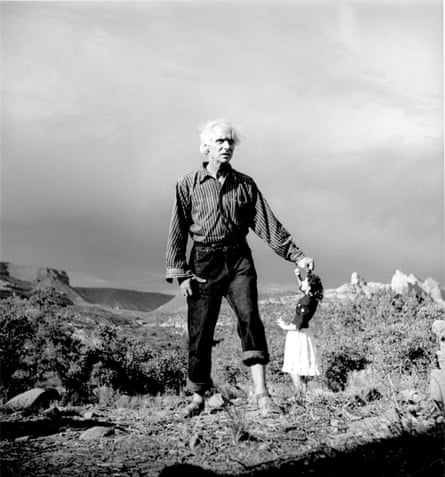

In 1946, Lee Miller visited Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst in Sedona, Arizona, and took 400 photographs of the desert and her hosts. Her most famous image enlarges Ernst into a giant, striding forwards out of the picture towards us, his expression part inspired, part demonic. Tanning gazes up at him from just behind, caught in profile with her white skirt billowing, shrunk into a compact Alice in Wonderland. Is the photograph observing the power dynamics of the men and women of surrealism, with which Miller was all too familiar? Or is it more concerned with offering us a surrealist desert fairytale?

It was appropriate to depict Tanning as Alice. There is an Alice-like quality to her self-portrait in Birthday, the picture that established her as a painter and brought about the relationship with Ernst when he arrived at her New York studio in 1942, dispatched by his then wife Peggy Guggenheim to prospect for work to include in an exhibition of female artists. Tanning showed him her painting and asked what she should call it; Ernst named it Birthday and moved in with her a week later. The painting depicts a bare-breasted young woman gazing blankly out with a kind of all‑knowing innocence. Wearing an open Elizabethan-style dress with seaweed hanging from her skirt, Tanning resembles Alice but also resembles the Gryphon, the upright winged griffin Alice encounters on her travels. In the background are the endlessly opening doors that would populate Tanning’s paintings over the next decades.

Ernst was another artist fascinated by Lewis Carroll’s story. In 1941 he portrayed her as a naked grown-up woman hidden within a giant rocky growth. Tanning’s and Ernst’s paintings speak easily to each other, though Ernst’s Alice is modelled on Leonora Carrington, his lover before Guggenheim. He liked younger women he could see as Alice-like figures – Tanning was born 19 years after Ernst, in 1910, and Carrington in 1917. But though younger, these were grown-up women. What of the more dangerously pubescent incarnation of Alice? It was left to Tanning herself to bring her into being in paint.

For Tanning, the move to Arizona in 1946 seems to have enabled a return to the erotic fantasies of her own adolescence, trapped among Lutherans in Galesburg, Illinois. During the decade after the war, she amassed an extraordinary body of paintings depicting girlhood as a time of dangerous appetites and uncanny erotic power. Now these paintings have been collected for a major retrospective of Tanning’s work, which is about to open at Tate Modern. They are pictures that Miller would have seen in Tanning’s Arizona studio, so perhaps what Miller was doing in her photograph was to imagine Tanning as the subject of one of her own paintings. Most famous is the 1943 Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, which portrays two girls in the door-lined corridor of a hotel. One leans back, eyes shut, in a dreamy reverie, her blond hair lining her back and her bare stomach pushed forward, suggesting the body of an older woman. The other stands upright, her hair flying above her head with a determined energy that gives the picture its charge. On the floor there is a giant sunflower, blown in from Arizona, its petals lining the staircase. At the edge of the picture, one of the doors opens into what could be a sunlit desert or a burning inferno. If we are witnessing the girls at the point of becoming, then it’s the moment before an explosion and there are violent, unseen forces at play.

In his 1945 meditation Arcanum 17 André Breton celebrated the femme-enfant, the pubescent girl who “sends fissures through the best organised systems because nothing has been able to subdue or encompass her”. He might have been thinking of the determined figures in Tanning’s 1942 Children’s Games, ripping off the wallpaper in a shadowy corridor to reveal fleshy protrusions beneath. In her autobiography, Tanning wrote later that during her adolescence in Galesburg “nothing happened but the wallpaper”. Reimagined 20 years later, the wallpaper itself becomes a potent, living force.

It’s this feeling, that the fantasies of girlhood are strewn before us on the canvas, that gives these paintings their power, and the feeling is not without its ethical complications. Was Tanning complicit in the aspects of surrealism that nowadays might be seen as morally questionable, even paedophilic? Yes, she probably was. Certainly The Guest Room (1950-2) makes difficult viewing when we know that the model for the naked pubescent girl who scowls at us from the open door was reluctant to pose nude for the picture, and that it was only after the sittings that Tanning painted her naked breasts, imagining them into being. But then this is hardly meant to be a morally straightforward piece. Behind the door the girl is shadowed by a blindfolded doppelganger; at the back of the room the figure of death approaches; in the bed another girl clasps a sinister amputated doll. The painting is undoubtedly erotic. It’s swathed in the shimmering fabric that drapes its way across a lot of Tanning’s pictures at this time, suggesting a kind of tactile ease at odds with the subject matter. But this is a dangerous eros, where a young girl’s fantasies can easily render her vulnerable, at the will of a more malevolent desire.

Tanning made this desire explicit in a story she wrote at this time called “Abyss”, published in 1949 and included in manuscript in the show. Here Albert, a house guest at a mansion in the desert, encounters his host’s seven-year-old daughter in her rooms at the top of the house. The rooms have the sumptuous, treasure-trove feel of a Tanning painting, filled to bursting with “outlandish furniture and bricabrac”, strewn with heaps of dusty birds’ wings and at once “scalded” and “purified” by the light of a gigantic chandelier. Summoned by the child, “her bearing calm and imperious”, he is invited to sit down. When he refuses, she instructs him calmly to eat her dinner. In return, she will show him her memory box. Caught in a kind of trance, Albert sits at her little table and eats her food. At the end he looks at her: “His gaze devoured the little red mouth, the throat, the hair, the white dress, as his mouth had devoured the plateful of food.” Then he looks through her treasures, which turn out to be real eyes given to her by a friendly lion. Albert declares loyalty and love to the girl, scalded and purified in his turn.

It’s an enthralling story, and its strengths illuminate the strengths of the paintings: the way that curiosity about the inner life combines with confidence that the visual can be enough. The two-dimensional world of painterly surface, the visual depiction of a glittering eyeball in a messily sumptuous room surrounded by a frightening desert, are a story in themselves and don’t require psychological explanation. Yet the people who inhabit them are living figures, more so than in the work of most other surrealists. Tanning’s literary characters are more alive than those of Breton’s Nadja (his 1928 novel about following a young woman around Paris); the girls in her paintings have a greater feeling of bodily life than those in Ernst’s or Carrington’s.

The Tate show’s curator Alyce Mahon makes a compelling case for late surrealism in the catalogue, reminding us that it was a movement that continued to flourish and to mutate after the second world war. Tanning herself had experienced the beginning of the war first hand: she was holidaying in France when it broke out and made her way across Europe. For Tanning and Ernst, the war provided a backdrop for the realisation that surrealism had been right in its diagnosis of the blastedness of contemporary culture, and the death-dealing nature of conventional morality and institutional life. Tanning emerges convincingly here as a late surrealist who saw how much further surrealism could still be taken, finding in the desert landscape of Arizona a rich setting to juxtapose desire and violence.

Then in 1955, her style changed, becoming more gestural and abstract. In 1949, Tanning and Ernst started to spend more time in Paris, eventually moving there in the 50s. In Paris it was hard to ignore abstract expressionism and away from the desert she had greater freedom to reinvent her style and palette. In her autobiography she wrote that “my canvases literally splintered”. The pictures grew, and the brush strokes became larger and messier. These are more nebulous images but they are still populated by human bodies, whose limbs and torsos stretch across the canvas. In the 1980s some of the girls of the earlier paintings seem to reappear in new guises. There are the winding figures in her Daughters (1983), their muscles caught mid-motion in the violence of becoming. Her yellow Door 84 from 1984 feels like a De Kooning with two of Tanning’s girls thrown on to it. One splays her legs suggestively, the other traverses the picture as though mid-flight. Both are bounded by the wooden door that she attached to the canvas, giving the doors of her earlier work a kind of stubborn actuality that takes its language, playfully, from the idiom of her new contemporaries, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

During the 1970s and 80s Tanning was travelling artistically in two directions at once. At the same time as she was making these abstract paintings, she was returning to surrealism in the soft sculptures she started to sew in 1969. Listening to a performance of Stockhausen’s Hymnen at the Maison de la Radio in Paris, she found that spinning among the unearthly sounds “were the earthy, even organic shapes that I would make, had to make, out of cloth and wool”, blending the abstract and the everyday as in Stockhausen’s sound world (his piece includes cheering crowds and quacking ducks). She visited flea markets and went through her own wardrobe and found a lot of tweed and stuffing. Using table tennis balls for the bones on the spine, she created a series of human figures. Her Nue Couchée (1969) is like a more intimate version of a Henry Moore sculpture, with an exaggeratedly curved back wrapping around lengthily twined limbs.

The high point of this work is Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot, an installation of sculpted figures made in 1970-3 and included as its own room in the Tate exhibition. Here is once again the wallpaper of Tanning’s childhood, ripped open as in Children’s Games. Two bulging decapitated nudes clamber out of it, one with a foot just poised to emerge. On the floor there are a series of tweedy bodies caught in embraces with items of furniture. One lies back on a table, stretched in sensual languor. Another burrows into a chair with an intentness that easily evokes the feeling of a body homed by touch. Tanning’s joy in making these is evident. She admitted to finding “the brutal slashing of fabrics an incomparable pleasure in itself”. There’s such certainty in the shapes and their relation to each other, and yet also a literal throwaway quality: she made these objects knowing that they’d decay. They are now extremely fragile and this may be the last time they can all be shown.

Tanning died in 2012 aged 101. Her final decade was remarkably productive. She published two volumes of poetry and a novel, Chasm, which reworked the material from “Abyss” (and which Virago is now reissuing). Her late flower paintings are represented in the Tate by the delicately lovely Crepuscula glacialis (1997), which shows an ethereal female body floating behind a series of unfolding petals. This has something in common with Georgia O’Keeffe’s work, but the eroticism here is more diffuse, evoking less the physicality of sex than a more dreamy sensuousness.

In Tanning’s Chasm the original story becomes the centre of a remarkably suspenseful tale of sex and violence in the desert. Looking back on the landscape half a century later, Tanning expanded the descriptions in loving detail. “The desert is full to bursting,” the heroine Destina’s great-grandmother says, “the sand talks to you, but its words don’t rhyme.” The climax of the story comes when Albert and his fiancee Nadine confront Destina’s friend the lion, who comes to symbolise nature in its raw power: “a cruel, laughing force extravagantly beyond her notions and, above all, indifferent to her existence”. This results in a series of deaths, inside and outside the house, which bring the feeling that Tanning has written away surrealism, destroyed it in a bloodbath and then called in the police to clear away the remains. At the end, Destina is left with only her ordinary girlhood, brutally removed from the fantasy world of her past. Now when she visits the desert she finds “a piece of dream broken off the rock of herself”. The nonagenarian Tanning seems here to be confronting her earlier paintings.

That late surrealism still needs rescuing by curators and critics is perhaps not a sign of its defeat but of the breadth and pervasiveness of its triumph. Could we have Pablo Picasso or Jackson Pollock without surrealism? What about David Lynch, JG Ballard or Angela Carter? As an influence, it’s easy to give her a crucial place in the canon of feminist art. Louise Bourgeois was born just a year later than Tanning but only started to sew after Tanning had exhibited her first sculptures; think too of the role of sewing in the work of Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas, whose Nud Cycladic (2010) presents a series of twisted forms made using stuffed tights. These forms have become a convention of contemporary sculpture – Tanning was there first.

Had she followed the example of Destina’s great-grandmother in Chasm and lived to see yet another generation, what would Tanning have made of the world now? Certainly her complicated, energetically writhing vision of female sexuality seems still to have much to communicate, if only because it remains so determinedly morally neutral. She doesn’t tell us what to think, or even tell us what she thinks, reminding us of the element of desire that can’t be explained. At once alluring and disturbing, this is desire as an erotic force. It’s perhaps best caught in the shimmering silks that tantalise the femme-enfants of the early paintings, or the rough yet tactile tweed-clad limbs given languorous, lustful life in room 202.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion