually do it. But if you give them a problem and it’s not clear how to solve it, they struggle.”

Jürgen Klinsmann, a former soccer star in Germany who now coaches the U.S. men’s team, has remarked that it’s hard to get Americans to see that a soccer coach cannot be “the decision maker on the field,” but should instead be a guide. “This is a very different approach,” he told USA Today. “I tell them, ‘No, you’re not making the decision. The decision is made by the kid on the field.’ ” Outside the U.S., most soccer players learn to play independently very early on; from the day they can walk, they are kicking a ball every free moment. In the process, they gain both physical and mental dexterity. “That’s not always [been] the case here,” says Jared Micklos, the Development Academy’s director. “We didn’t have a lot of unstructured play where kids could develop creativity. It was a lot of tournaments and pressure and sideline parents and trophies.” In the absence of back-alley pickup games, soccer players in the United States must develop their skills in supervised practices. That’s why high-quality coaching is so essential to nurturing world-class American players. “If we want better players, we need better coaches,” Micklos told me. “In order to get better coaches, we gotta coach them.”

On the first truly cold night of the fall, a group of coaches from all over Virginia gathered inside a rec center in Arlington to learn from Lemov. The scene was noticeably different from his teacher trainings, where audiences tend to be disproportionately female and to clap a lot. The assembled coaches, most of them men, most of them wearing Adidas jackets, were a little less affirming, a bit more jocular. (One had written “God” on his name tag.) Still, Lemov addressed them with the same gentle intensity that he uses with teachers. “I appreciate the work that you do,” he said, taking pains to make eye contact with each coach through his small, wire-frame glasses.

As he does with teachers, Lemov asked the coaches to write up sample lesson plans describing their practice drills, predicting errors that players would be likely to make along the way (accidentally fouling another player, say, or letting the ball drift too far from their feet), and describing the ways they would try to correct these mistakes. Next he played a short video of a girls’ soccer practice in which players fumbled through a poorly explained drill. (The girls had been asked to do too many things at once, a classic mistake.) He called on the coaches by name, just as he trains teachers to do, asking small questions to check that they understood what he was teaching. “What did you notice, T.J.?” “Why didn’t the girls understand, Ryan?” He puts the question before the name so that everyone feels compelled to contemplate an answer. Lemov takes the mechanics of teaching deadly seriously, in hopes that his pupils will too. Before the lesson ended, he’d called on everyone, including “God.”

Finally, the coaches headed outside to observe one of their own, T. J. White, leading a practice. White explained the first drill to a group of 20 not-quite-adolescent boys, and soon the frigid air filled with shouts. “Over here!” “What are you doing?” “Yes!” “Back corner!” For an hour, they played happily, paying no attention to the scrum of adults watching from the sideline.

At the center of the group stood Lemov, who was busy taking notes. He timed how long White took to explain each new activity. Could he have been quicker, so that the kids stayed engaged and spent more time playing? Lemov counted the number of quality touches on the ball per minute. Were all the kids getting lots of chances to play? He watched to see whether White had designed the drills in such a way that he could easily look at all the kids at once and assess whether they had mastered a given skill before moving on.

As White ran his practice, he called on players to check for understanding, just as Lemov had. He gave the kids breaks, but they were short, so as to keep things moving. His voice remained calm and positive throughout. When the practice ended, White jogged over to the other coaches. “You’re a little bit nervous in that situation,” he told me later. “I’ve never been given feedback in front of 18 people.”

Lemov described what he’d seen, using words rarely strung together on a soccer field: “Competitive, joyful, and intelligent.” White nodded, looking worried. Lemov asked him how he thought the practice had gone and listened carefully. Finally, he made a suggestion so delicately worded that it almost seemed like an afterthought: “I found myself wondering what would happen,” he said, “if you did just one drill instead of three and layered on challenges within that one drill.” White agreed that might be worth trying. Then Lemov closed with the ultimate compliment: “I’d let my son play for you.” With that, White smiled for the first time all night, and the two men shook hands.