"Where are you?" asks Colin Thubron in his 10th travel book, as he gulps thin Tibetan air. In the other nine volumes, the inner journey hovers between the lines as our man bushwhacks through the lost heart of Asia, bounces along the silk road in the back of a superannuated Moskvich and gnaws gristle behind the Great Wall. Now, in Thubron's eighth decade, the inner action moves to the lines themselves. Where Are You? would have made a better title for this desperately engaging book. The author is addressing his dead mother.

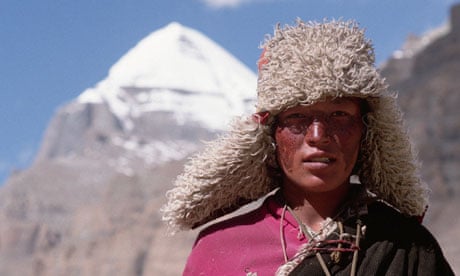

To a Mountain in Tibet tells the simple story of a secular pilgrimage to the sacred slopes of Kailas in the western Himalaya. Travelling on foot with a cook, a guide and a horse man, Thubron sets out from Humla, the remotest of the Nepalese regions. Steering at first by the Karnali river, the group soon swings north-west towards the Nala Kankar Himal that shelves into Tibet, walking under walnut and apricot trees, through silent Thakuri villages and paddy fields, where traders once bartered salt and wool for lowland grains. Thubron conjures the wobble of a tin bridge over a torrent, the "cathedral shadow" of spruce and prickly oak and the two-note song of a Himalayan cuckoo over smooth grasslands. Sometimes the four seek refuge on the mud floor of a home, at other times they pitch tents, greeting, round the camp fire, stocky smugglers in bobble hats driving buffalo freighted with Chinese cigarettes.

Monasteries have always been a Thubronian leitmotif – remember the monk in Journey into Cyprus (1974) who watched the young author shaving and asked if he could pick up the World Service on his razor? A great number punctuate this latest journey, furnishing the creaking prayer wheels and fluttering flags indigenous to Tibetan narratives. The country has long held the west in thrall, the very image of an inaccessible otherworld, an exalted sanctuary and a realm of ancient learning. Thubron admits he has absorbed the romance. As an antidote, he tries to unravel the complex beginnings of the mystique and expose the reality of internal Tibetan violence centuries before 1959 and the hateful Chinese invasion. Through the direct speech of interlocutory monks, he is able to explore the shifting pantheon of regional deities – Hindu, Buddhist and shadowy, shamanic figures who waft through the hinterland.

Restraint has always been a hallmark of Thubron's style, in the travel books at least (he also writes novels). He husbands his lyrical expression artfully. It leapt forth unexpectedly, to great effect, in the memorable first line of In Siberia (1999): "The ice-fields are crossed for ever by a man in chains." Now, in this slim book, Thubron allows his emotional range to expand. This journey, he reveals in the opening pages, is a form of mourning for his mother, who has recently died – the last of his living family.

Deploying a poetic blend of travel and memoir, Thubron uses Buddhism to inform reflections on the cycle of life and the meaning of suffering. Or he tries to: often "memories come too hard for quiet thought". ("The journey does not nurture reflection, as I once hoped," he observes elsewhere. "The going is too hard, too steep.") He describes sorting through his mother's papers and possessions: his father's love letters from Anzio, sepia photographs of Dalmatian puppies, a chipped tea cup. The process was, he says, "a monstrous disburdening". After an especially breathless climb in the rarefied air at 11,000ft, hard by the Torea Pass and just before the book's halfway mark, he recalls the moment his mother clutched at the oxygen mask for the last time, equipment lights winking, regulation curtains closing off the bed.

Juniper and birdsong diminish, and the band camps below the 15,000ft Nara Pass defile into Tibet. At half light, a herd of goats canter through, each carrying a saddlebag of salt and capering to the whistles of Humla buccaneers in conical caps. Across the border, all visitors must travel in Landcruisers to Taklakot, once the capital of an independent kingdom. But China Mobile billboards have replaced 60ft silk banners and obliterated the remnants of feudal sorcery. Taklakot is an image of "lunar placelessness" with "the gutted feel of other Chinese frontier places". And the Mandarin-speaking Thubron is in a position to make such judgments. His 1987 Behind the Wall details a 10,000-mile solo voyage across China.

Onwards to Manasarovar, 200 square miles of water at 15,000ft, a full-blown paradise in the sixth-century Puranas and still the holiest of the world's lakes. Here the Buddha's mother purified herself before receiving him into her womb. (Hindus also venerate the lake.) Thubron visits a cave where Yeshe Tsogyal, Tibet's great saint, spent his last week in a sacred trance. The trained authorial eye never fails. In the hermit's cave, Thubron notes a spent noodle carton, peeling Sellotape and a torch without a battery.

Compared with most of his contemporaries, Thubron has, throughout a garlanded career as a grandmaster of the travel game, taken trouble to construct an elusive persona – throwing up a smokescreen, if you like. So this book breaks new ground. "I want to touch hands," he writes, "that I know have gone cold." In the penultimate chapter, he goes further. He summons – briefly – the memory of his only sibling Carol, dead in an Alpine avalanche at 21. One senses that something from the Grindelwald has been incubating inside this writer for half a century.

To mark this new departure, and to signal the undigested immediacy of a deeply personal journey, Thubron uses the present tense ("We come down gently . . ."). It is risky, and a favourite technique of amateurs, but he pulls it off by embedding the action in the context of its historical background. References to "some dream I had forgotten" even suggest efforts to glimpse the churning subconscious – that deep-sea region where motives glide unseen. Searching and not finding is a notion that recurs in the book. "I stare down from the cave, imaging him [a hermit] climbing the cliff towards me, but the shore stretches empty."

One misses the sustained themes of the more substantial volumes – the disparity between political borders and ethnic realities, for example – but many of the author's preoccupations reach maturation in these pages. The youthful faith surrendered, the reverence for "the tang of human difference", the necessary abjuration of sentiment, the doomed pursuit of truth at all costs and a painful joy at the world's wonder. In many ways, all Thubron's books celebrate the terrible, pitiful, beautiful human condition.

Finally, at the climax of both journey and book, the perfect cone of Kailas. "The mountain is swathed in such a dense and changing mystique that it eludes simple portrayal," says Thubron, hedging his bets. Isolated beyond the parapet of the central Himalaya, Kailas permeated early Hindu scriptures as the mystic Mount Meru. Buddhist texts similarly reveal the pagan gods of the mountain converting to Buddhism and dispatching a multitude of flying bodhisattvas – saints who have delayed entry to nirvana to help others – to protect the furthest crags, lighting up the mountain with their compassion.

Around the base, Thubron finds little compassion – just prostitutes and angry Chinese police swinging riot shields and truncheons (Kailas lies in a disputed border region). Thubron makes the ascent, along with hundreds of pilgrims heading to a zone of "charged sanctity" to find peace with their own dead. At the highest monastery, Choku Gompa, he finds "monks nested like swallows in little cells", single butter lamps casting rods of light on to the snow.

During the last thousand feet of a kora (pilgrimage climb), both Hindus and Buddhists pass into ritual death. The breathless ascent will release them to new life. And so the final chapter finds Thubron at 17,000ft, where the coffee goes cold before he drinks it. He is far too wise a writer to go in for pat endings. Are there ever any, in life? "A journey is not a cure," he says. "It brings an illusion, only, of change, and becomes at least a Spartan comfort . . . To ask of a journey, Why? Is to hear only my own silence." To a Mountain in Tibet offers no redemption and no conclusion. Instead, it is an elegy for everything that makes us human. You can't ask more of a book than that, can you?

Sara Wheeler's The Magnetic North: Travels in the Arctic is published by Vintage.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion